On December 11th 2020, French pharmaceutical group Sanofi and British pharma firm GSK (GlaxoSmithKline) announced that their joint development of a vaccine against Covid-19 was delayed after the first phase of clinical tests which began on September 3rd had shown “a low immune response” in the over-50 age group “likely due to an insufficient concentration of the antigen”.

In a joint statement, (here on the Sanofi website), the two said they now hoped the vaccine would be ready at some point in the last quarter of 2021 “pending successful completion of the development plan”.

The Sanofi-GSK adjuvanted recombinant protein-based vaccine – Sanofi is also due to soon begin clinical trials of another using the technology of messenger RNA – has now lost four months in a vaccine-rollout race between pharma firms that has already left it well down the ladder. In December, the RNA vaccine jointly developed by US drugs giant Pfizer and German biotechnology firm BioNTech was approved for use by a number of countries, beginning with the UK and US, and subsequently across European Union (EU) member states. That was followed by EU authorisation earlier this month for use of another RNA vaccine developed by US pharma company Moderna, which in December was already approved for use by Canada, the US and UK. Both vaccines claim an exceptional effectiveness of around 95%.

Meanwhile, a third vaccine, developed by Oxford University researchers and the British-Swedish pharma firm AstraZeneca is waiting in the wings for EU approval – expected by January 29th – after its authorisation by the UK and nine other countries.

Among the six different agreements signed between the European Commission and the vaccine manufacturers, that concerning Sanofi is the only one that does not include a firm pre-order for supplies (which in every case is conditional to obtaining marketing approval). The French industry ministry told Mediapart that the EU agreement with Sanofi for the supply of 300 million doses is "an option”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

For the EU to place a firm order for the Sanofi-GSK vaccine, the initial clinical trials must convincingly show the effectiveness and innocuousness of the vaccine, before it is subject to further trials on a larger scale. The option for 300 million doses was signed with the European Commission on September 18th, just two weeks after Sanofi-GSK began phase 1 trials. While Sanofi is one of the five largest vaccine manufacturers worldwide, there was no guarantee that its Covid-19 vaccine will succeed, and four months later the question remains.

But the French pharma giant and its British partner have already received financing from the European Commission for the development of their Covid-19 vaccine, paid out of the EU’s 2.7-billion-euro “Emergency Support Instrument” for fighting the pandemic. A large slice of that fund is for the securing of vaccines for member countries, including financing research and early production of vaccines even before they gain approval. If Sanofi decided to abandon development of its Covid-19 vaccine, it would have to repay the funding it has already been given.

“The Commission enters into Advanced Purchase Agreements with individual vaccine producers on behalf of Member States,” explains the European Commission on its website . “In return for the right to buy a specified number of vaccine doses in a given timeframe and at a given price, the Commission will finance a part of the upfront costs faced by vaccines producers from the Emergency Support Instrument. This funding will be considered as a down-payment on the vaccines that will actually be purchased by Member States.”

Sanofi told Mediapart that a total of more than 10,000 of its staff are engaged on the Covid-19 vaccine development programme, which represents about 10% of its workforce worldwide. Questioned by Mediapart, the Commission, Sanofi, and also the French industry ministry all declined to reveal how much EU funding Sanofi has received so far.

In May last year, Sanofi CEO Paul Hudson caused a storm of controversy when, in an interview with Bloomberg , he said the US would receive first deliveries of the company’s Covid-19 vaccine, then in the planning stage, because “it’s invested in taking the risk”. Bloomberg reported that “he warned that Europe risks falling behind”.

Hudson said the US, whose Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority had begun a partnership with Sanofi, was entitled to argue that “if we’ve helped you manufacture the doses at risk, we expect to get the doses first”.

“I’ve been campaigning in Europe to say the US will get vaccines first,” Hudson added, apparently upping the pressure for a deal with the EU. “That’s how it will be because they’ve invested to try and protect their population, to restart their economy.” Following those comments, France’s junior minister for industry, Agnès Pannier-Runacher, declared that “it would be unacceptable that there be privileged access for this or that country”.

Fabien Mallet, a CGT union official at Sanofi’s Neuville-sur-Saône production plant close to the south-east city of Lyon, where he works in the quality control department, also denounced the tactic. “To invoke the principle of first to pay, first served is absolute cynicism,” he said. “Sanofi wanted to remind Europe of its presence, in order to obtain pre-orders, even if it didn’t yet have the slightest start on a Covid-19 vaccine. It was just bluff.”

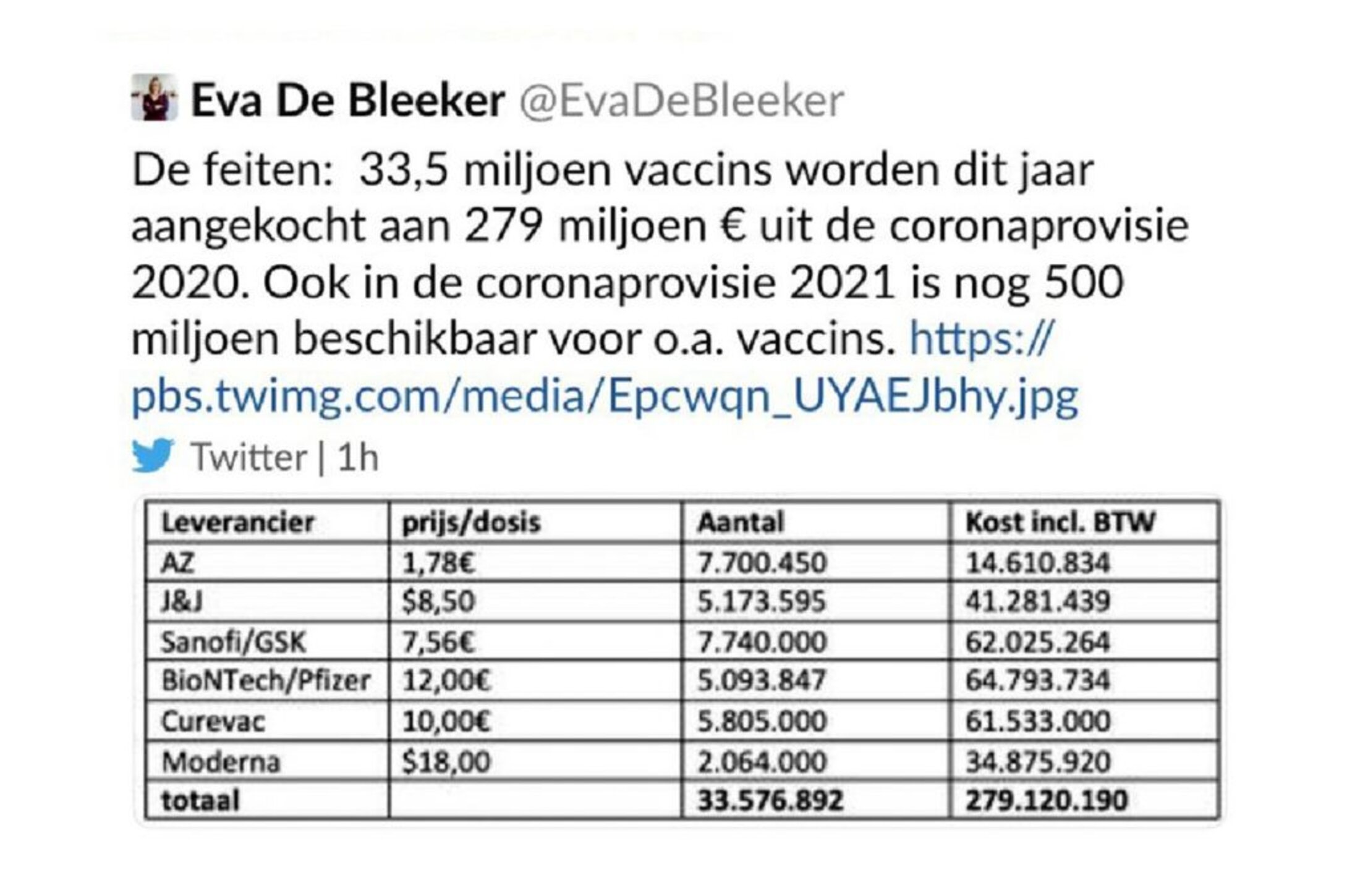

In December, the Belgian junior minister for the budget and consumer affairs, Eva de Bleeker, posted on her Twitter account the cost of individual doses of each of the six candidate vaccines proposed to the EU, as negotiated by the European Commission. The move was a political blunder because the information was supposed to remain confidential, and she swiftly removed the post. But screenshots that circulated afterwards showed that the Sanofi-GSK vaccine would, if approved, cost 7.56 euros per dose (the Oxford- AstraZeneca vaccine was cheapest at 1.78 euros per dose, while the most expensive was that of Moderna at 18 US dollars – or 14.8 euros). For Sanofi-GSK, that would bring in more than 2.2 billion euros for the hoped-for sale of 300 million doses

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“The securing of doses in the framework of the six initial contracts happened at a period when the clinical [trial] data for all the vaccines was still largely inaccessible,” the French industry ministry told Mediapart. The European Commission signed a pre-order for up to 300 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine on November 11th last year, when the joint venture had still not completely finished the last stage of its clinical trials.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was first approved by the UK on December 2nd, before the EU gave it the green light on December 21st. In a report published on December 18th on a potential shortfall of vaccine doses in Europe, German weekly Der Spiegel, asked why more doses of those vaccines promising high rates of efficacy, and notably that of Pfizer-BioNTech, had not been ordered by the Commission.

The weekly said German health minister Jens Spahn had suggested that the EU should purchase more of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. “He failed to prevail in the end,” reported Der Spiegel, “due to opposition from several EU member countries – in part, apparently, because the EU had ordered only 300 million doses from the French company Sanofi. ‘That’s why buying more from a German company wasn't on the cards,’ says one insider familiar with the negotiations. The European Commission has denied that version of events, saying it isn’t true that Paris took massive steps to protect Sanofi.”

Meanwhile, the Commission told Mediapart that it employed “objective criteria” to decide vaccine orders, and that the process “has nothing to do with the nationality of the manufacturers”.

Antoine Flahault is a French epidemiologist, professor of public health at Université Paris Descartes and the director of the Institute of Global Health at the University of Geneva. “Politicians defend their industry,” he argued. “It was fair enough for the French government to push for the Sanofi candidate vaccine, even if it had always been a bit behind. All the more so because it sometimes happens that a pharmaceutical company catches that up in the end if, for example, a serious undesirable effect occurs during a competitor’s clinical trials.”

At the end of December it emerged that Germany had finally signed its own unilateral deal with Pfizer-BioNTech for the purchase of 30 million doses of the vaccine, in parallel to the EU global order, over fears that its own share of that would not be sufficient. The move was criticised as weakening the principle of an EU-wide approach to purchases in order that all the continent’s countries, notably those less wealthy, would be treated in equal fashion. To defuse the row, the European Commission ordered an additional 300 million doses from Pfizer-BioNTech on January 8th, bringing the total deal to 600 million doses.

But Pfizer-BioNTech soon after announced that it would be unable to meet initial delivery schedules for Europe due to required modifications at its production plants in order to meet future demand, and notably at a manufacturing site in the Belgian town of Puurs. Deliveries of the vaccine are now expected to be disrupted over the coming three to four weeks.

Given the production problems encountered by Pfizer-BioNTech, and the delay in the development of Sanofi’s vaccine – which, at best, will not be ready until the last quarter of this year – some argue it would be in the public interest for Sanofi to use its dormant production lines to produce the vaccines of its competitors. The French industry ministry has reportedly urged Sanofi to consider the idea, and in an interview last week with French daily Le Parisien, professor Alain Fischer, an immunologist and president of France’s Vaccine Strategy Orientation Council, said he was in favour of such a move.

“We prefer to manufacture our vaccines rather than those of the competition but, given the context, it’s something to be studied because for the moment the production is at a halt,” commented Jean-Marc Burlet, an official with the CFE-CGC managerial staff union at Sanofi.

'Financial strategy takes precedence over innovation'

By the end of December, Sanofi had recruited around 100 out of the planned 113 staff to operate the production site for its future vaccine at Vitry-sur-Seine, close to Paris, along with around 50 others for its vaccine packaging plant at Marcy-l’Étoile, close to Lyon in south-east France. “Sanofi’s industrial sites were in line at the beginning of the year to begin producing its vaccine on a large scale,” said William Briant, a Sanofi maintenance technician and official with the CFDT union at the group’s production and distribution plant at Val-de-Reuil, in northern France.

“We would be ready to ensure the last stage of manufacturing of our competitors’ vaccines by becoming their subcontractor. The more doses that are available, whatever the name on the syringe, the quicker we’ll get out of this pandemic. Shouldn’t the management at Sanofi put their ego to one side at a period of a health crisis?”

Questioned by Mediapart, Sanofi sent the following statement: “Our priority is to put our science at the service of [battling] this pandemic. We can do this above all by developing our candidate vaccines. In parallel, given the unique circumstances of this crisis, we are studying supplementary possibilities for contributing to the fight against the pandemic and to help populations. That includes an evaluation of the technical feasibility […] to produce other vaccines. At this stage, it is still very preliminary, because the manufacturing technology is very specific to each vaccine. Once the feasibility evaluation is completed we will know whether this opportunity can be effectively put in place.”

On April 14th 2020, Sanofi CEO Paul Hudson sent an internal email to staff on the subject of the joint venture with GSK. “The cooperation between two large pharmaceutical firms is not common, and I am not sure whether, just two months ago, we would have envisaged a partnership of this type,” he wrote, translated here from the French version of the message. “But Covid-19 obliges us to place the status quo in question.”

Epidemiologist Antoine Flahault from Geneva university said if Sanofi was to reach an agreement with its competitors to produce their vaccines it “would be a good way to come away from all this holding one’s head high”, adding: “It would be a good thing that it participates in manufacturing weapons to kill the virus, even if these are not entirely ‘Made in France’. It requires four or five months to prepare such a chain for filling bottles.”

For Fabien Mallet, CGT union official at Sanofi’s Neuville-sur-Saône production plant, “The problem is that the state doesn’t dare put pressure of Sanofi to oblige it to do it”. Importantly, Sanofi receives around 100 million euros from the French public purse each year in the form of “crédit d’impôt recherche”, a system of tax breaks granted to firms that bis calculated on their spending in R&D.

But Mallet claimed a contributing factor to the delay in development of the Sanofi-GSK vaccine is the reduction in R&D personnel over the past ten years. Staff unions are currently mobilised against plans to shed what they believe will be a further 400 jobs in R&D through voluntary redundancies over the next three years. On Monday, Olivier Bogillot, the chief executive of Sanofi’s French operation, confirmed the group is axe posts in France and elsewhere in Europe. “There will be about 1,000 [employees] leaving in France over a timetable of three years, in different parts of the organisation including R&D,” he told news agency AFP.

According to Sanofi’s figures, it employs 10,000 staff in R&D around the world, of which 4,100 are based in France. That represents a fall in numbers since 2011 of, respectively, 9% and almost 23%.

Mallet argued that some R&D staff at Sanofi had left the group because it was outsourcing research into RNA vaccines, a technology used in those of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna against Covid-19, instead of developing them within the group. “This technology is the future, it is also an important avenue [of research] for treating cancers, but Sanofi chose not to back its development inside the company,” he said. Sanofi’s former director of its Global Oncology department, Tal Zaks, left the group to become Chief Medical Officer at Moderna, whose RNA vaccine was approved for distribution among EU countries on January 6th.

While the Sanofi-GSK vaccine is an adjuvanted recombinant protein-based jab, Sanofi is also developing a messenger RNA vaccine in partnership with US firm Translate Bio based in Massachusetts and specialised in mRNA-based therapeutics. Pfizer followed a similar course for development of its Covid-19 vaccine with BioNTech, based in the German city of Mainz, which is also specialised in mRNA, essentially for treating cancers. It was initially in that field that the two began cooperation in 2019.

Sanofi says that its vaccine developed with Translate Bio is due to soon begin the first phase of clinical trials, with a target of reaching approval at the end of 2021. The French group says the initial production of the vaccine will be managed by Translate Bio in Massachusetts.

Economist Nathalie Coutinet, a senior lecturer with the Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, who is specialised in the strategies of pharmaceutical firms and in European health policies, says that Sanofi’s choice to develop an adjuvanted recombinant protein-based vaccine with GSK was a conservative one and budgetary-minded. “Sanofi made the choice of developing within the company a technology that it knows well,” she said. “It is very nervous about biotechs. The financial strategy takes precedence to the detriment of innovation.”

Union official Fabien Mallet agrees: “Sanofi above all banked on technology that required the least investment in R&D. But it’s not because you have a vaccine against seasonal flu that the technique used is going to work on Covid-19.”

The phase 1/2 clinical trials of the Sanofi-GSK adjuvanted recombinant protein-based vaccine are due to begin again in February. If these do not lead to a convincing result for submission to the European Commission, no further EU funding will be provided, while if the project is then abandoned the two pharma partners will have to pay back the undisclosed funds already received.

Sanofi told Mediapart: “The specific terms of the complete agreement with the European Commission are currently confidential. However, we are open – upon agreement with the European Commission and our partner GSK – to divulge an expurgated version of the agreement to European Parliament members.”

German pharma company CureVac, one of the six vaccine manufacturers to have signed agreements with the European Commission, was the first to agree to show Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) an expurgated version of its contract with the EU. After months calling for the contracts to be revealed, French MEP Pascal Canfin, chair of the Parliament's health committee (and affiliated to the parliament’s liberal Renew Europe group), was finally able to consult the heavily redacted document on January 11th. The per-dose price of the vaccine, the number of doses to be delivered, information on the production sites and the amount received from the European Commission as a downpayment were all blacked-out, as was also two out of six paragraphs detailing the liability and indemnities regarding eventual side effects of the vaccine.

The conditions for consulting the document in a reading room were that this was limited to 45 minutes, that mobile phones were not allowed in, and that a confidentiality agreement must be signed.

Meanwhile, France’s industry ministry sounded a confident note on the prospects of the Sanofi-GSK vaccine. “There are more than 250 candidate vaccines currently in the course of development,” it said, and “the Sanofi vaccine developed with GSK still figures in the top 10 percent of vaccines likely to obtain marketing approval”. Unsurprisingly, Sanofi, via its spokesperson, insisted it was “very confident in the potential of [its] recombinant vaccine with the GSK adjuvant”, adding that the technology employed “allows to generate high and sustained immunity responses and potentially to prevent transmission of the virus”.

Whether the Covid-19 vaccines currently on the market can limit the circulation of the coronavirus is unknown, and the issue is of particular importance when the second phase of vaccinations, targeting the under-55s, is introduced – and which could include, if the final stage of clinical trials are successful, the Sanofi-GSK jab.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

This abridged English version, with some additional reporting, by Graham Tearse.