In the Marne département (county) in north-east France, Jean-Baptiste Prévost, a farmer with around 280 hectares of field crops is uncertain of even breaking even this year amid a drought that has significantly reduced yields. This now recurrent phenomenon threatens an uncertain future.

The north and the north-east of the country are the regions worst-affected by the lack of rainfall since the beginning of the summer. The yield of the 60 hectares of barley crops grown by Prévost over the past 15 years has this year dropped to an average of 5.5 tonnes per hectare compared with an average 7.5 tonnes per hectare in the past. He sells the barley to the beer-brewing industry, and adding to his woes is the downturn for the latter caused by the Covid-19 virus epidemic and which has cause prices for the grain to plummet.

As for the farmer’s potato crop, Prévost envisages a fall of between 15-20 tonnes in his usual production of 50 tonnes per hectare. Planted in April this year, they have been stagnating since the beginning of the summer. “The tubers are not growing anymore, the branches are withering,” he said. “They’re dry when you tap them.” The only immediate solution he can find is to build little water-collecting bowls between the mounds of potatoes, but for that to be effective it must rain.

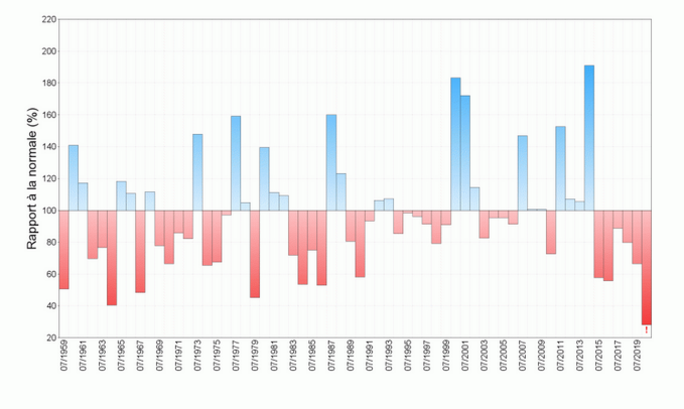

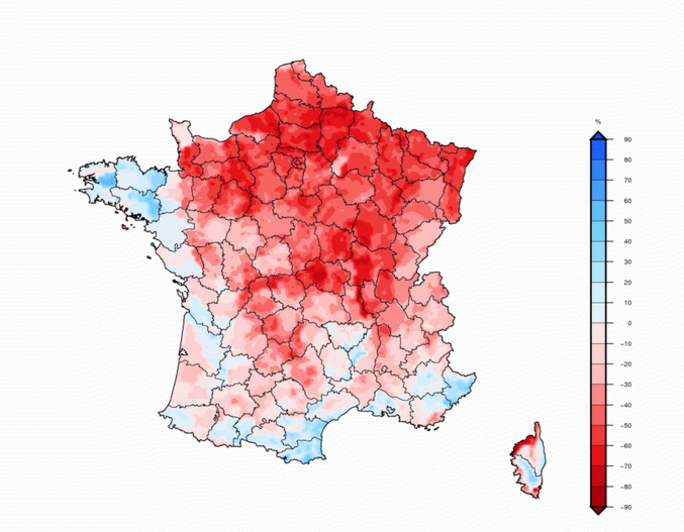

In July, France experienced its lowest rainfall since the national meteorological office, Météo France, began recording it on a national scale in 1959, and the phenomena of summer droughts has been significant since 2011.

Prévost is thinking about changing his choice of crops to adapt to the new climatic conditions, perhaps no longer planting potatoes or finding a variety that can survive the dryness, or planting peas. His concerns are shared by many farmers for whom the summer droughts are now threatening the economic survival of their businesses. The figures are alarming. At a national level, common wheat yields by July 27th this year were estimated by the agro-industry market evaluation firm Agritel at 29.2 million tonnes, down by 26% on the same period in 2019. It was the third-poorest harvest of the past 25 years.

In the Saône-et-Loire département in east-central France, cattle farmer Jean-Michel Rozier was used to being self-sufficient in feeding his around 100 heads which would graze on 150 hectares of pastures. But for the past three years, that has changed. The land produces ever less grass, and to get through the winter he has to buy in silage. That costs him between 15,000-20,000 euros more than before. “This year is the worst of all,” he said. “Just 180 millimetres of rain fell on our place since the beginning of the year. The prairies are yellow, burnt. They are degenerating. In places, you even see the earth. It is mentally very difficult.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

At the height of summer, Rozier now feeds his cattle with silage, whereas they would previously have been grazing in the fields. “Some stockbreeders have even brought their animals into the buildings, which we never did before,” he said. The result is that the animals’ health suffers. Rozier said that over the past three years he has seen their carcasses reduced by between 50-70 kilos per piece, while dairy cows are producing ever less milk.

Faced with the very probable continuation, and worsening, of the droughts, Rozier is planning to radically adapt his farming practices. “We’re going to lower the number of cattle,” he said. “We’re also going to stop growing maize for the dairy cows. In eight days’ time, we’re going to have to ensile it whereas it hasn’t been in the ear.”

Maize production, which demands plenty of water, represents one of the major changes required of French agriculture if it is to prove more resilient. Maize production accounts for more than half of irrigated crop farming in the country (which in total accounts for just 5% of farmed land), and 60% of it is destined to feed animals.

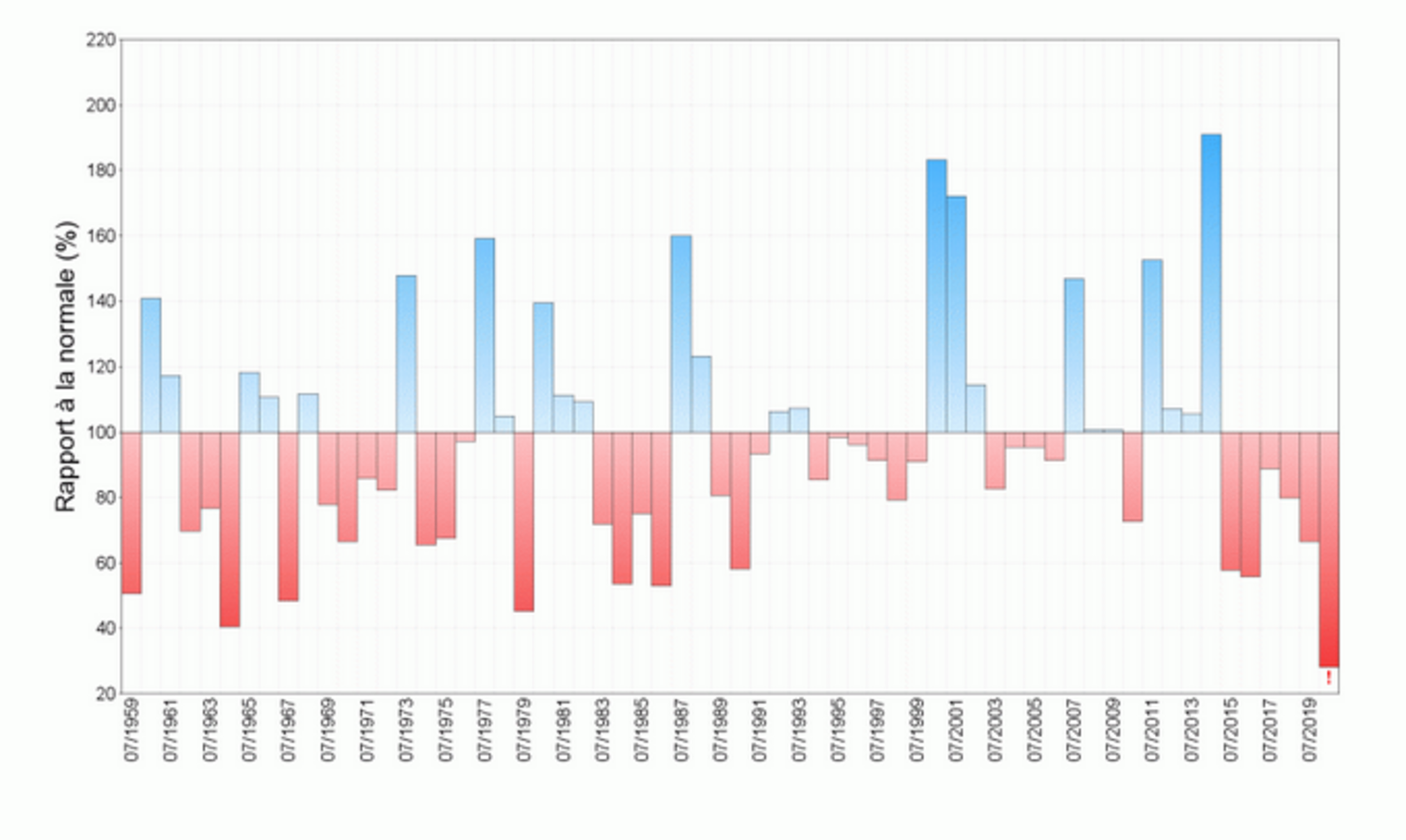

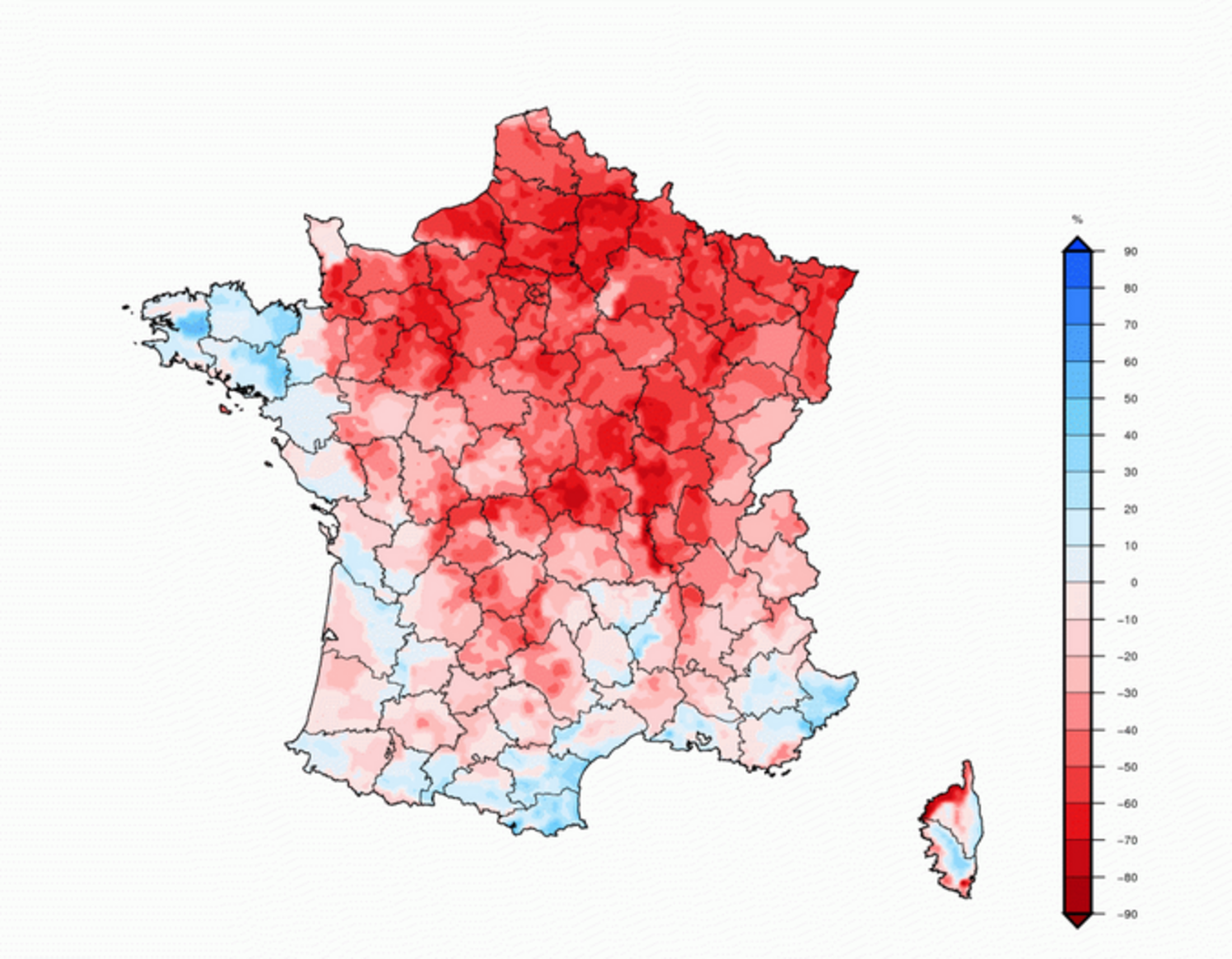

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“The question of the choice of crops and our food [supply] system must be asked,” said Pierre-Marie Aubert, an agricultural engineer and researcher with the independent Paris-based think tank, the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI). “If we reason with a constant [form of] food system, the options are limited. But if we decide to reduce our meat consumption, we would then have need of fewer animals, fewer cereals, and so less water.”

Meanwhile, there are cereals which are much more resistant to drought, such as sorghum (also called “great millet”, and which is currently grown on a very limited scale in France) than those traditionally grown.

‘There is no miracle solution’

The situation today is plainly alarming; 2020 is another record year of drought in France, in the lineage of those of 1976, 2003 and 2016. In face of the crisis, no less than 68 départements out of a total of 101 (including those overseas) have now introduced restrictions on the use of water.

According to Jean-Michel Soubeyroux, a climatologist with Météo-France, droughts are set to progress further in the years ahead. “The current drought is due to a deficit in rainfall, together with the heat that produces a more rapid evaporation,” he explained. “It is the soil which is affected. The rise in temperatures due to climate change will only aggravate the phenomenon.”

While the levels of the groundwater table are not a subject of concern this year, given the heavy rainfall during the last autumn and winter, the current drought once again highlights the issue of water management. Water, that increasingly rare resource, has to be shared between different usages – those of agriculture, industry, energy production and common public consumption – which find themselves in conflict with each other.

Amid this sharing, it is agricultural usage which takes up the lion’s share. Agriculture accounts for almost half the water used in France per year, and in the summer period its share rises to around 80%..

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“Measures must at all costs be taken to avoid us seeing a war over water,” said Loïc Prud’homme, a Member of Parliament (MP) for the radical-left France Insoumise party, who this year presided a parliamentary fact-finding commission into water management during periods of drought. “Things are always done too late,” he added. “It’s when the shortage is there that the question of how to remedy that is posed.”

Prud’homme said he was unimpressed by the announcement last week by France’s newly appointed agriculture minister, Julien Denormandie, that help would be provided to set up small-surface water reservoirs for the irrigation of fields, an idea championed by the largest of French farmers’ unions, the FNSEA. “To say that to farmers, is to say that they can continue with the same model, watering fields of maize in the afternoon when it’s 40°C,” commented Prud’homme.

Moreover, the improvisation of small reservoirs for irrigation, which are basins of collected water, produce a waste of water because of their exposure to heat and evaporation. “This type of measure will never allow for treating all the agricultural area which, for 95% of it, functions without irrigation,” underlined agronomist Pierre-Marie Aubert of IDDRI. “It’s a stopgap which will only serve to delay the moment when it will be necessary to radically change conventional agriculture.”

Pumping from the groundwater table’s finite reserves is not a solution either. “To increase irrigation is a dead-end,” said Sylvain Doublet, an agricultural engineer and member of Solagro, an EU-funded association that advises on sustainable farming methods and environmental and energy policies. “If everyone wants water, no-one will have any.”

For MP Loïc Prud’homme, “What’s needed is to help farmers to look again at their choice of crops, and to slow down the water cycle”. By this, he is referring to employing means to keep water below the surface of the soil through natural methods, by restoring vegetation to prevent water streaming off the land, increasing amounts of organic matter in the ground, and replacing surfaces in urban areas which do not allow water to sink into the soil.

“Behind the issue of water management is the management of the soil,” said IDDRI’s Pierre-Marie Aubert. For him, maintaining a soil rich in organic matter increases its capacity to stock water, while also rendering it more capable of capturing carbon, with obvious benefits in helping to counter climate change. To succeed with this, there must be a reduction in the use of chemicals that infiltrate the land, and also of the use of tractors, along with the introduction of a longer cycle in crop rotation.

To encourage small farmers in economic difficulty to address the problem by adopting environmentally positive methods, the parliamentary commission presided by Prud’homme advised, in its report of conclusions published in June, the creation of a 1 million-euro fund which would award payments for “environmental services”.

Some experts argue for a change in sowing and planting practices to allow crops to be grown outside of the periods of greatest drought. An example here is winter beetroot, which is sown in the autumn and harvested in spring, as opposed to currently grown types of beetroot whose much shorter cycle is between July and August.

Another practice that is already gaining ground among smallholders – although less practical for large farms – is the planting of hedges around fields to cutdown drying winds, and also positioning trees to provide shaded areas.

“There is no miracle solution,” warned Sylvain Doublet of Solagro. “To make the agricultural system resilient to drought, a combination of solutions must be put in place. There must above all be a diversification of crops in order to not place all one’s eggs in the same basket, and to develop plants that are more resistant to water stress.”

Jean-Claude Bevillard, specialised in agricultural affairs for the federation France Nature Environnement, an umbrella organisation for several thousand environmental associations across France, also insisted on the need for a diversification of crops and also the sales outlets farmers use, although he said such a change is difficult to envisage given the current system is “dominated by the cooperatives” through which produce is sold.

In this context, organic farming, as opposed to conventional, high-yield agriculture, appears better armed against the problem, with smaller production requirements and methods which include an implicit respect for the environment.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse