The trial opened on Wednesday of 14 people accused of acting as accomplices to three separate terrorist attacks in Paris that began on January 7th 2015 with the shooting massacre at the offices of the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, before the killing of a policewoman, and the murders of hostages at a kosher store, claiming a total of 17 lives, and ending with the deaths of the three perpetrators.

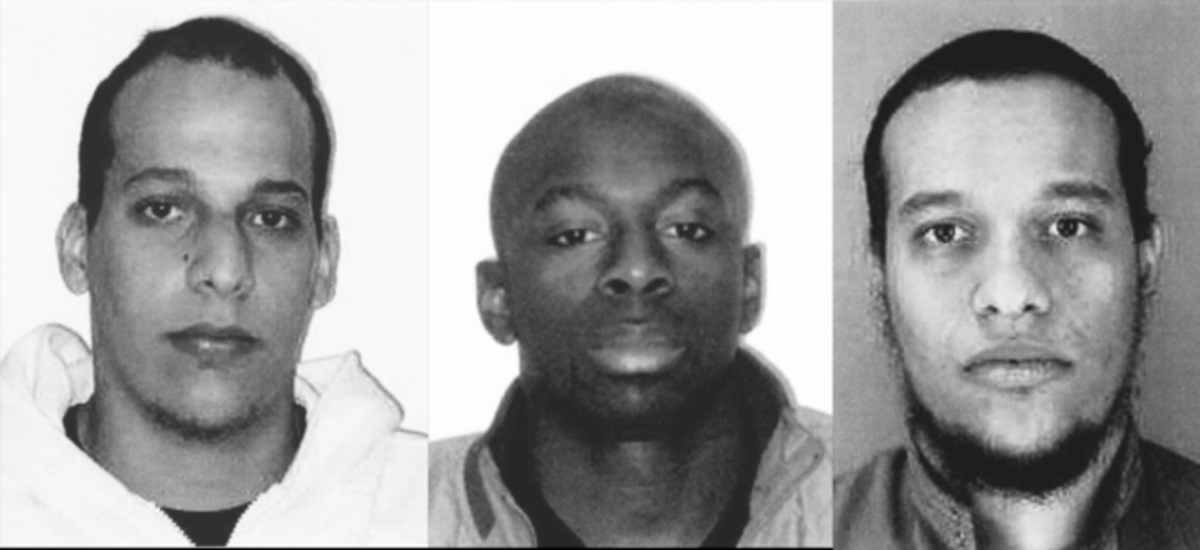

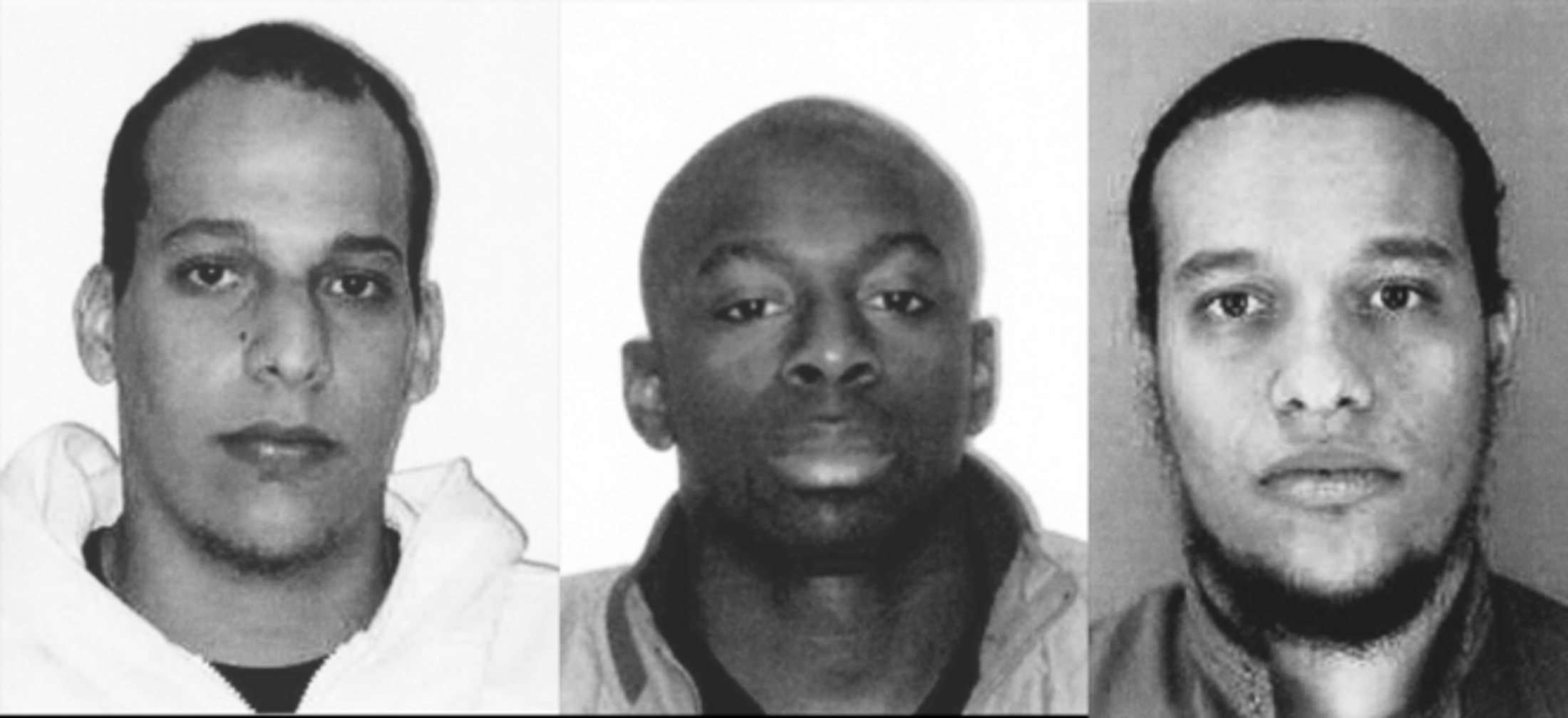

While it can be hoped that during the hearings at the Paris law courts, due to last until November 10th, new evidence will emerge to fill in some of the blanks in the puzzle of events surrounding the attacks, it is also probable that it will prove in parts frustrating for the some 200 civil parties to the trial, beginning with the absence of the perpetrators themselves – the brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, who killed 12 people in and around the offices of Charlie Hebdo, including some of France’s most celebrated cartoonists, and Amedy Coulibaly, who shot a policewoman dead before murdering four people during a siege of the Hyper Casher store on the outskirts of south-east Paris.

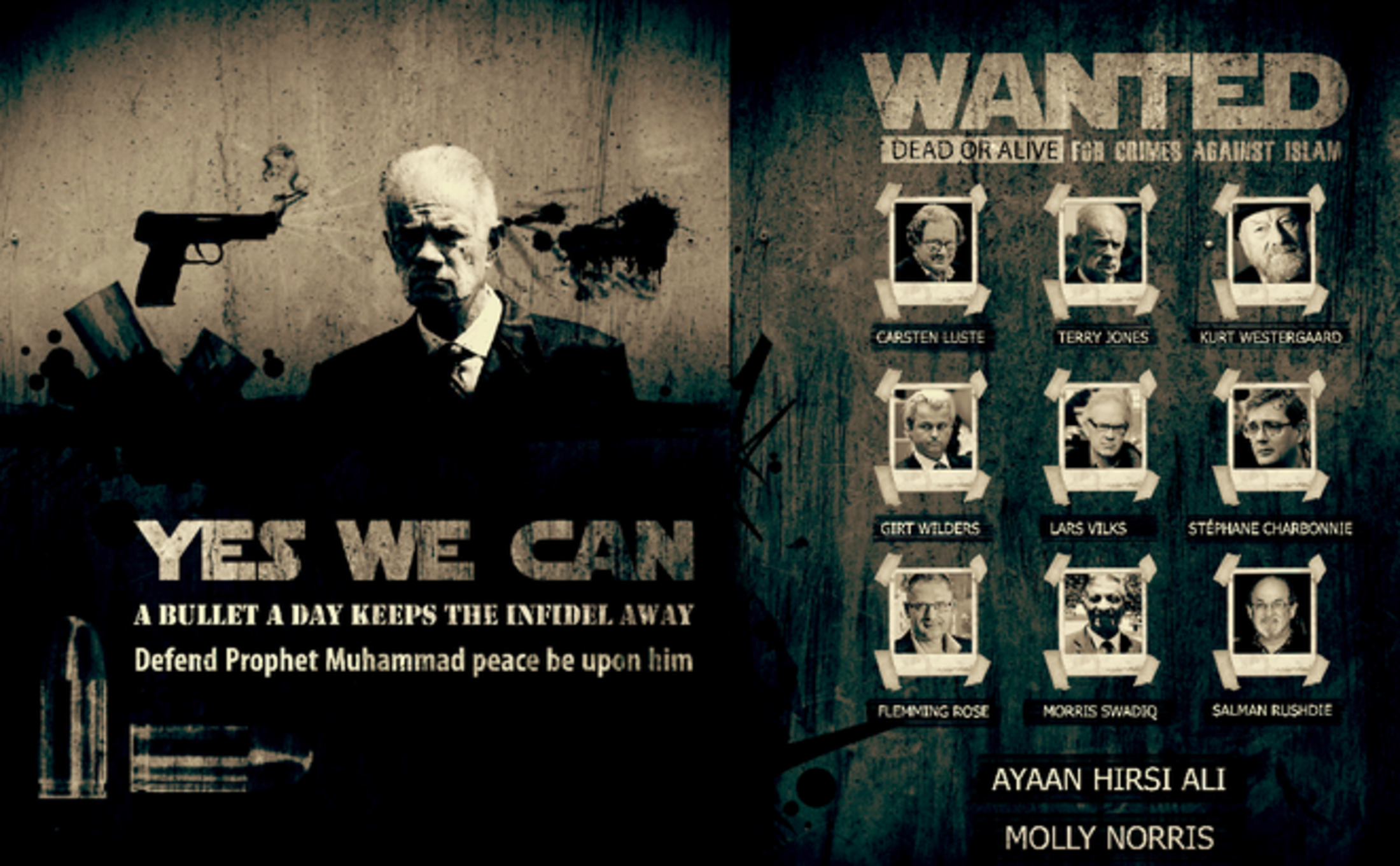

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The three died within 20 minutes and 40 kilometres of each other on the late afternoon of Friday January 9th 2015 – the Kouachi brothers at a printer’s office north of Paris where they had barricaded themselves, shot down by police as they ran out firing their weapons, and Coulibaly inside the kosher store after police stormed the building. Their suicidal end is a hallmark of jihadist terrorists, mirroring a series of attacks in France which, beginning with the Charlie Hebdo attack, have left 270 people dead and more than 800 wounded and injured, and which will also be the subject of other trials in the months to come.

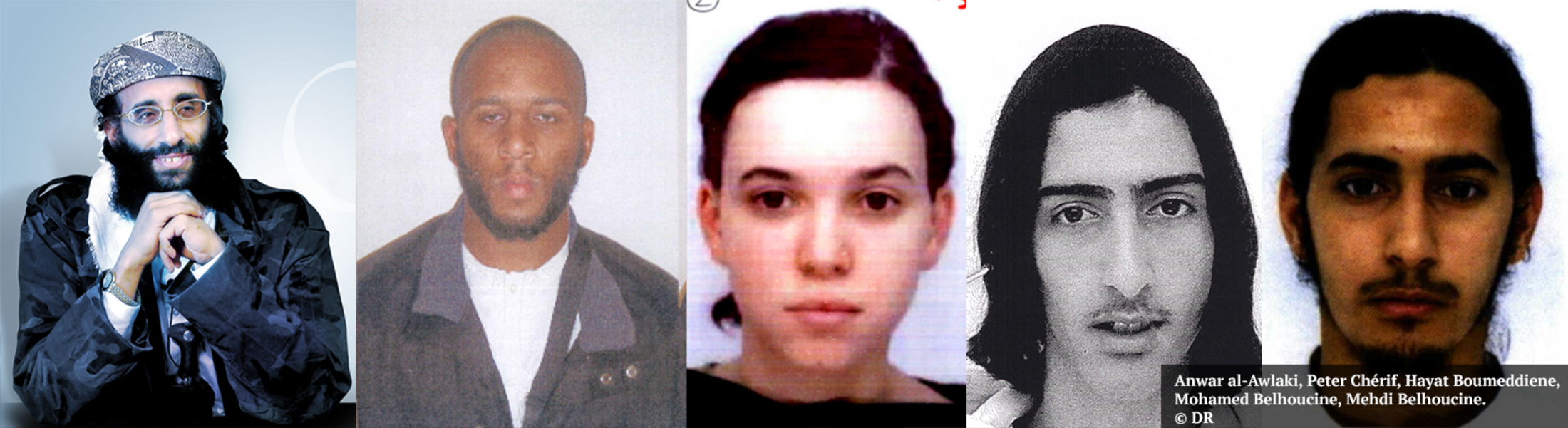

But there is also likely to be frustration for the relatives, friends and colleagues of the victims of the murderous events in January 2015 because of the absence of others from the dock, notably three among the 14 accused – Coulibaly’s companion Hayat Boumedienne, who he married in a religious ceremony, and brothers Mohamed and Mehdi Belhoucine – all of whom may be either dead or still circulating in Syria. There is also the case of Peter Cherif, suspected of involvement in organising the Charlie Hebdo attack and mentoring the Kouachi brothers but who, for technical reasons, escaped charges and who will be questioned by the court as a simple witness via a video link from the French prison where he is being held.

Those facing the most serious charges of complicity in the attacks, and which carry a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, are Ali Riza Polat, a French national of Kurdish origin, and the absent Mohamed Belhoucine.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The remainder are mostly made up of associates of Coulibaly, who are accused of securing for him weapons and equipment, including tactical body armour vests, knives, a Taser stun gun, teargas canisters and gloves. DNA traces from two of these defendants, who face up to 20 years in prison if found guilty, were found on the equipment Couibaly had with him in the kosher store.

Under questioning by investigators, one of them denied knowing of Coulibaly’s terrorist intentions but believed he wanted the vest “to commit a holdup of something by passing himself off as a police officer”. Another, a childhood friend of the killer, said he thought the equipment he passed on was for use in a drugs run with a “go fast” car, or to hold up a “go fast” drugs run. Their defence will be that Coulibaly’s serious criminal background made this plausible.

In the document detailing their arguments for sending the defendants for trial, the examining magistrates who led the investigations wrote that their complicity “does not demand precise knowledge of the project” of the perpetrators, and that it was “not at all necessary […] to share the radical ideology of the perpetrator of the events”. In the case of a childhood friend of Coulibaly, who some have described as being something of a whipping boy for the latter, the magistrates justified the charges against him on the basis that, “he could not have ignored” Coulibaly’s “capacity to commit acts linked to his jihadist ideology”.

Ali Riza Polat, who has a history of small-time drugs dealing, is the only one of those present in the box who is charged with “complicity in all the terrorist acts” carried out by Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers. He is notably accused of putting Coulibaly in touch with an arms dealer in Belgium, and that he helped bring weapons into France in August 2014. Amongst the evidence held against him is a note drawn up in his own handwriting in which he asked about the price of explosives, detonators and munitions, including cartridges for Kalashnikov automatic rifles. Phone records establish also that, as is the case of some other defendants, Polat met with Coulibaly in the days leading up to the January 2015 attacks.

Three days after the massacre of four men hostages at the Hyper Cacher store, Polat left France for Lebanon, from where he attempted to reach Syria. But a few weeks later, when the first arrests in connection with the January 7th-9th attacks were made, he travelled to Thailand. Under questioning, Polat has denied supplying or selling arms to Coulibaly or the Kouachi brothers, and claimed that if he knew of their terrorist plans he would have left France before the attacks.

The evidence in the prosecution case against the 14 now standing trial, and which is detailed in 171 volumes of files, is far from circumstantial, including DNA evidence, phone taps, records and geolocation, and witness statements.

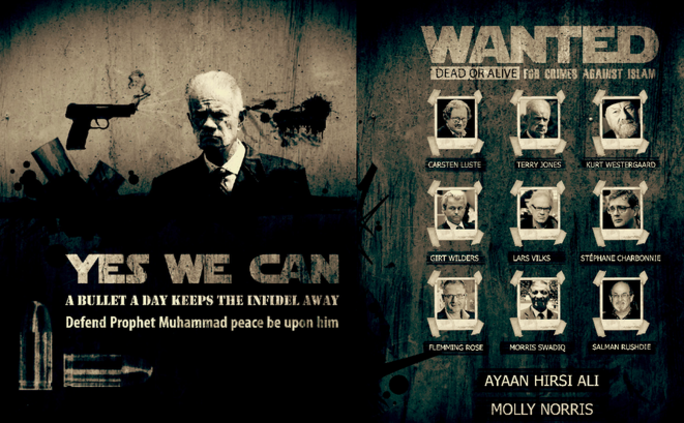

But the difficulty resides in the very nature of the crimes that took place; a series of attacks, prepared over a long period of time and committed by three men who knew and mutually helped each other in their macabre projects, which were separately carried out for two rival terrorist organisations. Amedy Coulibaly claimed allegiance to the so-called Islamic State group, while the Kouachi brothers claimed their massacre of 12 people in and around the Charlie Hebdo offices in the name of al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

“During the investigation […] numerous people in the environment of the perpetrators or in connection with elements of the inquiries were placed in custody, without the investigations allowing to demonstrate that they participated in any form in the preparation of events,” wrote the examining magistrates.

A prime example of the difficulties is the case of the man who commanded the Charlie Hebdo massacre, Anwar al-Awlaki. During their siege inside the printers at Dammartin-en-Goële, north-east of Paris, hours before they were gunned down by police, a journalist from rolling TV news channel BFMTV succeeded in placing a phone call into the building, answered by Chérif Kouachi who gave a brief interview. “I was, me, Chérif Kouachi, sent by al-Quaeda in Yemen,” he declared. “It is Sheik Anwar al-Awlaki who financed me.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Born in the US to Yemeni parents, al-Awlaki, an Islamist preacher, was responsible for foreign operations carried out by AQAP. In a video published on the internet on January 14th 2015, Yemen-based AQAP claimed responsibility for the Charlie Hebdo massacre and confirmed that al-Awlaki was responsible for its “implementation”.

While it is not contested that al-Awlaki commanded the attack, he was in fact killed by a US drone strike four years earlier, on September 30th 2011. That was just a few weeks after Chérif Kouachi arrived in Yemen, via Oman (apparently travelling on his brother Saïd’s passport).

The investigation leading to the trial that opened on Wednesday sought to identify the person who may have facilitated the Kouachi brothers’ integration into the ranks of AQAP, and identified as the likely suspect a French man called Peter Cherif, a childhood friend of the brothers, having grown up in the same Buttes-Chaumont district of Paris as them. Cherif left France to fight against the US forces present in Iraq after the 2003 invasion of the country.

He was captured near the Iraqi city of Fallujah by US-led coalition forces at the end of 2004, and handed over to the Iraqi authorities who in 2006 sentenced him to 15 years in jail. He escaped in March 2007, along with around 150 other inmates, after rebels attacked Badush prison, north-west of the city of Mosul, where he was being held. Re-arrested in Syria, he was extradited to France where he spent 17 months in preventive detention before he was bailed ahead of his trial. That was when he fled France and reached Yemen.

On September 10th 2011, US intelligence informed their French colleagues that a person had been in communication with Cherif, alreadey by then in Yemen, from a cybercafé in the Paris western suburb of Gennevilliers. The cybercafé was situated on the same street as where the Kouachi brothers had been living for the previous three years.

On August 3rd 2013, according to a document drawn up by the French domestic intelligence agency, the DGSI, after the January 2015 attacks, US intelligence “partners” informed the agency of an “imminent threat” of an AQAP plan to launch a terrorist attack against “French or American interests”, and which “would potentially implicate” Peter Cherif.

Cherif was finally tracked down and arrested in December 2018 in Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa, which lies opposite Yemen across the Gulf of Aden. He was swiftly extradited to France and jailed. On August 20th this year, French weekly news magazine L’Express cited from statements given to the DGSI by Cherif after his arrest. According to these, he confirmed he was a recruiter for AQAP of foreign jihadists for operations abroad, and had been acting under the orders of al-Awlaki. He also reportedly admitted providing accommodation in Yemen for Chérif Kouachi (as well as Salim Benghalem, a French jihadist who was to become a notorious member of the Islamic State group and who died in Syria in 2017).

But the questioning of Peter Cherif’s occurred several weeks after the French examining magistrates, in January 2019, had wound up their investigations into the January 2015 attacks. They had already proceeded with the final formalities of notifying this to the civil parties to the case and the accused, after which the prosecution services sent the 14 defendants for trial. Cherif, therefore, was not among them. He has since, however, been placed under investigation for “associating with terrorists” in a case separate from the current trial, and he is, at present, legally not implicated in them.

In the trial which opened on Wednesday, the 38-year-old will be questioned as a witness only, when he is due to appear at the end of September via a video link from his prison.

-------------------------

- The second of this two-part report will be published on Thursday.

English version by Graham Tearse