The cité Lesage-Bullourde, the foundations of which were reportedly first laid at the end of the 18th century with stone from the then recently demolished Bastille prison nearby, during the French Revolution, was a small, dilapidated site of inhabited buildings and workshops that, because of their insalubrity, were finally razed to the ground in 1961.

The destruction of the Cité was first envisaged in 1917, during the First World War, but was definitively ordered in 1957, during the Algerian War of Independence. In between was the Second World War, and with it the German occupation of France.

A number of European towns and cities have kept the memory and scars of the Hitlerian times. That was, up until recently, the case of the Hungarian capital Budapest where, in the dilapidated historic Jewish quarter, Erzsébetváros, the stairwells seemed to still echo to the sound of rifle butts on the landings.

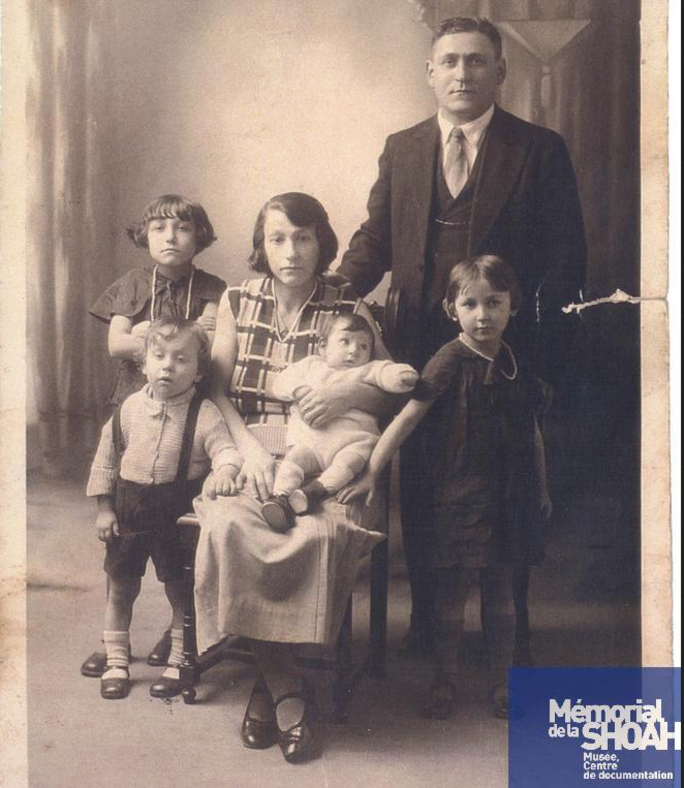

In Paris, the cité Lesage-Bullourde had remained in its miserable state by the force of things, the unchanged setting of recent abject events. The black and white photos which illustrated a 1958 doctoral thesis on the inhabitants of the Cité, by Jean-François Théry, a student at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (now known as Sciences Po), who later became a member of France’s Council of State, present an accursed site where, some 15 years earlier, its Jewish inhabitants were rounded up and deported to German death camps.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

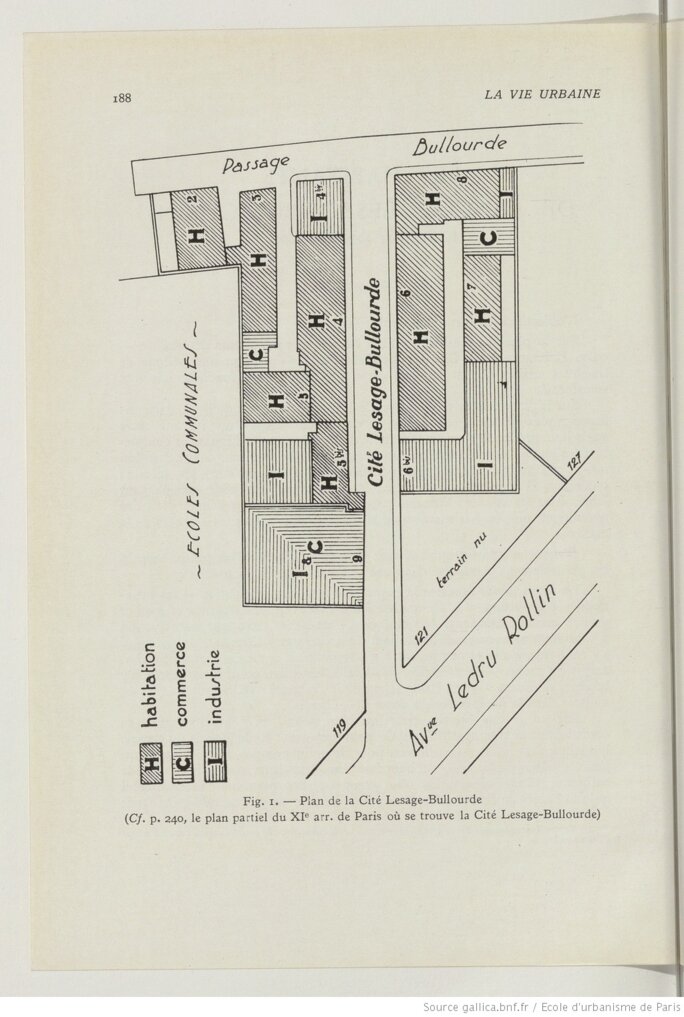

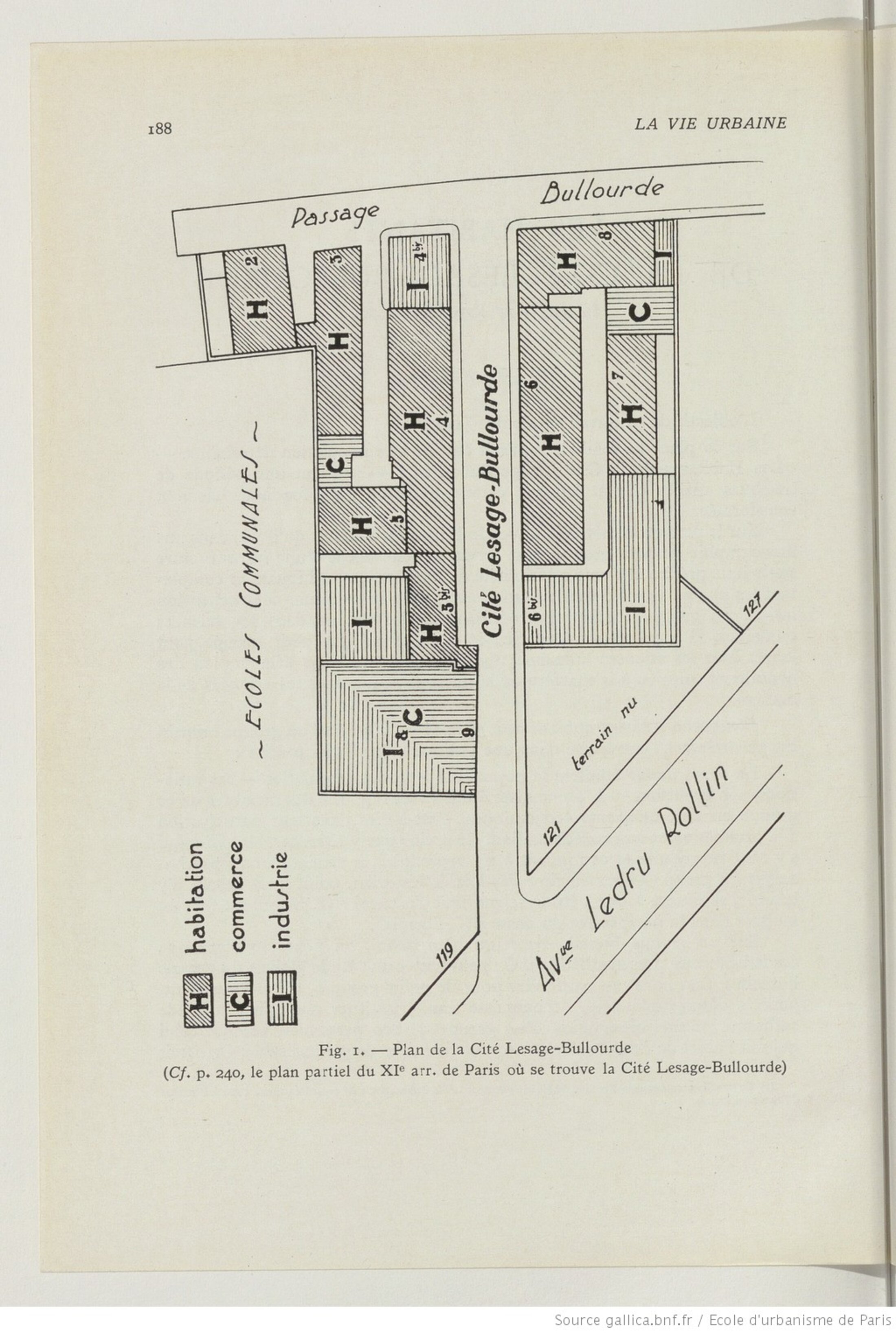

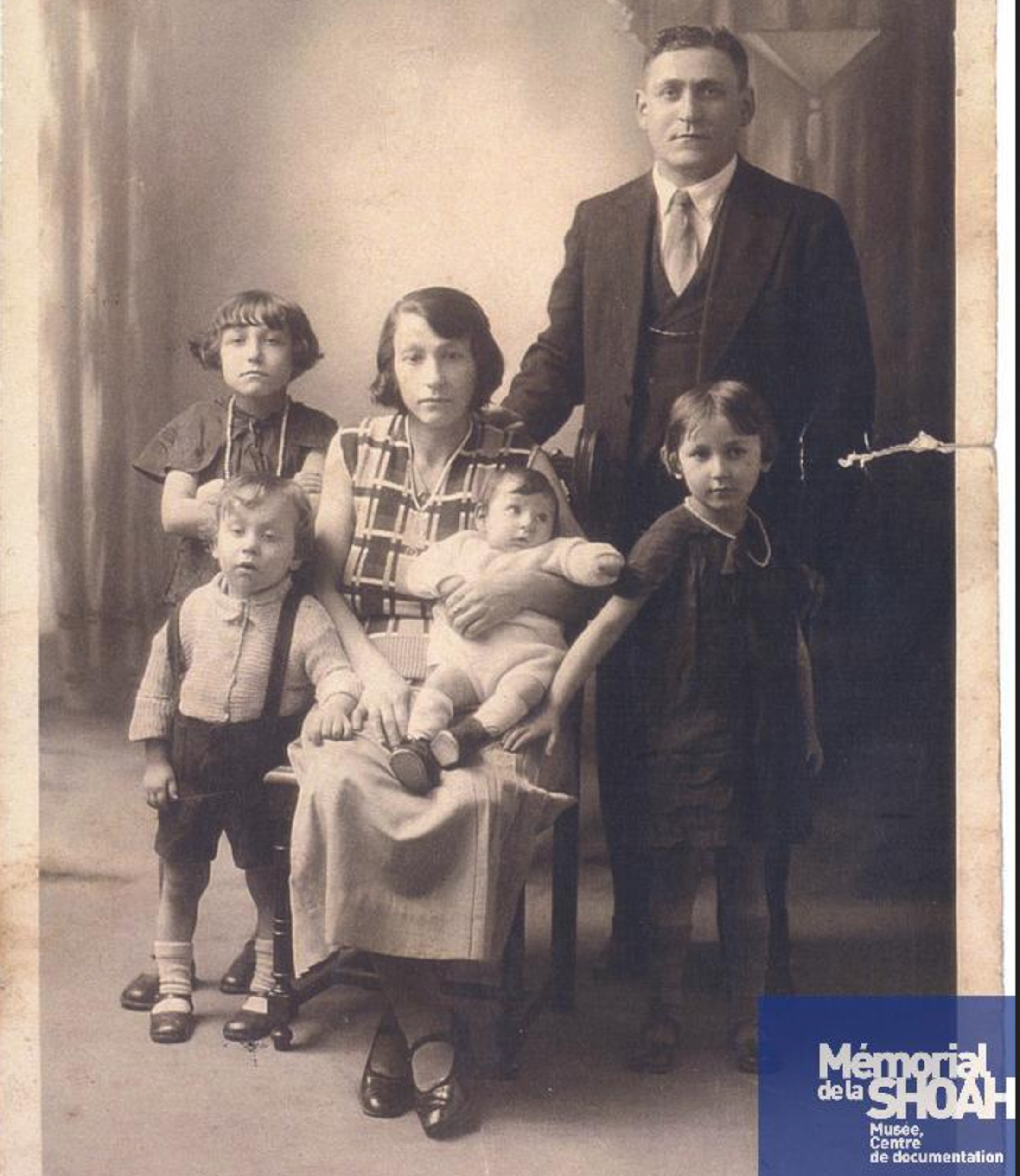

The inhabited buildings and adjacent workshops of the cité Lesage-Bullourde lay on either side of a single, stone-paved road. In the early 1940s, the Cité’s inhabitants numbered around 500 adults and children. They were poor families, many of them numerous, squeezed into small apartments of one or two rooms. They included Jews who had fled anti-Semitism and misery in central Europe and, beginning in 1933, the terror of the Nazi regime in Germany. Between the two world wars, they were often regarded in France with, at best, pity – that is, compassion tinged with contempt – and, at worst, sarcasm and hate.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

An article published on June 30th 1928 in the Parisian daily Le Petit Journal bears witness to the attitudes towards this population, ridiculed for their supposed, if not invented, mores, their religion targeted with mockery, their language scoffed at. The article is by-lined Georges Martin, and is an account of the first day of the trial of a man accused of murdering another in the cité Lesage-Bullourde, described in the headline as a “ghetto”.

Mordka Liwerant, a cabinetmaker, was standing trial for stabbing to death, with a pair of scissors, Abram Waysbaum, a tailor. The reporter, using an ironic tone, wrote: “One believes that these statements were made in Yiddish. It’s the only language that is in current use in the cité Lesage, the only one that the accused speaks perfectly, as also most of the witnesses. The interpreter had his work cut out, all the more so because Liwerant and several of his contradictors have minds finely tuned by the subtilities of the Talmud.”

The reference to the Talmud which finely tunes minds was a sly quip, intended or thoughtless. Racism fuels a criminalization of difference and justifies, a priori, the assassination of the Other, considered to be preventive, and this 1928 article prepared people’s minds for the worst, which would arrive following the Wehrmacht’s crushing of the French army in 1940.

Infamy would soon follow. In what became known as the “rafle du billet vert” (the green ticket roundup) of May 14th 1941, close to 6,700 foreign Jews in the French capital were issued by police with a summons, printed on green-coloured paper, ordering them to present themselves to the authorities, accompanied by a family member or friend, for a verification of their “situation”.

The recipients were variously designated one of five centres around Paris where they were to arrive that May 14th at 7 am, together with proof of their identity. In the event, the more than half who complied – believing the operation to be an administrative formality – were immediately detained, when the person accompanying them was given a list of essential items to fetch and bring to the holding point. These included blankets and a bedsheet, a bowl and a glass, and food “for 24 hours”.

For those in the Roquette district of Paris, in which the cité Lesage-Bullourde lay, the centre indicated on the green ticket was the Japy gymnasium. Like for all the others rounded up in the capital that day, they were then taken by train to internment camps in the Loiret département (county), at Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande, about 100 kilometres south of Paris. Frome there, beginning in the summer of 1942, they were deported to the concentration and extermination camp complex of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In its edition published on May 19th 1941, the notorious French anti-Semitic and collaborationist weekly Je suis partout (meaning “I am everywhere”) exulted in this first roundup of Jews carried out by France’s Vichy regime at the demand of the German occupier. “The French police has at last taken the decision to purge Paris and to render harmless the thousands of foreign Jews, Romanians, Poles, Czechs, Austrians, who, for several years, have carried out their business to the detriment of ours,” it proclaimed, adding, in racist and mocking rhetoric: “The people from the ghetto, who are not without a nose for things, believed in a simple verification by the police.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It was just the beginning. By 1944, a total of 99 Jews from the cité Lesage-Bullourde had been arrested and sent to extermination camps, representing around a fifth of the pre-war population of this compact site.

French historian and lawyer Serge Klarsfeld has for most of his life been engaged in militant action for the documentation and proper recognition of the events of the Holocaust. With his wife Beate, who was born in Berlin in 1939, he spent several decades, beginning in the 1960s, tracking down and exposing untried Nazi criminals and their collaborators, and he is the president of an association called Fils et filles des déportés juifs de France (FFDJF) – for “sons and daughters of the deported Jews of France” – of which the 87-year-old, whose Romanian Jewish father died at Auschwitz-Birkenau, is one.

In the late 1970s, the association began publishing a list of names of the more than 37,000 Jews who were deported from Paris during Nazi occupation. These were presented by the code numbers of the train convoys that the deportees were transported on. In 2012, to avoid the confusion that could be caused by namesakes, Klarsfeld updated the list of names of deportees in a format that presented their addresses in alphabetical order first, followed by last and first names and their ages.

Mediapart consulted the 2012 list at the Mémorial de la Shoah, a centre dedicated to the history of the Holocaust, with exhibits, a library and archives, situated on the rue Geoffroy l’Asnier in the Marais district of the French capital. The list revealed that among the deportees from the cité Lesage-Bullourde were 58 children, aged between three and 18, most of whom attended the separate schools, one for boys and the other for girls, on the nearby rue Keller.

The list of those children follows here, by address, name and age (except where not established). The victims among the Jablonka family, whose fate is detailed further below, are highlited in bold:

2, cité Lesage-Bullourde

WAJNTROB Georgette, 13

WAJNTROB Marie, 10

WAJNTROB Michel, 5

4, cité Lesage-Bullourde

DREZNER Jacques-Pinkus, 15

FAJWISIEWICZ Marcel, 17

FLIGELMAN Annette, 15

FLIGELMAN Odette-Thérèse, 14

JABLONKA Sarah, 16

JABLONKA Abraham, 13

JABLONKA Blanche, 10

JABLONKA Paul, 8

JABLONKA Léon, 6

JABLONKA Rachel, 3

MYSZKINSKI Jacob-Jacques, 14

RYGMAN Berthe-Bina, 13

RYGMAN Jacques, 6

RYGMAN Madeleine, 10

SZAJNFUKS Ginette, 10

SZAJNFUKS Henri, 14

SZAJNFUKS Suzanne-Clara, 16

YOSEF Roger, 18

ZARCON Joseph

ZARCON Juliette

ZARCON Tova

5, cité Lesage-Bullourde

LEIBOVICE Gaston, 13

LEIBOVICE Marcel, 14

ROSENBERG Marcel

6, cité Lesage-Bullourde

AMRAM Jacques, 15

BAJROCH Isaac, 16

BAJROCH Maurice, 17

BAJROCH Valouch-Willy, 12

BUK Louise, 16

DJAMENT Chana, 16

DJAMENT Tauba, 18

IRENSZTEIN Albert-Abraham, 11

IRENSZTEIN Georges, 9

IRENSZTEIN Henri- Israël, 5

IRENSZTEIN Jeanne, 3

IRENSZTEIN Mendel, 17

IRENSZTEIN Nechama-Nicole, 14

LAUFER Esther, 17

RUBINSTEIN Germaine, 17

RUBINSTEIN Jeanne, 16

RUBINSTEIN Maurice, 16

RUBINSTEIN Rose, 14

SZMURMAN Chaskel, 15

SZMURMAN Henri, 10

SZMURMAN Moszek, 15

7, cité Lesage-Bullourde

BABANI Victor, 18

JONAS Beatrice, 7

WEINWOURCHAL Henriette, 16

WULFOWITZ Henri, 16

8, cité Lesage-Bullourde

ALTERMANN Marcel, 8

PIEPRZOWNIK Hélène-Chaja, 14

REDLER Anna, 11

REDLER Celine, 6

REDLER Rywka, 15

SANTER Jacques, 12

At number 4 of the road that runs through the cité lived Nusym et Raïssa Jablonka. Their fate is detailed at the Mémorial de la Shoah. The couple and their seven children all died at Auschwitz-Birkenau after their deportations there during 1942. The first to be deported was the father, Nusym Jablonka, who was born in Poland in 1897. He was taken to the extermination camp by rail convoy “N°12”, while his eldest daughter, Macha (not listed above because of her age), was deported in convoy N°13. Her sister Sarah, 16, was deported on convoy N°16. The remaining five children, the youngest of the siblings (Abraham, Blanche, Paul, Léon and Rachel), were deported along with their mother Raïssa (better known as Rose, and born in Poland in 1901) on rail convoy N°24 on August 26th 1942.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The tragic fate of the Jewish inhabitants of the cité Lesage-Bullourde is, like that of others, listed online by the Mémorial de la Shoah (such as here). To properly trace the stories of so many destroyed lives requires a visit to the institution’s library, where archivists are available to assist research through the maze of documents and also the mess of misspelt first names as recorded by the French authorities or those of Nazi Germany.

Some of the deported Jews from the Cité are remembered in moving online tributes (such as this homage for Szmul Przyszwa, who lived at N°6 cité Lesage-Bullourde, a homage co-written by his three children). But among these tombless dead are others of who there is no trace left on paper or online, remaining phantoms, enigmas. That amounts as a victory for Nazism – the removal of any trace, a nothingness.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

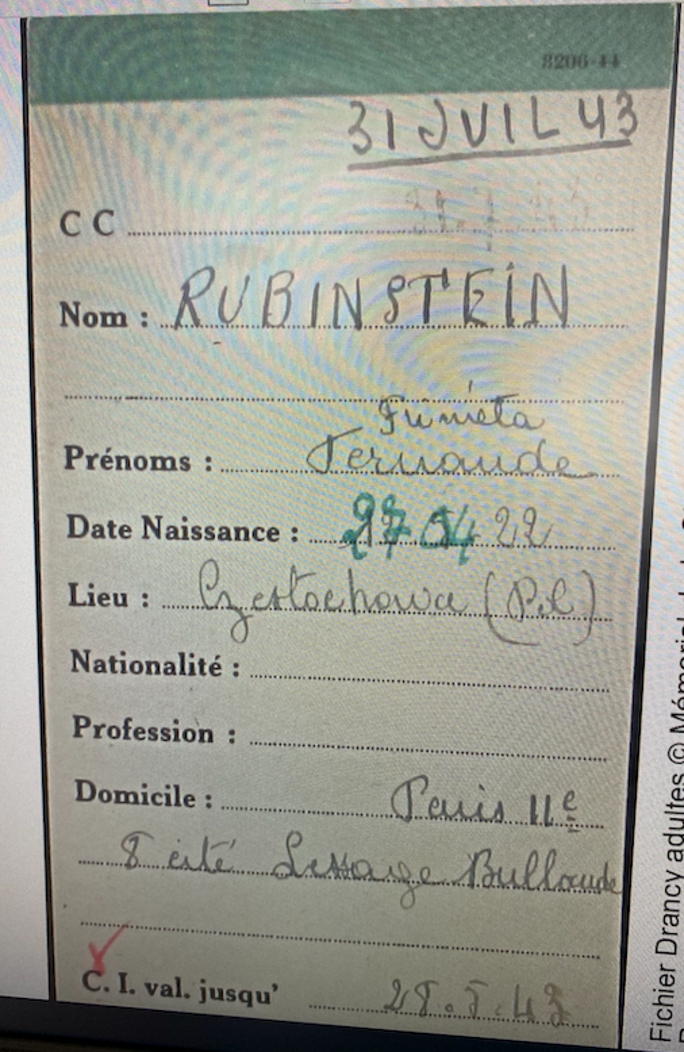

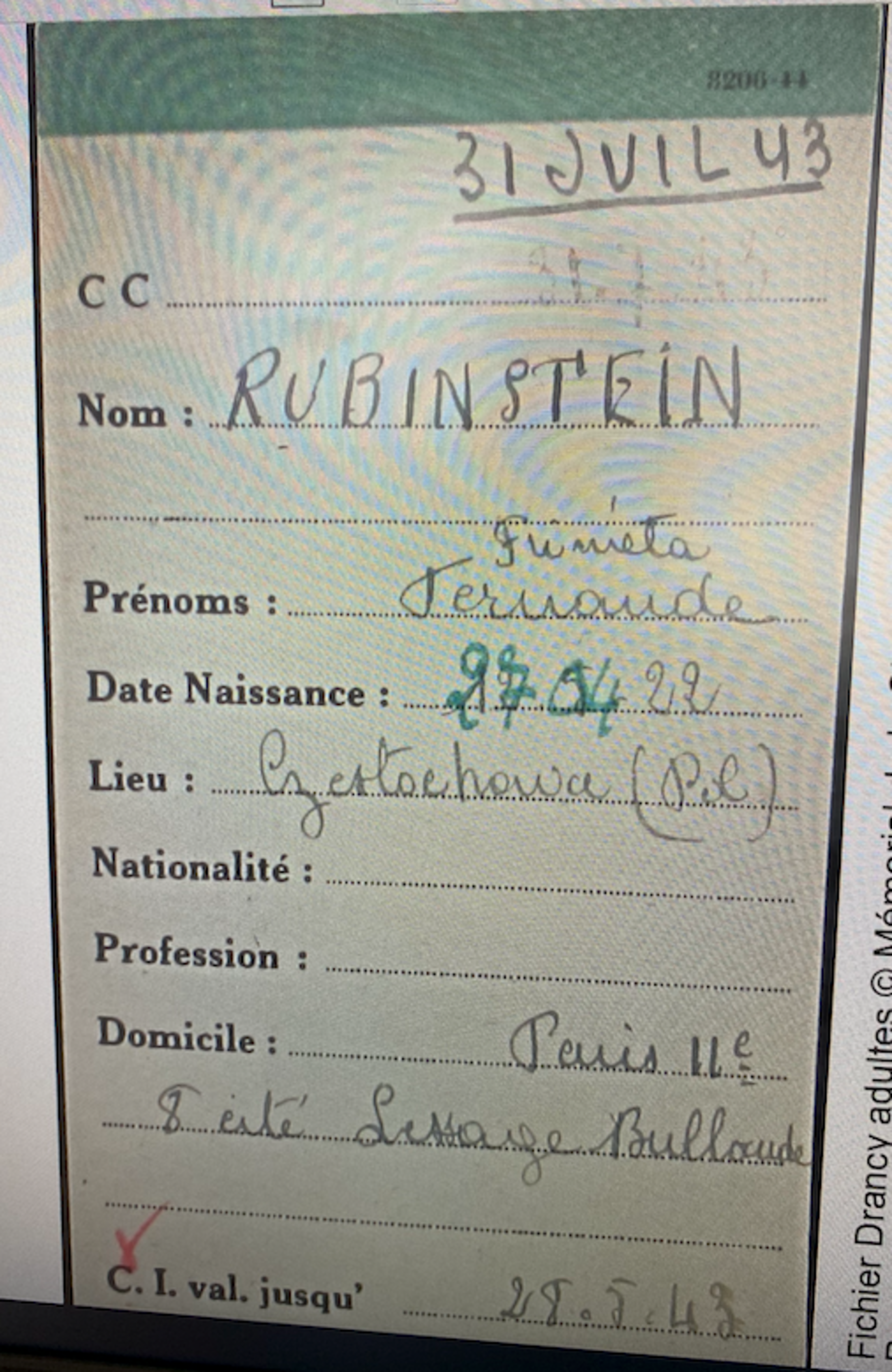

The list of Jewish deportees from Paris compiled by Serge Klarsfeld does not always completely tally with that of the Mémorial, as is the case of four women and girls who also lived at N°6 of the cité Lesage-Bullourde – Fernande (21), Germaine (17), Marie (19) and Rose (14 ) – all from the Rubinstein family. In the Mémorial archives, there is no mention of Rose.

In a detailed article by Julia Winckler on the work of American-British photographer Marylin Stafford and the lives of people at the cité Lesage-Bullourde, which she photographed in the early 1950s, published last year, it is revealed that Germaine and Rose were in fact sisters, and cousins of Marie and Fernande.

Among the archives at the Mémorial de la Shoah is a “fichier Drancy adulte”, which is a list of adults who were taken to the notorious internment camp of Drancy, a small town close to north-east Paris. The camp was where the vast majority of deported French Jews were first taken before being herded onto trains which took them to death camps.

Among the Drancy archives, which can be consulted on computers at the Mémorial, is an official form on the subject of Fernande Rubinstein (pictured), dated July 31st 1943, the day she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On the back of it is written “certificate given to the mother 8-3-45”.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

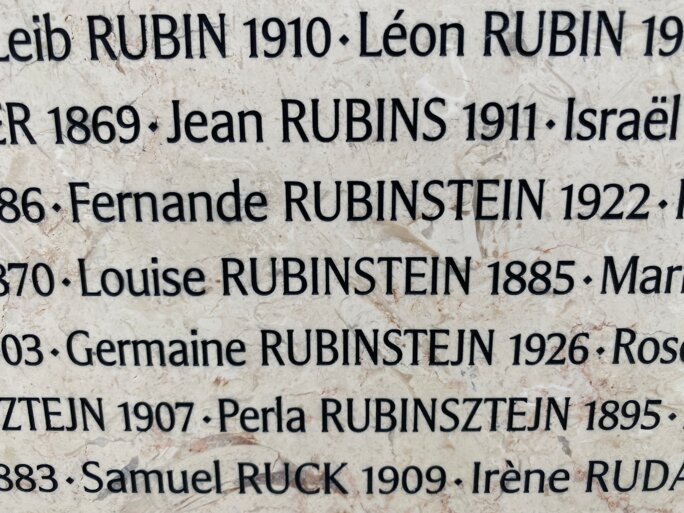

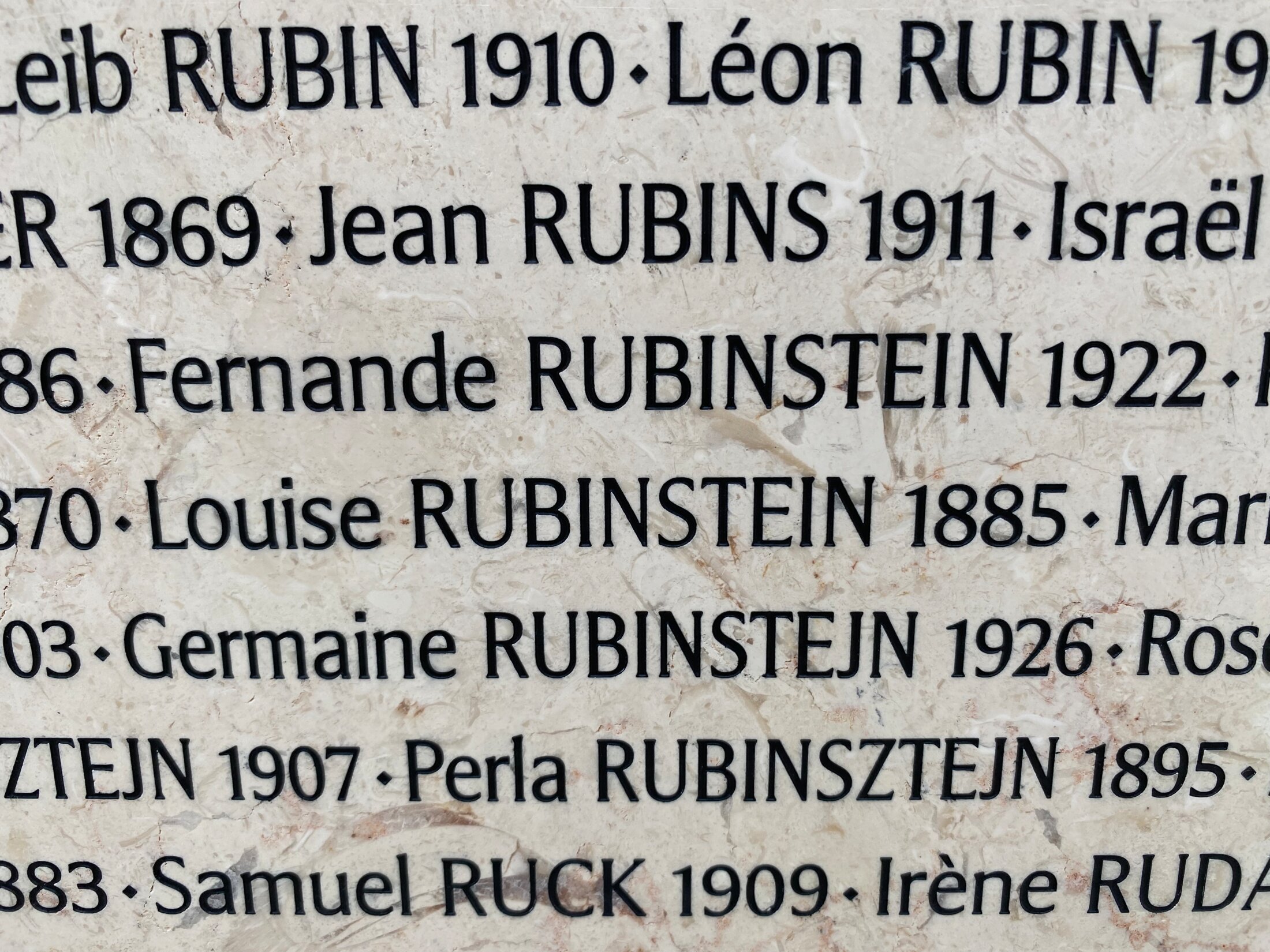

On the Mur des Noms ("Wall of Names") in the courtyard of the Mémorial, Fernande’s name features on row 3, stone number 39, column 13. Hers is one of almost 76,000 names, carved tightly together and seemingly on to infinity. They belong to the Jews recorded to have been deported from France, including 11,400 children, between 1942 and 1944 as part of the Nazi regime’s plan to exterminate the European Jewish population. A plan enacted with the assistance of France’s collaborationist Vichy government.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here. The other articles in the four-part series in French can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse