The well-known Printemps department store chain was put up for sale last December. It is part of a large-scale property transaction, now quite common in Paris, where giant investment funds and financiers from around the world fight it out behind closed doors over the rich property pickings in the French capital.

The Printemps store – its flagship store is on the prestigious boulevard Haussmann in Paris's ninth arrondissement - cannot escape this trend. But who will buy it? Its Parisian neighbour and competitor Les Galeries Lafayette, which tried but failed to buy it in 2006, is said to be interested. The Chinese property group Wanda has declared an interest, and investment funds from Qatar have also been mentioned. The sums involved are jaw-dropping, with some buyers allegedly ready to put at least 1.6 billion euros on the table to secure the deal.

It could have remained just another discreet behind-closed-doors high-finance tussle over property, as is often the case. But the battle for Printemps has become more than that. It is an illustration that not only has nothing changed since the financial crisis, but that financial and corporate behaviour has in fact become worse. Greed dominates everything. Some current shareholders of the group are deceiving others. Lawyers and advisers seem to have forgotten about their responsibilities and the law. All is taking place behind the benevolent opacity that is the financial system in the Grand Duchy of Luxenbourg. And ultimately it is Printemps' hapless employees who risk paying the biggest price for the deal.

To understand what is going on today, one needs to go back to 2006. It was in that year that the massive French retail group Pinault decided to sell its controlling share in the Printemps department store group. It was sold to a financial investment group for 1.07 billion euros.

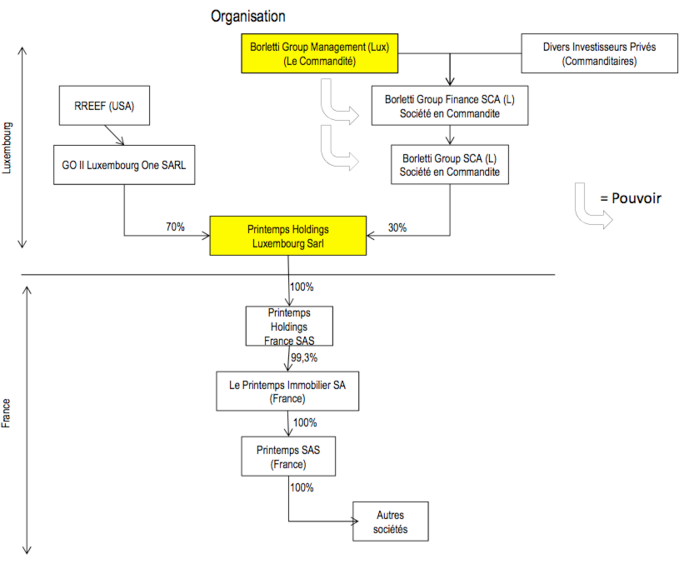

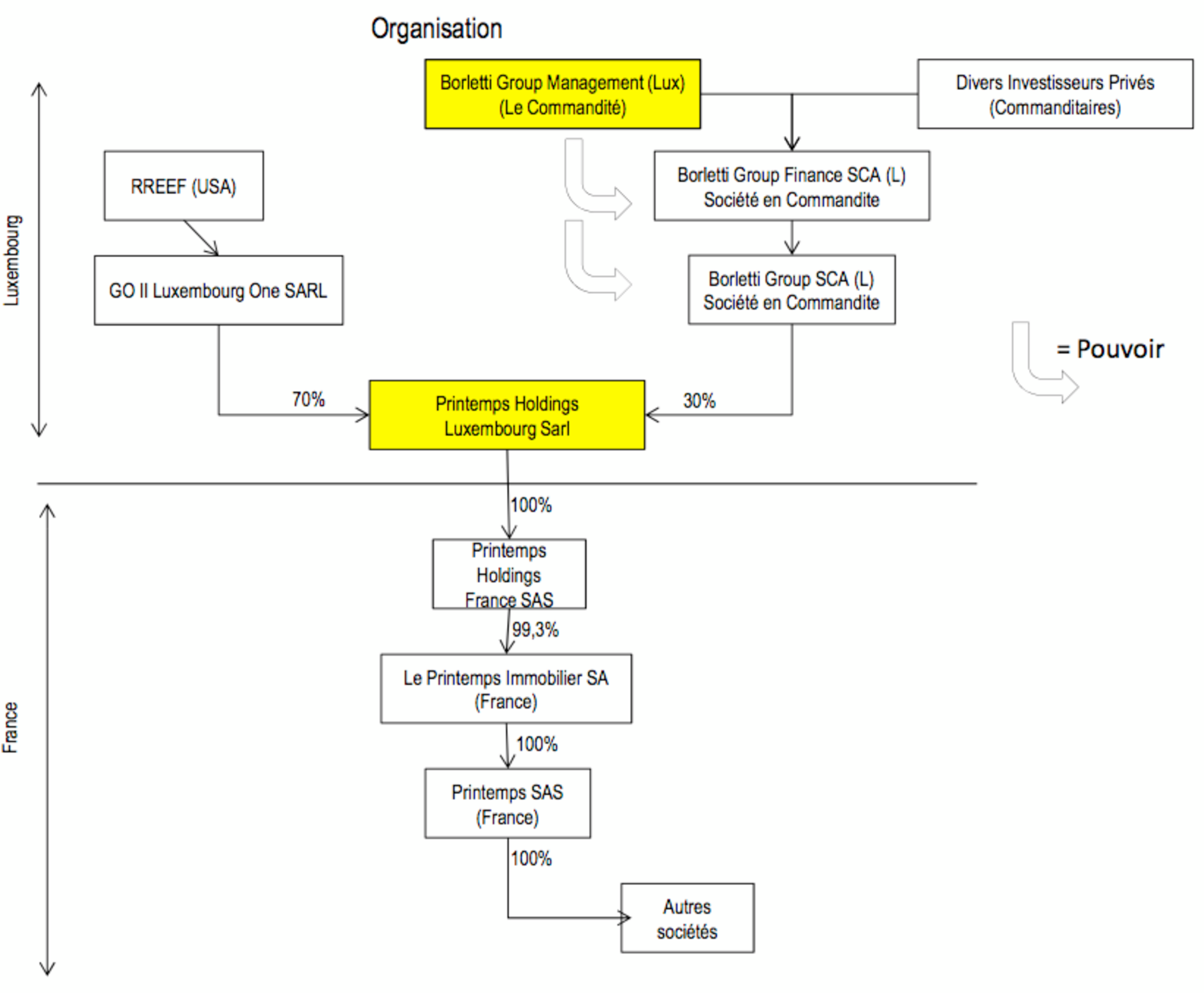

The fund GO II Luxembourg One, part of property investment fund RREEF, a subsidiary of Deutsche Bank, and which brings together institutional investors and pension funds, took a 70% stake in the group. The remaining 30% went to the Borletti Group, a company based in Luxembourg which is controlled by the Borletti family but which benefits from the involvement of other wealthy French and Italian groups, such as Dassault and the Allianz group. The Printemps group itself has been parked inside a Luxembourg-based holding company Printemps Holdings. Two subsidiaries were set up under French law, one to oversee the property side of Printemps, the other to run its commercial retail operation. This is how Printemps has operated for six years, with all the dividends of the group being sent back to Luxembourg.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The property investment fund RREEF has never hidden the fact that its involvement in Printemps was temporary. In past agreements it foresaw selling its share in 2014. But circumstances have led to a change in the timetable. The Parisian property market remains at a high point but many institutional investment funds, anticipating an approaching burst in the property 'bubble' – even though no one uses the term – have already started to sell. Thus for RREEF it seems an opportune moment to sell Printemps at a time when, moreover, there are still purchasers interested and who are ready to pay top prices.

Secret pact

Officially the other owner, the Borletti Group, is not selling, and says it wants to stay with the department store chain. One of its spokesmen points out that the shareholders' agreement gives it the right of first refusal to buy the shares owned by RREEF. And it intends to use it. According to Mediapart's information, the Borletti Group has already offered to buy the 70% share of the Printemps chain for 610 million euros, an offer that was rejected as too low. New negotiations have taken place and the Borletti Group is thought to have increased its offer to around 650 million euros.

To help finance the purchase senior executives at the Borletti Group say they are looking for new investors who, preferring to remain discreet, will be represented by the bank Crédit suisse.

That, at any rate, is the official version given to other Borletti Group shareholders, to the RREEF investment fund and which will doubtless be given to the management and staff at Printemps.

The reality seems a little different, however. While a spokesman insists that “the Borletti Group is absolute not selling”, it has already prepared a plan to sell all the shares to the company French Properties, a subsidiary of the Dutch investment fund Mayapan, which is personally owned by the Qatar Sheikh Al Thani. The Borletti Group spokesman denies the existence of an agreement with that company. And when contacted by Mediapart neither French Properties nor its lawyers responded.

However, as the document in English below shows, senior executives at the Borletti Group, through the offices of their trustee in Luxembourg Jean-Martin Stoffel, did indeed sign an agreement for exclusive negotiations with this property company from Qatar, represented by the law firm Baker & Mackenzie, on December 21st 2012. In it French Properties offers to buy the Printemps Group for 1.6 billion euros, close to eleven times the net operating income, once all the formalities are completed. The sum envisaged in the deal represents a capital gain of more than 500 million euros. This will be tax-free, as everything will be transacted in Luxembourg.

Why so much mystery around exclusive negotiations? In making it appear that they are buying the remaining 70% share of Printemps in order to keep it, in hiding from co-shareholders in Printemps both the identity of the buyer – Qatar being known for its deep pockets – and the sum already agreed, the Borletti Group seem to have the intention of keeping most of the capital gains for itself.

But the little secrets appear to go even further. The senior executives at the Borletti Group also seem to have hidden what they were planning from their own shareholders. They talk to them of potential investors, while the documents that have been drawn up speak only of a single investor. They certainly do not mention Qatar, preferring to highlight the bank Crédit suisse as an intermediary. They don't mention, either, the figure for the sale, with the aim of keeping the maximum amount of the capital gains for themselves. In the internal documents that Mediapart has been able to examine, the executives have carried out simulations: they appear to hope to keep up to 150 million euros – in the best-case scenario – for themselves.

The secrets don't stop there. In exchange for the exclusivity granted to French Properties, the Borletti Group senior executives have obtained conditions so unbelievable that they could almost resemble corruption.

French Properties have, in fact, granted the Borletti Group senior executives an incredible annual 'management fee' of 1% of Printemps' turnover. This is supposed to represent fair reward for their involvement in the running of the department store chain. The principal mission of the senior executives of the Borletti group – there are three of them - is to ensure that the decisions taken by the board of directors are put in operation by the real management of Printemps.

Moreover, after a period of seven years, the senior executives will be granted profit sharing of 20% calculated according to one sole criterion – the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization and rent or EBITDAR. This kind of formula is similar to the profit-sharing given to managers of capital investment funds. But the difference here is that the Borletti senior executives are not investing in the business. A noteworthy fact is that, according to the signed agreement, this bonus will be paid if the agreement is terminated before the end of the contract period (see the terms of the management agreement in English here). The fact that none of the - many – consultants who surround this deal winced at seeing such arrangements says a great deal about the state of greed that has overtaken the world of finance.

Financial predation and workplace devastation

In November 2012 the Borletti Group drew up an ambitious development plan for the Printemps Group. Putting to one side growth in demand among their usual French customer base, which according to them was only going to stagnate at best, they banked on strong growth in international customers after the repositioning of the department stores. Referring to their own figures, the payment of 1% of the turnover could give them at least 15 million euros a year, meaning more than 100 million euros over seven years. In French law this level of compensation comes close to a misuse of company assets. But that seems not to have worried the lawyers who drew up the agreement.

As for the profit-sharing, if one sticks to their forecast of an operating income of 250 million euros in 2017, that would bring them a profit share of 280 million euros, which is a huge sum. One now understands better the great discretion of the Borletti Group senior executives over the secret agreement signed with the Qatar investment fund and its perks.

So as not to reveal the details of their project, the Borletti Group has drawn up a four-stage battle plan (see document below, in English).

The first step is for Borletti to buy the 70% of the Printemps shares owned by the RREEF fund, and to ensure that the lines of credit are in place to oversee the running of the business. This is to be funded by the “investor”, meaning the Qatar-owned French Properties.

In step two Borletti Management, the subsidiary of the Borletti Group that has the profit-sharing contract linked to Printemps, is de-merged. All those parts which are not involved with Printemps are “hived down” into a new entity. In step three French Properties buys the Printemps shares from the other shareholders. Finally, in step four the senior Borletti Group executives – who are at this point joint owners with French Properties – in turn sell their Printemps shares to the Qatar fund, probably at a higher price than the other shareholders because they can claim they are selling their management role. This is despite the fact that they have meanwhile negotiated a new and extraordinary management agreement, as described earlier.

According to Mediapart's information, the Borletti Group's senior executives could earn a minimum of 500 million euros by the time the entire deal has run its course. It is a huge and puzzling sum, especially given that it would be earned in the context of a sector – retail department stores – where profitability is quite low.

This financial predation will have a cost, and a cost that will have to be borne elsewhere. The evidence suggests that the burden will fall on the workforce.

For French Properties is certainly intending to recover its stake quickly. According to Mediapart's information, its plan is to transform the Printemps department stores - at least those at boulevard Haussmann in Paris, those in the province seem likely to be sold off – into a huge luxury retail area. The Qatar investment funds have great ambitions in this niche market. In this type of store it is the brands themselves who employ the staff on the ground, with an employment status likely to be fairly insecure.

There will be few or even no staff working directly for Printemps. A large number of the chain's staff, who nonetheless agreed to major efforts to keep their shops going (working in the evenings, opening Sundays, salary controls) are therefore under threat. There will inevitably be talk about the high cost of employing staff in France, of the way French employees have not adapted to globalisation. But what will be said about this financial devastation carried out for the benefit of just a handful of people?

----------------------------

English version: Michael Streeter