When French health minister Agnès Buzyn stood down on February 16th, leaving her post in order to stand as candidate for Paris mayor on behalf of President Emmanuel Macron’s ruling centre-right LREM party, she declared that the spread of the Covid-19 virus in France was under control.

While it is now known that the circulation of the virus in the country was in fact rapidly building into an epidemic (and that one case had been mis-diagnosed as far back as December), for Buzyn all was well. “The cases in France have been contained,” she said as she left the ministry, handing over to Olivier Véran, the current health minister. “There are no secondary cases, no new cases since nine days,” she added. Her reassurance proved to be an illusion.

The only testing then for the virus was of people who, showing symptoms of the disease, had recently returned to France from countries considered as hotspots for the coronavirus, notably China and south-east Asia, and the authorities did not believe the virus was circulating within France.

The first recorded death in France from the Covid-19 virus was that of an 80-year-old Chinese tourist, on February 14th. He had arrived in France on January 23rd with members of his family who also became ill but survived.

It was on the morning of February 25th that that reality began emerging, with the death of a teacher from a secondary school in Crépy-en-Valois, in the Oise département (county), about 70 kilometres north-east of Paris. Neither the 60-year-old, nor a 55-year-old man infected by the virus who was hospitalized that same day in a serious condition in the town of Amiens, 80 kilometres further north, had recently travelled to Asia.

A study by the Pasteur Institute in late March would find that what was soon identified as a cluster in Crépy-en-Valois had actually begun in the third week of January (see here, in French).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

According to a confidential report by Santé publique France, the administration responsible for epidemiological monitoring of the population and notably introducing urgent policies in response to exceptional health crises, and which was obtained by Mediapart, an epidemiological investigation launched on March 3rd to find the “patient zero” who was at the origin of the cluster in the Oise failed to identify anyone. But it did identify a chain of infection that linked the Crépy-en-Valois lycée (for the three final years of secondary schooling) and its sister collège (for the early years of secondary schooling) where the deceased teacher worked, in local families and also a military airbase in nearby Creil. But the chain did not stop there; it continued within hospitals and onto other French regions, including Paris and its greater region (the Île-de-France), Occitania in the south-west and Brittany in the north-west.

The Santé publique France report was never published because its epidemiologist authors themselves considered it to be “incomplete”. They wrote that the results of their study “underestimate the extent of the transmission chains, in particular at the beginning of the circulation of the virus, because of the existence, now established, of subclinical forms [editor’s note, before symptoms emerge] of the illness (asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic) which have not been subject to treatment and therefore have not been identified.”

With the apparent impossibility of tracing the presence of the virus back to a “patient zero”, the epidemiologists considered that the interest of such studies is rather to establish where the chains of transmission exist and “the places where they could have been amplified, and the predisposing factors”.

The reason for the wide circulation of the virus in the Oise département was, Santé publique France concluded, because it had been initially spreading for weeks in the secondary schools where it had manifested itself in a non-serious form among the adolescents.

As of the month of February, the novel coronavirus was spreading unseen. The growing wave became what medical professor Frédéric Adnet, head of the Accident and Emergency (A&E) services at the Avicenne hospital in the northern Paris suburb of Bobigny, called “a torrent that swept through our hospitals, when we had [only] set up saucepans to deal with water leaks”. For professor Yonathan Freund, a doctor with the A&E department at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, one of the largest in the capital, “We were in total denial”.

Yet the warnings were there; Freund’s Chinese colleague at the Pitié-Salpêtrière’s A&E service, doctor Na Na, who was in charge of the hospital’s coordination with medical services in China, gave an interview in early February to public broadcaster France inter, when she described the chaos in Wuhan, the city at the centre of the pandemic. She told of how the medical staff lacked sufficient Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to deal with the huge number of cases, and that “they keep their gowns on for six hours, they don’t eat, don’t drink and wear nappies to avoid going to the toilet”.

At the end of February, Éric Caumes, infectious diseases professor at the Pitié-Salpêtrière, and Jean-Michel Constantin, head of the hospital's intensive care unit, compared the new coronavirus to a form of regular flu, expecting no major problems at the hospital. They believed the measures of lockdown on public movement that had been introduced in China and Italy were excessive. “We were wrong about the contagious character of the virus,” admits Constantin. “And China lied about the 3,000 dead in Wuhan.”

“In 30 years of experience, I have dealt with many epidemic alerts, for SARS, the H1N1 virus, MERS-Cov, Ebola” said Frédéric Adnet, of the intensive care unit at Avicenne hospital. “Each time we were prepared and we saw no patients, or very few. So, I had an impression of déjà-vu, the feeling of restarting a cycle, in good mood.” But he also recalled having a few doubts. “Why were the Chinese in lockdown, why were they building a hospital with 1,000 beds?”

Following the death of the schoolteacher from Covid-19 on February 25th, testing for the virus was introduced as automatic practice on every patient hospitalised with pneumonia symptoms. On February 27th, an elderly man in intensive care at the Tenon hospital in Paris tested positive. During his passage in the hospital, he contaminated 40 people. Meanwhile, eight people were tested positive at the airbase in Creil, with the transmission linked to the 55-year-old hospitalised in Amiens. A cluster of cases were identified at the main hospital in the town of Compiègne, also in the Oise département.

At that time, the crisis in Italy was developing, with about 100 cases identified in the north of the country.

On February 27th, when President Emmanuel Macron visited the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, professor Éric Caumes warned: “We have a situation like in Italy, with autochthonous chains of transmission. The virus is already circulating amongst us.” But still he did not take full measure of what was to come. “I see that as the flu virus, which hits fragile people. The problem is the effect of numbers,” he said then.

With hindsight, A&E staff now realise that they had a reliable indicator of the problem in the number of calls made by the public to the emergency services. In the Seine-Saint-Denis département that rings north-east Paris, the calls began climbing as of February 25th.

Santé publique France and the regional health agency network (ARS), who were attempting to trace back on cases, soon saw the situation escape their control. On March 1st, Santé publique France director Geneviève Chêne sent a report to France’s director general of health Jérôme Salomon, in charge of healthcare management under the health ministry, alerting him to an “accelerated spreading” of the virus in mainland France. She referred to 130 confirmed cases, “the appearance of several clusters”, along with “sporadic cases that could not be connected with confirmed cases”, and centres of “active transmission”.

There were by then 12 French regions where the epidemic had spread to. In the three worst-hit of these – the Hauts-de-France (northern France), the Île-de-France (greater Paris region), and the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (in the centre-southeast) – Chêne warned that “the resources engaged in investigating each confirmed case no longer guarantee the identification of all the chains of transmission and the contacts of cases with a view to tracing, and to break the chains of transmission”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Jérôme Salomon appears not to have agreed with Chêne’s suggestion that the situation was no longer under control. The first measures restricting public movement were applied to the Oise département where schools were closed in nine municipalities and public gatherings were banned.

'We were ready for nothing'

Another report by Santé publique France, dated March 6th, shows that the health authorities were prevaricating over whether to declare that the virus spread had reached “stage 3”, meaning an epidemic. There were two reasons for this. One was, as the report noted, that doing so would have “as a foreseeable consequence an important acceleration of the spread of the virus” because there would no longer be systematic tracing of contacts with positive cases “the prime objective of which is to interrupt the chains of transmission”. The second reason was the shortage of testing equipment for which declaring an epidemic would “prompt increased demand for” and which “it will not be possible to meet”, warned Chêne. When, on March 14th, stage 3 was officially announced, the authorities decided that testing would be limited to hospitalized patients with symptoms of the virus, and to healthcare workers.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“At that time, we still had the idea that the tests served above all in getting a good idea of what was happening on the ground,” said Antoine Flahault, head of the World Health Institute at the University of Geneva, in Switzerland. “We were saying that it’s not with tests that people would be saved. I understood our mistake when I saw that in Germany, their mortality total was much less than in France, whereas they are right beside the [hard-hit north-east French region of] Grand-Est.”

“In reality, by testing more,” he added, “people more naturally adopt physical distancing, as a result helping to shut down chains of transmission.”

The virus began spreading in north-east France notably following a five-day gathering of around 2,000 people for Evangelical Lent celebrations in the town of Mulhouse, in Alsace, between February 17th and 24th. On March 1st, the first cluster in Alsace was reported by Geneviève Chêne, when several cases within one family were discovered. “We learnt on March 1st that the family, who were sent [for treatment] to Strasbourg, had taken part in the evangelical rally,” recalled Marc Noizet, head of the A&E unit at the main hospital in Mulhouse. “We told ourselves then that things were going to be complicated.”

But the epidemic arrived quicker than expected. “Between February 24th and March 1st, we saw the number of calls to the emergency services double,” said Noizet. “On March 3rd, we opened up our first 14 beds dedicated to people suffering from Covid-19. They were immediately taken up. That day, calls to the emergency services tripled in comparison to usual activity.”

On March 2nd, a crisis management unit was created in Mulhouse to deal with the situation, and on March 7th a “white plan” was declared, which is a measure allowing the postponement of all non-urgent hospital care. “That day we saw the arrival of our first patients in a serious condition, who had to be taken into intensive care,” added Noizet. As of March 13th, “it was a tidal wave”, he said. “We were never in a position of anticipating. Every day we had to face new problems.”

Noizet said that the national health authorities did not take measure of what was happening. “Around March 10th, we heard Jérôme Salomon advising that all people with symptoms should be tested at hospitals. But we already no longer had sufficient [equipment for] tests. There were ill people everywhere in the streets. Our [local] prefect, our ARS, nevertheless tried to send on the information [to the national health authorities]. On my side, I spoke with the media. Our [hospital] director was contacted quite late by the inner cabinet of the minister of health.”

Realising that his colleagues in other parts of France did not understand the crisis in Alsace, after he received calls from them during week of March 9th asking what was happening, Noizet sent out a general email “to tell them to prepare themselves”.

The director-general of the ARS regional health agency for the greater Paris region, Aurélien Rousseau, said he had seen “as of January 24th that the situation was going to be quite complicated”. That was when the first two Covid-19 patients – “two Chinese tourists, who had taken river boats [on the Seine], who went to the big department stores” – were admitted to hospital. Rousseau said that he realised that the number of cases would overwhelm the capacity of leading epidemiological investigations to trace and isolate those who were ill. “As of March 5th-6th, we had the first clusters,” he recalled. “As of March 10th, we were seeing an exponential growth, 92 cases on March 11th, 376 on the 14th. On March 15th, our teams were drowning. But we continued to trace cases to gain time on the epidemic, to give us a few extra days of preparation in the hospitals.”

Infectiology professor Éric Caumes of the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris said that at the time he felt reassured by the fact that the virus had not spread widely across south-east Asia. But then he read an article in the Journal of Travel Medicine published on March 13th which detailed the comparatively vast resources that the authorities in Singapore had made available to deal with the virus. These included testing of 2,200 people per day, the placing in quarantine of 40,000 people who had had contact with those identified as positive for Covid-19, the use of masks, and temperature tests on people in companies and at borders. “I had not been aware that they mastered things to that level,” Caumes now says. “They had the industrial capacity to multiply tests. In comparison to them, we are developing countries.”

Speaking alongside health minister Olivier Véran on March 11th during a studio discussion programme on the LCI television news channel, Caumes warned: “We are certain that a scenario [of an epidemic] like that in Italy will occur, so we’re not really sure whether the authorities have taken the measure [of the situation].” Already, hospitals in northern Italy were witnessing chaotic scenes. The health minister, speaking on the same programme, attempted to be reassuring. “We are putting everything in place to cope with an epidemic,” he said. “If the epidemic is less strong than forecast, all the better. If the epidemic is severe, we will have done the lot to prepare the health system.”

Caumes said that that evening he had the impression “of being taken for a fool”. He recalled: “I ended up believing them, because they never stopped saying that we were ready. I still had a certain confidence in the system’s capacity to ride the shock.” The next day he lunched with a clleague from the hospital, a parasitology professor, Renaud Piarroux. “It was the first time that I spoke with someone who was more pessimistic than me,” recounted Caumes. “And he convinced me that even the [Paris hospital administration] AP-HP was not up to speed, that nothing was ready. Neither respiratory machines, nor beds, nor masks, nor tests. We were ready for nothing.”

The same day, the two men went to speak to their hospital’s director and then with the head of the AP-HP, Martin Hirsch. “We convinced them,” said Caumes.

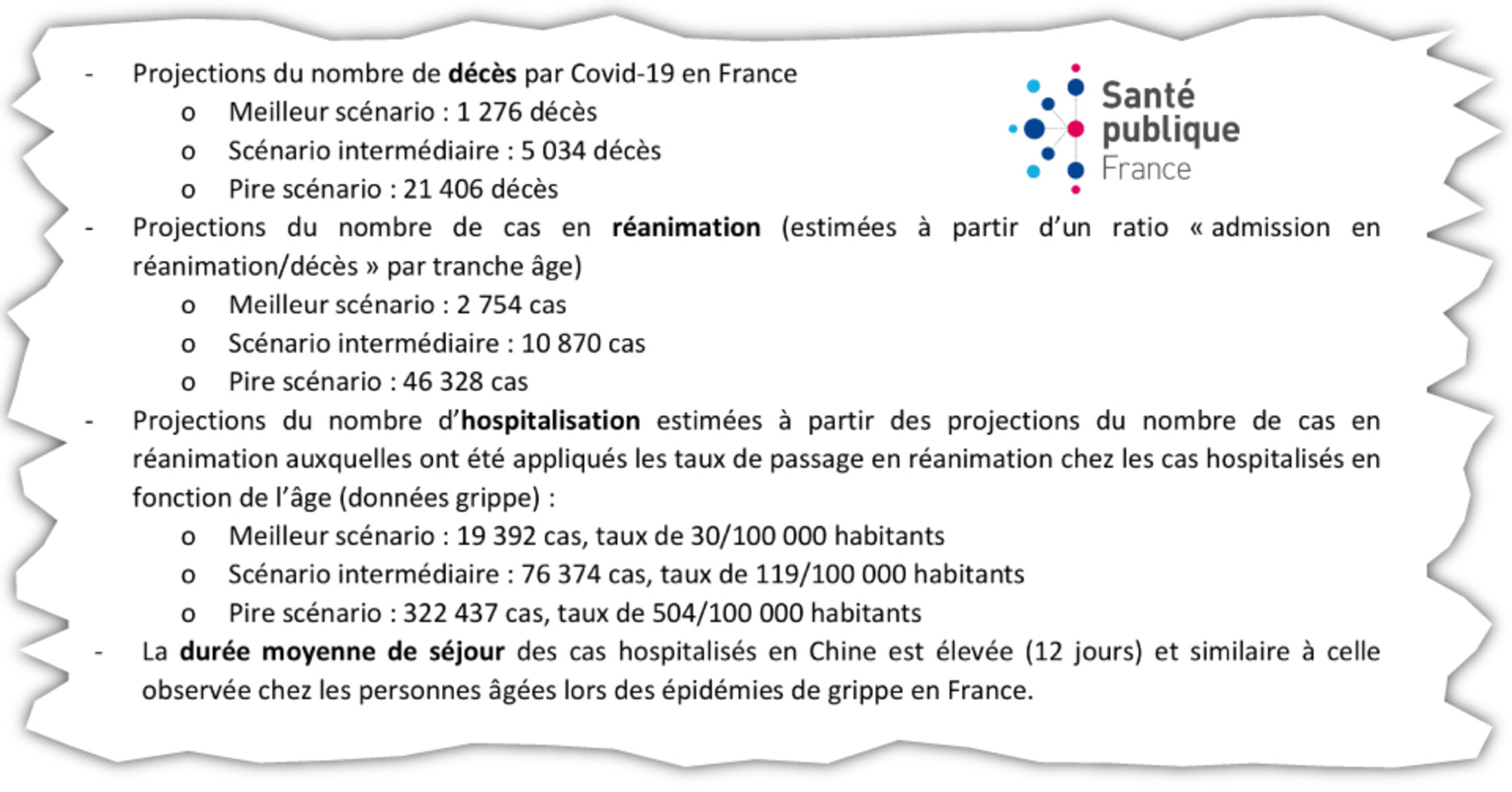

That week was the last before the introduction of what would be a two-month national lockdown on public movement. It was also when Santé publique France produced its first modelling of the potential future national mortality toll of the epidemic. Its worst-case scenario was a total number 21,406 deaths which, while it would prove to be a considerable under-estimation (the total numbers of deaths passed to 30,004 on July 11th), gave a clear warning of the extent of pressure that the hospital system in France was about to face. Its best-case scenario was 1, 276 deaths, and its intermediary projection was 5,034 deaths.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“There was a [worst-case] catastrophe scenario with a need at a national level for 46,000 intensive care beds,” recalled Aurélien Rousseau of the Île-de-France (greater Paris) regional health agency. “We thought our limit in Île-de-France was 2,000 beds.” Finally, the medical staff in Paris and its surrounding area managed to increase that capacity to a total of 3,000 beds.

“The problem is less about stocks, which by definition reach expiry dates, than our reactivity,” said Philippe Sansonnetti, a micro biologist and epidemiologist with the Pasteur Institute. He says that the threat of pandemics should become a constant preoccupation, as in China and South-East Asia. “As Albert Camus wrote in The Plague, ‘one only thinks of catastrophies when they fall upon you’,” he said. On a more upbeat note, he said he believed that, “We’re coming out of the crisis better than when we entered it”.

The lockdown apparently played a more effective role against the spread of the virus than expected. “Since May 11th, there are fewer cases than expected,” said Aurélien Rousseau of the situation in Paris and its surrounds. “But that could be because we’re not recognising cases. I would favour that hypothesis.” His regional health agency has organised major testing programmes, with testing available without doctor’s prescriptions and the sending out of 1.4 million vouchers for people to test for free.

Since May 11th, there have been 114 clusters discovered in the Paris Île-de-France region, of which 27 are active. A quarter of all of them were identified in health establishments, and half in collective sites like workers’ hostels and social emergency shelters.

Rousseau said his agency was closely monitoring “several indicators” which include the trend in the number of calls to the emergency medical services, the percentage of tests that are positive to Covid-19, and A&E admissions. He describes the current situation as being “under control”, but he warns that while the indicators of infections are low, they have now stopped falling. “When one sees what’s happening abroad, our vigilance is at a maximum,” he said.

Now, as in March, the views expressed by the medical profession are cacophonic. Éric Caumes warns of a second wave of the epidemic that could strike “as of this summer”, notably because of people returning from holidays abroad without being tested and what he calls a “laxism” in France. Meanwhile, his colleague, Yonathan Freund, head of A&E at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, is irritated by the alarmists. “What do we want, that the virus no longer circulates? In that case we must stay in lockdown,” he said. “But then, when does one come back out? We all have the indicators now, we can monitor the virus so that it doesn’t rise above our capacity for hospitalizations. We’ll see.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse