President François Hollande wants France to take the lead in the transition to green energy. He told an environmental conference in Paris at the end of November that the country should now champion “environmental rights” in the same way it has been a beacon for human rights. The meeting, called to set a French road map for this transition to clean energy, was a prelude to the major United Nations Climate Change Conference to be held in Paris in a year's time. “We cannot be convincing if we have not ourselves committed to strong action,” Hollande pointed out in his opening speech.

Yet when it comes to renewable energy, France still has a long way to go to be convincing. Since Hollande was elected in May 2012, hardly anything has been done to boost renewables. A handful of small, scattered and unpublicised projects have been given the go-ahead, and these are rarely trumpeted and have received little political backing.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

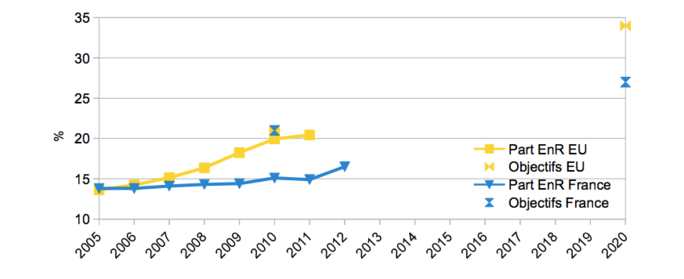

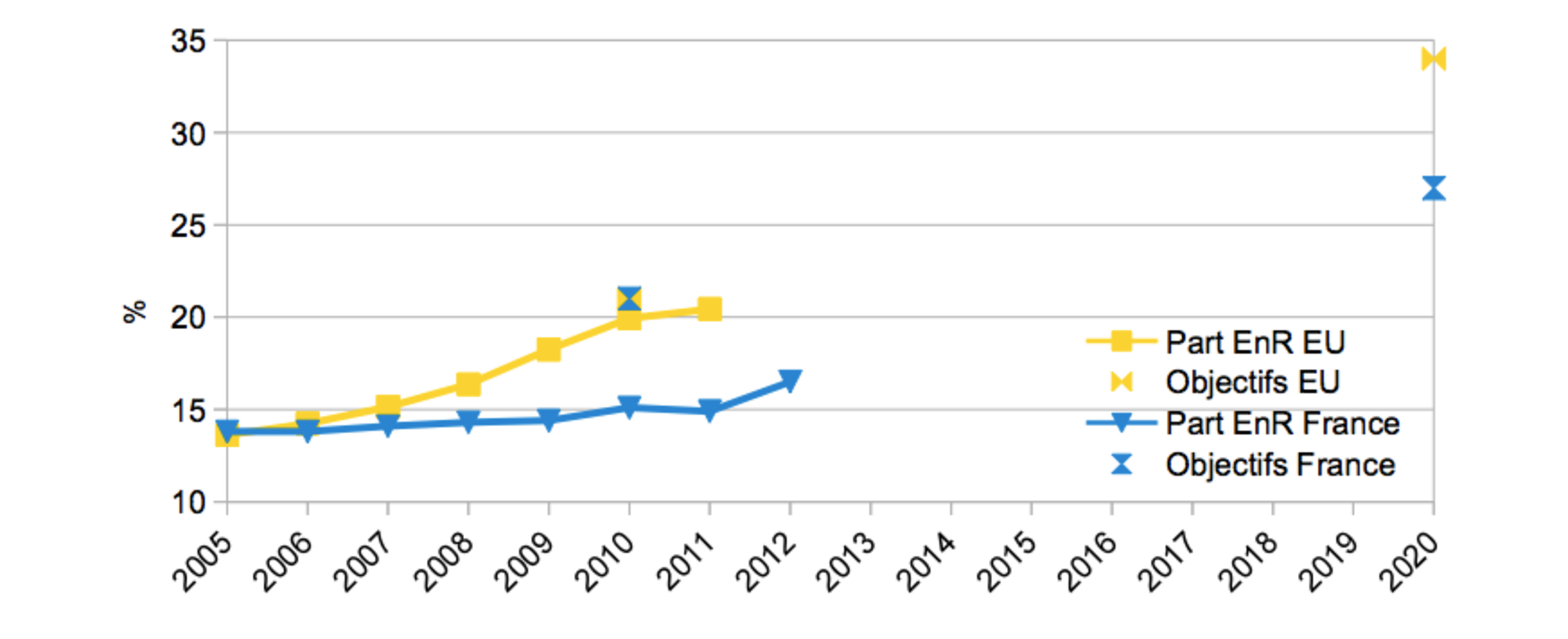

Renewable sources account for 13.4% of energy generation capacity in France and supply 16.6% of its electricity, according to Eurostat, the European Union's statistics institute. But this comes almost entirely from its hydroelectric dams which were built decades ago. Take them out of the equation and the picture is pathetic: wind farms provide 3% of France's electricity, and solar and biomass each account for 1%. In urban areas, just 0.8% of electricity comes from solar.

Even if hydroelectric dams are included, France is still far from achieving legally-binding targets for renewable energy of 23% by 2020 and 27% by 2030. Already it seems certain the first target will not be met on time. For wind power, with a national target of reaching 19 gigawatts (GW) of installed capacity in 2020, only 8.5GW was up and running by June 2014. “We would need 1.7GW more by the end of the year, but we will probably be at around 900 megawatts (MW),” says Sonia Lioret, managing director of France Énergie Éolienne (FEE), a wind power trade association.

Solar is also behind schedule. At the end of June this year total capacity connected to the network broke above the 5GW mark, but the cumulative goal under all the regional climate plans (1) is more than 15.5GW for 2020. To meet that would involve tripling installed capacity in the next five years, but the annual rate of development has been far below that in 2014.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The commission that regulates gas and electricity markets, the Commission de Régulation de l'Énergie (CRE), forecasts that by 2020 solar will provide just 8GW and land-based wind power will have reached 15GW, still lower than the 19GW target. It expects only 2GW of offshore wind power by then, compared with the target of 6GW, and 500MW of biogas instead of the targeted 625MW. The ministry for ecology, sustainable development and energy has just put the construction of 1GW of extra offshore wind capacity out to tender.

When it comes to renewables France punches well below its economic weight, according to Yves Marignac, who heads the Paris office of the anti-nuclear energy consultancy WISE (World Information Service on Energy). The country accounts for 15.7% of Europe's gross domestic product (GDP), but according to his estimates, only 5.6% of the continent's wind power and 7.9% of its solar power by value. Not a single French company figures among the top ten global manufacturers of wind turbines or in the top 15 manufacturers of photovoltaic equipment.

Yet elsewhere, renewable energy is developing at break-neck speed. For the first time ever, in 2013 new installed capacity in renewables was far ahead of all the other energy sources – nuclear power, coal, gas and oil – accounting for 58% against 42%. And in 2012, Japan, China and Germany produced more electricity from 'new renewables', excluding major dams, than from nuclear energy, another first. In Spain, which gets some 20% of its electricity from nuclear power, wind power has become the biggest single source of energy (2).

---------------------------------------------------------------

1. In 2007 the then-president Nicolas Sarkozy initiated the Grenelle de l’Environnement, a series of round-table discussions to define public policy on environmental issues. The Schéma Régional Climat Air Energie (SRCAE) were born of this process to define and monitor aims and objectives on climate change, air quality and energy generation at regional level.

2. For details see The World Nuclear Industry Status report 2014 chapter on Nuclear Power versus Renewable Energy.

Military opposition

Enlargement : Illustration 3

France's failure in renewables is most obvious in solar power. Readers of Jeremy Rifkin's latest book, 'The Zero Marginal Cost Society', will have discovered an America with roofs and parking lots covered in solar panels. In France, you still only see tiles and slate. Under our current system there is no real incentive to move in this direction.

France has instead copied Germany in setting tariffs for utilities to buy solar power – Electricité de France (EDF) is obliged to buy electricity produced by solar installations at prices fixed over 20 years. This feed-in tariff varies in relation to the size of the installation but is above the price for nuclear-generated electricity.

The feed-in tariff is in fact a form of aid that is ultimately paid for by consumers, as it is funded by the Contribution au service public de l'électricité (CPSE), a contribution added to electricity bills, which was brought in to compensate electricity utilities for shouldering this obligation. But, because it was based on excessively high, inflation-linked feed-in tariffs, the system engendered a speculative bubble, helped by tax credits brought in under the Grenelle de l’Environnement at the start of Nicolas Sarkozy's presidency.

“In 2006 tariffs for the purchase of photovoltaic [power] were set at too high a level, well above what was necessary to ensure the desired development,” says the Réseau pour la transition énergétique (CLER) a trade association for the renewable energy sector. “In just a few years, the industry has made extraordinary progress which has sharply reduced the price of equipment, bringing about a total dislocation between the increasingly low cost of installations and the level of the purchase price, which goes on rising.”

That means higher costs for the nation. CLER calculates that since the contribution to electricity bills was brought in, contracts to buy photovoltaic electricity represent a cumulative total of 5 billion euros, essentially for deals signed between 2008 and 2011. Between 2014 and 2025 the total cost of contracts signed before 2013 will amount to some 24 billion euros.

A moratorium was introduced in 2010, and then feed-in tariffs were drastically reduced. This brought everything to a halt and put a stop to the sector's development, a blow from which it is still finding it hard to recover. All France's solar photovoltaic module makers went out of business. Photowatt, which was bankrupt, became an EDF brand, and has an uncertain future.

Those left in the solar industry had to turn elsewhere. Exosun, a French firm that is one of the world leaders in solar trackers, which orient panels towards the sun, is now focusing on international business. “There is no sector any more. There is a slow and inexorable erosion. There is no more business in photovoltaic,” says Marc Jedliczka from HESPUL, an association involved in solar development. The sector has lost nearly 15,000 jobs in three years, equivalent to shutting five factories the size of Peugeot's closed Aulnay car plant, notes Raphaël Claustre, an official at CLER.

After two years of free fall, the number of new connections of photovoltaic installations did see a recovery in the first half of 2014. Ségolène Royal, the environment minister, has also just announced the award of 217 projects via tenders outside the feed-in tariff system. But they represent only 41 MW, not enough to resuscitate the sector.

But this appalling complexity, with five different feed-in tariffs as well as the tender system, is not the only obstacle that solar projects face in France. There are also regulatory traps that undermine the sector. For example, individuals must mount photovoltaic modules on their roofs - rather than standing on other parts of their property - to benefit from the special tariffs for purchasing their electricity. But this involves technical problems and higher costs, 30% higher according to CLER's Claustre. As a result, installing photovoltaic modules is more expensive in France than in Germany and creates technical vulnerabilities.

Another handicap is the cost of connecting to the electricity grid, which is the monopoly of ERDF, EDF's distribution subsidiary. “ERDF sets the costs and applies them. You can't negotiate,” says Jedliczka at HESPUL. Until 2010 electricity producers were entitled to a 40% discount, but this was abolished during that year's moratorium, increasing costs and creating discrimination between producers and consumers, something that is supposedly forbidden under European rules.

There is another problem too; EDF's transmission subsidiary, RTE, provides a further drain on producers. Its charges depend on producers' installed capacity on the high tension grid, but they are far from transparent, varying region by region from zero to 40,000 euros per installed MW, according to HESPUL. For wind power, getting connected to the grid can take a few years, depending on the region. FEE, the wind power trade group, found one extreme case where connection took five years. And there are no industry watchdogs one can turn to in order to take on RTE or ERDF.

The position of wind power has improved over the past two years, according to Sonia Lioret, the managing director of wind power trade association FEE. But before that, it was “catastrophic”, she says. A group representing opponents to wind power, Vent de colère ('Angry Wind'), took legal action contesting the feed-in tariff for wind-generated electricity, and as a result not a single bank wanted to finance projects. The case is still before the European Court of Justice, but the government has guaranteed the tariff to lift financial uncertainty.

That is now working, but only for a while. Paradoxically, the new law on energy transition has reintroduced uncertainty over feed-in tariffs by making it possible to create a market system coupled with the granting of premiums for new installations – something specified in a European guideline that France seems to want to apply to the letter. Last year, a new law (the 'loi Brottes') on energy eased the situation, getting rid of a system that limited the zones where wind power could be developed and the requirement to have at least five turbines per farm. These were real advances that met some of the sector's demands. But wind farms still take six to eight years to develop. They often run into opposition from the French military, who have reserved significant chunks of territory for their radars, as the country's meteorological office Méteo France has also done.

The renewables subsidy that benefits ... fossil fuels

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The main problem is a systemic one – the absence of a real market for players in the renewables industry, says FEE's Lioret. “Everything is done by contract, by direct deals. Today 80% of the volume of electricity consumed in France is not sold on the wholesale market. Small players have no margin for manoeuvre,” she says.

The French system remains one conceived by and for nuclear power, which still provides three-quarters of the country's electricity. It is centralised and rigid, with a fossilised distribution and transmission monopoly, and places EDF in an omnipotent position. The overwhelming majority of local authorities, which own their energy distribution grids, prefer to outsource the management of these to EDF, so it continues to control every stage of electricity generation.

This situation, it so happens, is highly favourable to fossil fuels. Energy regulator CRE's latest report highlights a paradox: the main tool supposed to finance renewables, the CSPE (a contribution paid via electricity bills to compensate utilities for their purchasing obligations), has in fact largely benefited fossil fuels. Of the 30 billion euros paid out under its auspices since it was created, two-thirds actually funded coal, fuel oil and gas. Wind power has only benefited from 10% of the CPSE every year, which is equivalent to 4 euros per household per year, Lioret says.

In France's overseas départements and territories, the CPSE massively finances fossil fuels. There, its cumulative cost over the past 12 years comes to 10.8 billion euros, and only 7% of this went into renewables, according to CLER. By 2025 the CPSE will have brought in 26 billion euros in these overseas territories of which a mere 19% will have been used to fund renewables. The main beneficiary of this cash windfall is EDF SEI, EDF’s subsidiary in Corsica and overseas French dependencies.

As a result there has been an explosion in fossil fuel production and revenues, notes CLER. The Ile de Sein, off the west coast of Brittany, gets all its electricity from fuel oil, a heavy contributor to greenhouse gases, while a cooperative wind project there is battling against EDF's monopoly. Tax concessions in France for fossil fuels are worth over 33 billion euros, according to calculations by Guillaume Sainteny, a specialist in ecological fiscal policy.

The issue of the CPSE contribution is thus central to understanding how the development of renewable energy has been systematically blocked. It is not suffering as a result of lack of cash; tens of billions of euros will be made available between now and 2030. But this money is badly used, partly absorbed in maintaining the energy status quo whereas it should be used to kickstart the transition towards a model based on reducing demand and cutting greenhouse gases.

Carbon dioxide emissions benefit from a hidden subsidy: the absence of green taxation. This has allowed industry - and polluting behaviour generally - to benefit from the zero cost to them of producing CO2, despite the almost irreversible damage that this causes to the atmosphere. Under these circumstances fossil fuels represent unfair competition to renewables, which need the cost of a tonne of CO2 to be high to make them profitable. For them to prosper, green energies need the principle of 'the polluter pays' to be respected. The contribution climat énergie – a levy on fossil fuels such as gas – introduced in the 2013 budget is far too small to have even the slightest effect. It has in fact become virtually invisible thanks to the sharp fall in oil prices. This has proved the greatest failing of the current government so far faced with the crucial issue of installing renewable energy capacity.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter