First the good news for the French government; its key vote in the National Assembly on Tuesday on the so-called Fiscal Pact will be won. The bad news for the socialist administration is that victory may only be guaranteed by the fact that MPs of the Right will vote overwhelmingly for ratification of the European Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG), to give the treaty its official name.

For many MPs on the Left of the political divide, including some from the majority Socialist Party, are determined to vote against what they see as an “austerity pact” despite desperate attempts by prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault and his ministers to galvanise support for the controversial adoption of the European treaty into French law. They consider that the pact, which obliges national parliaments including France's to pass legislation enshrining the so-called 'golden rule' that nations should have a structural deficit of only 0.5% of GDP or less, favours EU-imposed austerity over economic growth.

One political difficulty for President François Hollande is that during his election campaign he opposed the pact which was signed by his predecessor President Nicolas Sarkozy, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other EU leaders on March 2nd 2012. Hollande said he would not endorse the agreement unless it contained measures to promote growth. Once in power Hollande obtained support for a 120 billion euro Compact for Growth and Jobs which he said allowed him to back the Fiscal Pact. However the pact itself remains essentially the same as the one negotiated between Sarkozy and Merkel.

Here Lénaïg Bredoux and Mathieu Magnaudeix sum up the mood in the National Assembly ahead of the key vote on Tuesday 9th October, while below Mathieu Magnaudeix and Liza Fabbian look at the mood on the streets from protesters who turned out in number last week to voice their disapproval of the 'austerity pact'.

-----------------------------------------

In the Assembly

In the end, Jean-Marc Ayrault changed little or nothing. Despite the prime minister's efforts to get a unanimous vote from Socialist Party MPs for the controversial Fiscal Pact, it is thought that up to 20 MPs from the majority party may vote against the measure of abstain on Tuesday. They will be joined in this by virtually all MPs from the Greens (Europe Écologie – Les Verts), who have two ministers in the government, and those from the hard-left Front du gauche.

Indeed, when the premier began to speak at 4.30pm on this crucial topic the Socialist benches in the National Assembly chamber were not full, with about 65 socialist MPs absent. “I’m attending a committee,” said one MP explaining his absence. Another claimed, perhaps less plausibly, that he “had a dentist's appointment”. All this despite the fact that Matignon – the prime minister's official residence – had sold his speech as a “keynote address” and a “political test” for the government.

For half an hour Ayrault sought to persuade those who had “doubts, in some cases deep doubts”, and he spoke to those on the Left about a “social Europe” and about the transition to new, renewable energies in the future. But of the fiscal pact itself he spoke as little as possible. The prime minister glossed over the fact that during his election campaign François Hollande had described the text signed by his predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy as catastrophic for economic growth, and that the treaty now had to be signed because the new president had failed to get it renegotiated. Instead Ayrault insisted that the 120 billion euro growth pact plus an agreement to tax financial transactions and initial steps towards a European banking union were enough to signal a “reshaping of Europe”.

The prime minister told the National Assembly: “It is this decisive change of direction for the future of the European project that I have come here today to ask you to support. Formally, you will be asked to vote for the ratification of the treaty [TSCG]. But through your vote it's the reshaping of Europe that you will be proclaiming.” Meanwhile, behind the scenes, advisers at Matignon spelled it out even more starkly: “What we're saying to members of parliament is that you're not voting for or against the treaty but for or against reshaping Europe. It's a real strategic choice.”

A sign of the government’s nervousness over the vote has indeed been its attempts to raise the political temperature in recent days. The prime minister told MPs that the future of the euro itself was at stake and said that the “consequence of a negative vote in our country would be, as you well know, a political crisis and the collapse of monetary union”.

The prime minister’s office has also stressed that a no vote would send out negative signals not just to the markets but also to other EU members. “We are in a shop window at the moment and our partners are watching carefully what happens in France because they have suspicions as to the real capacity of the government to respect its European commitments,” said a source. Matignon believes that only a resounding ratification of the pact – which was sought after and inspired by Germany – can give President Hollande the room for manoeuvre he needs in the future to negotiate with German Chancellor Angela Merkel on other issues.

This is why Ayrault is so keen to reduce to a minimum any dissenting votes from the government’s own benches. “We want to get the text adopted without needing the votes of the Right, that's the aim and it is achievable,” says a source at Matignon.

It seems that Ayrault speech may have limited the damage, but done little else. Though his comments were acclaimed by his own MPs, there was little real enthusiasm. After the speech relatively few Socialist Party MPs came out publicly to defend the government's line on camera. Those that did trotted out familiar phrases such as “re-shaping Europe”, “growth” and “François Hollande’s commitments”. Some observers felt their hearts were not really in it. “It's not easy for them,” said one veteran commentator. “They certainly don't want to make a fuss about it.”

Critics of the measure were more visible. Jérôme Guedj, Socialist MP in the Essone département (county) south of Paris, said he would still vote against the treaty, in a gesture that he and other Socialist MPs have described as a “'no' of support” for President Hollande. “It's a measly treaty. It's not up to the job of dealing with what's at stake and doesn't allow for the creation of a new balance of power towards a federal, social Europe and for the modification of the statutes of the European Central Bank,” he said. Another Socialist MP Mathieu Hanotin from the Seine-Saint-Denis département in the Paris region said that the fiscal pact would make it harder to get out of the crisis, especially for countries in southern Europe. “I'm not interested in the least-bad solution, the lesser of two evils or small steps,” he said. “We don't have the time to wait, we need a real remedy. That's why I won't vote for this treaty.”

Despite the discontent from some, the government feels confident that it has at least contained the worst of the rebellion. At a show of hands during a meeting of Socialist MPs this week just 13 indicated they would vote against the measure, with two more abstaining, out of 200 present. “They are a tiny minority,” said the young Hollande supporter and MP for the Côte d'Or département in Burgundy, Laurent Grandguillaume. He claims that the anti treaty movement has already run out of steam among the Socialist majority.

However, one MP claimed that opponents had not been told in advance of the show of hands vote and that “we weren't all there”. Other MPs are still hesitating over which way to vote, having come under pressure from the government to back the official line.

Organised protest

“Wanted, to answer to democracy. Reason: wants to impose the fiscal pact despite his commitments and without consulting the people.” So read one of the banners in last Sunday's protest as demonstrators gathered on the streets of Paris to voice their opposition to the Fiscal Pact currently being debated by the country's MPs.

That banner was far from being the only unkind reference to President François Hollande, who was elected on in early May. “In the spring we elected him and in the autumn he betrayed us” read one angry placard, while another clearly voiced regret at having voted for him: “If I'd known on May 6th 2012, I wouldn't have turned up”. Yet another mocked the call by François Hollande in his campaign for the electorate to turn out and make their vote count for something. “Here's where a useful vote leads you,” it read.

The march, organised by organisations and parties on the radical-left, notably the Front de gauche - made up of the French Communist Part and the Parti de gauche - attracted up to 80,000 people, at least according to the organisers themselves. The police prefecture did not give figures as it usually does, so the actual numbers are hard to pin down, but the march certainly stretched for several kilometres through the streets of the capital.

The main purpose of the gathering was to protest against the Fiscal Pact that the government wants to ratify but which opponents claim will simply herald “permanent austerity”, though it was also the chance for the country's habitually divided far-left to march together.

A total of 60 different organisations and parties took part, including the New Anti-Capitalist Party (NPA), the global justice movement Attac, the group of economists called Économistes Atterrés or 'Appalled Economists', and trade unions and trade union-affiliated organisations.

The marchers were led by a group of feminist associations whose spokeswoman Christiane Marty, said: “The crisis is hitting the working classes and poor people hard. Among them are the young and immigrants but also women – they are the ones who are most often under-employed, stuck on low wages and hit by cuts in social services.”

Many of the slogans referred to the crisis across Europe as a whole, notably the suffering of people in Greece, Spain and Portugal, all caused by “austerity programmes”, said Pierre Khalfa of the Copernic Foundation, which fights against economic liberalism. But there was also vocal opposition to the recently-announced 2013 budget in France which according to Khalfa will “lead to drastic cuts in public spending”.

There were, however, some notable absentees from the march. MPs from the left of the Socialist Party and Green (EE-LV) MPs and senators who will vote against the Fiscal Treaty next week declined the invitation to attend. This is because their hostility to the pact is matched by their antipathy towards Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the Front de gauche's presidential candidate earlier this year and one of the main speakers at last weekend's rally.

For Mélenchon himself the march was a triumph. “This is the day that the French people start a movement against the policy of austerity,” he exclaimed. And the Parti de gauche leader singled out the prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault and his “technocratic” ministers for criticism. “Completely closed off, he's dividing the Left, he's allying himself with the Right against the rest of the Left,” he said. “They either change their position or we change our representatives,” said Mélenchion, clearly making a bid for the Parti de gauche to become the main alternative to the Socialist Party on the Left.

Meanwhile the First Secretary of the French Community Party (PCF) Pierre Laurent was more measured in his comments. “This demonstration against austerity is a step ahead of the government,” he said. “All the forces on the social, trade union and political Left are in the process of uniting to stop austerity. It's we who will give the Left courage. Let's stop mistrusting the signs coming from the people!” He concluded: “Today is a starting point, it will continue in the weeks and months to come.”

Annick Coupé, of the trade union federation Solidaires, too, warned of new protests to come. “If we had had more time, we could perhaps have mobilised as we did in 2005 against the Treaty,” she said, referring to the successful campaign by the Left then against plans for a new EU Treaty that was eventually rejected by the French people in a referendum on May 29th 2005. “But this day at least enables us to start to create a new balance of power on social issues.”

The word from the street

Liza Fabbian spoke to some of the rank and file protesters on the march to hear their fears about the impact of the Fiscal Pact.

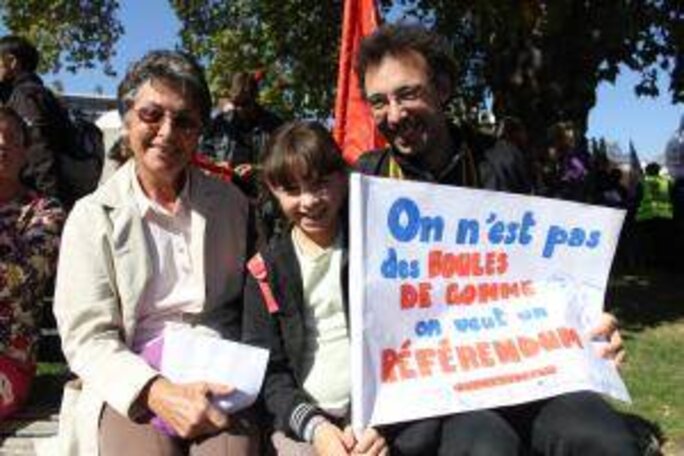

Stéphane, 43 years old (Parti de gauche): “There’s a very strong democratic hankering for a referendum [on the Fiscal Pact]. We want to see a Europe being built for the people, a Europe of brotherhood that doesn’t seek to constrain and oppress through austerity. We want to share our wealth. I can’t say I’m disappointed with François Hollande’s policies, I wasn’t expecting much of him. It’s the same austerity policy we’ve been subjected to since the mid-1980s.”

Anonymous, 22: “We have come to demonstrate against a treaty that’s going to force us to pay more and more for a bottomless debt. It’d be better to lock up the crooked bankers and the speculators! If the worst comes to the worst, we could follow Ireland’s example and give the people a say in government againwith a referendum on this treaty. François Hollande is in the same tradition as Sarkozy: there’s nothing social about his policy.”

Odile (anarchist): “I’ve voted only once in my life, in 1981. As a matter of fact, I think it was from then that my position changed, I lost my illusions. I’m more and more worried about my children’s future.”

Arnaud, 32 (French Communist Party): “The golden rule is going to prevent the development of public services. With the signing of the treaty, the handful of reforms that were promised will not take place. I knew when I went to vote for him that François Hollande wouldn’t honour his commitments. But what he’s doing now is anti-democratic, the French didn’t vote for free-market policies. He should have tried to renegotiate as he’d promised. By avoiding debate, he’s evading popular pressure.”

Émilie, 31: “Signing the treaty is liable to give the government an additional argument not to honour its commitments and to go back on its promises with the argument of fiscal discipline imposed by the European Commission, which is not a democratic body.”

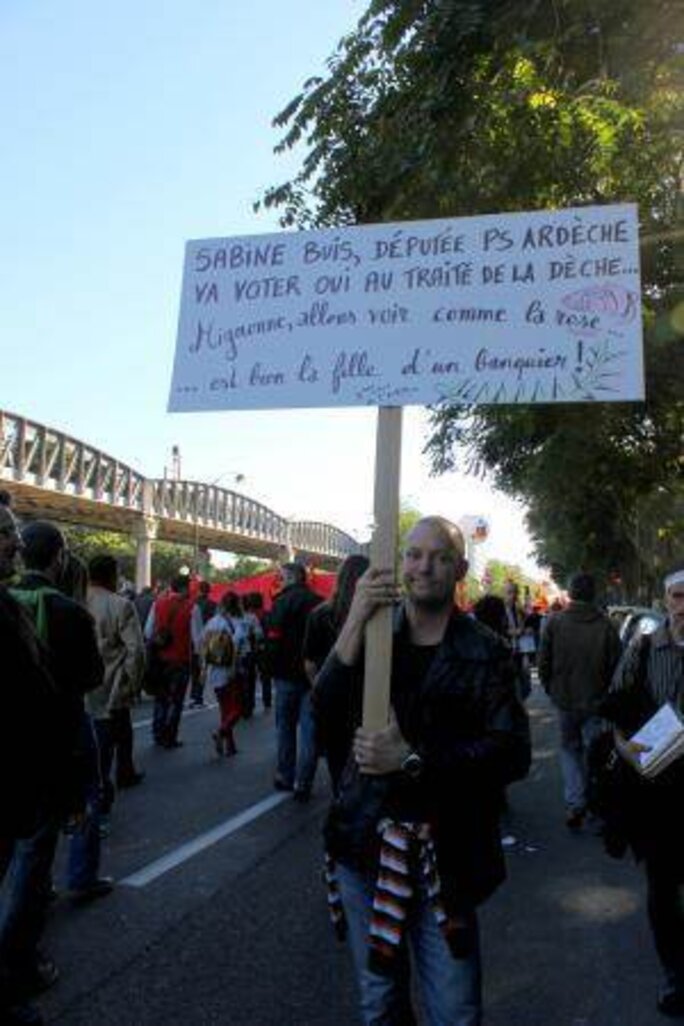

Cyril, 38 (Parti de gauche): “In 2005, our MP Sabine Buis [representing the Ardèche département in southern-central France] voted against the European Constitution to go against Sarkozy. But this time she’s going to vote for the treaty because she’s got to hold on to her seat. Now they have to follow one man. Solidarity with the government takes precedence, along with political manoeuvring. Prohibiting debate, now that’s the Socialist Party in all their glory.”

Anita: “For a very long time I’d been expecting this popular reaction against the policy the government are inflicting on us. Once again they’re putting economic problems before social problems. If we voted Left, it was so there’d be a change, not a continuation of austerity. We must also speak out in solidarity with the other European nations who are hurting.”

Laurence: “We’re afraid that this policy serves the far right. I didn’t think the PS [Socialist Party] would revolutionise France, but we really are faced with a promise not kept. What’s more, I’m sorry there aren’t more activists here from Europe Ecology–The Greens. They should speak out if they disagree.”

Claude, 65 (FASE – Federation for a Social and Ecological Alternative): “Leading people to believe that the government is pursuing left-wing policies, now that’s bad. That’s going to discourage all those who thought they were voting for change. We’re sick and tired of being had, as we already got had with the Treaty of Lisbon.”

Vincent, 20 (Parti de gauche – Party of the Left): “We’d rather vote than be subjected to permanent austerity. That François Hollande should refuse the referendum is a disappointment we’d been expecting. Other things are harder to accept, like when Arnaud Montebourg [Minister of Productive Recovery], who is supposed to stand for industrial recovery, asks the unions to show some economic responsibility, while the redundancy plans are spreading.”

Yann, 41 (FASE – Federation for a Social and Ecological Alternative): “A different Europe is possible, a Europe of love and solidarity, which has nothing to do with the one they want to get us to accept, without people’s governance, and which is bringing countries to their knees for the benefit of bankers and stockholders. People are already disappointed, and I’m not even talking about the redundancy plans or the expulsions. It’s sickening. Even on the 75% [tax on incomes of over one million euros a year a controversial campaign pledge], Hollande has backtracked, saying it’ll be a temporary measure. But tax hikes, that’s not temporary!”

----------------------------------

English version by Eric Rosencrantz and Michael Streeter