We had to wait three long weeks before Jean-Claude Juncker finally expressed his indignation. In the end the current president of the European Commission did grudgingly criticise his predecessor José Manuel Barroso for having become an advisor to the Wall Street bank Goldman Sachs. In an interview with Belgian daily Le Soir on July 30th, the Commission boss said: “I would not have joined Goldman Sachs. Incidentally, Goldman Sachs would never have asked me to. The fact that Barroso is working for a bank doesn't worry me too much. But for that one, that causes me a problem. It's an individual move and he respected the rules. But you have to choose your employer.”

A few days earlier Juncker had responded to a journalist from public broadcaster France 2 who asked him for his opinion on the affair. “I wouldn't have done it,” replied the former Luxembourg prime minister. It was not the strongest of condemnations. Indeed, up to now the Commission has kept on repeating that the decision by Barroso, who was president of the EU body from 2004 to 2014, was in their view perfectly legal. Rules already exist to control and, where necessary, block the revolving door syndrome – known as pantouflage in French – where top public servants walk out of their positions straight into lucrative private sector posts. But this code of conduct only covers the 18 months following the departure of the commissioner in question, known as the cooling off period. And when Barroso announced he had been recruited by Goldman Sachs he had already been out of his post for 20 months. In other words, it was technically speaking all above board. This is why Juncker told Le Soir his predecessor had “respected the rules.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The problem is, however, that Barroso's move has been catastrophic for the European Union's image. It reignites speculation that political decisions made in Brussels have somehow been “hijacked” by the world of finance. Many European officials in the Belgian capital are struggling to understand why Jean-Claude Juncker did not disassociate himself more clearly from his predecessor's toxic behaviour, particularly as from a political point of view Barroso no longer has any clout inside the Brussels 'bubble'. The German social democrat head of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, did not even judge it necessary to speak publicly about the subject throughout the whole of July. This was in contrast to the more decisive tone set by French president François Hollande, who on July 14th described Barroso's appointment as “morally unacceptable”.

“The Commission and Parliament are no doubt of the view that in these troubled times and media coverage, where one tragedy follows another, Nice coming after Brexit, it was enough just to let it pass,” Pierre Defraigne, the Belgian ex-chief of staff to former EU trade commissioner Pascal Lamy wrote with regret in a recent article. “But the Commission and Parliament are wrong, because they have a lot to lose in this episode: the former sees its moral authority weakened, while the second risks seeing voter turnout fall again at the next election. So why do they accept having a millstone around their neck that will burden them for a long time at great cost to the image of Europe in the eyes of its citizens?” He insists: “Europe is today too weak to add grave mistakes committed inside to the blows coming from outside.”

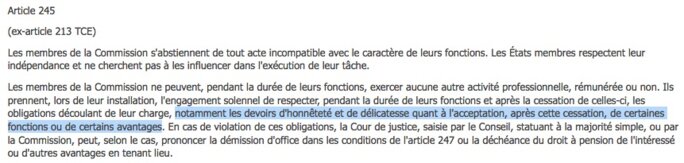

Pierre Defraigne's article reflects a growing debate in Brussels on possible ways to punish Barroso for joining the American bank. For many European officials it was the final straw. Staff from several European Union institutions, not just the Commission, have launched a petition that can be signed by any EU citizen. It attacks what it describes as a “further example of the irresponsible revolving-door practices, which are highly damaging to the EU institutions and, even if not illegal, morally reprehensible”. In the view of those behind the petition the argument that Barroso followed the process and respected the cooling off period is not good enough. They switch the debate to what European treaties have to say on such matters. In particular they quote a little known text, article 245 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which talks of the obligations of Commission members “both during and after their term of office”.

Article 245 notes the “duty to behave with integrity and discretion as regards the acceptance, after they have ceased to hold office, of certain appointments or benefits”, without defining those terms. So, by accepting a position at Goldman Sachs, has Barroso shown “lack of integrity” or “indiscretion”? The authors of the petition, who remain anonymous because as civil servants they are under a duty not to get involved publicly in controversies, are in no doubt that their former boss has. Once they have finished collecting signatures between now and the end of September, the employees will urge either the Commission or the European Council, which represents member states and is presided over by Donald Tusk, to refer the issue to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg to see if Barroso's appointment is consistent with the treaties. This could ultimately allow Barroso to be punished, for example by “the suspension of his pension allowance as former President of the European Commission for the period of his employment at Goldman Sachs and beyond”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Just like any other former European commissioner, José Manuel Barroso has the right to a pension from the age of 65. But he can ask to draw a partial early-retirement pension from the age of 60, which the Portuguese former official, born in 1956, has in fact done. Since April 2016 the EU has paid him a pension, indexed on his final salary, which corresponds to 70% of what he will be able to draw once he turns 65. According to Mediapart's calculations Barroso, who was in post for ten years, is currently getting a pension of just over 7,500 euros a month. But the Commission itself has refused to confirm or deny the figure. (See here for details on how Mediapart calculated the figure.)

Other groups within the Brussels bubble have also entered the fray in recent days, citing the same article 245. For example the Union for Unity (U4U), which represents EU staff, and which says it is “shocked” by a move that could “make the European construction even more unpopular and could discredit our institution”, is calling on Juncker and the college of Commissioners to make a “firm statement” and above all an “appropriate decision ... on the recruitment of the most prominent leaders of the EU in regard to the general interest of European citizens”.

In the European Parliament an 'intergroup' – an informal all-party gathering of Members of the European Parliament who meet on a particular subject – that deals with transparency in public life and the fight against organised crime has also sent a letter to Juncker. It urges him to “to launch a legal procedure based on article 245 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU”. This letter was signed by MEPs from seven of the eight political groups based at the Strasbourg-based parliament, including a member from the right-wing PPE group, the political family to which Barroso himself belongs, and which has been very quiet on the affair until now. More generally a number of MEPs have already expressed their anger over the Barroso affair, notably French socialists and Greens, with the majority calling for an extension of the cooling off period for senior officials joining private firms, in some cases to up to five years.

If Juncker seems reluctant to condemn Barroso's appointment at the Wall Street bank it is partly because he does not appear to have understood the deeper problem. In his interview with Le Soir, the Commission boss drew an unexpected distinction between going to work for “a bank” and going to work for “Goldman Sachs”. The Wall Street giant is not, of course, just any financial institution and played a controversial role in the sovereign debt crisis that shook Europe from 2008.

But what is at stake here goes well beyond one single American investment bank. It involves all cases of 'revolving doors', of senior figures heading off to the private sector, of which there are many examples in Brussels. Indeed they provoke regular rows and have a devastating effect on public opinion. Only Jean-Claude Juncker seems not to have yet understood this. In the summer of 2014 the British Liberal Democrat MEP Sharon Bowles, who up to then had been chair of the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, a key position during the financial crisis, moved to the City in London as non-executive director of The London Stock Exchange Group. In 2015 Holland's Neelie Kroes, who under Barroso had been commissioner for competition then for the digital agenda, became a special advisor on Europe for another major player on the United States financial scene, Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Then in May 2016 she was also appointed as an adviser to the controversial taxi-booking operator Uber.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter