“Rather than a deep reflection on the basis of a renewed social contract which was less prescriptive and more pragmatic, ideology took hold. 'Je suis Charlie' became the magic label that you bandied around for your own interests, struggles and prejudices; in plain terms, an order. This order, which inevitably harmed the initial momentum, varied according to who used the slogan. It sought to bring together as much as to exclude, to bring together by excluding...”

These comments are not from an “Islamo-Leftist”or a dangerous sociologist looking to excuse rather to explain, but from an article by Philippe Lançon, a journalist at Charlie Hebdo and Libération, who was seriously injured during the massacre carried out by the Kouachi brothers Saïd and Chérif which killed many staff on the satirical magazine three years ago.

It was one of these scaled-down invocations of “I am Charlie” that was in evidence at a special meeting in central Paris on Saturday January 6th to commemorate the events of three years ago. Entitled 'Toujours Charlie! De la mémoire au combat' ('Still Charlie! From Remembrance to the Struggle'), it was organised at the Folies Bergères nightclub venue in Paris by three groups; the pro-secular Printemps Républicain, the secular campaign group Comité Laïcité République and the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism or LICRA.

As the historian, author and philosopher Élisabeth Badinter summed it up, in the most-applauded comments of the meeting, “the acts of intimidation carried out by Islamists and of shaming by Leftists have left their mark. Support at the beginning has been followed by 'yes, but': an elegant and hypocritical way of saying that they're no longer Charlie. To the question 'can one still be Charlie?' I therefore reply yes. But most of all, one must be Charlie.”

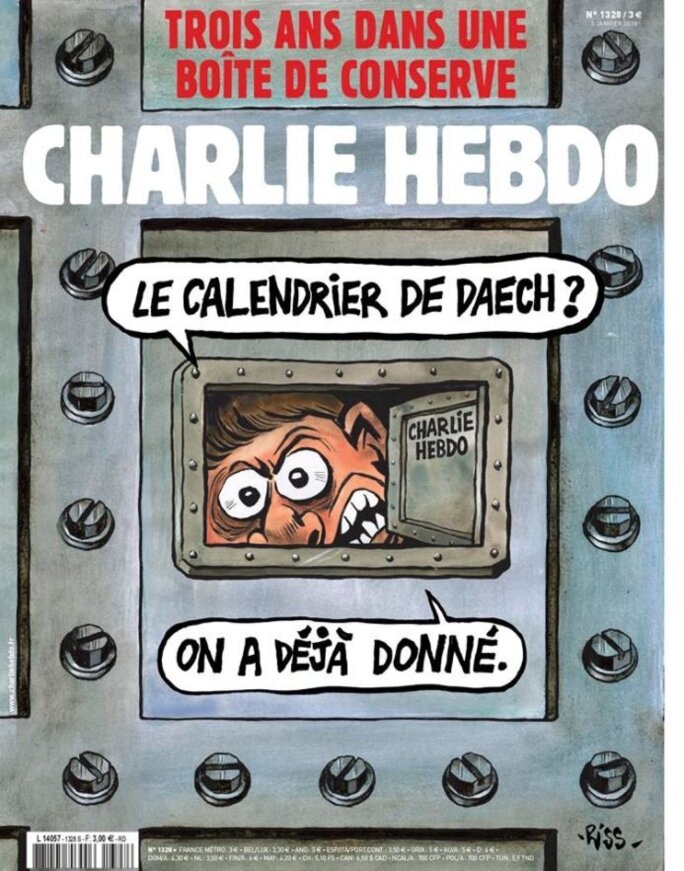

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The phrase “I am Charlie” was thus repeated like a mantra by all participants in the afternoon event but its meaning was never defined. Does 'being Charlie' mean remembering the victims and their loss in the jihadist attacks that hit France in 2015? Yes of course. But can we then claim the “right to bear testament to our grief and pain in the way that seems right to us” as was demanded by a group of professionals and local residents from the département or county of Seine-Saint-Denis just north of Paris? They took exception to one of the debates at Saturday's meeting, which asked whether it was possible to be “Still Charlie in Seine-Saint-Denis”, the département with the highest proportion of immigrants of France, many of North African origin and Muslim. In their open letter these Seine-Saint-Denis residents accused organisers of carrying out a “hunt” for “non-Charlies”, something they felt was underscored by the presence of journalist Nathalie Saint-Cricq, who once demanded that people who are “not Charlie” be “located and dealt with”.

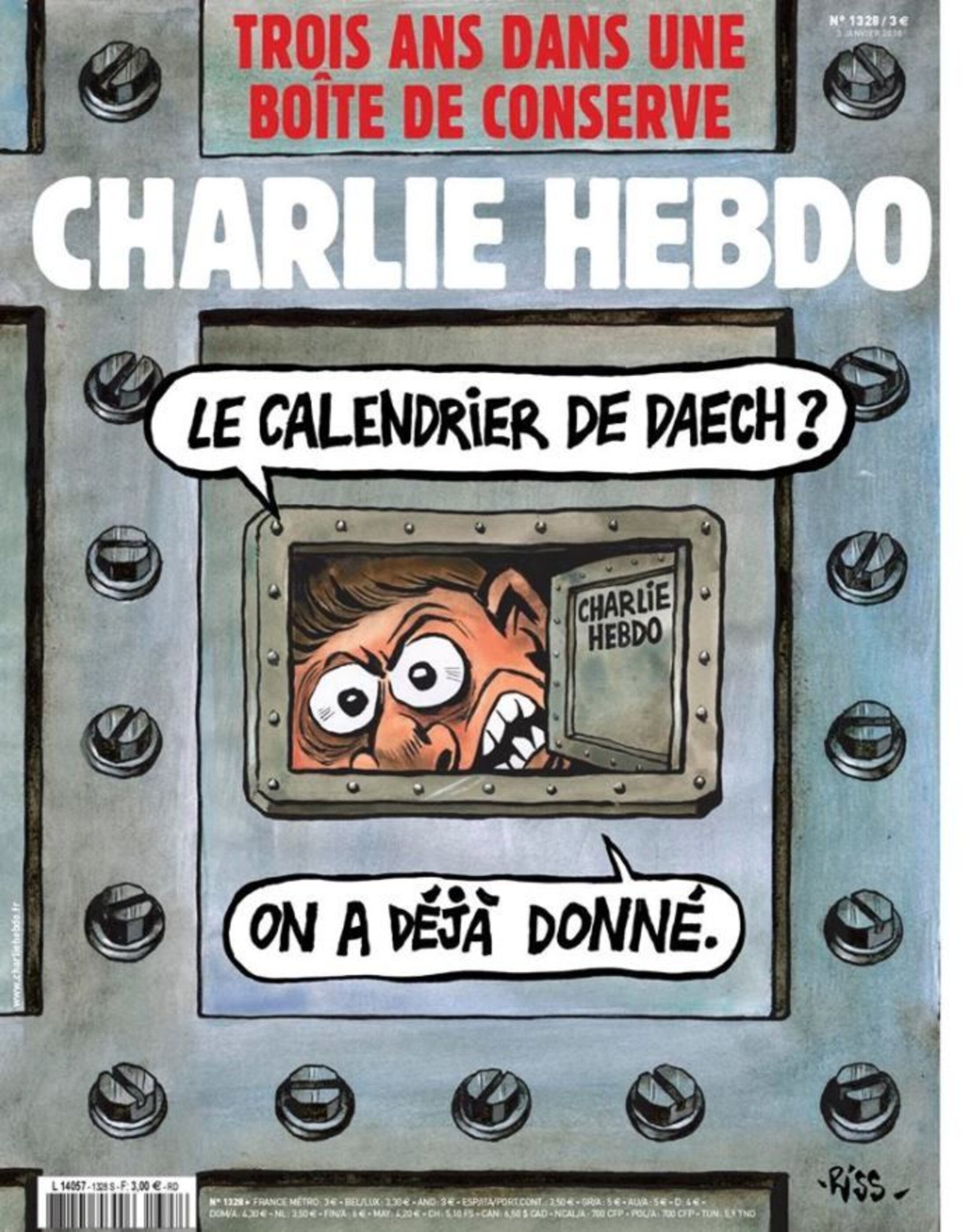

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Does 'being Charlie' mean showing your solidarity with a publication when it is threatened after its front page on academic Tariq Ramadan, even its cover on the late rock star Johnny Hallyday? Of course, but does 'being Charlie' mean, as the editor of Charlie Hebdo Gérard Biard says, refraining from “holding forth on good taste and the limits of humour”, even if it is indeed quite abnormal that “in a democracy, a newspaper of opinion should be forced to live under protection and that an editorial team meets behind reinforced doors”?

To put it another way, 'being Charlie' is of course to defend the freedom of expression. But is it also to make use of this freedom to criticise some of its positioning or those people who make use of the symbolic importance which the magazine enjoys to further their own political agenda? And does this freedom of expression also extend to the humorist Yassine Bellatar, the subject of an unfavourable profile by the magazine Marianne? This depicted him as the new Dieudonné – the controversial comedian – and an anti-Semite on the basis that his support for 'Charlie' was not unconditional.

Does 'being Charlie' mean defending secularism? Of course, but are we then talking about the neutrality of the state in religious matters as is defined in the 1905 law on the issue, or of the use that could made of this secularism to stigmatise France's Muslim citizens?

Does 'being Charlie' mean approving the satirical publication's entire editorial line, even if the philosopher and broadcaster on Europe 1 radio Raphaël Enthoven won the audience's approval on Saturday with his undeniable explanation that “what counts is not what is represented in Charlie but what Charlie represents” and that one had to make a distinction between “defence and support” because “when one says 'I am Charlie' it's not saying 'I subscribe to Charlie' or 'I agree with all of Charlie Hebdo's drawings'”?

The only, incomplete, attempt to respond to these important questions on Saturday came from the director of pollsters IFOP, Frédéric Dabi, who gave details of a poll they had carried out. On a sample of one thousand people, it showed that “three years after the massacre, the French are still and remain Charlie, but that this sentiment has eroded a little, in relation to a poll in January 2016”.

The pollster thought that the question of 'feeling Charlie' or not revealed “two Frances who are facing each other: a France which is doing well, which voted yes in the 2005 referendum [editor's note, on whether to accept a European constitution, though a majority voted no] who live in cities, who feel they are Charlie, and a younger France, coming from working class areas, based more in urban fringes and rural areas, who feel less Charlie”. He was worried that among those who say they are 'not Charlie', close to 39% were not content merely with the easy response that the attack took place three years ago and time has moved on, but instead they actively criticise the satirical publication's editorial line.

The monochrome panel of participants and the absence of contradictory voices did not really allow for a proper response to these questions, which were drowned out by demands, the closed-ranks nature of the gathering, and the way that the spirit of Charlie was employed to divide two political and media camps. As one left the hall one was tempted to ask the simplistic question: “Where is Charlie today?”

'Laugh at yourself so you can argue against yourself'

It was members of that first France defined by pollster Frédéric Dabi who filled the hall at the Folies Bergères on Saturday January 6th, much to the delight of Gilles Clavreul, a senior civil servant, who worked at the inter-ministerial government body fighting racism, sexism, anti-Semitism and discrimination against the LGBT community DILCRAH, and a founder member of Printemps Républicain. For him the large turnout to hear speakers such as former prime minister Manuel Valls, the conservative president of the Paris region Valérie Pécresse and the socialist mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo was a response to those who thought that the Printemps Républicain movement, created in the spring of 2016, “would not make it through the winter”.

It was indeed the approach of Printemps Républicain that dominated the gathering on Saturday at which, even though the victims of the attacks were cited and paid tribute to, the “memorial” aspect played second fiddle to the need for a cultural “combat” that was boiled down to one simple aspect: the defence of secularism. As Élisabeth Badinter, said: “While the 1905 law [editor's note, on the separation of church and state] was one of the great struggles of the 20th century, a section of the Left has become an accomplice to those most actively seeking to destroy this very secularism. They're seeking to destroy it by a game of adjectives, it has to be open, positive, appeasing. It's down to who can find the nicest adjective to differentiate them from others, but secularism has no need at all of a supervising adjective.”

In line with Printemps Républicain's agenda and obsessions the issues of veils, Islam, schools, public services and the Republic's lost territories were discussed at the gathering. This included lots of veiled messages and quite a few delusions too. For example, Élisabeth Badinter, who is one of the most powerful women in France, concluded her comments in this way: “I want to thank those major press titles who help our struggle, the first is the weekly Marianne, and the second the daily Le Figaro – I don't know if Charlie is really its cup of tea but it has opened its columns up to advocates of secularism to a large extent. Without these two newspapers we'd often be denied a voice.”

While we must listen to the concern raised on Saturday, and one which we can all share, about the weakening of Republican values and the jihadist threat, it is legitimate, too, to raise doubts as to whether what Raphaël Enthoven called the fight against “the scam of Islamophobia” and the exclusive focus on the quirks of Islam is an adequate response to terrorism. It is equally improbable that secularism can be the sole basis of the Republic without also a requirement for equality, a word which was missing from discussions on Saturday. Indeed, social and economic issues were almost entirely absent from the discussions.

'Being Charlie' may, to use the words of Rabbi Delphine Horvilleur - who at times seemed a slightly isolated figure during the meeting - mean knowing how to “laugh at yourself so you can argue against yourself”. Or, to pick up on Raphaël Enthoven's paradoxical comment, 'being Charlie' may mean “fighting for shades of difference”. But if so, it means rejecting a retreat into camps, the false symmetries and the political confusion which this meeting eventually unfortunately led to.

These outcomes can be summed up by the comments of journalist Bruno Couturier, who thought there was a “cultural war between the secular and Republican camp and the Islamo-Leftist camp, which is extremely powerful and infiltrating everywhere”. Or the remarks of another journalist present, Alexis Lacroix, who thought that there was a “cultural battle to wage. There's a twin pincer movement which is squeezing Republican universalism. We must resist the Plenelisation of the mind as much as the Buissonisation of the mind”, a reference to Mediapart publishing editor Edwy Plenel (see article on this here) and to Patrick Buisson the hard-right former advisor to President Nicolas Sarkozy.

Aside from the fact that you won't protect Republican values by caricaturing anyone who rejects the recurrent stigmatisation of Muslims in France as an accomplice to Islamists, can you really prevent the Buisson effect by inviting speakers such as writer Pascal Bruckner, whose comments are in line with the arguments espoused by the conservative news magazine Valeurs Actuelles? Bruckner has only just cancelled his involvement at a conference in Budapest - organised by the Hungarian government on the future of Europe - alongside the British polemicist and star of the American alt-right scene, Milo Yiannopoulos.

The spirit of January 11th will definitely not be saved by a few sorcerers' apprentices seeking to establish an improbable political space situated somewhere far to the right of what remains of French socialism.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter