There are limits to political hand-waving. And when it comes to the nuclear industry, the new French government is in the process of overstepping those limits. Over the last week the government has behaved as if it were just discovering the issues confronting France's controversial nuclear sector and the industrial and financial problems that flow from them. Yet the new administration has known about the problems for a long time, and for a very good reason: the man who handled the dossier under the last government is now the president – Emmanuel Macron.

Though the new president tries to dodge responsibility for the previous administration's stewardship in general, on this particular question of the nuclear industry he cannot get off the hook. As minister for the economy from August 2014 to September 2016, Emanuel Macron steered the nuclear sector's decisions from beginning to end, imposing his views at every stage. It was he who chose Jean-Bernard Lévy to be president of the French utility giant behind the project, EDF, and he who oversaw the arrangements to hide the financial disaster of the nuclear sector.

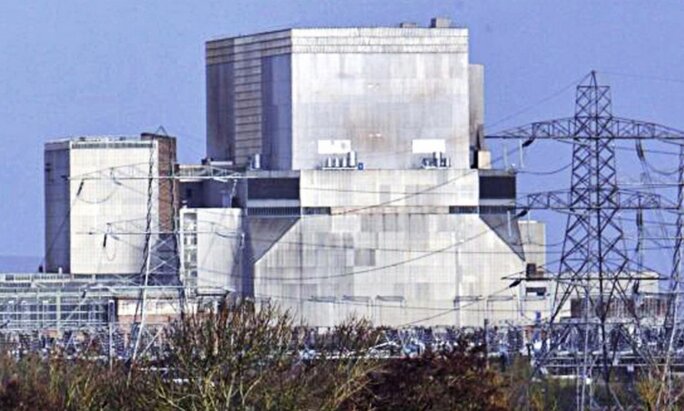

It was Macron, too, who used all his influence, including with a very reluctant President François Hollande, to make sure the Hinkley Point project went ahead, despite strong warnings from the EDF group's own engineers and staff. The construction of the two EPR third generation pressurized water reactors in south-west England marks the climax of an adventurism which could become a fatal trap for EDF and the public finances.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

So the new minister for finance and the economy, Bruno Le Maire, displayed a certain audacity when he used the report issued by the audit body the Cour des Comptes on June 29th on the state of public finances to talk of the “dishonest accounts” of the previous administration and its uncontrolled excesses. For among the budgetary problems under fire in the report were those of French nuclear firm Areva. The 4.5 billion euro increase in its capital, entirely underwritten by the state, risks leading to a “budget deficit of 2.3 billion euros or 0.1 point of GDP”, the Cour des Comptes said.

This arrangement, which was designed to hide Areva's bankruptcy, was set up while Macron was economy minister. It was his private office that came up with the idea to sell Areva's reactor construction business Areva NP to EDF to reduce the state's rescue bill, and then the nuclear group's recapitalisation. So well-known was this plan that it was approved by Areva's board at the end of 2016. But the operation was subject to agreement by Brussels, which made its approval conditional on the French nuclear safety body, the ASN, backing the new reactor at the Flamanville nuclear power station in north-west France. This was done on June 29th. The rest of the plan will now be put into operation. So how can ministers claim to be finding out only now about state commitments that have been known about for a long time?

The attempts by the current government to blame the previous administration for the state of pubic finances is one thing, though it smacks of the old style of politics that the new team had promised to break with. But the comments of Bruno Le Maire on July 3rd, after he had heard about EDF's announcement on the initial delays and budget overrun in the Hinkley Point deal, leave one speechless.

“The minister of the economy and finances has asked the CEO and chairman of EDF, Jean-Bernard Lévy, for the precise causes of this re-evaluation, the risk factor of the HPC [Hinkley Point] project and the content of the review of the project to be shared and analysed by the board of directors. The minister has also asked for a rigorous plan of action to be presented to the EDF board of directors before the end of July,” Le Maire said in a statement. The group had just confirmed that the cost of building the two EPR reactors in Britain risked going up by 1.8 billion euros and that the first reactor's entry into service could be delayed from 2025 to 2027.

So had the government, including all its spokespeople, only just discovered that the Hinkley Point project could become a risky venture? It's hard to imagine so. For more than 18 months many people, pointing to the setbacks at the EPR being built at Flamanville in northern France, have continually raised the alarm over the British project. A reactor that has still never worked and which we still don't know can be managed on an industrial level, a completely “unrealistic” timetable – even when the EDF was accustomed to building a series of reactors it never managed to complete a construction in five years as they have committed to doing at Hinkley – financial conditions which are not guaranteed and which directly put at risk the group's capital … critics fear that all the ingredients are there for the whole saga to turn into a wholly avoidable disaster.

EDF has never before experienced such internal revolt. Its chief financial officer Thomas Piquemal quit in March 2016, refusing to approve the venture. For weeks last year engineers, employees and unions produced numerous reports and warnings calling for the work to stop or for the Hinkley project at least to be postponed while EDF finished the construction at Flamanville and assured itself the project could work. They underlined the continuing industrial and financial risks to the board of directors itself, going so far as to remind directors of their personal responsibility in the decisions they make.

It was all brushed aside. Now was not the time to listen to engineers and unions who had years of expertise...the independent directors or state delegates from the French Treasury or Foreign Ministry knew much more about it! In any case the decision had been taken in advance. Before the board could even pronounce on it, the minister for the economy Emmanuel Macron had made clear the verdict when he declared: “Hinkley Point must happen.”

Financial and industrial disaster

At the time of those words, a number of observers wondered about the reasons behind the economy minister's support for EDF boss Jean-Bernard Lévy. Some explained it by the fact that Macron considered Lévy's appointment to head the utility group in 2014 to have been one of his first victories as a minister. The prime minister at the time, Manuel Valls, had wanted Henri Proglio to stay on as CEO and chairman. For Macron, so the argument goes, it was as much a symbolic as political victory: he had beaten the Freemasons on their own turf, as EDF is said to be a Freemason stronghold (Proglio has always strongly denied rumours he is a member). Mediapart understands that this, at any rate, is how Emmanuel Macron proudly presented his success at a meeting with his future election ally and centrist François Bayrou in July 2016.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But beyond that, Macron's stubbornness in supporting the Hinkley Point project can doubtless be explained by a far more important consideration: the need to hide the financial and industrial disaster of the entire nuclear sector and its implications for public finances.

Ever since 2011 the public authorities have known that Areva, caught up in the EPR fiasco and the Uramin scandal, was bankrupt. For several years successive governments tried to hide the truth, until the moment came when such stratagems were no longer enough. In 2014 the nuclear group was on the edge of collapse. The government had a decision to make: either accept the company's bankruptcy and the loss of jobs in rebuilding the group just around mining and nuclear waste treatment or seek to carry on as before while trying to limit the extent of the state bailout. In the end it chose a bit of both.

Areva is now in the process of being dismantled and returning to the core activities of mining, fuels and nuclear waste treatment that were the functions of the old COGEMA company, Areva's predecessor. But the government has never acknowledged the group's bankruptcy nor its dismantling. This has the virtue, apart from having to make a politically difficult admission, of avoiding the need to search for who was to blame for this disaster.

But to convince people that Areva still had a future as a builder of nuclear reactors the group needed orders. Yet after the setbacks at Flamanville, and the global concern over nuclear plants after events at Fukushima in Japan, it had no more orders for EPR reactors. That explains the importance attached to Hinkley Point, where two EPR's were to be built. Without those orders it would be impossible to bail out the nuclear group, and impossible to sell the reactor construction part of the business (Areva NP) to EDF for 2.5 billion euros, money that was to be used to refloat Areva itself.

If the EDF president Jean-Bernard Lévy agreed to accept such an arrangement which was manifestly not in the group's interest, it was because it, too, had a secret to hide: the purchase of its British subsidiary, nuclear power company British Energy, for an exorbitant price in September 2008. The circumstances of this acquisition remain hard to fathom. Although it was the only bidder EDF, then headed by Pierre Gadonneix, agreed to up its offer by 20% to 15 billion euros. Even more unthinkable was the fact that the board approved this increased bid on September 23rd, 2008, eight days after the collapse of Lehman Brothers - in other words, just at the moment of maximum stock market turmoil and where the financial outlook was completely unclear. That deal duly went ahead.

Years later, people familiar with the case still puzzle over the inexplicable nature of this purchase, with some going so far as to wonder if, as one put it, “this operation isn't hiding a scandal comparable to that of Uramin”. Oddly, France's audit body, the Cour des Comptes, which is usually so particular over the managing of public money, has never really studied this purchase. Yet the sums of public money at the time were as large as those criticised by the Cour des Comptes this summer when it said that spending under the last administration had got out of control.

This 2008 purchase has left visible traces in EDF's accounts. More than 8 million euros in overvaluation has never been depreciated. For to do so would mean acknowledging the error of the acquisition and in particular EDF's greatly worsened financial situation. It would have meant admitting that the new business was loss-making and that its capital had melted like snow in the sun.

To hide this error the public utility group, in agreement with the authorities, claimed that the former British Energy had a great deal more value than foreseen, as it was going to build EPRs at its British power stations. To make the project irreversible, EDF's boss in Britain Vincent de Rivaz agreed to more than two billion euros worth of business at Hinkley Point before the board of directors had even given their views. EDF had to move the project ahead quickly to avoid having to reveal the painful truth of their accounts.

The French government not only agreed to cover all this but also to hide the financial reality of France's nuclear flagship. For otherwise it would not have had to pay out five billion euros to bail out Areva but seven or eight billion euros instead. As for the four billion euro recapitalisation of EDF itself in March 2017, three billion of which was underwritten by the state, the figure would have been double that without the Areva arrangement. That was out of the question for a government seeking to keep its deficit down to below 3% of GDP. In this context it is easier to understand why Emmanuel Macron went on to defend the Hinkley project at any price, even if it meant leaving it to his successors the task of dealing with the consequences.

The boomerang effect

It didn't even take nine months for Hinkley Point to come back like a boomerang to Emmanuel Macron's desk. In charge of carrying out the first evaluations, the internal EDF teams quickly grasped that the majority of the project forecasts were erroneous. EDF management now acknowledges a delay of 18 months but internally the estimates of the construction delay are already more pessimistic, Mediapart has learnt. To take just one example there is no longer an existing reactor pressure vessel (RPV) – the part which contains the reactor core – for the EPR at Hinkley Point. The one earmarked for Hinkley was instead sacrificed for tests for the French Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN), to evaluate the RPV at Flamanville. Because of the loss in Areva's know-how in making such vessels at its factory at Le Creusot in central-eastern France, a new RPV can now only be forged in Japan. According to estimates it could take between three and five years to get a new one made.

EDF also admits that the project will cost 1.8 billion euros more than initially forecast. Again, according to Mediapart's information, internal evaluations estimate the extra cost to be be more in the region of 2.5 billion to 3.5 billion euros. And those are only the initial evaluations.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

These difficulties could be just the start of a long series of problems. In their letter to EDF management and the government in 2016 the group's nuclear engineers highlighted the risky industrial nature of the British EPRs. “The model that is planned to be built at Hinkley Point (which we call UK EPR) has over time become one of extreme complexity,” they said.

According to the engineers there are two reasons for this. First of all, the work at Flamanville has revealed numerous conceptual errors which have had to be remedied. The engineers claim they are steering blind on the project all the time the French EPR itself is not in production. The second reason is that the British nuclear safety authority, the UK Office for Nuclear Regulation, has called for numerous modifications, including some linked to the control and command system, the power station's “nervous system”, they say. “So, to put it mildly, the UK EPR model will be a new hybrid and complex production model, consequently bringing with it a high level of risk,” they concluded.

In other words, EDF is having to develop a new hybrid for Hinkley. In the face of such warnings, the call from Bruno Le Maire for a “rigorous plan of action” shows how far removed he is from the realities of this industrial project. It's not analogous to the mass production of cars where one can apply economies of scale.

In light of the difficult experiences with Flamanville and the EPR being built in Finland, the risks seem enormous and are starting to worry EDF staff more and more. This concern is increased by the fact that the group does not appear to have learnt lessons from the past. “The Escatha report [editor's note, written at the end of 2014 by a former top official at France's atomic energy commission, the CEA, to evaluate the risks of the Hinkley Point project, and never published] had in particular recommended a complete change in the organisation of the EDF and Areva teams, to manage the project better,” says an EDF executive today. “But nothing was done.”

It is not just the group's employees who are worried. At the end of June Britain's National Audit Office (NAO) wrote an initial report on Hinkley Point. Its conclusions are alarming. The NAO said that the deal had “locked consumers into a risky and expensive project with uncertain strategic and economic benefits”. The report said that British government ministers had not examined other ways of funding the power station to get the best deal possible, saying government officials expect it to add up to 15 pounds to annual electricity bills by 2030. And it, too, highlights the concerns over technology and the financial strength of EDF. “The reactor design … is unproven and other projects that incorporate it are experiencing difficulties. Furthermore, EDF’s financial position has weakened since 2013,” it notes. The NAO urges the British government to establish and update a 'Plan B' in the event that the Hinkley project is “delayed or cancelled”.

A number of British Parliamentarians, already worried about the Hinkley scheme, are thinking more and more about whether it should indeed be cancelled, at a time of uncertainty over Brexit and falling prices for renewable energies. On one day in the spring of this year British electricity was produced entirely by renewable sources, the first time this has happened.

Scrapping the project is also what many executives and employees at EDF want to happen. Now that that EDF management itself has just admitted some initial delays, which staff say confirms their fears, they want the scheme stopped immediately. They argue that whatever the costs of doing so, it will still be cheaper than the current irrational headlong rush. So far Emmanuel Macron has chosen to brush aside any difficulties. But he can no longer claim that he knows nothing about them.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter