On the evening of October 17th 1961, tens of thousands of Algerians held a defiant, pacific demonstration through the streets of Paris in protest at an overnight curfew imposed upon them earlier that month by the French capital’s police authorities.

It was organised by the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), just months before Algeria, a French colony since 1830, would finally achieve independence from France, ending 132 years of colonial rule and a bloody war that began in 1954.

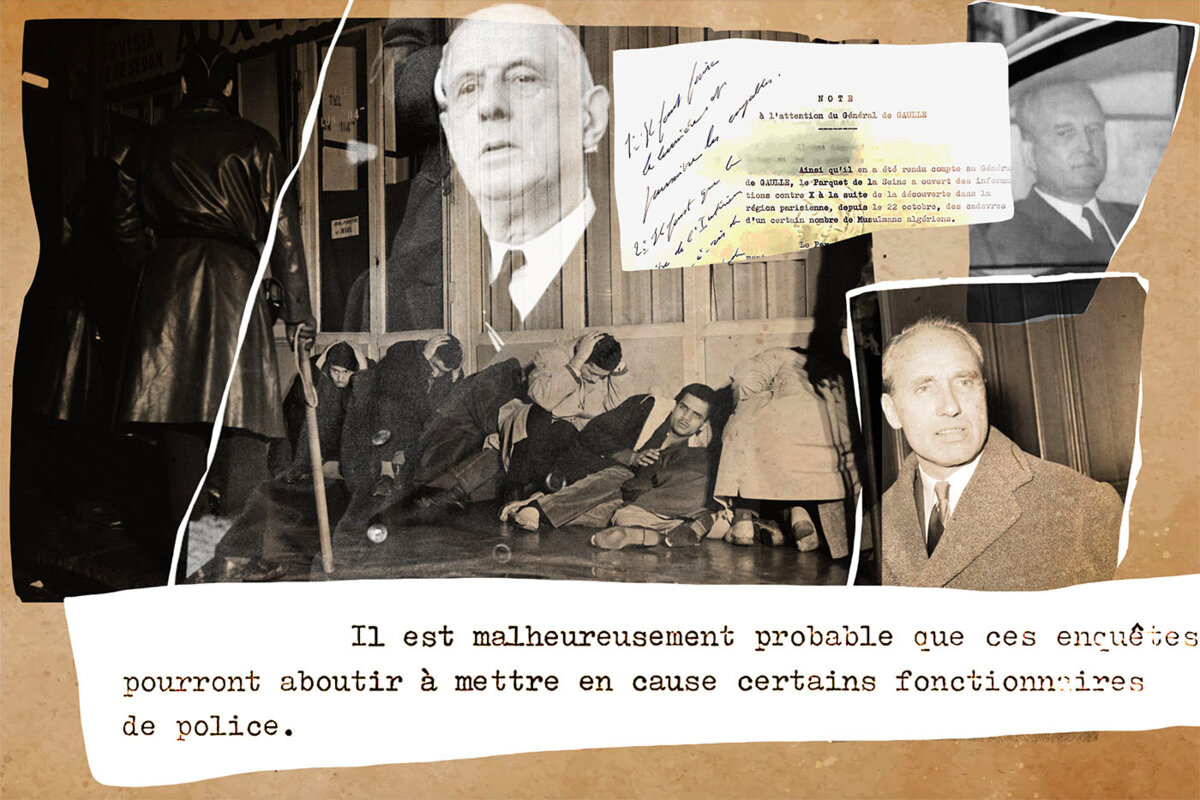

The then Paris police chief, Maurice Papon, who introduced the curfew on “Algerian workers”, had encouraged his officers to use brutality in dispersing the marchers, estimated to number around 30,000. The hate and tensions created by the seven-year independence war were at a flashpoint, fuelled by horrific violence committed in the North African country by both sides, and even among their own ranks.

In the weeks preceding the march, several police officers in the Paris region had been assassinated in attacks attributed to the FLN, while violent police repression against the estimated 180,000 local Algerian community, many of who were factory workers and labourers living, often with families, in insalubrious shanty towns around the capital, was notorious.

The death toll among the demonstrators from the extreme savagery of the police crackdown that October evening and through the night, when the marchers were blocked and broken up into smaller groups, has been estimated by several historians at around 200, many of them by drowning after being thrown into the River Seine, while an unknown number of others were injured, notably by baton charges.

The extent of the massacre was minimised by the French authorities, and for several decades access to the official archives relating to it, including police and judicial records, was prohibited. It would become largely expunged from public consciousness, amid a reluctance to confront the often-unpalatable events of the Algerian war.

It was not until the late 1990’s that a very partial amount of information from the records emerged, and it was only after 51 years of official silence that, in October 2012, then French president François Hollande issued a statement recognising the events: “On October 17th 1961, Algerians demonstrating for the right to independence were killed during a bloody repression,” it read. “France recognizes these events with lucidity. Fifty-one years after this tragedy, I pay homage to the memory of the victims.”

But mystery has continued to surround the true detail of the events of October 17th 1961, and in particular about what then French president Charles de Gaulle and senior government officials knew and how they reacted to the situation. In their widely acclaimed 2006 book of research into the massacre, Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror and Memory, British academics Jim House and Neil MacMaster write: “Little is known about either official or informal reactions to 17 October at the higher levels of government. De Gaulle and his ministers make virtually no reference to the events in their memoirs, while access to key documents of the Élysée, Matignon [editor’s note, the prime minister’s office] and the Interior Ministry remain closed.”

Now Mediapart has gained access to hitherto unpublished documents which prove that president de Gaulle had in fact been very quickly informed in detail about the October 17th events, including both about the responsibility of the police in the crimes and also the extent of the violent repression.

Mediapart’s discovery of the documents, which come from the records of the French presidential office, the Élysée Palace, was made possible following the recent and partial opening of access to relevant official archives by a government decree issued at the end of December 2021.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

A hand-written note by de Gaulle on a document from the Élysée archives shows how the then president, learning of the reality of the events, demanded that those responsible be punished, and that his interior minister, Roger Frey, intervene in face of the extreme danger posed by the unruly behaviour of the police.

In the end, no police officer was ever convicted of any crime committed that October night. Police chief Maurice Papon, who supervised and covered up the massacre, remained in his post, as did Frey, his ultimate boss. No-one would ever be brought to account for the killings and injuries, which would no doubt have been permanently erased from public memory were it not for the dogged determination of a few historians, archivists, journalists and rights militants to establish the truth.

Drownings, strangulations and shootings

Two documents in particular shed new light on the events. They are kept at the Pierrefitte-sur-Seine branch, north of Paris, of the French National Archives.

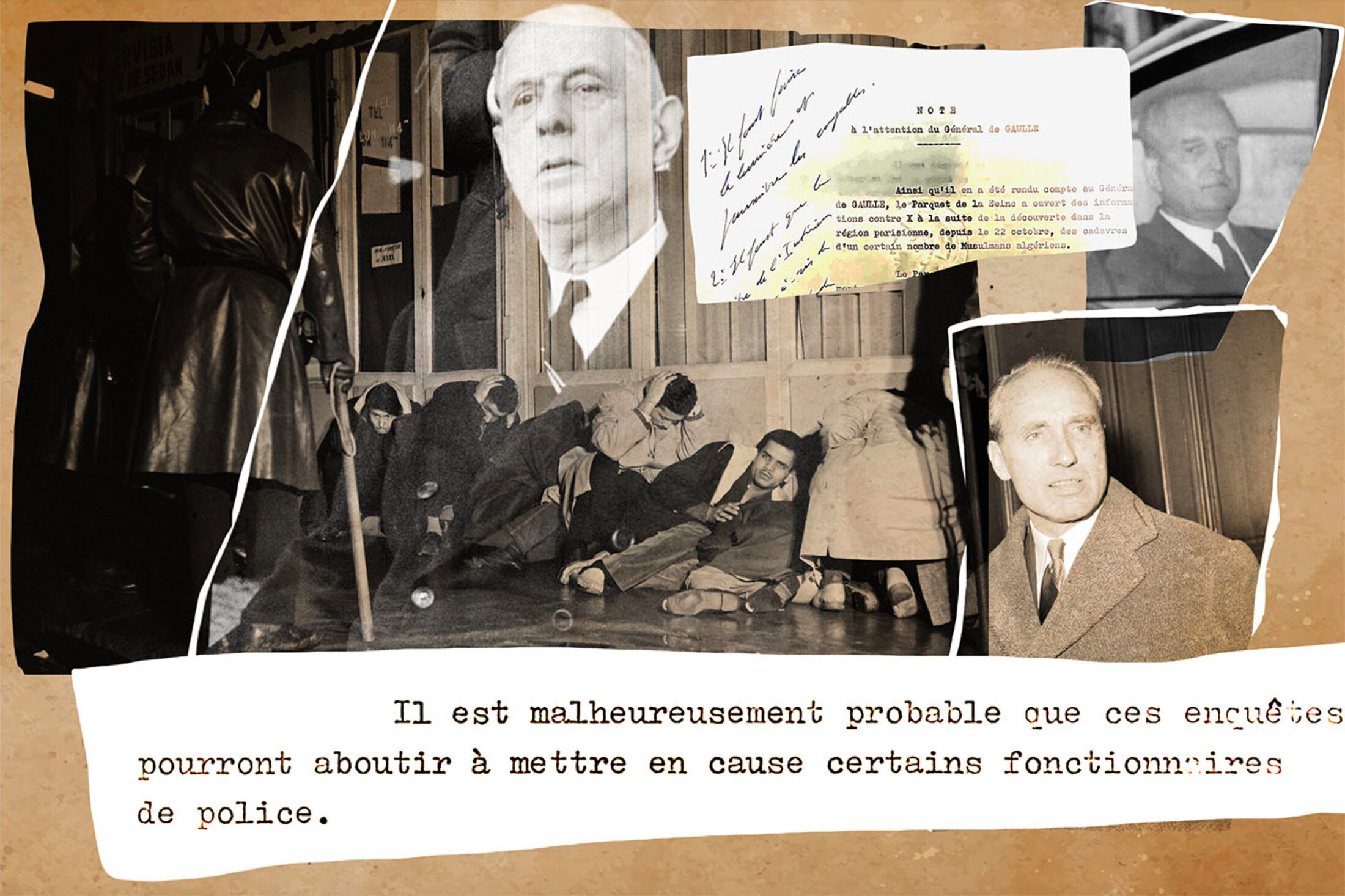

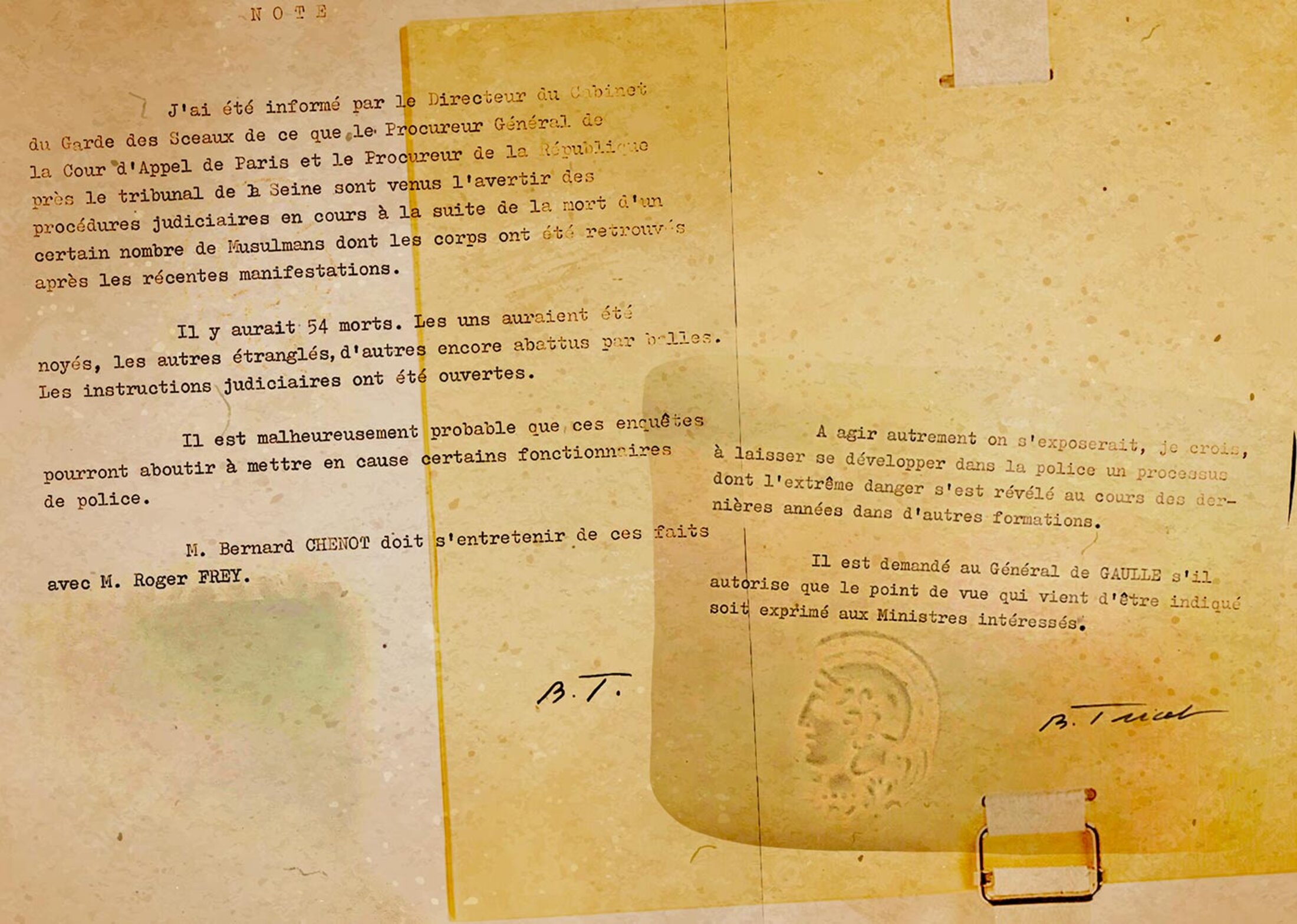

One of these is a report signed with the initials of Bernard Tricot, who in 1961 was de Gaulle’s advisor on Algerian affairs. Dated October 28th 1961, it reads: “I was informed by the director of the justice minister’s office that the Paris appeal court’s public prosecutor and the public prosecutor with the Seine lawcourts came to inform him of the ongoing judicial procedures following the deaths of a certain number of Muslims whose bodies were found after the recent demonstrations.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“There would be 54 dead,” Tricot continued, using the conditional tense in the original French to indicate a figure that was not thoroughly confirmed. “Some were drowned, others strangled, and [yet] others still killed by bullets. Judicial investigations have been opened. It is unfortunately probable that these investigations could lead to placing certain police officers in question.”

Tricot also noted that the justice minister, Bernard Chenot, who had been appointed to the post two months earlier, replacing Edmond Michelet who was considered by hardliners, like then prime minister Michel Debré, to be too conciliant towards the FLN, was to “discuss these events” with interior minister Roger Frey.

Until now, it was not known that one of de Gaulle’s most senior advisors had in fact established, 11 days after the events, an initial estimation of such a significant toll of the dead, and the manners in which they were murdered.

De Gaulle: “Light must be shone and proceedings brought”

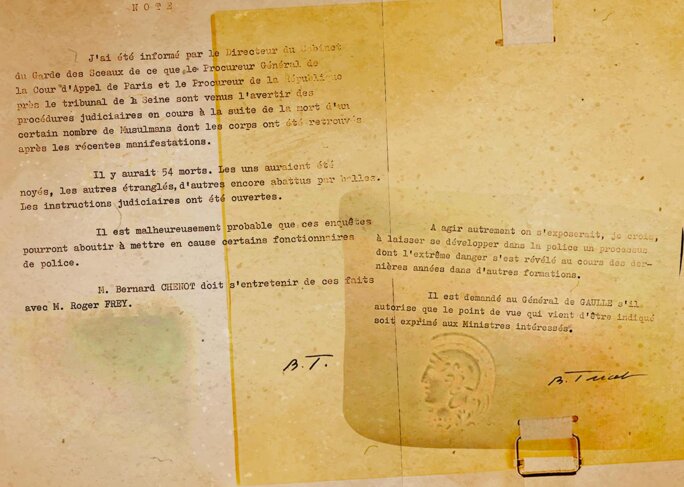

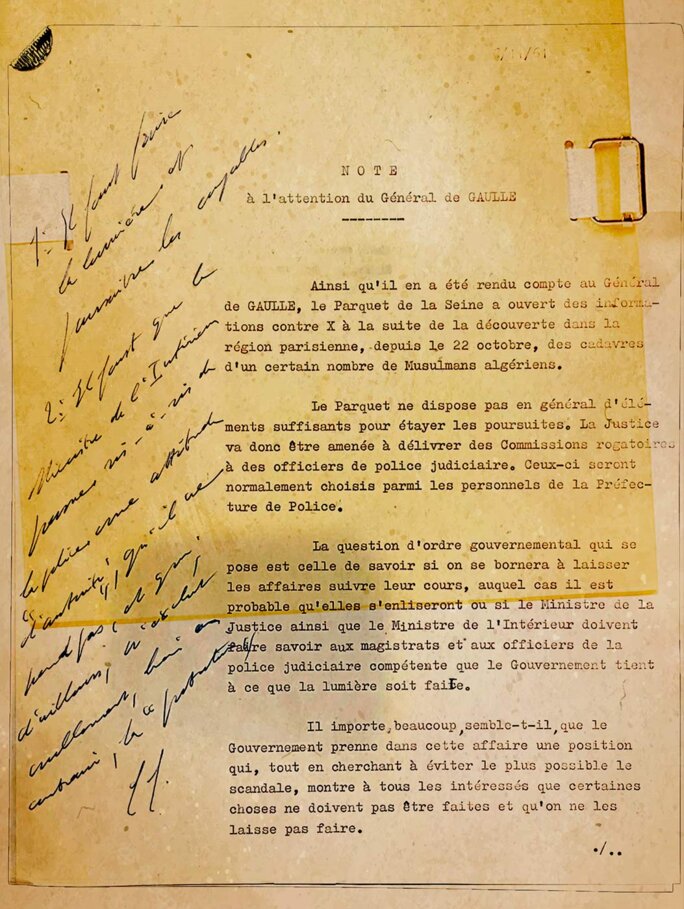

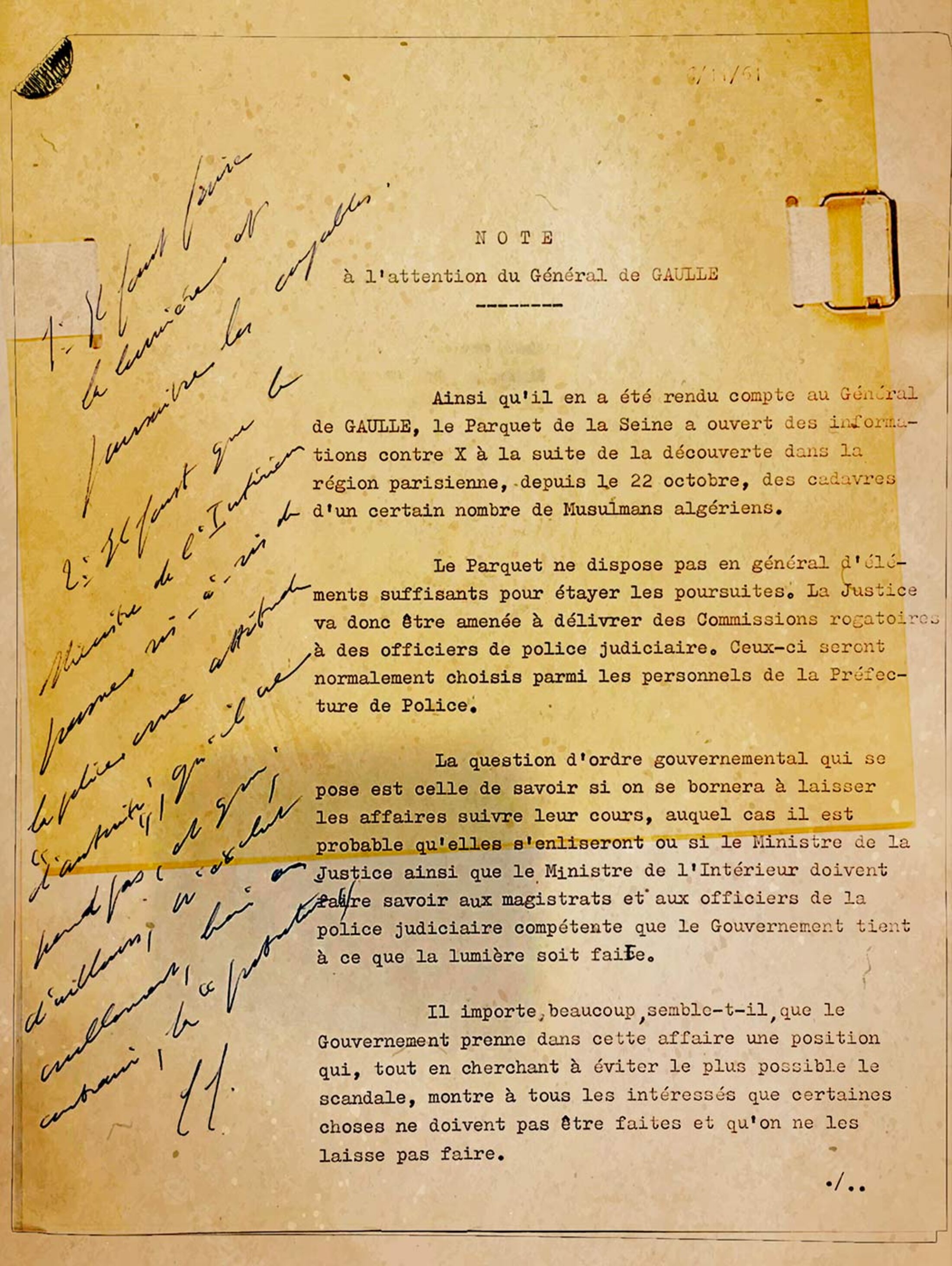

Another key document discovered by Mediapart is an advisory note again written by Tricot and addressed to de Gaulle, and upon which figures the hand-written response of the president. Dated November 6th 1961, it begins by referring to the opening of investigations by the public prosecution services “following the discovery in the Paris region, since October 22nd, of the corpses of a certain number of Algerian Muslims”.

Tricot informed De Gaulle that the prosecution services “do not in general have sufficient elements to support legal proceedings”, adding: “The question raised at a government level is that of knowing if one will content oneself with letting the affairs follow their course, in which case it is probable that they will become bogged down, or if the Minister of Justice and the Minister of the Interior should make known to the relevant magistrates and judicial police officers that the Government expects that the light be shone” on what happened.

“It is very important, it appears, that the government takes a position on this matter [and] which, while seeking as much as possible to avoid a scandal, shows to all those concerned that certain things should not be done, and that they will not be left to carry on. To act differently, we would be exposed, I believe, to allowing the development within the police of a process of which the extreme danger was revealed in other formations during the last few years,” continued Tricot, who by “other formations” was referring to dissident movements among the French armed forces, and notably the creation within their ranks in early 196 of the far-right Organisation de l’armée secrète (OAS), which opposed Algerian independence.

At the end of his advisory note, Tricot asked de Gaulle if he authorised “that the point of view that has just been outlined should be expressed to the ministers concerned”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

De Gaulle’s hand-written reply in blue ink, which he wrote in two parts on the blank lefthand column of the first page of the note, was unambiguous: “1) Light must be shone and proceedings [must be] brought against the guilty. 2) The Minister of the Interior must take an attitude of ‘authority’ towards the police, which he doesn’t, and which does not at all exclude, quite the opposite, ‘protection’.”

In the event, no-one would be punished, the Élysée would never make any comment on the subject and the interior minister kept his job. Police chief Maurice Papon would even succeed in establishing a police record of the events which contradicted the legal complaints filed by some of the relatives of the victims of the October 17th repression.

The scandalous manipulations of police chief Maurice Papon

Papon, who would eventually serve between 1978 and 1981 as budget minister, finally met his downfall in 1988. That year a French court sentenced him to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity for his role, as a civil servant with the collaborationist Vichy regime in German-occupied France between 1942 and 1944, in the deportation of more than 1,600 Jews from Bordeaux to Nazi concentration camps. He was released from prison in 2002 on health grounds and died in 2007 at the age of 96.

Among the archives of the French presidential office seen by Mediapart is a report signed by Papon, dated December 26th 1961, which was addressed to the French interior minister. It illustrates the extent of the manipulation by the police prefect to smother the scandal.

The report is entitled “Investigations led on the subject of complaints [filed] against the police following the demonstrations of October 17th 1961”. In it, Papon made every effort to discredit the complaints.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

He wrote that these “had been forwarded between October 30th and November 2nd by lawyers for the FLN”, adding that several of the complaints were lodged by people who “live in proximity of each other”.

“The concerted nature of these complaints thus easily appears: indeed, the complainants more or less made let it be understood that there had been soliciting by the lawyers,” he noted.

On the subject of those who did not present themselves before the police, Papon wrote: “The investigation can hardly leave any illusion about the validity of their complaints.” He added that among those who did present themselves to police, some were shown to have been telling “lies”, and that the accusations against the police were made in “obvious bad faith”.

Papon also reported that the murders of at least two Algerians, which the police had been accused of, were in fact carried out by operatives of the FLN, while concerning the physical assaults by police on demonstrators, their “importance has been inordinately exaggerated”.

He also addressed the subject of an article in the communist daily L’Humanité which reported that numerous Algerian demonstrators arrested on October 17th were taken to an internment camp in the western Paris suburb of Asnières, where they were subjected to physical abuse. “Nothing abnormal had been identified during their presence at the Asnières site,” he claimed. “[…] It plainly emerges from the investigation that this case was made up from beginning to end by the newspaper L’Humanité for political, general and local purposes.”

Another document from the Élysée archives also confirmed how, under Papon’s authority, everything was put in place to cover up the truth of what happened that October night. The document in question was an eight-page table of “comparisons between the alleged events and the results of the investigation”. It was filled with observations such as “a convenient complaint imposed by the FLN”, “mendacious complaint”, “dubious complaint”, “mendacious complaint organised by the FLN”, and “tardy and suspicious complaint”.

They were in sharp contrast to what was, already at the time, known about the crimes committed on October 17th 1961, as illustrated in a note written by Michel Massenet, a senior civil servant with the Council of State, France’s supreme court for administrative justice and which provides the government with legal advice. Massenet’s note was addressed to the Élysée in the autumn of 1961, but is not precisely dated. “One can in any case assert that the violence that was coldly manifested is without precedence in police history in France,” he said of the massacre.

“Innocent individuals killed by police”

Mediapart also discovered another archived Élysée document which reveals that the presidential office was also well aware, on top of the events of October 17th, of a recent wave of crimes by the police against Algerians in France, amid a number assassinations of officers by the FLN.

The note in question was not signed, but appears very likely to have been written by Benard Tricot because it is filed in the section of the archives containing his documents. Dated October 25th 1961, it was addressed to Geoffroy Chodron de Courcel, then chief of staff of the Élysée Palace, and depicts a chilling picture of state terror.

“Concerning the brutality and abuse which Algerian Muslims could have the victims of these recent days in Paris, I will put aside all that could have happened during the demonstrations or immediately afterwards,” it began. “In the same manner, there is no need to take into account all the gathered information of a vague or hypothetical character. By retaining only the precise facts that emanate from serious sources, it can be pointed out: that it happens that apparently innocent individuals, and in any case who have no threatening attitude, are killed by the forces of law and order.”

The note then lists a series of examples:

“ – In [the west Paris suburb of] Gennevilliers, on Thursday October 12th at 8.30pm, [at] 60, rue de Richelieu, in front of the boys’ school, a pupil from the French [-language] class, Ali Guérat, was shot dead. The head of the classes, Mr Vernet, was a witness to this murder.

– It happens that when Muslims are apprehended by police, the latter destroy their identity papers in front of them. While this is not a bloody event, it seems to me most serious. In a veritable assault, the police itself places men in an irregular [illegal] situation.

– Muslim hotels and shops have been ransacked by the police (a hotel in the 18th arrrondissement [Paris district], shops in [the west Paris suburb of] Nanterre,) apparently without the destruction caused being justified by the necessities of a sustained campaign, by measures of security or by the requirements of an investigation.

– Men apprehended after demonstrations and led to assembly points (Vincennes [south-east Paris suburb], the Porte de Versailles [on the southern Paris outskirt], a place called ‘the quarries, etc.) were brutalised, thrown down from the top of a staircase, beaten up.

– In certain places, the apprehended men were so crammed together that they had to remain upright not only during the day but also the night.”

The “missing link”

Mediapart presented copies of all the documents cited in this report to two French historians who have written about the events of October 17th 1961. They are Fabrice Riceputi, author of Ici on noya les Algériens (Here Algerians were drowned), published last year, and Gilles Manceron, who contributed to another book on the events (Le 17 octobre des Algériens), published in 2011, with a chapter entitled La Triple occultation d'un massacre (The triple eclipse of a massacre).

Fabrice Riceputi commented that the documents retrieved by Mediapart “constitute a sort of missing link in the historiography of this tragic event”. He said that their contents showed that, at the time, the French presidential office “knows that the version of events that was fiercely supported in public by its prime minister, Michel Debré, the minister of the interior, Roger Frey, and the police prefect, Maurice Papon, and largely relayed by the wide-public press, is mendacious”.

Riceputi underlined that the Paris police headquarters, the prefecture de police, maintained as of October 18th that there had been but two deaths of “French Muslims of Algeria”, and one non-Algerian French national, in the “violent” demonstration organised by Algerians, and that the police were irreproachable. “It should be noted that the reprobation expressed by de Gaulle in these archives, while it has the merit of being made known, never translated itself into a public calling into question of this version that for decades remained official,” he said.

“Roger Frey and Maurice Papon would again, under the authority of de Gaulle, be responsible for another police slaughter,” added Riceputi, “that of the Charonne metro station [in Paris] which caused nine deaths on February 8th 1962 during an anti-OAS demonstration. And both of them would be kept in their posts by de Gaulle for five more years, up until 1967.”

Gilles Manceron said the documents obtained by Mediapart “confirm that general de Gaulle, who had removed from the prime minister all authority over Algerian policy, had left the latter, at his request, responsibility for ‘maintaining order’ in France, and that he had disapproved of the manner in which he struck out at the FLN and Algerian emigration in 1961”.

Manceron added that the reason de Gaulle finally decided against insisting on punishments for those responsible for the massacre, which the archived documents show he had initially been in favour of, was “in order to avoid that his [ruling political] majority would fracture, and that a part of it reject him”.

In March 1962, any lingering doubts about whether those responsible for the horrific events of October 17th 1961 might one day face prosecution, as had been encouraged by the French president, were forever dispelled by the promulgation of a law that introduced an amnesty for the perpetrators of any crimes committed “in relation with the events in Algeria”.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------