Though staff at Sanofi have tried hard to find an explanation, they still do not understand. Or rather, they understand all too well the direction taken by the giant French pharmaceutical group. After the setback in its plans for a Covid-19 vaccine – put back to the end of 2021 at best – it seemed the obvious time for management at the multinational to query the wisdom of its decisions about the future role of essential research. But there was to be no change of plan.

On January 28th 2021 executives at the group's research arm Sanofi Recherche et Développement confirmed at an internal meeting of its works, health and safety committee that it was shedding 364 jobs in France. This move will especially hit the group's unit in Strasbourg in north-east France whose work is set to be transferred to the Paris region.

The decision is part of a wider programme of change that was announced in July 2020. The group plans to get rid of 1,700 posts in Europe, a thousand of them in France, over three years. “But that is only part of Project Pluto [editor's note, the name for the group's business plan],” warned Jean-Louis Perrin, an official for the CGT trade union at Sanofi's centre at Montpellier in southern France. “Sanofi is in the process of deindustrializing itself. All the pharmaceutical production [editor's note, where the active ingredients for many basic medicines are made] is earmarked to disappear from the group. The sites at Sisteron, Elbeuf, Vertolaye, [editor's note, in France] Brindisi (Italy), Frankfort (Germany), Haverhill (United Kingdom)and Újpest (Hungary) are destined to leave the group [editor's note, to move into a new standalone company]. In all, that represents 3,500 jobs.”

How can the French government let this happen? Faced with the shock of the twin setbacks at Sanofi and the Pasteur Institute – both supposed to be leading global figures in vaccines but at the moment unable to produce a vaccine against Covid-19 between them – politicians have started to ask questions.

The failure of these two groups, who are often held up as examples of the “excellence of French research, is seen as further proof of how the country has fallen behind. In this context the announcement of new job losses in research centres at Sanofi – which has already shed 3,000 jobs in ten years in France – seems incomprehensible.

“It's a disgrace for a group such as Sanofi and a humiliation for France not to be able to get a vaccine on the market,” said Fabien Roussel, national secretary of the French Communist Party (PCF). He pointed out that over the last decade Sanofi has received 150 million euros a year in tax credit aimed at promoting research.

As German publication Der Spiegel, has pointed out, there is also the issue of how the Élysée came to support Sanofi being part of the European Union plan to buy vaccines amid circumstances that remain unclear. As an investigation by Le Monde has shown, Sanofi did not meet any of the eligibility criteria for that plan. Yet the group received upfront funding of 324 million euros after the EU ordered 300 million vaccine doses.

Even Members of Parliament in the ruling La République en Marche (LREM), who have constantly jeered at interventions on the issue by MP François Ruffin from the radical left La France Insoumise (LFI), are no longer laughing. As a journalist and MP Ruffin was one of the first to raise the alarm about the Sanofi situation. “It's a sign of decline in our country and that decline is unacceptable,” said François Bayrou, founder of the centrist MoDem group who are allies of LREM, and who is now the country's High Commissioner for forward planning. Meanwhile there has been a deafening silence from the government.

Within the group itself and in the wider scientific community the criticism is even more biting. While everyone accepts there is always an element of luck and chance in research, and that setbacks and dead-ends are part of the innovation process, they still question Sanofi's strategy.

“I don't understand why Sanofi chose to develop a vaccine based on recombinant proteins, because that means you have to remake the vaccine each time the virus mutates. Yet as we have seen, a virus mutates,” said Jean – not his real name – a researcher at the French health and medical research institute Inserm. Fabien Mallet, who is a CGT trade union official at Sanofi, said: “That's a good question. I think they took the least risky, least expensive route.”

But it was the belated and laborious explanations from Sanofi's management which outraged the group's researchers even more. “They explained that they made a mistake over the concentration of the reagent. How can you reach the stage of doing human trials without having checked the concentrations of the products? It's ABC stuff in the profession. It proves that they lost control of everything. The whole ecosystem was affected,” said Sandrine Caristan, a researcher at the Sanofi centre in Montpellier and a representative of the trade union Sud Chimie. The Inserm scientist Jean said: “It's incomprehensible. They they to have forgotten all scientific procedures.”

Sanofi did not respond directly to this criticism. The group told Mediapart that the “strategy to pursue was identified and the problem resolved”. It added: “We are confident and firmly resolved to develop a safe and effective vaccine against Covid-19.”

The government appears happy with these responses and has played down the situation. Yet an entire industrial sector is in the process of falling to pieces in front of our eyes at the very time the epidemic shows how vital this sector is. “It's been a long time coming. We're paying the price for endemic delays,” said Frédéric Genevrier, co-founder of the research analysts OFG Recherche.

It is the price of thirty years in which industrial policy was abandoned while at the same time many of the state's capabilities have simply disappeared. It is also the result of thirty years in which sacrifices were imposed on public research, which was looked upon simply as excess expenditure. The current situation also stems from a belief that our industrial 'national champions', who are now in the private sector, know how to react to events far better than the state.

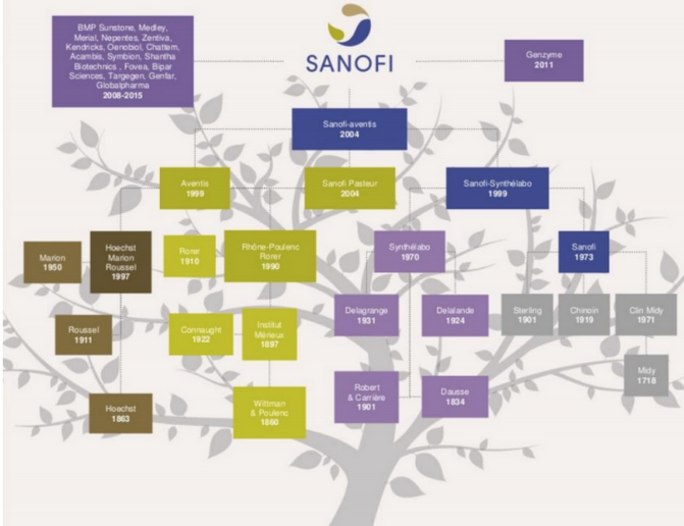

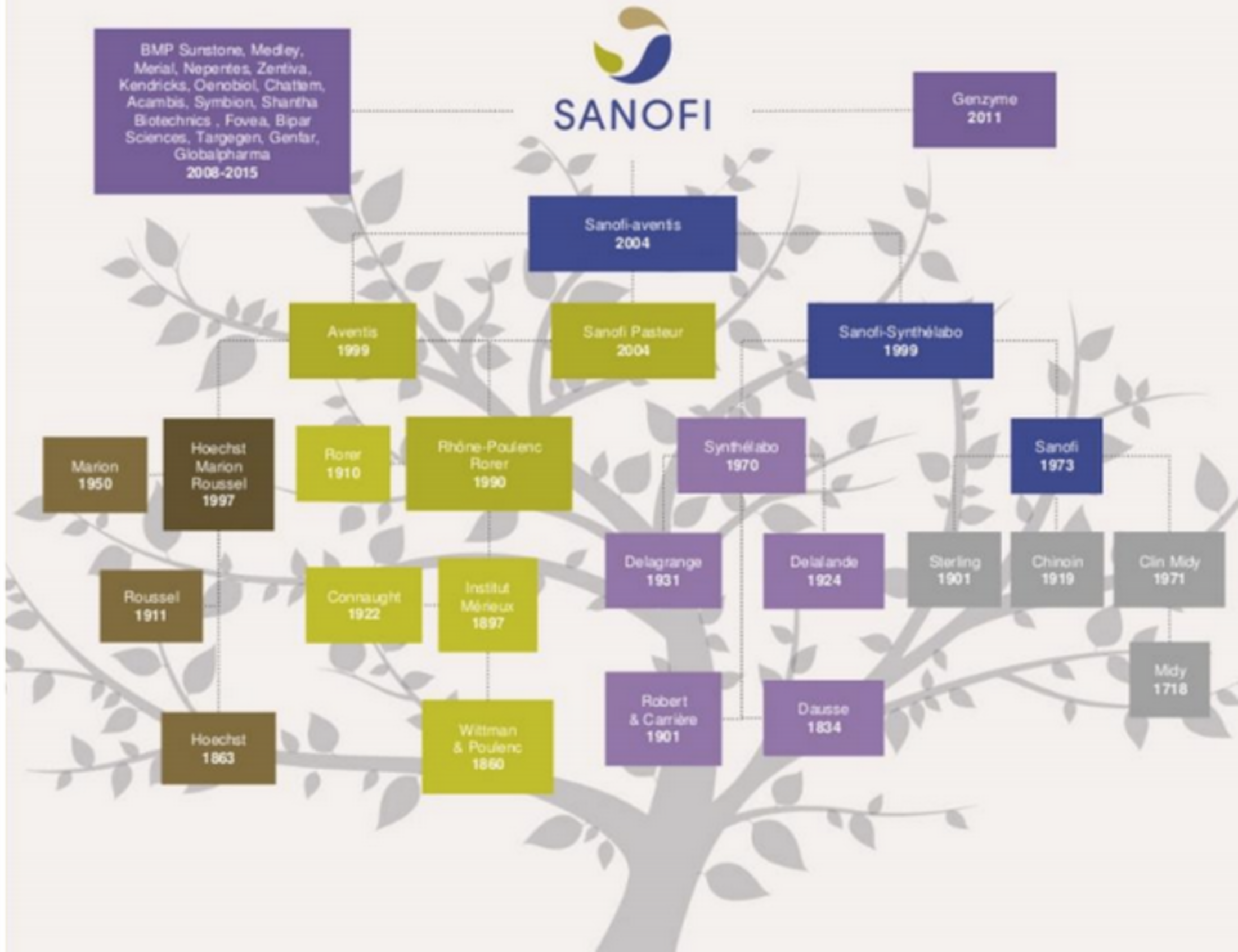

Sanofi was formed in 2004 when a company called Sanofi-Synthélabo merged with Aventis and was renamed Sanofi-Aventis. Aventis itself was the result of around 40 years of mergers between nearly all the main players in the French pharmaceutical industry that had sprung up since the start of the 19th century. When the government of President François Mitterrand nationalised the sector in 1981 three big names dominated the market. These were: Rhône-Poulenc, a major chemicals, agrichemicals and pharmaceutical company which was the biggest player in the sector; Sanofi, which was created in 1973 within the Elf oil group (now called Total); and Roussel-Uclaf, a specialist in penicillin who had links with the German pharmaceutical group Hoechst.

These groups then turned their attention to the various small rival laboratories around the country and started buying up or gaining a controlling stake in them. Successive governments backed this move, which looked on these financial operations as a consolidation of “French excellence”.

“It was the regulations that led to Big Pharma. The clinical trials were more and more expensive, you needed financial clout to be able to carry them out. On their own the small laboratories could not have managed,” said Loïk Le Floch-Prigent, who as chief executive of Rhône-Poulenc (1982-1986) and then Elf (1989-1993) was behind many of these mergers.

Big Pharma, French-style

Rhône-Poulenc accelerated this process in 1991 - before it was even privatised - when it bought the American laboratory Rorer. It was the start of a major transformation at the group which decided to focus on pharmaceuticals and abandon its other sectors. The chemicals business was hived off to become Rhodia – amid a major scandal in 1998 - which was taken over in 2011 by a Belgian chemical group. The agrichemicals side of the group was let go over time.

In 1999 Rhône-Poulenc itself merged with the German group Hoechst, which also enabled it to get control of Roussel-Uclaf. This new group then took the name Aventis. This merger occurred at the same time as the Düsseldorf-based telecoms conglomerate Mannesmann was taken over by British firm Vodafone, a move which caused a shock in Germany. German business owners and the government there vowed that this kind of operation would never be allowed to happen again. Together they worked to protect “Germany PLC” from corporate predators, to ensure no domestic groups could again fall under foreign control.

In France, by contrast, the government and the business world were jubilant. They were delighted that the idea of a national champion had been exported; a European leader in pharmaceuticals was being created. In return it was only right, the argument went, to allow foreign groups to take control of French groups in order to create world-beating groups. Perhaps the hope was that this would lead to a form of industrial trickle-down effect, which would spread through the economy. This approach, however, overlooked the positive effect that keeping a local industry in an area can have on the rest of society.

Having let a number of industrial firms go - Arcelor, Pechiney, Technip, Lafarge and Alstom just to name the most high-profile – the French government suddenly discovered that industry's contribution to annual GDP had fallen to 11%. Only Cyprus and Luxembourg had lower levels.

At the same time as Aventis was created, Sanofi was merging with Synthélabo, one of the last great French laboratories. But the head to head competition between the two large French pharmaceutical groups did not last long. In 2004 Sanofi and Aventis merged with the encouragement – almost at the demand of – Nicolas Sarkozy, who was then minister of finance.

Everyone saluted the move as it seemed to support the idea that France needed a pharmaceutical 'national champion' to compete against international competition. France now had its 'Big Pharma' group, able to fight it out with Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Roche and others.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Close to 80% of French pharmaceutical activity was now brought together in the new group. But the French government insisted that the situation was under control. The two main shareholders of the new group were oil firm Total and cosmetics firm L'Oréal who between them controlled more than 30% of its capital. Sanofi-Aventis, which soon became just Sanofi, was run by Jean-François Dehecq, who had founded Sanofi in 1973. The French government insisted he was a safe pair of hands who had always defended companies maintaining their roots in France, and that the group was secure in the private sector.

“I don't know why we still consider Sanofi as a French group,” said Frédéric Genevrier of OFG Recherche. For the protection that was envisaged at the time of the merger creating Sanofi-Aventis turned out to be flimsy. Total sold all its stake in the group while L'Oréal held on to just 9.4% of the pharmaceutical firm's capital. The state-owned public investment body the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations held a stake of barely 5%, while the rest of the capital was owned by the market. The asset management firm BlackRock, for example, had a 5.9% stake.

Just one person has helped maintain the illusion that the group remains a “French champion”: Serge Weinberg. He has been chair of Sanofi since 2010 while continuing to watch over his own investment firm Weinberg Capital Partners, which he set up after working for the luxury goods group Pinault.

Opinions are divided about Serge Weinberg's role in the group. “I think Weinberg has a very important role. CEOs move on and he remains. He is there to keep an eye on the commitments made to shareholders,” said Marion Lassac, an official at trade union Sud Chimie. However, the CGT trade union's Fabien Mallet insists: “Weinberg is like the Queen of England. He's just there to keep the French happy, to make sure it's okay with the public authorities.”

It seems that Serge Weinberg fulfills his role in relation to the French government to perfection. “A few months ago Serge Weinberg assured the Élysée that would be ready in March,” said someone familiar with the situation. This assurance could explain why France then pushed Sanofi's case with the European Union.

Serge Weinberg certainly has close connections with the man in charge at the Élysée. He was a member of the 2007-2008 commission on freeing up the French economy headed by economic Jacques Attali, of which Emmanuel Macron was the permanent secretary. It was Weinberg and Jacques Attali who introduced Macron to the Rothschild merchant bank in France. He then continued to keep an eye out for his protégé, and in particular backed him as deputy chief of staff at the Elysée in 2012 under President François Hollande.

