“It was wretched, that’s how it should be said,” recalled Azzedine Naouri, talking about his childhood in a notorious shantytown populated by mostly Algerian immigrants, situated in the western Paris suburb of Nanterre.

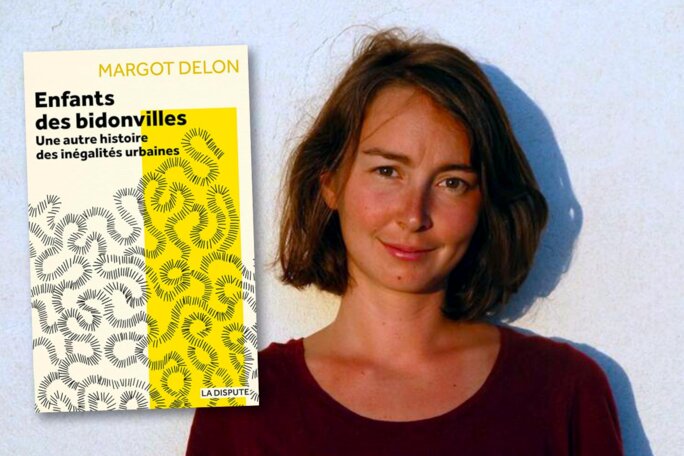

He was speaking to French sociologist Margot Delon, from the university of Nantes, who has conducted a study of the recollections and life paths of about 50 people, including Naouri, who grew up in two different shantytowns close to the French capital. Delon set out to establish “to what degree habitat determines each person’s opportunities” in life, and the results of that study were published earlier this year in France in her book entitled Enfants des bidonvilles. Une autre histoire des inégalités urbaines (Children of the shantytowns: another story of urban inequalities). Beyond the compelling stories of what became of those children, it notably offers an insight into the grim reality of a world from which thousands sought escape.

The insalubrious shantytowns, populated by many thousands of people, became established in France as of the 1950s, when the post-war expansion of the country’s economy, notably in the motor industry and building sector, attracted foreign labour, mostly from France’s former colonies in North Africa.

It is estimated that by 1966 in France, close to 75,000 people, made up essentially of Algerians, Moroccans, Tunisians and Portuguese, were living in the appalling conditions of the shantytowns, which continued to exist across such large sites up until the mid-1970s.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The sociologist focussed on the former shantytown cluster in Nanterre, which was home in the mid-1960s to a population of around 15,000 North African immigrants, mostly Algerian, and that of Champigny-sur-Marne, a suburb east of the capital, which in all housed a similarly-sized population of Portuguese families.

Among those Delon interviewed, some minimised the abject conditions they were raised in, while others fully relived the memory, with emotion. But there were common themes to all: for those from Nanterre, these included the environment of mud and the spread of scabies, both omnipresent, and the scuttling of rats, running noisily across the roofings of corrugated iron, and scaring the children. There was also the cold and the rain that invaded the family huts. One of the interviewees, Zohra Guerfi, remembered how her parents would take turns overnight to watch over the oil-burning stove through fear of a fire or intoxication.

The majority of families in the shantytowns included a parent in employment, usually the father, in which case the mother had charge of domestic chores. Beyond the physical hardships, there was also the stigma of being a slum kid. Mario Costinho, who grew up in the shantytown in Champigny-sur-Marne, said he remained haunted by the memory of how the Portuguese from his community were seated separately in the bus from the native French passengers. Karim Labed, from Nanterre, recounted the shame he felt about saying where his home was, and how the grubby conditions prevented him from inviting a schoolmate there. Rodrigo Mulhoz, from Champigny-sur-Marne, where conditions were not quite as dire as in Nanterre, told Delon: “I don’t like to talk about it because it was shameful to live like that. Even today, I don’t say that I had lived there.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The interviewees also spoke of the hostility and mocking insults they suffered as children from the camps, whether that be from the inhabitants bordering the shantytowns or even schoolteachers. One, from the mostly Algerian camp in Nanterre, remembered a teacher saying, “If you’re not happy, you’ll return to your own place to pick up camel droppings in the desert”.

Another interviewee, A French national of Algerian origin, told Delon that he was racially abused at school and had the impression that “somehow a part of my youth was stolen”. The sociologist underlined the broad process of exclusion he suffered, being regularly stopped in the street by police “under the approving eye of mistrusting neighbours, in face of institutions which refused to re-house his parents or to register him with the municipal sports clubs”.

Delon’s research also draws on documents from the archives of ministries, prefectures, social services and municipal administrations. Among the revelations from these is a document from a local housing authority which justifies its decision to limit the numbers of families of Algerian origin it can re-house because “their presence could have been badly received by the other inhabitants”. The re-housing that was offered, Delon writes, was limited to “the least attractive zones of the social [housing] stock”.

The sociologist outlines the different manner with which the immigrant workforces were regarded; the Portuguese were generally looked upon as being hardworking and competent, while the North Africans much the opposite. Delon states that the treatment meted out to the population of the cluster of shantytowns in Champigny-sur-Marne was less unfavourable than that towards those in Nanterre because the Portuguese were “a group attached to a European whiteness” whereas the North Africans were from “undesirable colonial” stock.

Delon suggests that Portuguese immigrants in France were akin to what US sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva describes as “honorary whites”, in this case meaning honorary members of the generations-old French population. She argues that the Portuguese “have been much subjected to what [the late Algerian-French sociologist] Abdelmalek Sayad called a ‘requirement of discretion’”.

“To guard against the ‘suspicion’ that weighs upon them,” Delon writes, “immigrants are compelled to give proof of ‘goodwill’, for example by not talking about their difficulties or violence suffered.”

She observes that it is schooling which rendered social ascension possible, as is often the case. Some of the children in Nanterre were helped in this by the fact that their parents spoke fluent French, but there were also the volunteers from poverty-fighting charities such as ATD Fourth World, and students from the nearby university of Nanterre, who offered assistance with the education of the children.

Saïd Mebarkia grew up in the shantytown in Nanterre, and has given Delon lengthy accounts of the abject conditions and prejudice he and others suffered from there. Now in his fifties, he is an example of those who, through education, escaped his situation and climbed the social ladder. But he is angry when he sees today, on his train journey to the northern Paris suburb of Saint-Denis, similar makeshift camps where people live in what he denounces as “impossible, intolerable, inhumane conditions”.

Meanwhile, for the youngsters in Champigny-sur-Marne, there was less available support from associations, and there was also less parental pressure on them to obtain high qualifications. Francis Neto, who grew up there, said that, in general, the Portuguese parents wanted their children “to know how to speak French well, that we knew how to read, write and that we had a good job – [but] they didn’t want us to be a doctor or a lawyer”.

Among the former children of the shantytowns, observes Delon, there are those who today display a strong empathy for those in precarious social conditions. She writes that throughout her research, “I was struck by the position of some of the interviewees who sought to fight against contemporary inequalities, to the opposite of ‘the last to arrive closes the door’ image of an immigrant, meaning they who themselves reproduce the structural ambient racism in order ‘to give proof’ and thus protect themselves”.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

- Enfants des bidonvilles. Une autre histoire des inégalités urbaines by Margot Delon is published in France by La Dispute, priced 14 euros.

English version by Graham Tearse