On Thursday May 3rd, President Emmanuel Macron touched down in New Caledonia for a three-day visit to this French overseas territory in the Pacific Ocean. The visit is seen an an important one for the future of New Caledonia and its Kanak people, coming six months before the referendum on full independence taking place on November 4th.

But the visit also coincides with important and unhappy anniversaries of the region's recent past. On May 5th it will be exactly 30 years since the deaths of two gendarmes and 19 Kanak rebels in a bloody siege on the island of Ouvéa. This followed the kidnapping of 31 gendarmes by the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS) who held them hostage in a cave, while demanding talks with the French government over independence for New Caledonia. Four gendarmes had been killed by the group when they snatched the hostages. It has been claimed that a number of the kidnappers were shot dead after they had been detained.

Then, almost exactly a year later, on May 4th, 1989, as Ouvéa prepared to lift official mourning after those tragic events, two nationalist leaders Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yeiwéné Yeiwéné were killed by a separatist who felt the two men had betrayed the cause by agreeing to a peace process with the French authorities.

Both events still cast a long shadow over today's politics in the archipelago. Anthropologist Alban Bensa, a specialist on New Caledonia and the Kanak peoples, wrote recently in L'Humanité Dimanche weekly magazine that “beyond the tragedy that could have been avoided [Ouvéa] encapsulates all the elements of the Caledonian question that arise today”. Meanwhile journalist and director Walles Kotra, director of the overseas service at public broadcaster France Télévisions, describes Ouvéa as “a wound which was so violent it has forced us to open up new avenues with the state and between ourselves. We had to rise above ourselves.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

As the November referendum approaches, a moment when the archipelago confronts its destiny, the memory of what happened on Ouvéa acts a form of political, historic and memorial matrix of New Caledonia.

The presence of the president of the French Republic on Ouvéa on May 5th, exactly thirty years after the bloody massacre in the caves, will therefore be closely scrutinised. This is not just because Emmanuel Macron will be the first president to visit the site, despite reservations expressed by Kanaks related to those who were killed in the assault in 1988. It is also because what happened, on two occasions, on this small atoll north of the main island Grande Terre, provides a structure and a backdrop both to the institutional process that is currently underway and the current political differences.

“This memory remains really sensitive and not just on the Kanak side,” says the director Mehdi Lallaoui, currently in Ouvéá to continue the documentary work he began with his film, Retour à Ouvéa.

But if the history of Ouvéa has an influence on the decisive events in New Caledonia today, it is not just because of the drama of May 5th, 1988, which occurred between the two rounds of the French presidential election involving the incumbent socialist president François Mitterrand and his conservative prime minister Jacques Chirac.

For the importance of Ouvéa in today's political climate locally is also due to what happened a year later on May 4th, 1989, during a ceremony to end the formal mourning for the 19 Kanaks who had died during the cave attack. On that day the two main leaders of the FLNKS, Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yeiwéné Yeiwéné, were gunned down by a man called Djubelly Wéa.

This former pastor and FLNKS member, a leading figure from the Gossanah tribe in New Calaedonia and sometimes considered as the mentor of the group who kidnapped the gendarmes, had opposed the peace accords and amnesty brokered by the French prime minister's office after the Ouvéa killings of 1988. Wéa was himself killed by Tjibaou's bodyguards in the ensuing shoot-out.

These murderous episodes are constantly replayed over and again despite, and perhaps also because of, the work carried out in New Caledonia to come to terms with its past. These echoes of the past carry even more weight because the memorial ceremonies on the archipelago are not formal and institutional, and instead blend the political with the informal. An example are the sketches performed again and again by pupils at the École Populaire Kanak primary school on Ouvéa, telling the tragic story of events at what was known as Gossanah Cave.

At the forefront of these past traumas is the relationship between the French state and the Kanaks. As Mehdi Lallaoui says “though being able to speak out gives a sense of structure to Kanaks, this has been confiscated, kidnapped, buried with the amnesty”. He continues: “In spite of the amnesty laws, some ask whether we can go back over what happened, in particular revisit the cold-blooded killings of the wounded and the young despite the fact they had surrendered.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Among the most vociferous voices in favour of revisiting the past is that of Darewa Dianou, whom Mediapart met at Nouméa on Grand Terre in the autumn of 2017. The vice-president of the Kanaky Truth and Justice Committee, he is the son of Alphonse Dianou, the leader of the 1988 hostage takers who died from his wounds several hours after the assault on the cave. Darewa Dianou says that “today it's the state who are giving the instructions but who do they think they are? They killed my father and then, afterwards, they come and say they're going to grant us independence? We've never expected anything from the Republic. So, Macron wants to change everything? He needs to be told that the Sixth Republic [editor's note, in other words the successor to France's current Fifth Republic] is the Kanaky Republic!”

However, even though there are defiant voices in both camps, the institutional process triggered after the bloody events of Ouvéa did manage to bring an end to a period of violence that had occurred between 1984 and 1988, marked by deaths on both sides and a creeping militarisation across the archipelago.

The Matignon-Oudinot accord of 1988 was followed by the Nouméa accord of 1998. This provided for the implementation of “negotiated decolonisation”, arranged for the transfer of political, institutional and economic powers and forged the conditions for a “common destiny” that would form the basis of Caledonan citizenship. This process has finally culminated in the holding of an independence referendum in November which will ask the following question: “Do you want New Caledonia to accede to full sovereignty and become independent?” It requires a straight yes or no answer.

However, the calming of relations between the Kanaks and the French state is not just down to the institutional process started by the socialist government of the prime minister Michel Rocard after 1988 and pursued since then. It is also the result locally of a long and constant work of recognition and forgiveness between the families of the separatists and gendarmes. One notable result of this work was the ceremony that took place on April 22nd this year, and which started the commemorations that will end on Saturday May 5th.

April 22nd marked the thirtieth anniversary of the initial attack on the gendarme post at Fayaoué on Ouvéa which led to the deaths of four gendarmes and the kidnapping of many more, who were then taken to the cave as hostages and held during the siege.

The ceremony took place in front of a remembrance stone dedicated to Edmond Dujardin, Daniel Leroy, Georges Moulié and Jean Zawadzki, the four gendarmes killed, as well as Régis Pedrazza and Jean-Yves Veron, two soldiers from the 11th Parachute Regiment who died during the later assault to free the hostages. Side by side in front of the memorial were Jean-Marie Dassule, a former gendarme and president of the April 22nd Committee which was set up to keep alive the memory of the military personnel who fell that day in 1988, Macky Wéa, a representative of the Gossanah tribe and Djubelly Wéa's brother, and Alexandre Wallepe, who was part of the separatist Kanak group which carried out the attack on the gendarme post.

Each official speaker on that day was anxious to talk about the blood spilled by all of those involved, the gendarmes, soldiers and separatists. “Every death must be included,” declared Jean-Marie Dassule. “Even if I represent the gendarmes' families, there are also the families of the 19 [separatists], the mothers...a mother's suffering is the same whether she's on the gendarme or the island side.”

Dasulle then highlighted a sentiment that is widely shared across the archipelago. “These are events from which no one emerged the winner. But they triggered a process which said 'never again!' and which has guided Caledonia for thirty years.”

Sitting at the heart of a constitutional, institutional and political process that is unprecedented in the history of France and its former colonies, and of ceremonies that are part of Kanak traditions, the bloody events of Ouvéa in 1988 have thus started to move towards some kind of resolution. Even if the fear that weapons might yet still have a say if the November referendum says 'no' to independence has not quite gone away.

'The more the generations pass, the more the emotional burden becomes impossible to escape'

But Ouvéa is also the name, place and symbol of another set of memories, made up of the pain that has existed inside the Kanak and separatist world since the assassination of Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yeiwéné Yeiwéné by Djubelly Wéa.

This story has divided the Kanak people according to their clans, generation and political affiliations, but also according to the image they have of their land, their history and the nature of the sovereignty that they want it to have.

Darewa Dianou, for example, still criticises the Matignon-Oudinot accord; the support given to this agreement by Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yeiwéné Yeiwéné unnerved part of the separatist side. The young man, whose father died in 1988, considers the accords to be “a betrayal”. He says: “If it starts with a betrayal, all the rest is simply a betrayal.” His preferred model is still Vanuatu, a Pacific archipelago to the north east which became independent in 1980 despite the country's poor socio-economic situation. “There they don't have to stage a march to demand a road!” he says. “They try to accentuate their traditions as much as possible. It's the happiest country in the world!”

Dianou's stance remains a minority one, however, especially since the forgiveness and reconciliation process that has been implemented. It has been led by the widows of Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Djubelly Wéa and the pastor Tom Tchako and has sought to reconcile clans on Ouvéa, from Hienghène, where Tjibaou was born, and from Maré where Yeiwéné Yeiwéné came from.

This process, portrayed in Tjibaou, le pardon ('Tjibaou, the pardon') the documentary made by Walles Kotra and Gilles Dagneau, has been an infinitely complex, slow and painful mechanism but one which, in the end, has enabled the inhabitants of Ouvéa to emerge from the isolation into which they had plunged after Djubelly Wéa's killings. Wéa's murder of the two men was made even more incomprehensible and sacrilegious, says Mehdi Lallaoui, because it took place “during a traditional ending of mourning, one of the most sacred ceremonies there is”.

The reconciliation process has also been made both more necessary and harder by the fact that Ouvéa is a confined area where everyone knows each other; Jean-Marie Tjibaou's adopted daughter herself came from the same Gossanah clan as his killer, Djubelly Wéa. A reconciliation process is also not an inherent part of Kanak culture.

Indeed, Walles Kotra points out that at the start the impetus for the reconciliation process came not from “our institutions or our traditions but from the desire of two women. Marie-Claude Tjibaou's argument was that we couldn't live such a legacy to the children. The more the generations pass, the more the emotional burden becomes impossible to escape”. Recalling the archipelago's history, Kotra continues: “In 1878 the great chief Ataï was captured by French soldiers following betrayals, and this story still weighs upon us, because it wasn't able to be sorted out at the time, so resentment set in and it's difficult to find reconciliation 60 or 70 years after.”

But striking as it is, the reconciliation process is not enough to encompass all the different political, cultural and personal divides that still run through the Kanak world ahead of the November referendum, whether these differences are strategic or structural, whether they are more about symbolic issues or about how economic power will be carved up. “Differences in analysis and stance remain inside the independence world,” acknowledges Mehdi Lallaoui.

But the director says these differences need to be kept in perspective. “The Ouvéa commemorations will coincide with a great FLNKS convention which will start the campaign for a yes vote in the referendum,” Lallaoui says. “Despite their differences the Kanaks have managed to draw up plans for a society which outline a multicultural nation and a shared society.”.

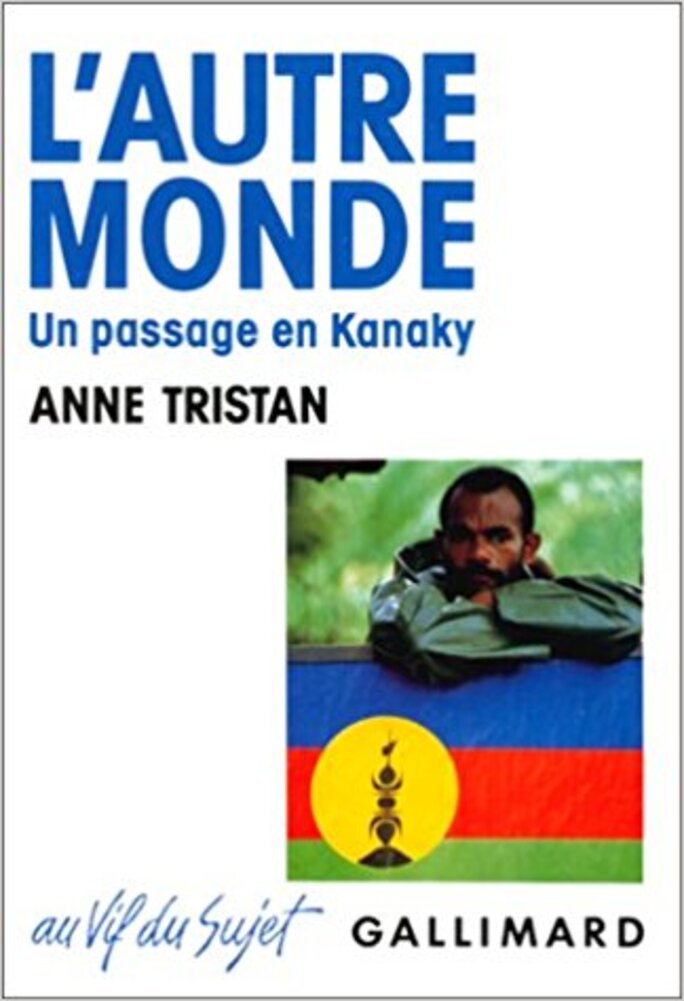

The journalist Anne Tristan, who went to live on Ouvéa for several months after the 1988 tragedy, then wrote a book called L'Autre Monde. Un passage en Kanaky ('The Other World. A Visit To Kanaky'), published in 1990 (see left). In her conclusion she wrote: “By dying at the same time, Jean-Marie, Yeiwéné and Djubelly, these three figures who so strongly incarnate the cruel contradiction of their struggle, left the issue hanging. Their death didn't resolve it, it tragically revealed its scale. The living remain with the same dilemmas in front of them. Should the break with France be violent or not? And is the break with the white world, its way of life, its towns which kill the identity of people attached to their land, desirable, possible – and if so, how? The answers, as the established expression goes in Kanaky, will emerge over time.”

Since then time has, at least partly, done its job. Not only has it led to some solutions being put forward, it has also led to some questions being changed. These are now posed less in terms of a clean break than with the idea of sharing, with all the different meanings that this last word entails. It is as if Ouvéa's bloody frenzies of May 5th, 1988 and May 4th, 1989, represent such a trauma that the majority of the inhabitants on New Caledonia want to avoid any return to them.

Nonetheless, the anthropologist Alban Bensa is aware of the possible replaying of New Caledonian history, noting that the events of 1988 were neither the start of the violence nor its definitive end. He warns: “The situation is a lot less calm than is said.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter