Citing “the will to modernize our country and make it stronger”, President François Hollande presented his programme of territorial reforms in a lengthy statement published on June 3rd and which raised a storm of protest from the right-wing opposition and even among his own ranks, and more predictably among many local political ‘barons’ set to lose control over their regional fiefdoms as they are merged with those of others.

Mooted for many years but regularly never enacted, the reform is justified by a disorganized and multi-structured system of local political administration that is recognised to be ineffective and costly, and set against a backdrop of increasingly public dissatisfaction with the political establishment, both local and national.

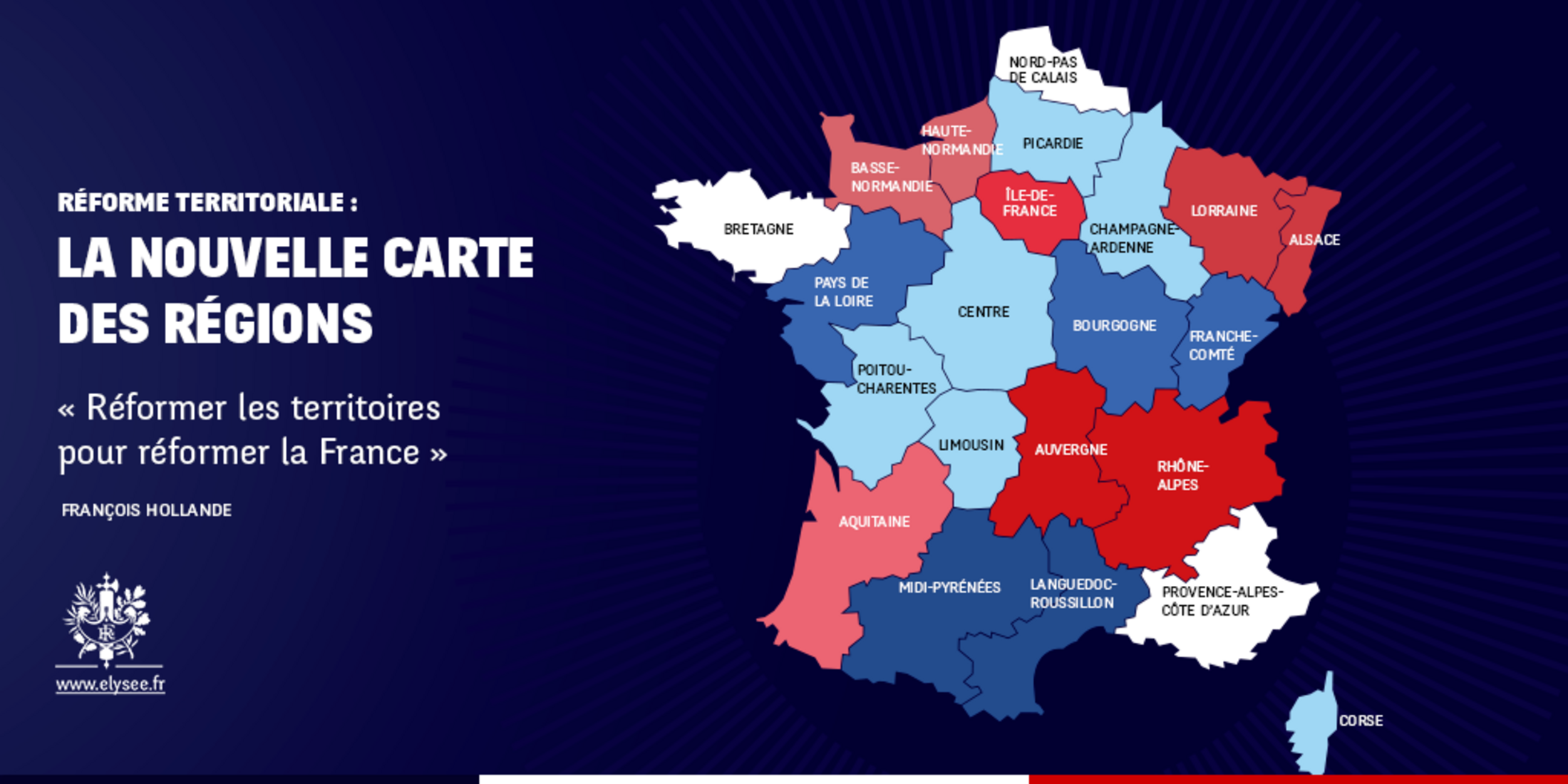

The most significant element of the reforms is a vast reduction in the number of regions in mainland France. “Their resources no longer correspond with their competencies, which themselves are no longer adapted to the development of the local economy,” wrote Hollande. “Therefore, to reinforce them, I propose bringing down their number from 22 to 14.”

The political assemblies of the regions are to be given greater local powers and, as a result, the general councils that govern the country’s patchwork of 101 départements, equivalent to counties, are to disappear by 2020. Lower down, the bodies that group together different municipalities for the joint administration of services like utilities and transport, called intercommunalités, will be enlarged so that each is responsible for a minimum total population of 20,000 instead of the current 5,000 inhabitants.

But right up until the last minute, Hollande was undecided on the exact number of new regions to be created. It was finally settled on the evening of June 2nd, just hours before Hollande’s statement and after a consultative meeting between Hollande, Prime Minister Manuel Valls, interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve and state reform and decentralisation minister Marylise Lebranchu, held at the Elysée Palace, the presidential office.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Evidence of this is a blank space in the text of Hollande’s statement as it was sent out to all of France’s provincial newspapers for publication the following day, June 3rd. “I therefore propose to bring down the number of regions from 22 to XX,” it initially read. Hollande’s opponents expressed outrage at the image of a president carving up the map of France on his own and according to last-minute deals made with local politicians.

Christian Jacob, an MP for the principal conservative opposition party, the UMP, and leader of the party’s parliamentary group, was scathing. “A president who at night, between 8p.m. and 9p.m., modifies the regions according to his phone calls, it’s unbelievable,” he said. “At 8p.m. the Pays de la Loire [region] was supposed to merge with the Poitou-Charentes [region], before afterwards being chucked over to the other side, it’s shambolic.”

Jean-Christophe Lagarde, a centre-right UDI party MP for the Seine-Saint-Denis département just north of Paris, and mayor of Drancy, the département’s second-largest town, echoed Jacob’s attack.“The map was invented on the corner of a table at the Elysée, made up last night at 8.40 p.m.,” he complained. “The method of force is calamitous, absurd and incoherent. All of this is the fruit of negotiations between Socialist Party barons.”

The political deals behind the makeup of the new regions was evoked by François de Rugy, an MP with the EELV Green party for the Loire-Atlantique region in west France “When we met with François Hollande, he spoke of a coming together of the Pays de la Loire [and] Centre [regions],” he said. “And he said that he will never manage to broker agreement between the socialists in Brittany and the [neighbouring] Pays de la Loire.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The proposed reduction of the number of regions, and which will be subject to parliamentary approval, involves merging most of their current borders with others. Under Hollande’s plan, Normandy will become one unique region, as opposed to the current two (Basse-Normandie and Haute-Normandie). Similarly, Alsace and Lorraine in the east will be merged, as also the southern Mediterranean regions of the Midi-Pyrénées and Languedoc-Roussillon, and the central Auvergne will be joined with the south-east Rhône-Alpes; Picardie, in the north, will become as one with its north-east neighbour Champagne-Ardenne, while the central Burgundy will merge with Franche-Comté, to its east. One of the most controversial mergers is that of the three current centre-west regions of Poitou-Charentes, the Centre and the Limousin.

For the French president, struggling with his own abysmal popularity ratings, his dismantling of a fossilised system that has escaped true structural reforms for decades is an opportunity to rejuvenate his political image. “It’s the biggest reform of this five-year presidency,” claimed Bernard Roman, a Socialist Party MP for the north-east Nord département (county). Roman underlined that as far back as 1982, under the socialist presidency of François Mitterrand, then-prime minister Pierre Mauroy wanted to reduce the number of French regions to 16. In the end, after lobbying by a number of powerful local socialist politicians eyeing the presidency of their regional councils, Mitterrand settled for a total of 22.

“The regional map dates from more than 60 years,” a current presidential office insider commented. “It’s now 30 years that we have wanted to modify it. There was the Mauroy report in 2000, the Balladur report in 2009 and the Raffarin report in 2013 [Editor’s note: officially-commissioned studies from three former French prime ministers recommending territorial reform]. All of them said the number of regions should be reduced. No-one did it. The president is the first to take action […] He, at least, has carried out the reform. It’s him indeed who is the boss, he’s shown that.”

'The king decided that there will be 14 regions'

Hollande’s territorial reform contrasts with the eagerness he has otherwise shown to appease local politicians during what are now his first two years in office. While he pushed through his reform to end the accumulation by politicians of several concurrent posts of office (such as being simultaneously a mayor and MP), he pushed back the introduction of the reform until 2017, the year when his current presidential term will end. Similarly, the bill of law to introduce greater transparency of politicians’ financial interests, hurriedly prepared following the revelations of budget minister Jérôme Cahuzac’s tax-evading foreign bank account, was watered-down in face of widespread political opposition led by the socialist president (Speaker) of the National Assembly, Claude Bartolone (an MP and himself a former president of the local council for the Seine-Saint-Denis département).

Last year, the first major plank of decentralisation reform, set out in a bill proposed by Marylise Lebranchu, Minister for the Reform of State and Decentralisation, was the target of numerous amendments to satisfy the interests of local politicians whose constituencies were threatened by the creation of larger, more powerful local councils. Hollande, meanwhile, has changed his views on decentralisation issues on several occasions, notably wavering over the future of France’s départements and over the mooted abolition of the ‘clause of general competence’ (la clause de compétence générale) - which allows local elected bodies to legally intervene in certain matters that are not strictly within their remit on condition that these are issues which have a clear consequence for the territory they preside over.

Hollande is himself a former mayor of Tulle, a town of some 15,000 inhabitants which is the administrative capital of the Corrèze département in central France, and was also the president of the Corrèze general council. Throughout his career he has built his political base through alliances with local politicians; his successful campaign in the Socialist Party primaries to elect the party’s candidate for the 2012 presidential elections was due in significant part to the support he received from powerful local socialist politicians. Socialist MP Pascal Cherki, who represents a Paris constituency, last year caused controversy within the Socialist Party - but also silent approbation from many - when he commented that “when you are the president of France, you are not a general councillor, you take measure of the situation and you change gear”.

While the reform presented by Hollande might offer the president at least a partial renewal of his image, his method of government is still far from representing a renewal of political practices.

After lobbying from defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and former prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, the north-west region of Brittany, and the centre-west region of Pays de la Loire are to remain unchanged, while what was seen as a logical merger of the north-east Nord-Pas-de-Calais region with that of its neighbour Picardy was excluded on the grounds that this would, on the basis of the results of recent elections, offer the far-right Front National party (FN) a significant regional power base in future local elections.

“We ask ourselves whether the result of the FN in the European elections doesn’t explain certain boundary changes,” commented Barbara Pompili, a Green party (EELV) MP for a constituency in Picardy and co-chair of the Green’s parliamentary group, shortly after last week’s announcement. “For them [the government], a merger between the Nord and Picardy, which was at one point envisaged, was to give the region to the FN. But you don’t combat the FN by electoral fiddling,” she said.

In a statement issued last week, the Communist Party denounced a reform that “is made at the cost of increased authoritarianism inherent to [France’s 54 year-old constitution of] the Fifth Republic and the putting in place of ever more technocratic powers that are sheltered from popular sovereignty”.

The manner in which the territorial reform was decided also came in for harsh criticism at a meeting of the socialist parliamentary group last week. “The king has decided that there will be 14 regions,” mocked Socialist Party MP Pouria Amirshahi. “This arbitrary and technocratic vision is intolerable,” added Amirshahi, who sits on the party’s Left.

Amirshahi and others have also denounced what they see as a budgetary approach to the reform of the regions, which government ministers have repeatedly argued will allow for public spending savings. Interviewed on France Inter radio on June 3rd, when the final details of the new organization of the regions were made public, André Vallini, junior minister for territorial reform, claimed the new number of regions would allow annual savings of between 12 billion euros and 25 billion euros out of the 250 billion euros in current annual spending by local authorities.

Vallini’s claim was contested by public finance experts on both the Right and the Left. “Merging regions will bring in nothing in the short term, save by closing down secondary schools and destroying rail tracks,” said socialist MP Olivier Dussopt, who sits on the parliamentary committee on constitutional, legislative and general administration laws. “But the reform will bring more efficiency and will clarify competencies.”

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse