The campaign for France's next round of local elections on March 22nd and 29th has barely begun and already the prospects look fairly bleak for the mainstream political parties and especially the ruling Socialist Party. Abstention is forecast to reach new peaks. And this year for the first time all councillors in the nation's départements or counties are up for election at the same time, giving these polls a national slant against a backdrop of mistrust and dissatisfaction with the major parties. The Left, which currently runs 60 out of the 100 or so départements, is expected to take a beating, with the ruling Socialist Party likely to be singled out for particular punishment by the electorate.

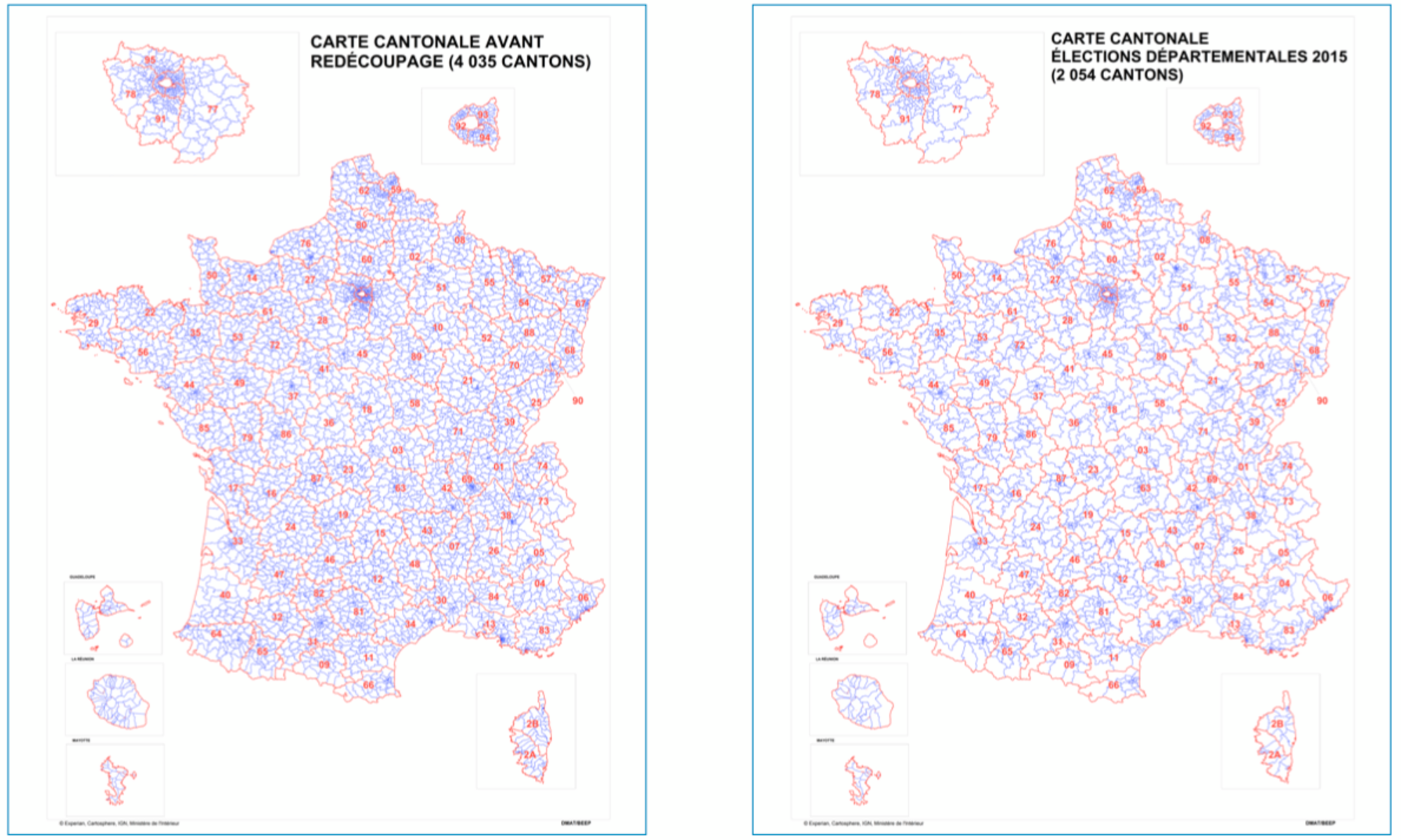

But a glance at the list of candidates compiled by the interior ministry, which can be seen here in Excel format, shows the elections will bring a significant number of fresh faces to local politics. And for the first time they will return exactly the same number of men and women to local authority seats – 2,050 of each. The number of cantons that make up each département has been halved so that each canton is larger with redefined boundaries, and in each, electors will vote for a candidate list made up of a male-female pairing.

Until now this tier of local authorities, previously called general councils – conseils généraux in French - and now to become departmental councils ('conseils départementaux'), was almost exclusively male. Women currently comprise 13% of general councillors, and in 12 départements out of 101 the figure is under 10%. Only five general councils are presided over by women. After these elections, the departmental councils will be the only representative bodies in France to have equal numbers of men and women, far ahead of the National Assembly – the lower house of the French Parliament, the Senate, the upper house, or regional councils. This equality comes fully 15 years after the first law on male-female parity was passed, and has had to be imposed on the system, as financial penalties against the political parties had failed to achieve the desired result.

Click on the map to see the current general councils' political hue:

French overseas départements Guadeloupe (PS), Martinique (Left), Guyane (independents), Réunion (centrist UDI) and Mayotte (Left) are not included on the map.

Apart from parity, there will also be a tangible rejuvenation of these councils. This is not such a tall order, given that many existing councillors are senior citizens – 6 out of 10 of them are over 60. There are also more local councillors over the age of 80 – 1% – than under the age of 30 – 0.25% (just ten councillors in all).

Nevertheless, according to the interior ministry only 2,200 of the 18,193 candidates in these elections are current councillors who are standing again. So even if they are all re-elected - which is highly improbable - the re-election rate of existing councillors will still not reach 50%. “Usually it is 60-70%,” says Aurélia Troupel, lecturer in political science at the University of Montpellier 1 in southern France and a researcher at CEPEL (Centre d’Études Politiques de l’Europe Latine – Centre of Latin European Political Studies).

This low rate of renewal is partly due to the fact that some councillors who stood for a short mandate in 2011, ahead of the current reforms, are throwing in the towel this time, while others were discouraged by the new rules and reforms affecting the size of the cantons, and which impose male-female parity. In fact, the parties have found it difficult to recruit candidates.

Another old habit is gradually being laid to rest: that of combining a mandate as a local councillor with a parliamentary mandate. Under a law passed by the current socialist government, which many in the centre-right UMP want to repeal, from 2017 it will no longer be possible to combine a local executive function, such as president or vice-president of a regional or general council or as a mayor, with a post as a senator or an MP. Some councillors have anticipated this change and decided not to stand again this time.

According to data from the Observatoire de la Vie Politique et Parlementaire (OPP, Observatory of Political and Parliamentary Life), published in part in Le Monde, 61 MPs are standing in these elections, compared with 101 who currently sit on general councils. There are also just 46 senators standing, compared with 94 who are currently also local councillors.

Départements now being sidelined

Out of those parliamentary representatives who are standing in the departmental elections, 33 are general council presidents who have clearly decided to stay the course. They include the ex-Socialist Jean-Noël Guérini (Bouches-du-Rhône), who was re-elected in the last Senate elections, centrists François Sauvadet (in the département of Côte-d'Or) and Maurice Leroy (Loir-et-Cher), former UMP ministers Dominique Bussereau (Charente-Maritime), Hervé Gaymard (Savoie) and Patrick Devedjian (Hauts-de-Seine), leading UMP MP Éric Ciotti (Alpes-Maritimes), and socialists Jean-Louis Destans (Eure), Philippe Martin (Gers), Henri Emmanuelli (Landes) and Thierry Carcenac (Tarn).

However, a mandate as a general councillor is less attractive for newly elected mayors in the biggest urban areas. According to OPP, of the 145 mayors of towns with over 20,000 inhabitants who were elected for the first time in 2014, only 38 are also candidates in this month's departmental elections. Two-thirds of them come from the Paris region, and almost all are from the centre-right UMP or centrist UDI. Their aim is to play a political role in the future Greater Paris Metropolitan Area, which will be brought into being officially on January 1st, 2016, and will inevitably be dominated by the Right given that the Left performed so badly in the 2014 municipal elections.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Click here to get a pdf of the maps of the new cantons from the ministry of the interior's website

So will the departmental elections really bring a breath of fresh air to French political life? Aurélia Troupel, the political scientist, is dubious, because if the renewal does materialise, it will concern a tier of government that is becoming increasingly marginal in the political system. “We should be pleased to see real parity on general councils, which were male bastions,” she says. “But at the same time, we are creating parity in the départements just as they are losing their aura.” The small number of outgoing councillors who are running again is, she says, a sign that the general council is losing its status amid the upheavals brought by current local government reforms.

Until now, general councillors have been esteemed public figures, deeply rooted in their communities, and 98% held another electoral mandate – as mayor or municipal councillor, on inter-municipal bodies or in Parliament, for instance. A mandate as general councillor used to guarantee political longevity and was a key step in any political career, often opening up the possibility of positions at national level. “Anchorage and stability were a real feature of the general council. But the mandate is losing its attraction, its allure,” says Troupel.

The blame lies in part with the recent changes to electoral rules, which dilute ancient fiefdoms within broader cantons, and also with the reduction of central government funding, which makes exercising the post as general councillor more difficult, particularly in rural areas. But the on-going local government reform is also a factor. “The département's uncertain future does not inspire someone looking for a vocation,” Troupel says. “This tier of government has had a question mark hanging over it for years. [President] François Hollande and [prime minister] Manuel Valls even said last year that it would be abolished. It was finally granted a reprieve, but its future powers are not yet clear.”

In fact, the law that will detail the role of départements within the new territorial organisation is still being discussed in Parliament and will not be voted on before these local elections. And what Troupel calls the “hierarchy of mandates” is being shaken up as France's regions, metropolitan areas and inter-communal bodies increase their power at the expense of towns and départements. “Numerous representatives are bypassing these departmental [elections] and are preferring to concentrate on the regional [elections] in December 2015,” she says.

To gauge the true depth of renewal in these departmental elections, it will be telling to look at the pedigrees of the 2015 vintage. There is no guarantee that politicians will stop trying to combine more than one electoral mandates, as having more than one local post at a time is not being outlawed, nor is there any limit on how many times someone can be re-elected.

The number of women elected as president or vice-president of a department will also be revealing. Will men continue to monopolise the majority of these roles despite the parity imposed on the membership of the new departmental councils? Will women remain restricted to certain roles, such as social and cultural concerns? Finally, it will be important to measure whether these elections allow representatives from different backgrounds to emerge – such as more people from the lower classes, more private-sector employees, and more councillors from immigrant backgrounds.

France's political class is “too narrow because of the accumulation of [electoral] mandates,” sociologist and political scientist Dominique Schnapper said in a recent address to the National Assembly working group on the future of institutions. “When many categories – descendants of immigrants, young people, women – feel excluded from representation, it results in a dysfunction in respect of what a democracy should do,” she said.

In 1983, she recalled, the march for equality and against racism was appropriated by the Socialist Party, “which left its participants with the feeling of having been manipulated and of not having been given the place they sought in the political system”. Now, 30 years later, this sense of exclusion and of being let down is more relevant than ever.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter