A decision by French investigating magistrates last week that neither Air France nor Airbus should stand trial for their responsibility in the crash of an Air France A330 plane over the Atlantic Ocean in June 2009, in which all 228 passengers and crew on board were killed, has outraged relatives of the victims and other civil parties to the case, prompting accusations that the investigation had buckled before “the aeronautical lobby”.

The Airbus 330 was flying overnight to Paris from the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro on June 1st 2009 when, just more than three hours into the flight, a series of technical incidents led the crew to lose control of the aircraft as it encountered a storm over the ocean. The disaster remains the deadliest in the French carrier’s history.

Both Air France and the aircraft’s manufacturer, Airbus, had originally been placed under investigation – a legal status that is one step short of charges being brought – in the judicial probe for suspected “involuntary homicide”. The investigating judges, who are independent, had received in July a recommendation in July from the Paris public prosecutor’s office that the case against Airbus should be dropped, but that Air France should stand trial. But the investigating juges decided in their final ruling, announced on September 5th, that both Airbus and Air France will not be pursued, against the view of the prosecution services, who on Monday lodged a formal appeal against the decision.

Relatives of the crash victims, who are civil parties to the case, are also lodging an appeal in the hope of re-opening the investigation.

“This decision is an insult to the memory of the victims, taken by a justice system under orders, under the influence of Airbus and the aeronautical lobby,” said Danièle Lamy, whose son died in the crash and who heads an association, Entraide et solidarité AF447, which represents relatives of the victims. “We are going to lodge an appeal and we count on obtaining a trial,” she added.

In their announcement on September 5th, the two examining magistrates in charge of the judicial probe, judges Nicolas Aubertin and Fabienne Bernard, argued that “piloting errors” by the crew of flight AF447 were solely responsible for the crash.

The main French pilots’ union, the SNPL, which is a civil party to the case, described the magistrates’ decision as “scandalous”, adding that it was taken “despite” the accumulation of evidence “against Airbus just as also against other protagonists”.

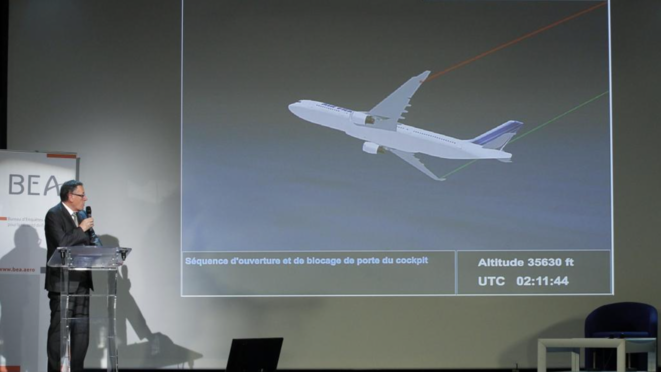

The A330 airliner plunged into the ocean from a height of 38,000 feet after entering into an aerodynamic stall as it crossed through a storm at a point between north-east Brazil and the African continent. The “black box” flight recorders were eventually retrieved from the seabed almost two years later, in May 2011. Crucially, a 2012 report by the French aviation accident investigation body, the BEA, found that the plane’s three pitot speed sensors had iced over as it passed through the storm.

The ice crystals that blocked the pitot tubes, manufactured by French company Thales, caused havoc with the A330’s automatic pilot system, which would normally ensure that the plane did not enter into a stall, and which then disengaged. Pilots do not usually fly manually through the conditions met by AF447 that night, whose three-man flight crew, it has been established, were surprised and confused by the numerous alarms that were set off in the cockpit.

In the report of their conclusions on September 5th, the examining magistrates described the loss of control of the plane as being due to “inappropriate actions” by the captain and “insufficient surveillance” by a co-pilot. By raising up the nose of the aircraft instead of dropping it, the plane ended up stalling. The investigation found that they were unable, in increassingly desperate circumstances, to recognise the source of the problem nor why the plane was falling in altitude, despite the sounding of an alarm which warned of the stalling over a period of 54 seconds.

The magistrates also underlined what they called “serious misfunctioning of coordination between the crew”, and the fact that the captain, who had gone for his rest period in a cabin behind the cockpit as the plane approached the storm turbulence, did not immediately return to the controls after his co-pilots asked for his help.

The judicial investigation found that neither Air France nor Airbus had any responsibility in the state of confusion in which the crew found themselves, nor with regard to the key issue of the icing of the pitot speed sensor tubes, which set off the train of events that ultimately led to the crash.

But for former Air France captain Gérard Arnoux, who flew A320s for the airline and headed its second-largest pilots’ union, the icing of the pitot tubes is “the direct cause” of the disaster. Arnoux, who authored a book about the crash, Le Rio-Paris ne répond plus (The Rio-Paris is no longer answering), published in France in July, acts as a voluntary technical expert for associations representing French victims of aviation accidents. In his book, subtitled “AF447, the crash that should never have happened”, he details what he regards as the failures and errors of Air France and Airbus apparent before the crash. These include faulty pitot tubes, the failure to react to earlier incidents, a lack of proper training of flight crews and sometimes maladapted procedures. “All the necessary information was available since a long time, but it was ignored and underestimated at every level”, he claims, arguing that the crash of AF447 could therefore have been avoided.

A number of the problems highlighted by Arnoux were recognised in the accident report by the BEA, and also in expert studies commissioned by the judicial investigation. However, the examining magistrates concluded that none of these justified criminal charges, either because the regulations in place were respected, or because the decisions taken by Air France and Airbus were validated by aviation safety agencies.

The judges wrote that, “this accident is manifestly explained by a string of elements that had never [previously] occurred and which brought to evidence dangers which could not have been recognised before”. But numerous facts that emerged in the investigation case file, which Mediapart has obtained access to, demonstrate quite the opposite.

- A discarded report

As first revealed by French daily Le Parisien, on August 8th this year the victims’ families association Entraide et solidarité AF447 submitted to the judicial investigation a damning report about the Thales AA pitot tubes, which the association had received from a source that remains anonymous.

The report centres on a comparative test carried out by Thales in November 2004 between its AA pitot tubes and those of its US competitor Goodrich. The Thales AA tubes were shown to suffer strong corrosion after 10,000 flying hours, a condition that hampered effective heating of the instruments – and therefore exposed them to icing – while those of Goodrich suffered little corrosion over the same period. The Thales pitot tubes on flight AF447 had, by that night of June 1st 2009, notched up around 18,000 flying hours.

The report in question recommended that Thales conduct technical modifications to the tubes, which were in fact carried out for a new model, called BA, that was marketed in 2007. Airbus, however, chose to maintain the AA tubes in service, which the victims’ families’ association says was despite the fact that the aircraft manufacturer “in all likelihood had knowledge” of the 2004 report.

Yet other technical reports cited in the judicial investigation detailed the corrosion problem with the AA tubes. In the year preceding the crash of AF447, Airbus had been alerted by airlines, and Air France in particular, to a rise in incidents of the tubes icing over. Shortly after the crash, it was decided that the Thales tubes should be replaced by those of Goodrich, officially described as a “precautionary measure”.

But the French examining magistrates concluded that in the weather conditions that met flight AF447, the Goodrich tubes would also have been subjected to icing. That conclusion was based on a test carried out in a wind tunnel by Airbus – at the very same time that it was placed under investigation – and was made without any opposing expert opinion.

- An underestimated danger?

During the course of 2008 an increasing number of incidents of icing of the pitot tubes were reported, notably by Air France but also by Air Caraïbes, a French airline serving destinations in the Caribbean. For Air Caraïbes, the problem was serious enough for it to alert the French civil aviation authority, the DGAC, in September 2008, when it asked the DGAC if it planned to make replacing the tubes a legal requirement. An official safety agency, the OCV, made up of aviation experts whose mission is to advise the DGAC, recommended that compulsory corrective measures for the problem be implemented.

The DGAC passed on information about the problem to the European Union’s European Aviation Safety Agency, EASA, which in turn consulted Airbus. In March 2009, just two months before the crash of AF447, the EASA adopted the advice from Airbus that there was no need to take action over the incidents of icing of the tubes.

The examining magistrates concluded that the decision was justified, given that the EASA had classified the problem as “major”, a terminology which in fact placed it in second position on a scale of four, and that the number of icing incidents that were reported at the time did not exceed a limit that was allowed for “major” technical failures of the kind.

However, the civil parties to the French investigation argue that Airbus underestimated the problems exposed by the icing incidents which, they say, should have been classified under the more urgent category of “dangerous” and which would have made replacing the pitot tubes a legal requirement as of November 2008.

European-wide regulations set out that the in-flight loss of all information about an aircraft’s speed is indeed “dangerous”. Airbus itself implicitly recognised this when, in 2001, it ordered the replacement of an earlier type of pitot tube. Meanwhile, Thales, the French company which manufactured the pitot tubes which equipped flight AF447, warned in an internal company document that the loss of flight speed data “could be a cause of crashes”. But the EASA was convinced by Airbus to place such incidents in the lower “major” category, notably because it claimed pilots had at their disposal appropriate procedures to deal with the problems for which crews received “adequate training”.

But for that claim to be considered acceptable, Airbus should have ensured that those conditions were respected, and two separate reports, one by the French pilots’ union the SNPL and another by Henri Marnet-Cornus, a former pilot with French airline AOM and now a technical advisor for aviation accident victims and their families, argued that was not the case. Marnet-Cornus concluded his report by noting that, “by negligence and/or imprudence, the evaluation made of the risk, before the accident, was insufficient”.

An initial expert’s report for the judicial investigation demonstrated that during incidents of icing of pitot tubes that occurred before the June 2009 crash, pilots failed to apply the recommended procedures because they were unable to identify the problem. In 2008, Airbus recommended that pilots should be trained in the necessary procedures, which was enacted by Air France, but this only involved a loss of speed at low altitude, and no training was envisaged for incidents during high-altitude cruising – which was finally put in place after the crash.

For the examining magistrates, the flight crew of AF447 had failed to apply procedures they had received training for, while one of the crew can be heard on the voice recorder announcing to his colleagues, “We’ve lost the speeds”. But both the BEA and the early expert reports commissioned by the investigation demonstrated the difficulty the crew had, like others during earlier such incidents, in identifying from the various alarms set off in the cockpit which was the principal cause of the loss of control of the aircraft.

In a magazine dedicated to safety issues published by Airbus in December 2007, the manufacturer noted: “To identify a dubious speed indication is not always easy: no single rule can be given to identify with certainty all the possible false indications, and the presentation of contradictory information can confuse the crew.”

- The blurred focus of responsibility

In their exoneration of any responsibility for the crash on the part of Airbus or Air France, the magistrates repeatedly argued in their conclusions that the various questionable decisions taken by both companies were validated by the competent authorities. That is notably the case regarding the classification of the degree of danger posed by the icing of the pitot tubes, where the EASA agreed the incidents were “major” and not “dangerous”. Yet in fact it was Airbus which convinced the EASA to adopt the classification. In a note submitted to the magistrates by lawyer Claire Hocquet, representing the SNPL pilots’ union, she dismissed such reasoning by the magistrates as “unacceptable” for its implicit removal of Airbus’s responsibility.

Meanwhile, lawyers for the victims’ families’ association Entraide et solidarité AF447 argued that “by definition, a plane which flies is a certificated plane”, referring to it receiving its airworthiness certificate. They underlined that “not having a technical competence equal to that of the manufacturer” the EASA delegated to Airbus “part of the certification” process. That dependency was brought to evidence in a statement given to the French judicial investigation by Patrick Goudou, who was executive director of the EASA between 2003 and 2013. Goudo told the magistrates that after incidents of anomalies were reported “the analysis […] was not carried out by us, it is done by Airbus”, adding: “Airbus explains to us what its findings are and we decide, along with Airbus, what follow-up to give”. In theory, the EASA could disagree with Airbus’s classification of the degree of danger behind an incident, but Goudou said he could not remember that ever being the case.

It was a similar story with Air France. Based on the findings of expert reports commissioned for the investigation, the public prosecution services advised that the airline should stand trial for failing to provide its aircrews with sufficient information on the problem of the icing of pitot tubes. Following several such incidents during 2008, the carrier simply gave pilots a note about the reports, but which did not remind them of the procedure they should follow to deal with the problem. But the magistrates finally decided to drop the case against Air France on the basis that the French civil aviation authority, the DGAC, had not informed the company about similar incidents occurring in the fleets of other French airlines, which, the judges concluded, reduced Air France’s understanding of the danger of the problem. Meanwhile, the DGAC was not targeted by the investigation, which found that there was no legal requirement upon it to inform Air France of the incidents. In his book, Gérard Arnoux describes the fact that the aviation authorities were not the subject of deeper investigation on the matter as “altogether surprising”.

- How expert reports were modified to exonerate Airbus and Air France

In their ruling that the case against Air France, like that against Airbus, was dismissed, the magistrates accused the civil parties – essentially the victims’ relatives and the SNPL pilots’ union – of not having “clearly” explained “failings that could be regarded as criminal faults”. Yet several documents submitted to the investigation by Entraide et solidarité AF447 and also the SNPL union detailed why they believed Airbus was responsible for “negligence and failings with regard to a requirement of caution and safety as set out in law”. These concerned the manufacturer’s underestimation of the risks of malfunctioning of the pitot tubes, and pilot training on the issue of high-altitude stalling and the use of some of the systems present on Airbus aircraft.

The conclusions of expert reports commissioned by the investigation changed in their interpretations as the probe progressed. The first report by a panel of experts, dated June 2012, underlined what they described as “contributing factors” to the crash for which Air France and Airbus were responsible, including a “deficit of information” given to pilots and ill-adapted procedures for dealing with the problem.

Then, in a subsequent report dated March 2013, prompted by the observations to the first submitted by the different parties to the case, the expert panel concluded that none of the identified failings contravened existing regulations. The experts had originally noted that the dangers of recorded incidents of pitot tubes icing over “was underestimated” before the AF447 crash, but ten months later they concluded that these very same incidents were not of a nature to warn of a “dangerous situation”.

This evolution towards a clement appraisal of the eventual responsibilities of Airbus and Air France in the crash was all the more striking in the final draft a counter-expertise report by commissioned aviation specialists dated October 2018. Several passages from the original draft of the report, including “indirect causes” attributed to Air France and Airbus, were either removed or modified for the final draft, which was signed off after the observations of the different parties to the case. The removed contents (highlighted in the document further below in red) included the key observations: “The characterization as “unsafe condition” of incidents of erroneous indications of speed subsequent to the icing of tubes was not recognised either by the manufacturer nor the by the national and European authorities, whereas it had been in 2001.”

Another observation removed from the final draft read: “A more rapid taking into account of the problems of icing would have contributed to imposing a replacement of the Thales C16195AA tubes with Thales C16195BA or Goodrich 851HL [tubes], even if the performance of the tubes could not allow for dealing with the most severe cases of icing. Furthermore, this would have allowed for better information to be given to airlines and a greater awareness of crews to the problem of icing.”

In the comments added to the final draft, the experts exonerated Air France and Airbus of responsibility in all of the remaining criticisms levelled against them, arguing, variously, that none of these were in contravention of existing regulations, or that the decisions of the two companies had been validated by the authorities.

The final draft also modified the experts’ definition of “indirect causes” of the crash. In the first draft, these were factors “which could have led the crew to lose control of the path [of the aircraft] without being able to correct it”. In the final version, the factors were changed to become those “susceptible to have a link to the inappropriate actions of the crew which led to the loss of the aircraft”.

All of which suggests that Air France and Airbus provided convincing arguments in their observations to the experts, whose report played an important role in the decision by the magistrates to drop the case against both.

- The French justice system's approach to aviation accidents

Perhaps because they were only too aware of the anger and frustration that their decision to drop prosecution against Air France or Airbus would cause among the families of the victims, the investigating magistrates insisted their ruling was one which was dictated by the strict constraints of law.

They insisted that there should be no confusion between the “indirect causes” of the crash as identified in the investigation and those actions which can constitute a criminal offence – which would require them to have been unlawful and to have had “a link with the accident that is certain”.

With their appeal against the conclusions of the magistrates, the civil parties will have a fresh opportunity to argue their case before newly appointed judges. But obtaining a trial will be a major challenge given the restrictive criteria that the French justice system appears to adopt concerning aviation accidents.

That was demonstrated with the case of the 2005 crash of a chartered West Caribbean Airways flight in which all 160 people on board were killed, including 152 passengers from the French Caribbean island of La Martinique. The McDonnell Douglas MD-80 crashed, also for reasons of an aerodynamic stall, in a mountainous region of Venezuela as it travelled from Panama to Martinique. Despite serious evidence of the poor standards of West Caribbean, a Colombian company which went bankrupt later that same year, the French examining magistrate in charge of the investigation into the disaster (under French law, a judicial investigation can be opened in France into the deaths of the country’s nationals abroad) concluded the case without bringing charges.

His ruling found that the technical failings in the build-up to the crash had no certain link to the errors committed by the flight crew. The relatives of the victims of the crash succeeded in their appeal for a re-opening of the investigation in 2018, but this did not include establishing the eventual responsibility of the company or the relevant aviation authorities.

The most striking example of the approach of the French justice system to aviation disasters, and one which is the most similar to the case of AF447, was the crash of an Air France Concorde minutes after take-off from Paris-Charles de Gaulle airport on July 25th 2000. All 109 passengers and crew aboard the flight, and four people in a hotel onto which the plane crashed, were killed. The Concorde had run over debris on the runway during take-off, blowing out a tyre which in turn caused the puncturing and explosion of an underwing fuel tank.

The official investigation into the crash found that there had previously been 67 similar incidents recorded worldwide of Concorde planes suffering tyre blow-outs, of which seven led to fuel tank explosions. It was to emerge that the French aircraft manufacturer Aérospatiale, now part of the Airbus consortium, had even envisaged reinforcing the fuel tanks on Concorde, of which it was joint manufacturer with Britain’s BAC, but subsequently decided not to do so.

The case against both Aérospatiale and the French aviation authorities was finally dismissed on the basis that the failure to reinforce the plane’s fuel tanks did not constitute a criminal offence. It was also ruled that the circumstances of the perforation of the tank was different in character to preceding incidents, and was therefore unpredictable.

That was in sum the same reasoning employed by the magistrates investigating the crash of AF447 in their dismissal of the cases against Airbus and Air France. The magistrates argued that despite the numerous incidents and alerts to the problem of the icing of its pitot tubes, the crash is explained by “a series of elements which had never before happened”, and which therefore could not have been recognised in advance.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse