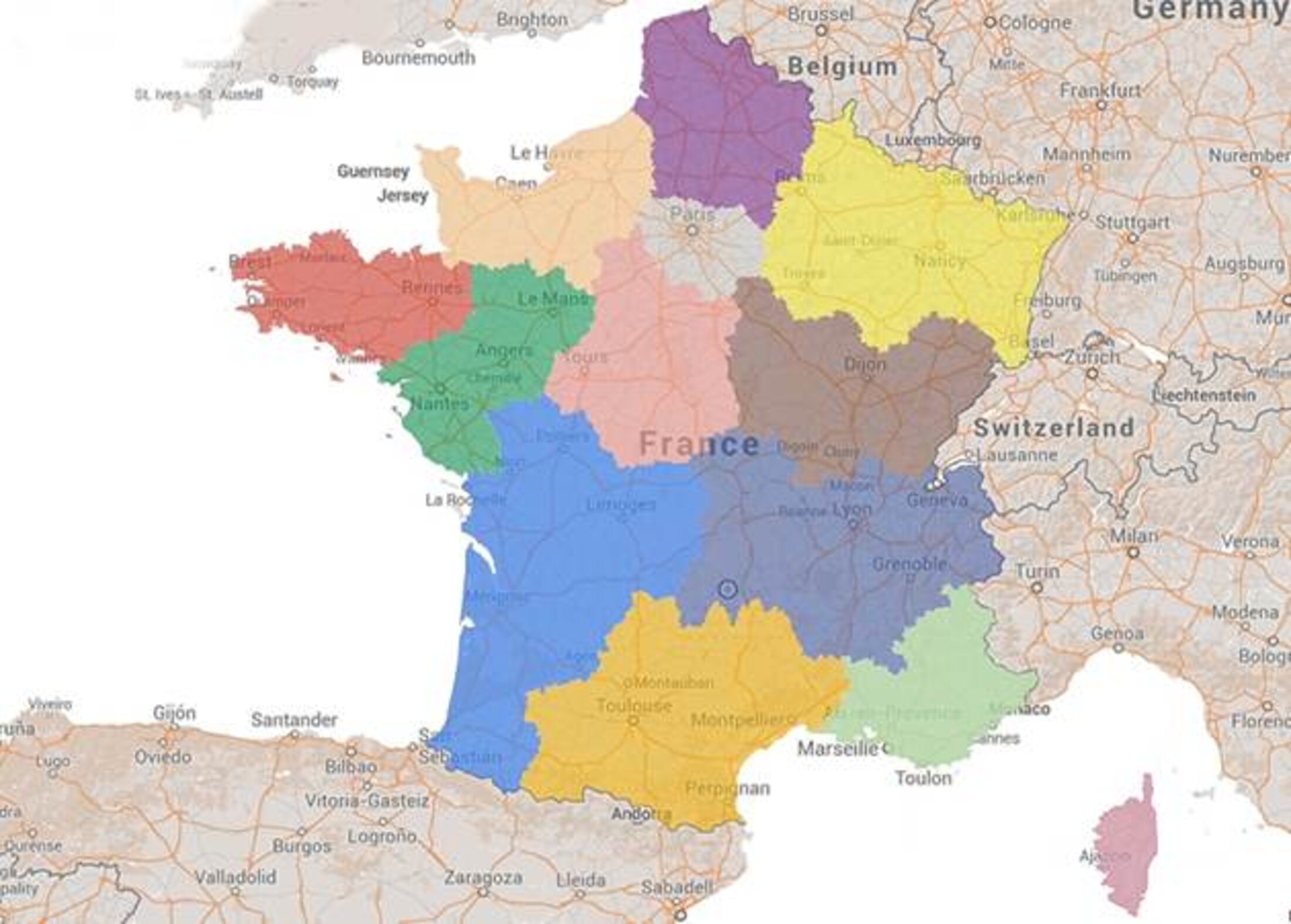

First there was the announcement of the boundaries of France's new super regions. Now the French government has revealed the names of the capital cities of those new regions. These were unveiled last week, on July 31st, as ministers met at their last cabinet meeting before the summer break.

The government reform, which reduces the number of regions from 22 to 13, creates seven new merged regions. The capital cities of these regions, which come into being from January 2016, are:

Strasbourg for the new Alsace, Champagne-Ardenne, Lorraine region in the north east;

Bordeaux for the new Aquitaine, Limousin, Poitou-Charentes region in the south west;

Lyon for the new Auvergne, Rhône-Alpes region in the centre east;

Dijon for the new Burgundy, Franche-Comté region in the east;

Toulouse for the new Languedoc-Roussillon, Midi-Pyrénées region in the south west;

Rouen for the new Normandy region in the north west;

Lille for the new Nord, Pas-de-Calais, Picardy region in the north.

Six regions remain the same and their capitals will still be:

Rennes in Brittany;

Marseille in Provence-Alpes, Côte-d'Azur (PACA);

Nantes in Pays de la Loire;

Orléans in the Centre;

Paris in Île-de-France;

Ajaccio on the island of Corsica.

The list of new capitals is, in theory, still provisional and will only become definitive in October 2016, well after the results of this December's regional elections. In some cases the choice of capital has been deeply contentious at local level, and has led to considerable debate and, in the end, compromises.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Earlier this year, for example, Brigitte Fouré, the centrist mayor of Amiens, capital of the current Picardy region, led a campaign for the city to be the “political capital” of the new Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Picardy region in the north, leaving Lille as its “economic” powerhouse. She and local right-wing MP Alain Gest launched a petition in February calling for local people to mobilise “so that Amiens can keep its historic place as regional capital and the many jobs that go with this status”.

When, instead, the government decided that Lille – whose mayor is former Socialist Party first secretary Martine Aubry – would be the new capital, Brigitte Fouré accused ministers of “downgrading” Amiens. This was despite a visit to Picardy by prime minister Manuel Valls on the eve of the announcement in which he tried to reassure the region. “Picardy will not disappear tomorrow because it is merging with Nord-Pas-de-Calais,” he said. “Its identity will remain...” The scale of the PR challenge facing the prime minister was highlighted by the local newspaper Le Courrier picard which greeted him with the headline: “Is Valls coming to bury Picardy?”

However, Valls has promised a compromise which will allow some important state regional bodies to have their headquarters in Amiens once the new region comes into force. This includes the headquarters of the local education service, plus the management teams for sports and youth, and for food, agriculture and forestry services.

There have been tensions in other regions, too, about the choice of capital. However, the tussle for this honour between Toulouse and Montpellier for the new Languedoc-Roussillon, Midi-Pyrénées region took place in a rather calmer atmosphere, after the respective mayors agreed earlier this year to work hand in hand. When Toulouse was formally chosen ahead of Montpellier the prefect – state official – overseeing the fusion of the two regions involved, Pascal Mailhos, said: “There is neither a winner or a loser.” Indeed, the headquarters of the eleven regional services have been split fairly evenly between the two cities, with six of them being based in Toulouse and the other five in Montpellier.

In the same way the north-west France town of Caen has been 'compensated' for losing out to Rouen as capital of Normandy by being able to play host to some key regional services. And similar arrangements have been made in the east of France where Besançon had to cede to Dijon as lead city in the new Burgundy, Franche-Comté region.

The choice of Lyon – France’s third most populous city after Paris and Marseille – as capital of the new Auvergne, Rhône-Alpes region was a logical one. But it also left the current capital of the Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, with a sparkling new regional headquarters that cost 80 million euros and which was inaugurated only last year. As part of the compromise over Lyon becoming capital, Clermont-Ferrand will apparently be able to keep its new building as the headquarters for several key regional services.

But while most of the choices of capitals were straightforward and, with the exception of Lille over Amiens, not too controversial locally, the way that the regional reform as a whole has been handled is still criticised, on the Left as well as on the Right. In the main vote by French MPs on December 17th, 2014, the reform was adopted by the relatively narrow margin of 277 votes to 253. Many MPs felt that a better approach to the reform would have been to decide beforehand what the new powers and role of the new regions would be, rather than start by drawing their frontiers. Critics say this could have avoided the spectacle of every local councillor in the country becoming a champion of their own little patch and arguing over different versions of the administrative map.

Though the fusion of smaller regions to create larger ones provoked debate in all areas, the most hotly contested moves were the merging of Languedoc-Roussillon with the Midi-Pyrénées, Nord-Pas-de-Calais with Picardy and Alsace with Champagne-Ardenne and Lorraine. After the vote last December around a hundred local councillors from Alsace staged a protest outside the National Assembly.

The junior minister in charge of the reform, André Vallini, says its objective includes making local government simpler and saving money; he estimates the changes will save 12 billion to 25 billion euros. However, this estimate is disputed by many critics and in any case the precise figures will be hard to verify. Another aim is to create larger and more powerful regions that will carry greater clout at European Union level. The minutes of the cabinet meeting last week noted: “Everyone wants from the different authorities more efficiency, greater unity, greater attentiveness to local needs, greater simplicity and more dialogue.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter