On May 27th 2019 two women and 16 men from Sri Lanka arrived to claim asylum in one of France’s furthest-flung territories: the Indian Ocean département or county of Mayotte. Barely a fortnight later, 12 of the 18 had been deported and flown to Colombo on an expensively-chartered plane in a move designed to discourage other Sri Lankans from following in their footsteps.

No sooner had the Sri Lankans – the first ever to reach Mayotte – set foot on dry land that day in May than gendarmes picked them up. To ensure they did not enter French territory, they were immediately placed in a holding facility as officials assessed their status.

All claimed asylum. Only six were given leave to pursue formalities that could lead to their receiving residence permits. The others saw their claims swiftly rejected first by the Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), the government agency that deals with refugees and stateless persons, then by Mayotte’s administrative court. On the instruction of a judge, they were then taken back to the holding facility pending their deportation.

In early June, Mayotte’s prefecture contacted Avico, an aviation firm, to charter an aircraft to take the 12 back to where their journey had begun. Email exchanges seen by the investigative website Le Poulpe show that the Mayotte prefect’s chief of staff and the French interior ministry unit dealing with irregular immigration took a keen interest in the case.

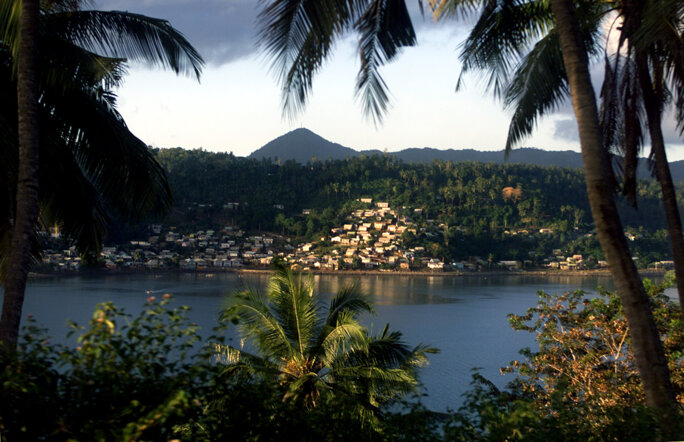

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Le Poulpe has seen three quotes sent to the prefecture, with various departure dates and flight routes, with and without a stopover in the Seychelles. Prices ranged from 159,275 euros to 265, 200 euros for a 134-seat Airbus A320 or an A318.

In their quest for the swiftest travel arrangements the authorities had to put up with some hiccups: according to one of Avico’s emails, an initial flight scheduled for June 5th was cancelled for lack of authorisation from Sri Lanka, despite the intervention of France’s foreign ministry at the behest of the interior ministry.

That same day, the prefecture’s director of immigration emailed Avico to ask if it could “check again whether a company, including one that operates in our area, even if its fees are high, has any availability before noon on Saturday.”

The prefecture seriously considered chartering an even more expensive flight, for over 250,000 euros. “The state takes its responsibilities seriously, even if it costs a bit of money,” said Julien Kerdoncuf, the deputy prefect in charge of irregular migration.

Plan B also had to be abandoned within hours because its operator, Titan Airways, could not put a crew together in time. A private plane finally took off on June 12th according to local press reports. The Mayotte prefecture said it was unable to say how much it cost. “Paris paid, I don’t know the exact amount. What I can tell you is that it was at the lower end of the various quotes,” said Kerdoncuf.

However, the lawyer representing the 12 Sri Lankans, Marjane Ghaem, said “an astronomical amount” must have been spent to send her clients home.

“At the hearing for the second extension of the placement in the holding facility, the prefecture’s chief of staff said the state would do all it could to deport them, even if it meant spending a lot of money,” she added.

For several years, irregular migration has been a hot issue in Mayotte, which became a fully integral part of Metropolitan France in 2011, in the wake of a 2009 referendum that saw its status change from that of an “overseas community” to the country’s 101st département or county.

Every day people in search of a better standard of living arrive by boat from other islands in the Comoros chain, which, unlike Mayotte, declared independence from France in 1975. Only 45 percent of Mayotte’s inhabitants were born there. Other migrants travel from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi and Rwanda.

“Xenophobic groups exert considerable political pressure to send [irregular migrants] back to their country,” explained Ghaem.

When the Sri Lankans arrived on Boueni beach, local residents protested vociferously.

“Even if the cost was not negligible, a message had to be sent to potential immigrants so that they understood they would be deported immediately. We also wanted to show the people of Mayotte that the state is doing something,” said Kerdoncuf.

“By allowing these people onto [French] territory, the social, political and public order costs, even if hard to quantify, would have been even higher than that of chartering a plane,” he added, referring to “the tense climate around immigration” on Mayotte.

In the recent elections for the European Parliament, Marine Le Pen's far-right Rassemblement National – formerly the Front National - won more than 45 percent of the vote there.

“The French state has forgotten Mayotte. There are so many areas needing investment and all of a sudden money is found for this. I am very surprised,” said Ghaem. Some 84 percent of Mayotte’s population live below France’s poverty line, according to a 2017 report by the national human rights commission.

The lawyer is planning to appeal the second ruling that kept her clients in the holding facility. “There were irregularities. The courts played politics, not justice.”

The stance taken against irregular migrants appears to be much tougher in Mayotte than the rest of France. Some 36 percent of all migrants detained across the country are held in Mayotte, according to a recent report by a group of non-governmental organisations. Last year, 1,221 of the 18,697 people who passed through administrative detention centres were minors.

In many cases, the report said, deportations occurred without their legality being verified by a judge.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

--------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Anthony Morland

Editing by Michael Streeter