The American model

“The United States represents the reference point in the pharmaceutical sector. Along with finance it's the sector where the salaries are highest,” said Frédéric Genevrier. The result of this is that financiers gradually took the pharmaceutical world and gained ascendancy over researchers and scientists.

A new model, that of Big Pharma, emerged. These huge groups, that had a near-monopoly in some areas of medicines, became dominant in the sector. They became financial rather than industrial groups, juggling billions of dollars, shares and patents. Rather than carrying out the work themselves they buy start-ups, take over their patents and develop them. The dream is always to come up with a blockbuster; the medicine that produces a turnover of more than a billion dollars.

The French pharmaceutical groups were quickly lured by the siren calls of the American approach. Indeed, as Loïk Le Floch-Prigent said, they wanted to be “top of the class”.

As far as staff at Sanofi are concerned, the big change came in 2009 after Jean-François Dehecq left as CEO. “It wasn't the idyllic period that some now speak regretfully about. But he believed in research. He wanted to develop activity in France,” said Sud Chimie's Marion Lassac. The board of directors then appointed Christopher Viehbacher, former finance directer at GlaxoSmithKline, to replace him. The mention of his name still causes a shudder among some people in the group.

His first words were directed at the group's shareholders: Viehbacher swore he would do all he could to raise the stock price. “Shareholder value” became the main objective of Sanofi's entire strategy. Since 2000 the level of dividend paid out by Sanofi has grown by more than 600%. In 2020 Sanofi distributed 4 billion euros in dividends, which is more than its net income of 2.8 billion euros in 2019.

'Shareholder value' and 'aligning executives with the interests of shareholders'

A policy of “aligning the interests of executives with the interests of shareholders” naturally immediately followed the changes at Sanofi. Even before taking up his duties as chief executive officer in 2009, Christopher Viehbacher picked up a golden hello of 2.2 million euros accompanied by a ten year bonus for his pension pot. When he was fired in 2014 he was given a golden parachute payment of 4.4 million euros. His package, including salary and bonuses, came to a total of 12 million euros.

His successor, Olivier Brandicourt, had to make do with a little less: he left with 2 million euros in pay plus performance-related stocks and shares worth around 5 million euros, a total package of 7 million euros. Paul Hudson, who succeeded him in mid-2019, is due the equivalent of a golden parachute, payable over two years, of 3.7 million euros and his pay is around 2 million euros.

In the criteria used to calculate the performance-related part of executives' pay at the group, the innovation of new products only counts for 10% of the amount, with the portfolio of group products making up another 12.5%. However, the group's financial results represent 26.7% of performance pay and overhauling the group's operations a further 15%. This shows that the objectives given to the chief executive by the board of directors are first and foremost financial.

Public research in disarray

“In the American model you certainly have Big Pharma, the financialisation of the sector and the purchase of start-ups, but there is another component: public research,” said Paul – not his real name – a researcher at the French public research body the CEA. “There's a whole ecosystem of public research, private research, small and medium-sized companies, development centres and big groups supporting each other and pooling their resources. All the big pharmaceutical groups work in the high-performing American academic research centres, which have lots of resources. These are centres of excellence for the industry.”

And though it is private and heavily financed, the pharmaceutical sector in the United States also gets a massive amount of public aid, grants and support. Various American agencies put up billions of dollars to help the development of certain medicines by private laboratories. Universities and research centres are actively involved in these projects.

But the situation in Europe, and especially in France, is nothing like that. “Have you heard research spoken about once in the last ten years?” asks Bernard Ésambert, former industrial advisor to the late President Georges Pompidou – who was prime minister from 1962 to 1968 and president from 1969 to 1974 - and one of the people behind the great industrial programmes of the Pompidou period. “Where are the engineers, the scientists in minsters' private offices? We created a tax break for research without any encouragement and without directing it, thinking that we'd solved the problem once and for all. But there's no desire, no guiding principle, no medium-term policy.”

To support his argument Bernard Ésambert points to the example of South Korea “a country comparable in size to France”. South Korea devotes more than 3% of its GDP to research and aims to exceed 3.5%. “And it has big electronics groups,” he said.

For years, spending on research in France has stagnated or even reduced, across all sectors. This is a dangerous development according to economists Margaret Kyle and Anne Perrot, authors of a report on pharmaceutical innovation for the Conseil d’Analyse Économique (CAE), an independent body that reports to the prime minister, published on January 26th 2020.

While Germany spends “3% of its GDP on research” France spends “just over 2% of which only 18% is dedicated to life sciences and health,” the report's authors note. They continue: “Public funding of research and development on health is also more than twice as low as in Germany and went down by 28% between 2011 and 2018, while over the same period it went up by 11% in Germany and by 16% in the United Kingdom.”

These figures reflect a deep conviction that has taken hold within the upper reaches of the French state; it is not down to the state to have ideas and a long-term vision that might distort the market place, which is seen as much better at choosing where to invest and which paths to follow.

Moreover, both France's Finance Ministry and the country's public accounts watchdog the Cour des Comptes see public research as a costly money pit, a world of sleepy civil servants. On top of this there have been successive reforms in research, one of the major recommendations of the Attali Commission. Among other things this has imposed the need for project tenders in the world of research because – to adapt a quote first attributed to Charles De Gaulle - the country “needs finders not seekers”. Little wonder then, say critics, that public research in France is in an advanced state of decline.

“It's astonishing that Emmanuelle Charpentier, who won the Nobel Prize [in Chemistry] is in Berlin. That exactly illustrates the lack of resources that the state gives to research,” said Frédéric Genevier of OFG Recherche. There is indeed a lack of money throughout public research laboratories; to fund equipment, materials and even to pay salaries.

While a French research team might just about manage to get a budget of 150,000 euros over three years – 50,000 euros a year – for a project, a single American researcher alone can obtain 5 to 6 million dollars over 5 to 6 years for an equivalent project. Even where European budgets are of a decent size they still sometimes have to share the money between 15 or even 20 different teams.

As a result pharmaceutical firms in France, including Sanofi, have realised that there is no financial help coming the way of public research whatever its quality. “Ten or fifteen years ago cooperation between public research and Sanofi's research centres did exist, especially in Toulouse. But now the links are limited,” said Jean, the researcher at Inserm. Sanofi got the message as did all Big Pharma groups: and it looked to the United States where the money was.

Financial returns over innovation

It is a major characteristic of French capitalism and one of the results of the policy of picking national champions; French groups like regular, easy profits, whether that is from motorway tolls, in telecoms, building or energy. Once in a position of near monopoly – or oligopoly - all their main energy is devoted to maintaining that income flow, by increasing their lobbying of the public authorities.

Sanofi is no exception to this rule. Priority is given to creating or preserving financial returns rather than to innovation. Having inherited the heart of the old French pharmaceutical industry, the group has developed a tight network of contacts to help ensure decisions go in its favour, whether these are over the pricing of products or getting its medicines into the marketplace.

The lack of transparency caused by the proliferation of agencies and committees in the area of health and medicines (the Agence Nationale de Santé, Agence du Médicament, Santé Publique France, Haute Autorité de Santé, ANSES, ANSM and so on) assists this approach. For it makes it impossible to clarify what the company is asking for and what commitments it has made, or whether there are any conflicts of interest.

The dominance of finance in the pharmaceutical industry means that research is now treated as a cost centre. It is also seen as being too bureaucratic and in need of a shake-up. The first restructuring plans at Sanofi were announced by Christopher Viehbacher in 2009, with the closure of the centre at Toulouse. This caused a shock inside the group. “When you joined a Sanofi research centre it was for life,” explained Marion Lessac from Sud Chimie.

“Sanofi speaks about research. But we no longer do any initial research like we did before. Our research centres have become development centres. We work on drugs that others have found,” said Sandrine Caristan, the researcher at the Sanofi centre in Montpellier and representative of the Sud Chimie trade union. Some staff at the group have felt discouraged as a result.

A name cited several times in this context to Mediapart was that of Tal Zaks. A specialist in immunology and oncology, he worked in a senior role at Sanofi from 2010. He left the group in 2015 after apparently failing to find the support and ambition he needed at Sanofi. He became chief medical officer at Moderna, which has produced one of the vaccines approved for use against Covid-19.

Appeals were made to start working on messenger RNA

Caution seems to be the watchword throughout Sanofi. “We've known about RNA messenger [editor's note, a molecule that carries a portion of the DNA code to other parts of the cell for processing] for ten years. Several alerts were made internally calling for us to start working on that, for us to develop our drugs, our own expertise. Management didn't want to,” said Fabien Mallet, a CGT official who works at Sanofi. To develop its second vaccine, which does use messenger RNA, Sanofi instead preferred to link up with the American biotech firm Translate Bio.

Like all the other major players in the pharmaceutical industry, the group now thinks it is easier and less risky to buy start-ups, to take over patents and medicines, to outsource its research and to do trials using third parties rather than create new medicines in-house.

In effect, the group has become an appendage of merchant banks, making more and more acquisitions, sometimes paying a fortune in the process. Yet it does not feel duty bound to take part in the development of biotechnology firms or research in France.

An example of this phenomenon is the company YposKesi, which specialises in viral vector manufacturing, and which was funded at the start by the AFM-Téléthon televised public appeal in France and by the public investment bank BpiFrance. It got no help from Sanofi or the pharmaceutical sector in France in general to help it develop. It has just been bought by a South Korean company.

It is possible to argue that YposKesi's speciality is not part of Sanofi's area of competence. But the same cannot be said about the company Valneva, which specialises in vaccines. It received support from neither the French state nor Sanofi. Instead it was the British government which gave it aid totalling 15 million euros, and Britain has now signed a deal with the company to provide 100 million vaccine doses, produced in Scotland.

“The big companies might be watching out for new technology and waiting to select innovative young firms in order to partner with them. However, recent research has highlighted possible incentives for the big companies to acquire a start-up with the objective of stifling at birth an innovation that might threaten their position, which is where the term 'killer acquisition' comes from,” Margaret Kyle and Anne Perrot say in their report.

This strategy is used across the world of Big Pharma and Sanofi is no exception. There are several examples, in the areas of medical treatments for leukaemia and multiple sclerosis, where Sanofi has preferred to kill off a competing medicine that might have eclipsed theirs.

Permanent strategic instability

“There was Transforming 1, Transforming 2.0, Phoenix, Pluto … Since 2009 there's been a plan every two years to save two billion euros,” said Jean-Louis Perrin, the CGT official at Sanofi in Montpellier. Over the past decade staff numbers at the group in France have declined from 28,900 to 25,000 people, and the number of researchers has fallen from 6,900 to 4,100. That was before the latest round of cost-cutting was announced.

The CGT official at Montellier has in fact summed up the group's strategy in those few short words. The search for short-term profit leads to a permanent strategy of instability, because everything is seen through the prism of immediate profitability and calls for permanent adjustments.

To start with, the group decided to get rid of all products where the rights to manufacture them had fallen into the public domain, as they were no longer profitable. Profitability on these drugs was hit even harder by the fact that France's medicines regulator, the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament (ANSM), has put downward pressure on prices by encouraging the use of generic products, most of them coming from India.

Then the group decided to get rid of small-scale medicines from their portfolio, those typically available at a pharmacy and via prescriptions from a family doctor. Instead, Sanofi wants to devote itself to the development of more expensive medicines, in particular for use in cancer treatment, that are only used in hospitals. This led to getting rid of many of the group's drugs sales representatives.

Meanwhile, and in common with its rivals, Sanofi has chosen to move the production of its main active ingredients offshore. Europe thus discovered with alarm that there is no longer a factory on the continent able to manufacture paracetamol.

In 2015 the group gave up on its animal vaccines business and its company Merial, based at Lyon in eastern France, was sold to the German pharmaceutical firm Boehringer. Up to that point veterinary research had been one of the main areas for the study of coronaviruses.

After this came the move to get rid of the anti-infectives side of the business, antibiotics. Having restructured this side of the business three times, moving it from Romainville in the Paris region to Toulouse in the south west of the country and then Lyon, this activity, which in the past had been so important to the group, was simply handed to the German biotech company Evotec. Thanks to an agreement under which Sanofi paid 60 million euros, the German firm is committed to keeping the jobs of the 100 who work at Lyon for three years.

“Today the epidemic is linked to a virus. But tomorrow it could be a bacteria. And the situation would be even mores serious. Because we won't have the necessary antibiotics,” said Sandrine Caristan. “For years the World Health Organisation has been warning about the resistance developed to antibiotics and have called for the development of new antibiotics. Sanofi refused to do that. And now the group is getting rid of the lot.”

Another PR exercise?

Paul Hudson, who became CEO at Sanofi in 2019, has decided to pursue a new strategy in order to “shake up” the group. The group has announced plans to stop all new research in the areas of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The new boss also wants to move further towards biotechnology – by a process of acquisitions - and relinquish the production of basic ingredients for medicines. It is thus setting up a new company, provisionally called Euro API, with API standing for 'active pharmaceutical ingredients'. This company will include six existing production and research sites – at Brindisi (Italy), Frankfurt Chemistry (Germany), Haverhill (UK), St Aubin les Elbeuf (France), Újpest (Hungary) and Vertolaye (France) - that make these ingredients. This company will ultimately be sold, with Sanofi retaining up to 30% of the new business.

“We're in the process of destroying our know-how. Sure, the biotechs are coming but they can't replace everything. And we also need pharmaceutical production to make these new medicines,” said Jean-Louis Perrin. “If we had scientists worthy of the name on the board, they wouldn't accept what's currently going on.”

On several occasions groups of doctors and researchers and the independent group on transparency in medicines, the Observatoire de la Transparence dans les Politiques du Médicament, have tried to raise the alarm. They point out that public policy cannot be be dictated by decisions made in the private sector. All are worried about what they see as the extreme vulnerability of a French health system that is more and more dependent on being supplied from abroad.

These groups are calling for an examination of the current system to evaluate the country's needs and shortcomings. They want a genuine medicines policy that would see production brought back to France at a time when the health sector has taken on a strategic importance that is on a par with defence.

But it appears as if no one in government is dealing with the issue. No one that Mediapart spoke to was aware of any work or studies being carried out by the state to make a genuine assessment of the situation and the threats the health and medicines system faces. The finance and economy minister Bruno Le Maire may have insisted that pharmaceutical production returns to Europe in general and France in particular. But in reality nothing has changed and the state is refusing to intervene.

Under pressure after the recent setback over a Covid vaccine, Sanofi's CEO Paul Hudson promised in an interview with Le Figaro newspaper that they would work as a subcontractor and produce vaccines created by competitors. But no one understands why the group is undertaking to make such a small volume – 100 million doses – and so late – not before July – when its production plant in Frankfort is available. That was the production line that was supposed to be producing Sanofi's own delayed vaccine. He also committed the group to bringing pharmaceutical production back to France.

Staff see this as yet another PR exercise. “Not one square metre will be created. It's just about transferring the production plants into the new structure,” said trade union official Jean-Louis Perrin.

The French government appears to be happy to go along with it.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter