Welfare benefit fraud is currently a regular headline topic in the French media, and the ruling UMP conservative right party has made it a campaign issue for next year's presidential and legislative elections. But are France's welfare-dependent, dismissevely described as 'les assistés', really Europe's champion scroungers, as some pretend? Mathieu Magnaudeix argues here, figures in hand, why the issue is a political smokescreen that ignores both the facts and the massive cost of tax fraud and evasion by the well-off.

-------------------------

France's political parties now have their sights set on next year's major electoral battles - the presidential and legislative elections, to be held in the spring and early summer. Kicking off for the conservative right ruling party, the UMP, Patrick Buisson, a highly influential advisor to French President Nicolas Sarkozy, laid out, in French weekly magazine Paris-Match, a "battle plan" aimed at retrieving electoral ground from the far-right National Front (FN) party in time for 2012.

The UMP, and notably Sarkozy if he runs as expected for a second term in office, is threatened by the revival in popularity of the FN, demonstrated in March local elections and regular opinion poll surveys. High on Buisson's agenda were issues of immigration, national identity and the fight against a so-called mass of welfare scroungers.

These issues are dealt with within the framework of a major bill to rehabilitate the work ethic. While four million people are unemployed and the economic crisis continues, Buisson proposed "reserving the RSA [Editor's note: Revenue de solidarité active, a subsistence welfare benefit awarded to the most disadvantaged]to beneficiaries who have a job". But among the 1.8 million beneficiaries of the RSA, only 650,0meet this requirement. If such a bill were passed, more than a million people, and their families, would thus be deprived of resources.

Denouncing welfare dependence, an issue bound to mark a sharp division between the right from the left, has become a mantra of the hard-line conservative fringe of the UMP. Late March, Pierre Lang, Member of Parliament for the Moselle, in eastern France, proposed forcing the unemployed to perform community service work. Several days later, the Secretary of State for European Affairs, Laurent Wauquiez, announced in French daily Le Figaro, a proposed bill linking the RSA to a conditional unpaid "five hours of general interest work" per week. "It isn't a sanction but a step towards employment," he said in the interview.

Reacting to the proposal, Martin Hirsch, the former government High Commissioner for Active Solidarity Against Poverty (2007-2010) who created the RSA denounced "demagogic proposals, dangerous because inefficient" which "begin to flower in this pre-electoral spring".

In recent weeks, the Ministers of Solidarity, Roselyne Bachelot, and of Health and Labour, Xavier Bertrand, have repeatedly commented on the issue of welfare fraud, a popular theme with the conservative electorate. Even François Bayrou, leader of the moderate centre-right Modem party, has said that the Socialist Party (PS) 2012 election manifesto is a programme that will encourage "welfare dependency".

On April 13th, a group of some 40 MPs from the UMP proposed a text for legislation that would limit eligibility to a subsistence benefit for senior citizens (in French, minimum viellesse) currently paid out to about 700,000 people aged over 65 living on incomes of less than 9,000 euros per year, regardless of nationality. The MPs demanded that beneficiaries must be either French nationals or people who have worked in France.

In a letter obtained by Mediapart ,the chair of the state-run pension fund (Caisse d'assurance-viellesse), Danièle Karniewicz, responded to the MPs with a reminder that "for people who have never worked in France, the [benefit] does not represent a pension but a minimum of subsistence," she said.

Nicolas Duvoux, sociologist at the University of Paris, centred on the issue of ‘the welfare-dependent' in his book (left) L'Autonomie des assistés (‘The autonomy of the assisted'). He uses the term to challenge conventional wisdom which holds that welfare beneficiaries wallow in poverty, apathy and idleness. Duvoux believes that the welfare-dependent, the so-called ‘assisted', "are those who are poor, who need to be helped".

According to French national statistics institute INSEE, eight million people in France live in poverty with an income of less than 880 euros per month. But for many French people, the word ‘assisted' is of course derogatory. "The term conjures up people who are dependent on the state, as if the social safety net were a cover for moral decay," explained Duvoux. It also conjures up a series of stereotypes: poor people (like the gypsy travellers) who drive expensive BMW cars (a notion encouraged by President Sarkozy, as reported here) , or of days spent playing computer games rather than seeking work, of so-called ‘zip-opener benefits' (allocations-braguette) based on the theory that the poor, often foreigners, have childrenin order to benefit from family allowances.

"These representations appeared in the late 1970s in the United States," said Hélène Périvier, an economist at left-leaning economic think-tank OFCE. "Republican Ronald Reagan [US president 1981-1989] peppered his speeches on social issues with references to the ‘welfare queen'".

The ‘queen' was supposedly a destitute woman in a Chicago ghetto who allegedly drove a Cadillac, loved champagne and is said to have defrauded $150,000 from various welfare offices by inventing 80 names, 30 addresses and four dead husbands. In fact, this person never existed, as proven by US journalist David Zucchino in his book, Myth of the Welfare Queen (pictured right).

In the collective sub-conscious of White America, the ‘welfare queen' is often Black. "Welfare programmes are designed to help the poorest and the poorest are generally dominated populations - women or ethnic minorities," said Périvier of the OFCE.

The stereotype of the idle and fraudulent poor has flourished in Europe also, where, since the mid-1990s, it has been used by numerous politicians, both on the right and the left.

"Mentioning the ‘assisted' in political debate is to make use of a coded language," explained sociologist Nicolas Duvoux. "The term often evokes, without need to name them, foreigners," he said. Indeed, French presidential advisor Patrick Buisson puts the fight against welfare dependency on the same level as questions of immigration or national identity.

However, those that rail against the welfare dependent are hardly all racists. "More and more people, especially from the lower middle class, as well as young people, feel cheated out of the [welfare] solidarity system," explained Danièle Karniewicz, the chair of the French national Pension Fund. This, according to sociologist Olivier Schwartz, especially affects a whole swathe of the French lower middle class engulfed by the "growth of social disadvantage". These include workers earning the minimum wage or just above, the young, or those with eroding low-revenues, who have the feeling they are paying for everybody, for the rich but also for the more disadvantaged who benefit from welfare payments.

Nicolas Duvoux argues in his book that beneficiaries of the RSA refuse the term welfare for themselves but will use it without compunction to describe others.

France's social safety net comes at considerable cost. Solidarity is expensive. According to the Ministry of Health, France's national Social Security1 system, la Sécurité sociale, which will post a deficit of 24 billion euros in 2011, each year pays out 600 billion euros in benefits that include health, pensions, family allowances and the RSA.

This represents 31% of the gross domestic product (GDP), one of the highest percentage rates among OECD member nations, whose 34 members are the richest on the planet, and almost twice as much as in the US. The safety net is significant and has helped France to weather the crisis better than many of its neighbours.

The cost, however, rises by at least 4% per year - and rose by 4.7% in 2009 because of the economic crisis - which is twice as fast as GDP.

"Among all European countries, France is the most generous in terms of social welfare payments which have increased 50% in ten years," claims IFRAP, a French think tank focussed on public sector spending and policy and which advocates decreased public spending, in its presentation of a report on welfare spending sub-titled "the uncontrollable skid". Yet, subsistence benefits are but a small part of all French Social Security system spending. About 80% of the total, or 480 billion euros, is dedicated to pension and health payments from which everybody benefits.

Ministry of Health figures show that 3.5 million people receive one of eleven means-tested benefits. Including family members, such as children and spouses, six million people receive some form of benefit. Not all are out of work. For one third of the 1.8 million homes receiving the RSA, at least one person is employed - which is the basic idea behind the RSA, providing income support to encourage finding a job.

The number of beneficiaries of subsistence benefits has not skyrocketed. As seen in the graphic below, it is mostly dependent on the economic situation. The number of RSA recipients rose by 14% between late 2007 and the end of 2010.

Graph above (in French only) shows 1999-2009 evolution of principal minimum welfare subsistence benefits (source: French ministry of Work, Employment and Health).

The unquestioned success of the RSA is also due, according to Nicolas Duvoux, to the increasingly restrictive access to unemployment benefits negotiated between trade unions and successive governments, on both the left and the right, since the 1990s. "Between 2001 and 2005, beneficiaries of the RMI [Revenue minimum d'insertion, replaced by the RSA in 2009] rose by 30 %," he said. It acts as an emergency back-up to France's social safety net when it was originally designed as a first step towards finding employment.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, subsistence benefits in France are low. While the minimum monthly working wage is set at a gross 1,365 euros per month, the base RSA payment is a monthly 467 euros for one person and 980 euros for a couple with two children. This represents barely half of the poverty level http://www.inegalites.fr/spip.php?article343&id_mot=76 for monthly incomes.

"Compared to the median income [half earn more than the median, the other half less], the RMI has lost 34 % since the beginning of the 1990s," he noted. The same relationship also holds with minimum wage, which, at least, is indexed to inflation.

According to a 2007 study of France and 11 European countries by the French Institute for Economic and Social Research (IRES), the amounts of the subsistence benefits guaranteed to poor people were "much higher" in the 11 other countries. The gap, it reported, was higher "by 30 to 40% in the United Kingdom and in Finland, by 50 to 75% in Ireland, Sweden, Belgium and Holland, by about double in Norway and in Iceland, by about double for couples and 140% for single parents in Austria, and by about 150% in Denmark".

"By making the weak more destitute, France is cultivating a noxious exception within Europe," argued Olivier Ferrand, president and founder of left-wing think tank Terra Nova and an influential member of the Socialist Party. He called for an increase in subsistence benefits, "because the quasi-majority of those under 25 are also excluded from the RSA, an exception in Europe," he said. The amount of subsistence benefits, he added, was building "a generational hierarchy in our country" by paying "709 euros as the minimum [monthly] pension, 460 euros for the RSA and zero for the young."

For many social protection experts, the significant number of subsistence benefits proves most of all that the French social model is wearing out. In this system, designed after WWII, at the dawn of 30 years of booming economic growth [called les Trente glorieuses], everybody was accorded social protection based on rights acquired through employment and family. "Social Security is not based on citizenship but on the need to protect the French worker, his wife and his family," commented sociologist Nicolas Duvoux.

With industrial decline, job insecurity, unemployment and the breakdown of traditional family structures, the system creates an increasing number of excluded people - notably among the young and single mothers - who depend on subsistence benefits. "France still deals with poverty according to the social status of the person, not according to their needs," said Duvoux.

On one hand there is a world protected by the safety net - benefits for unemployment, pension, health - regulated by trade unions and employers. In this system a job-seeking, executive-level employee benefits from the highest unemployment compensation ceiling in Europe (up to 5,700 euros per month). On the other hand, there is a world of welfare left to local communities, where subsistence benefits are very low and fail to provide for a financial and social rebound. "The social protection structures and social structures are diverging more and more. Welfare doesn't fight the causes, it just mitigates the effects," Duvoux said.

-------------------------

1: La Sécurité sociale (Social Security), commonly called 'la sécu', usually refers to the state system managing health care benefits. But it also includes an array of benefits including pensions and family allowances. Family allowances are available equally to all families, regardless of income, based on the number of dependent children.

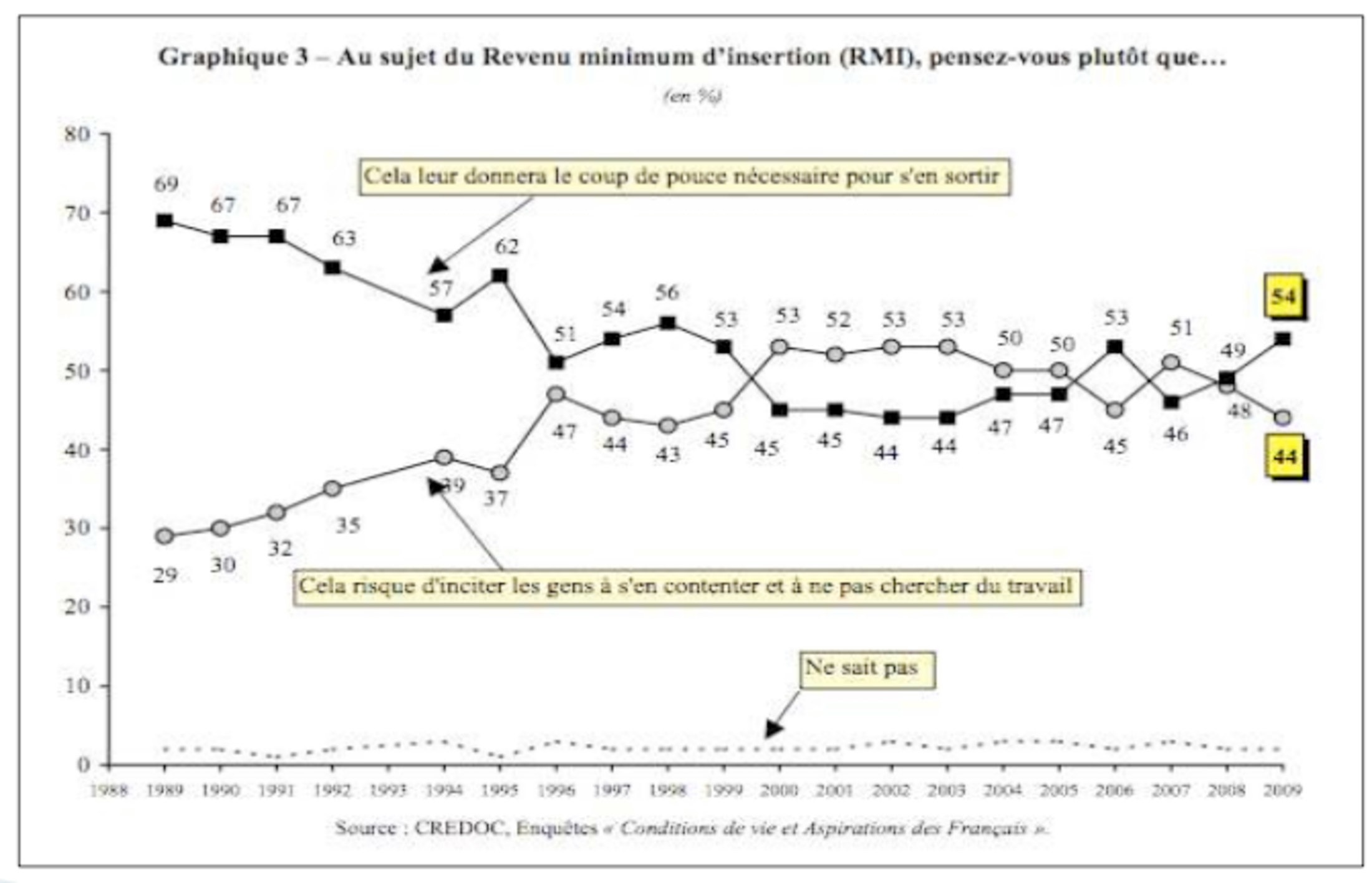

In a study of opinion polls between 1989 and 2009 (see below) by the French Research Centre for the Study and Monitoring of Living Standards, the Credoc, public opinion in the country has increasingly moved towards the belief that receiving a subsistence benefit such as the RSA encourages idleness (54% claimed this in 2009 against 29% in 1989).

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Graph above (click to enlarge) shows 1989 - 2009 evolution of polled public agreement with one or other of the following statements: ‘Minimum subsistence benefit (RMI) gives people a necessary boost to get by' - (top of graph) - and ‘Minimum subsistence benefit (RMI) can incite people to stay put and not look for work'.

Yet, other than one study by French national statistics institute INSEE which met with criticism over its methodology, there is no proof of that assertion. A 2009 study by the French Public Treasury Office of 7,000 beneficiaries of either the RMI, single parent benefit, and the ASS (Allocation spécifique de solidarité, aimed at free-lance workers and long-term unemployed) found that only 4% of those polled said a loss of benefit income was the reason they had not found work. According to France's National Office for Family Allowances (CNAF), only 1% of beneficiaries refuse a job because of financial loss.

The studies agree that even if the financial gain is minimal, beneficiaries of subsistence benefits generally prefer to take a job, and they often will take a job even if they incur a financial loss. The primary motivation for refusing work is not monetary.

In an article in French daily Le Monde, the former High Commissioner for Active Solidarity Against Poverty and who created the RSA, argued that the idea that beneficiaries of subsistence benefits wallow in idleness is all the more erroneous because "beneficiaries of the RSA are required, barring serious health problems, to seek a job and to be signed up at the [State Job Centre]" and thus "must comply with the requirement to accept two reasonable job offers".

A study by the Ministry of Finance showed that if one fourth of RMI beneficiaries didn't seek employment, it was primarily for reasons of poor health or personal constraints including the feeling of being unemployable due to a long period out of work, lack of a vehicle or child-minding issues.

The great majority of the beneficiaries of the RSA see their situation as a "stigma," said Nicolas Duvoux. Indeed, one million eligible low-wage earners don not even request it. The fault also lies with the very personal nature of the questionnaire required to obtain the benefit, Duvoux added.

Rather than blaming the alleged laziness of beneficiaries of subsistence benefits, others blame the sluggish state of the job market, the sad state of professional training; the poor support provided to the unemployed added to the crisis at the national employment centres1 (Pôles emploi), or the institutional maze intrinsic to the system. For example, training depends on local authorities, the RSA being delivered at the county (département) level while unemployment benefits are obtained from the national Employment centres.

Terra Nova's Oliver Ferrand said the Socialist Party manifesto for the 2012 presidential and legislative elections would propose introducing "a professional social security system with personalised monitoring and adapted training" and that "a contract would be made with the job seeker with a logic of rights and duties," he added. It remains to be seen, given the cost, whether such a measure garner the support needed to pass in the legislature.

-------------------------

1: In January 2009 the Job Centre (ANPE) and the Unemployment Benefits Office (Assedic) were merged into a single entity (Pôle Emploi). Badly organised, the merger disorganised a system already overloaded by the economic crisis causing delays in both benefit payments and in filling available positions.

Welfare fraud is a subject never far from the covers of the French weeklies. A recent issue of Le Point headlined 'Those that are ruining France" (photo left), in an article denouncing "healthcare crooks".

The stories mostly centre on unemployment benefit fraud, of subsistence benefit fraud, of healthcare benefit fraud, sometimes on an organised scale. There are several per month. When, in the midst of last year's debate on wearing the burqa in public, then- interior minister, Brice Hortefeux himself denounced the case of Lies Hebbadj who, according to daily Le Figaro, had four wives, 17 children and had accumulated 175,000 euros in benefits over three years, it was bound to make the top story.

Several MPs of the ruling conservative UMP party announced in early March that they were proposing a bill that would allow RSA beneficiaries to be monitored without warning and would require the creation of "a social pass on which all benefits received by the card-holder would be listed".

Obviously welfare fraud does exist. Jean-Pierre Door, UMP MP for the Loiret, in north-central France, evaluates it at 15 billion euros. But this is just a guess; no-one knows the real cost.

At the national Office for Family Allowances, which distributes 60 billion euros annually, fraud is evaluated at between 540 million euros and 808 million euros per year, 88% of which is recovered over three years. In the Pension Plan, fraud is estimated at 25 million euros per year, not counting organised scams which are more costly, especially over long careers. The French national audit office (la Cour des comptes) estimates the Job Centre reorganisation fiasco cost 2 million euros. But the fraud figures are probably underestimated according to a 2008 report by the Council for Strategic Analysis which advises the Prime Minister. "We should create a welfare benefits police, to stop the actions of the small minority that abuse the system," suggested Olivier Ferrand.

But welfare recipients are not the only ones to engage in defrauding the state. MP Jean-Pierre Door admits that most of the health care fraud is due to "unnecessary medical care". A high-ranking official at the Ministry of Finance noted that "the government tends to focus on benefits, but there are enormous stakes, and perhaps even greater health benefit fraud perpetrated by doctors, hospitals or [private] clinics," all of which are part of the conservative right's traditional electorate.

The national audit office estimates tax and welfare fraud totals, at least , between 29 billion and 40 billion euros annually. That represents between 1.7% and 2.3 % of annual GDP. Undeclared work, or moonlighting, costs the State between 6 billion and 12 billion euros per year in lost income from employer and employee contributions.

But what costs public finances most is tax fraud. This is estimated at 4.3 billion concerning lost income tax, 4.6 billion concerning lost corporate tax and between 7.3 billion and 12.4 billion in lost Value Added Tax. That does not include the numerous loopholes and legal tricks for avoiding paying taxes, both among individuals and corporations. But fraud in those areas does not appear to concern those MPs' busy with proposing tougher legislation with which to target the poor.

------------------------

English version: Patricia Brett

(Editing by Graham Tearse)