Faced with the looming climate disaster, companies are keen to highlight the efforts they are making to cut their emissions of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas. France's postal service La Poste, which is 100% publicly-owned – the state investment bank Caisse des Dépôts has a 66% stake and the French state 34% - is no exception. Indeed, in its public utterances the postal service has been very bullish on the issue, claiming it is the “first postal operation to be 100% carbon neutral”, thanks in particular to its fleet of electric vehicles.

La Poste also takes part in 'Green Postal Day', an international initiative in which companies who deliver letters and parcels commit to reducing their carbon footprint. La Poste has set itself the target of reducing its own emission of greenhouse gases by 25% between now and 2025, and in September 2020 it proudly announced that it had cut its emissions by 22% compared with 2013.

In mid-October this year the Banque Postale, the postal bank 100% owned by La Poste, announced that it wants to end all involvement with fossil fuels by 2030; it has made a commitment to stop funding energy projects based on oil or gas, to stop supplying financial services to companies that run such projects, and to end investments in such firms.

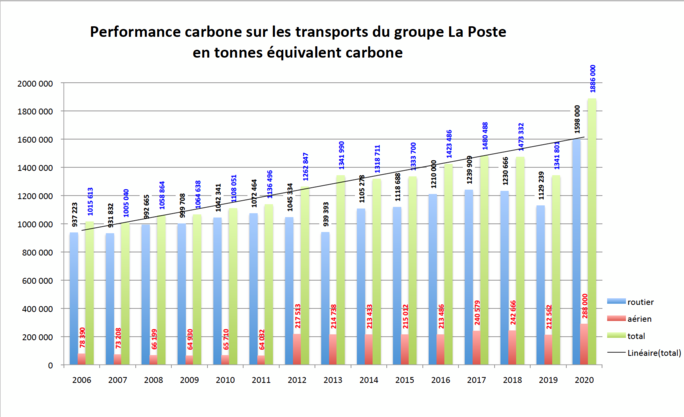

But in reality La Poste's carbon performance is significantly less virtuous when it comes to its core activity: collecting and delivering the mail. In 2020 the group's postal activities emitted 1.9 million tonnes of CO2, a rise of 40% on the previous year, according to its own internal report. This increase is totally at odds with its public commitments.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Overall, in 2020 the group produced 2.3 million tonnes of CO2, when emissions from its buildings are also taken into account. By way of comparison the water and waste group Veolia said it produced 40.8 million tonnes of CO2 in 2020 (across the three different types or 'scopes' of emissions: direct, energy purchase and indirect) while energy giant EDF produced 25 million tonnes in direct emissions.

Questioned by Mediapart, La Poste said the volumes of CO2 it emitted last year were the automatic consequence of the “increase in the volume of parcels and the external growth” of the group, as well as the growth in the number of deliveries linked to the Covid pandemic. But it said that the level of emissions “per delivered parcel” was down; by 5% for its DPD-Geopost international express service for parcels under 30kg, and by 17% for its Colissimo service for deliveries to private homes. Meanwhile “to compensate”, its “investments” went up in line with these emission increases, it said, referring to the controversial carbon credit purchase scheme, in which a company's own emissions are offset by ploughing money into the restoration of ecosystems, in particular in poorer nations.

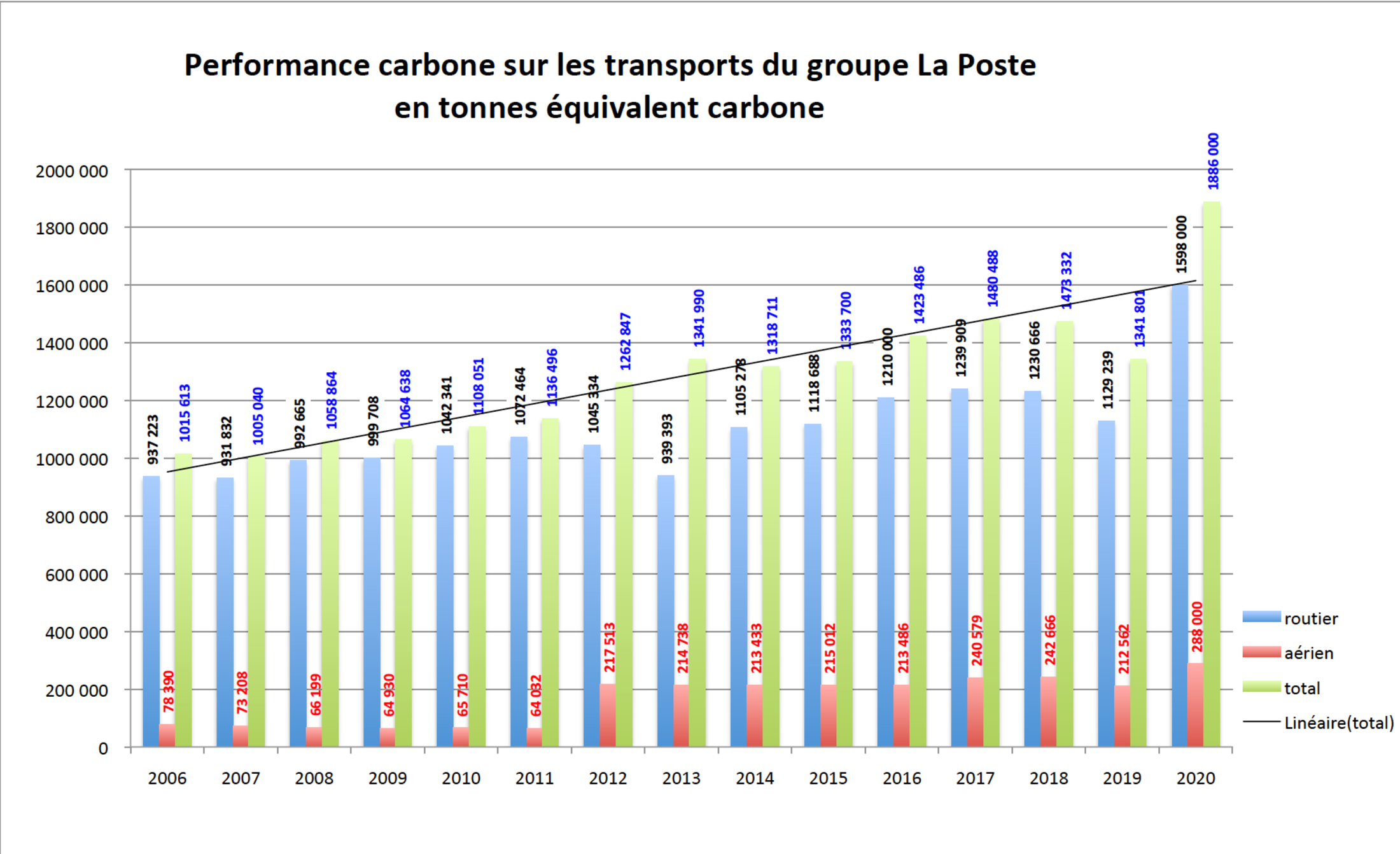

However, the problem is not a one-off as the group's statement seems to suggest. Compiling data from transport emissions for the whole group since 2006 shows that there has been a spectacular 46% increase in the production of CO2 by the group. In other words, over the past 15 years La Poste has been emitting more and more greenhouse gases, contrary to its official objectives and its own statements.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The explanation for this lies in the fact that La Poste only uses lorries and aircraft to carry its letters over long distances, and not trains. Yet these forms of transport emit a lot more CO2 than rail.

La Poste's national and international operations include what are called “universal service” missions. These are the collection and delivery of mail six days a week over the whole of the country, of letters and parcels up to 30kg, plus express delivery parcels. La Poste is, incidentally, now the second largest postal group in Europe; for example, in 2019 it bought the main Italian express delivery service BRT.

While the “final kilometre” of the post office's universal service is carried out using electric vehicles (it has close to 40,000 such cars and bikes), all the rest of the mail's journey is by air and road. And since the start of the 2000s La Poste has closed its sorting offices in the country's départements or counties, of which there were 120 in 2003. They have been replaced by around 15 large centralised sorting offices.

The result of this restructuring has been an increase in the number of kilometres the mail has to travel. For example, a letter sent from the north of Paris to somewhere else in the capital has to go via the town of Gonesse, which is 16 kilometres to the north of the city. Meanwhile a letter sent from Confolens in the Charente département in the south-west of France to the departmental capital Angoulême 60km away has to go via Bordeaux, which is 200km to the south. These letters are carried by lorries that produce carbon dioxide and pollution on the roads. “These journeys make no sense, unlike basing its activities locally again,” said Nicolas Galepides, from the trade union SUD PTT which represents many postal workers. He said: “La Poste's sustainable development strategy has never worked towards alternatives to only using the roads or the air for mail transport.”

The French postal group itself says that, on the contrary, the “sharing and consolidation [editor's note, of deliveries] allows for a reduction in the number of lorries on the roads”. However, it did not address the point that a greater number of kilometres are travelled. Between now and 2025 the group has set a series of objectives to reduce the carbon impact of its road transport: optimising the storage of parcels in lorry trailers, limiting the number of return trips with empty lorries, converting 25% of the transport fleet into natural gas vehicles (NGV), using natural gas or methane which is less polluting than diesel.

The focus on parcels reflects recent consumer trends; while businesses are sending fewer and fewer letters, the market in sending parcels is booming, boosted by online purchases. In 2019 a total of 1.3 billion objects were delivered in France or exported.

La Poste insists that it is “studying all the transport methods that allow [us] to deliver to [our] customers while offering a better environmental performance”, in particular thanks to its “green fleet”. With its more than 38,000 electric vehicles this fleet is “one of the biggest in the world”, says the group.

Yet La Poste has abandoned its past attempts to carry the mail by high-speed TGV trains, even though this was once considered to be an alternative to using aircraft. In 2007 the group sold its subsidiary Europ Airpost (formerly Aérospostale) which used 15 planes for express freight deliveries. At the time La Poste's management wanted to shift to deliveries via high-speed rail services, using night trains. This plan was recorded in the minutes of a board meeting held on November 8th 2007, which have been seen by Mediapart. The aim was first to use rail to replace air transport, and then to use it instead of road transport. A joint company was created with rail operator SNCF and called Fret GV.

In January 2008, during another board meeting, La Poste's managing director, Raymond Redding, explained that the “direction taken is aimed at showing the possible operational synergy between the reduction of carbon emissions and the improvement of economic performance”.

But Fret GV's business never took off. In 2007 its turnover reached 200,000 euros, which was more or less its operating costs. At the end of 2009 a leaflet from the SUD PTT trade union expressed concern about the subsidiary's “sluggish” performance. Seven years later La Poste announced the end of its high-speed train postal operations, which had become loss-making as volumes of mail decreased.

The group tried to keep using the railways for certain mail; a multimodal hub was established at Bonneuil-sur-Marne, south-east of Paris. Previously lower priority mail was collected and distributed by lorries. Instead, this mail was sent from the new site to Bordeaux, Toulouse and Marseille in the south of the country by rail. But this new rail activity was also stopped. So having abandoned trains, and having no planes of its own any more, La Poste now pays private companies to use aircraft. The group thus faces a double loss: environmental and economic. Why did it abandon carrying parcels and letters by rail? “Rail freight did not allow La Poste to carry out its 24-hour services, there was an issue about meeting deadlines,” the group said.

La Poste's setbacks over the rail services and the subsequent impact on CO2 emissions and thus the climate are even more concerning given that the delivery of the mail is a public service. Critics might be forgiven for wondering about the state's strategic vision in relation to this issue.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter