The leading consultancy firm McKinsey worked without payment for Emmanuel Macron when he was France's economy minister, even before he had declared himself a candidate for the presidency in 2017, Mediapart can reveal. The company – which was recently criticised in a report from the French Senate examining the lucrative contracts awarded by the current government to consultancy firms, including McKinsey - banked on Macron's political prospects in the hope of being able to increase its work for the French state in the future, according to documents and witness accounts compiled by Mediapart.

This strategy to win influence with a rising star of French politics chiefly involved offering its services pro bono, with no payment or contract, to Emmanuel Macron when he was France's economy minister from 2014 to 2016. At the same time several members of McKinsey's 'public sector' department took part - again for free - in the launch of Macron's political movement En Marche!.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

One deal in particular cemented relations between Emmanuel Macron and representatives from McKinsey's 'public sector' department. At the end of 2015 the economy minister asked the American firm to work on the outlines of his planned Parliamentary legislation called 'NOÉ'. This stood for 'nouvelles opportunités économiques', and the bill aimed to “free up” growth in French companies.

This so-called 'Macron 2' law - which was in the end ditched in 2016 in favour of the labour reform known as the 'loi El Khomri' - was drawn up by a working group based around a team of four consultants from the firm. But though there had been talk about payment for this work, according to Mediapart's information McKinsey in the end decided to do it for free. “The support work was carried out pro bono and not formalised with a contract,” the business unit at the Ministry of the Economy, the Direction Générale des Entreprises (DGE), confirmed to Mediapart. The DGE added that it had not been involved in “overseeing” this work.

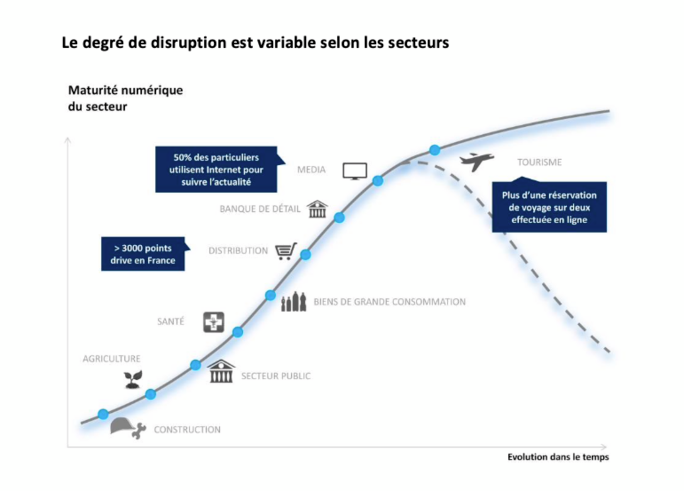

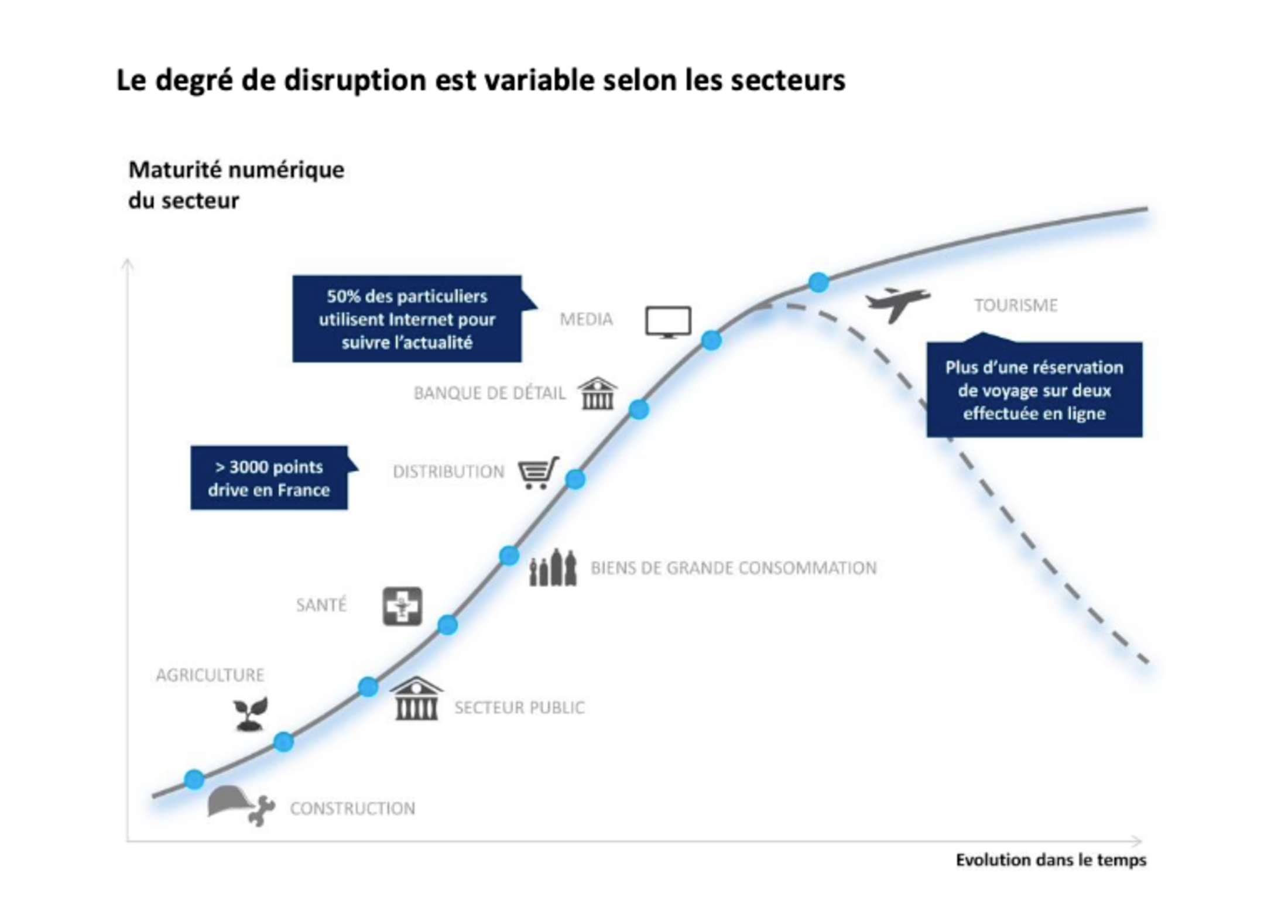

In essence, the McKinsey consultants' task was to assess the economic potential that liberalisation would have on various economic sectors. But the data that was finally presented by the ministry – based on the consultancy firm's work – was not sourced and in some cases was even wrong, as the website Rue89 reported at the time.

This was the case with the presentation of the “degree of disruption” indicator that supposedly showed the “digital maturity” of different sectors in the French economy (farming, health, retail, retail banking, tourism and so on). Yet this indicator was a guesstimate, with the results presented using some fairly unclear graphics, with no scale on the horizontal or vertical axes (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The 'NOÉ' work was brought to McKinsey by its associate director Karim Tadjeddine, whose promotion to head of the 'public sector' unit of the French arm of the American company coincided with the rise of Emmanuel Macron.

The two men had known each other for many years: in particular they had worked together on the Attali commission – a body presided over by economist Jacques Attali to look at ways to boost French growth – which was set up in 2007 and for which McKinsey had already worked pro bono, as several media outlets, including the news weekly L'Obs, reported. A graduate of the prestigious higher education institute the École Polytechnique, Karim Tadjeddine rose up the ranks at McKinsey after the defeat of the Right at the 2012 presidential election.

“Under Nicolas Sarkozy [editor's note, president from 2007 to 2012] executives closely linked to that government rose, but after the election of François Hollande, McKinsey promoted figures such as Karim, who's rather to the left, whatever that might mean when you're working for McKinsey,” recalled a former employee at the firm. “The management adapted depending on the people they were facing,” he added. The result, he said, was that “the institution never loses, it reinvents itself according to political change”.

Karim Tadjeddine had been a member of the 'En temps réel' ('In real time') think tank, which was financed by companies listed on the CAC40, the French stock exchange, and which brought together prominent social democrats, as described by Mediapart's Laurent Mauduit in his book 'Main basse sur l’information' ('The news land grab') published by Don Quichotte in 2016. Emmanuel Macron was also on the organisation's board of directors before leaving when he launched his presidential campaign in 2016.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Despite Tadjeddine's promotion within the company, the initial years after François Hollande's election were not great for McKinsey. “The public sector was flagging,” confirms a former employee. “There were no 'public sector' orders, and in fact Karim Tadjeddine had to find a new role,” added another former colleague. Then the arrival of Emmanuel Macron on the political stage in 2014 gave the firm's public sector activity a new lease of life.

The links forged then grew stronger over time. Two members of the team who worked on project NOÉ, Karim Tadjeddine and Mathieu Maucort, also took part – alongside their work on the bill – in more official meetings at the Ministry of the Economy according to Mediapart's information.

There was a real closeness to Macron, it created quite a community within McKinsey.

These meetings took place from September 2015 onwards, precisely the time when Emmanuel Macron and his inner circle were preparing the launch of his En Marche! movement, which was officially announced a few months later. Mediapart asked the current president and McKinsey for a response and sent them the exact dates of these meetings, but neither commented.

After the public launch of En Marche! and Emmanuel Macron's departure from the Ministry of the Economy in 2016, several members of the McKinsey team went on to work on the official campaign, as shown by several emails that emerged during the MacronLeaks affair and were revealed by Le Monde.

These documents highlight the role played by McKinsey executives, including Karim Tadjeddine, in the public consultation initiative known as the 'Grande Marche' organised by Emmanuel Macron to kick-start the campaign. For example, on September 2nd 2016 Macron's special advisor Ismaël Emelien sent the consultants the “initial elements of the quantitative analysis” of the feedback that activists had obtained going door-to-door.

During the recent Senate investigation into the current government's use of external consultants Karim Tadjeddine explained that their involvement in 2016 had been as volunteers and he regretted that he had used his McKinsey work email account. But was this not simply more pro bono work for Emmanuel Macron, work which was forbidden by the rules governing the financing of public life? McKinsey did not respond to questions on this.

Other McKinsey consultants also took part in actions linked to the running of the campaign, such as brainstorming sessions and the drafting of articles, as the specialist website Consultor revealed in 2019.

“Everyone is free to get involved and participate in a personal capacity and as a volunteer. It's a personal choice which commits only the person who does it. That is true for all the volunteers who helped in the campaign or in the En Marche! venture,” Emmanuel Macron's entourage told Mediapart.

Finally, some McKinsey employees directly joined En Marche! during the campaign itself, such as Mathieu Maucourt, who later became chief of staff to Mounir Mahjoubi, the junior minister in charge of digital affairs. “There was a real closeness to Macron, it created quite a community within McKinsey,” said one former employee.

Among those who switched over in the spring of 2017 was Ariane Komorn, who became the head of the 'engagement unit' at Macron's party, a post she left at the start of 2021 to set up her own business. Étienne Lacourt, who also moved from McKinsey in 2017, came back to work for the consultancy firm having been head of the 'projects unit' at En Marche! for a year.

Another former employee at the firm explained that in addition to the ideological links and the fact that Emmanuel Macron's liberal vision corresponded with that of McKinsey, the arrival of En Marche!, a movement that had no activists or elected politicians, also represented an attractive political opening for some of the firm's staff. Indeed, some members of the consultancy firm had “already tried to get elected but had never succeeded”, recalled the former employee. That was the case of Paul Midy, another graduate of the École Polytechnique, who worked for McKinsey from 2007 to 2014. He had been an unsuccessful candidate for the right-wing UMP – now Les Républicains – at Fontainebleau, south east of Paris, in 2014. He is today the managing director of En Marche!

We sold a fortune's worth of bewildering stuff that was inane.

Yet another former McKinsey employee who moved into Macron's world is Marguerite Cazeneuve, who is now number two at the state health insurance agency the Caisse Primaire d'Assurance Maladie (CPAM) and in charge of Macron's health policies during the current election campaign. After she left the consultancy firm in 2014 Cazeneuve was seen internally as a link between the worlds of Macron and McKinsey and continued to go back her former employer, visiting Karim Tadjeddine's office which was located on a floor usually out of bounds for outsiders. She later worked for Macron's first prime minister, Édouard Philippe.

When questioned on this issue, Marguerite Cazeneuve told Mediapart that she had “gone to McKinsey's new offices a short time after my departure”, in 2015, to “go and see some former colleagues, as is common practice”. She pointed out that she had joined prime minister Édouard Philippe's office six years after she left McKinsey and that since then “none of my duties in public service” had been linked to decisions that made use of consultancy firms.

It's highly problematic when a private consultancy firm takes the place of the state's prerogatives.

Few inside 'the firm' are prepared to discuss these political links. The company remains very discreet about its practices and tries to keep in touch with its former staff. “The vast majority of people go to McKinsey wanting to take full advantage of the network and are thus very careful not to get ostracised by this network once they have left,” said a former partner at the firm.

“At McKinsey there's a very clear internal rule: you don't do politics. But in reality it's very difficult. Because simply having a managerial approach to problems is already political,” said a consultant who left in 2016. Some former staff are even more trenchant in their views and welcome the row caused by the publication of the Senate's report, a controversy that comes just before the first round of voting in the presidential election on April 10th.

“I'm very happy this business is coming out. We sold a fortune's worth of bewildering stuff that was inane,” said one former consultant.

“I draw a distinction between the technical advice and the strategic advice, which commits public policies for years to come. Yet in my experience at McKinsey that's all we did, it's highly problematic when a private consultancy firm takes the place of the state's prerogatives or of democratic debate over the political direction,” added a former female member of staff.

The ex-consultant who is happy that these issue are now being aired also said he was “very shocked to see some projects reaching the level where they define policy”. One of his former colleagues added: “I don't think they're competent to do that.”

These former employees at McKinsey - Mediapart spoke to six in all - also cast doubt over the rigour of the work that was later billed to the state as part of the firm's strategic advice. “The methods employed to collect background information are sometimes staggering, using simple Google searches for example,” said the former female employee quoted earlier. She describes the importance given in McKinsey's services to “deliverables”, which are set out in the firm's well-known PowerPoint presentations at the end of a job (see for example their presentations on vaccinations).

“The 'number one' product at McKinsey is the slide,” she said. “They're produced in India while it's nighttime in France. You send all the information in the evening, and the following morning they're sent to you.” This system enables the firm to respond very quickly in its work.

Across the world McKinsey has developed a culture of joint ventures, allowing it to develop synergies of great efficiency. “In each office on the planet you have people of a very high level with identical working methods, it's very impressive,” adds one former consultant.

“You can carrying out benchmarking in very little time, sometimes just hours, it's a firepower that the state itself doesn't possess,” he added. Out of this culture springs the notion that “everything you touch turns to gold”, he said. “You think that you can get a Swiss consultant to come and get involved in public accounting in France without a problem,” he said.

“How can you move so quickly? It's by foreseeing the responses to the questions that you ask,” said the former partner already quoted, who is also critical of the methodology that has been developed inside the firm. “A major working principle is that the a priori [editor's note, that which is self-evident] is more important than researching a solution,” he said. “We're used to reasoning through the thesis-antithesis-synthesis approach. At McKinsey it's hypothesis-verification-communication. The right presentation is very important, the aim is that they can't say no to you. If the presentation is well put together it's very hard for the client to say that they don't agree with the conclusions.”

Scandals around the world

Among the former consultants spoken to by Mediapart, several also talked about problems of an ethical nature, and quoted the scandals that have tarnished their former employer in different parts of the world. McKinsey was founded in the United States in 1926, but is now based in 65 countries.

“Amid all the stuff that's coming out in the French media there's something missing and that's the international dimension,” said the former partner. Yet, he said, this is the “same company, with the same ethics: you take what comes and you don't pay attention to what's being done. You take the money, without having doubts.” He said this approach is reinforced by the way the business is structured as a partnership – the top managers are partners - by its “up or out” culture, and by the absence of internal constraints.

Last year McKinsey agreed to pay 573 million dollars to settle claims with 47 American states who alleged it shared some responsibility for the country's opioid epidemic which over two decades led to up to 450,000 overdose deaths. The states accused McKinsey of having supplied marketing advice to drug manufacturer Purdue Pharma LP in order to boost their sales, notably of the Oxycontin painkiller. Under the terms of the settlement, however, McKinsey did not accept responsibility for any wrongdoing.

In 2018 the prestigious consultancy firm was also under investigation in an alleged corruption scandal in South Africa. A parliamentary inquiry there determined that the partnership it had concluded with the company Trillian – who are accused of the misappropriation of funds from the country's public energy producer – could constitute criminal conduct. McKinsey repaid around 72 million dollars in fees over the scandal.

In the same year the consultancy also came under criticism for having worked for several authoritarian regimes, including China. A controversy broke out after The New York Times revealed that the firm held a corporate retreat just four miles from Kashgar where the Chinese authorities have an internment camp in which several thousand Muslims from the Uyghur ethnic minority group were locked up.

Another grey area is in the pro bono services that the company provides and the gaining of influence that is inherent in this. In its recent report into consultancy contracts the French Senate's committee of inquiry looked into this phenomenon, one which had moved away from its original aim of helping the public good.

First of all the senators highlighted how the absence of a contract “constitutes a major difficulty, in particular because it doesn't allow the state administration to impose any ethical obligations on its service providers”.

The Senate report also said that free work could be “used” for the “requirements of the consultancy practices' commercial strategy”. It talks of a “foot in the door” approach to describe this entryism strategy. When he appeared before the committee the sociologist Frédéric Pierru told senators that pro bono work was part of a “desire to maintain a brand image [for the firms], so they can continue their business afterwards”.

A campaign team is made up of volunteers, consultants and also students and retired people.

In its report the Senate uses the example of the 'Tech for Good' summit organised by the Élysée in 2018 and on which McKinsey worked for free. The consultancy firm then made use of this involvement for its October 3rd 2018 bid to work on a framework agreement for the Union des Groupements d'Achats Publics (UGAP), which handles state central purchasing. McKinsey stated in its bid that it had been in a position to invite “UGAP senior management to big events in which [it was a partner]”. In particular it cited the “Tech for Good seminar organised with the presidency”. The Senate report observed: “It's gone full circle.”

Finally, the Senate report took the view that pro bono work may carry the risk of a costly quid pro quo, and it quoted the fears expressed to them by senior public servant Martin Hirsch. “There is a risk that [for a consultancy firm] a pro bono commitment can be a way to make itself indispensable,” said Hirsch, who is the managing director of the large Paris region health authority AP-HP.

Taking into account the “major” ethical risks involved, the Senate's committee of inquiry therefore recommended simply banning outright any pro bono services being provided for the state.

The government subsequently picked up on this proposal during a press conference given by the minister for the civil service, Amélie de Montchalin, and public accounts minister Olivier Dussopt. Anxious to defuse the affair, which has broken in the middle of the election campaign, the ministers announced that from now on pro bono services offered to the state would be limited to “exceptional situations”.

Addressing the links between McKinsey and the 2017 Macron campaign, Amélie de Montchalin said that “a campaign team is always and everywhere made up of volunteers and consultants, and also students and retired people. They get involved because they have personal convictions.” This did not support the “allegations of cronyism”, she said.

“While the government insists it has 'nothing to hide', it has taken five years for it to react, while spending on [consultancy] advice for the state more than doubled between 2018 and 2021,” responded Arnaud Bazin, from the right-wing Les Républicains, who is president of the committee of inquiry, and communist senator Éliane Assassi, the inquiry's rapporteur.

In its press statement the Senate also declared that it “duly noted” the organisation of this “communications operation” at the “offices of the Ministry of the Economy and Finances” some “ten days from the first round of the presidential election” .

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter