In the summer of 1885, and using a preparation of his own invention, French scientist Louis Pasteur began treating several children bitten by dogs that were suspected of having rabies. At that time rabies was a rare disease which provoked fear both because of its awful symptoms and the near-certainty that it would lead to death.

Historians of science have shown in their research how much was at stake for Pasteur at the time. Even his closest colleagues doubted that the scientist's preparation of rabbit spinal cord infected with rabies could be applied to humans. But in the lottery that medical experiments sometimes resemble, Pasteur won big. Thanks to his treatment, several of the children escaped the dreadful agony that had awaited them.

From across Europe, patients bitten by dogs suspected of carrying rabies then descended on the small Parisian laboratory in Rue d'Ulm where Pasteur worked. Three years later, in 1888, a private institute bearing the scientist's name opened in Paris, with its primary mission being to dispense rabies vaccine. Forty years later the planet had a total of 17 Pasteur Institutes, whose main mission was also to supply vaccination against rabies. Their number continued to grow, helping to spread France's influence through the name of one of the country's most prestigious scientists.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

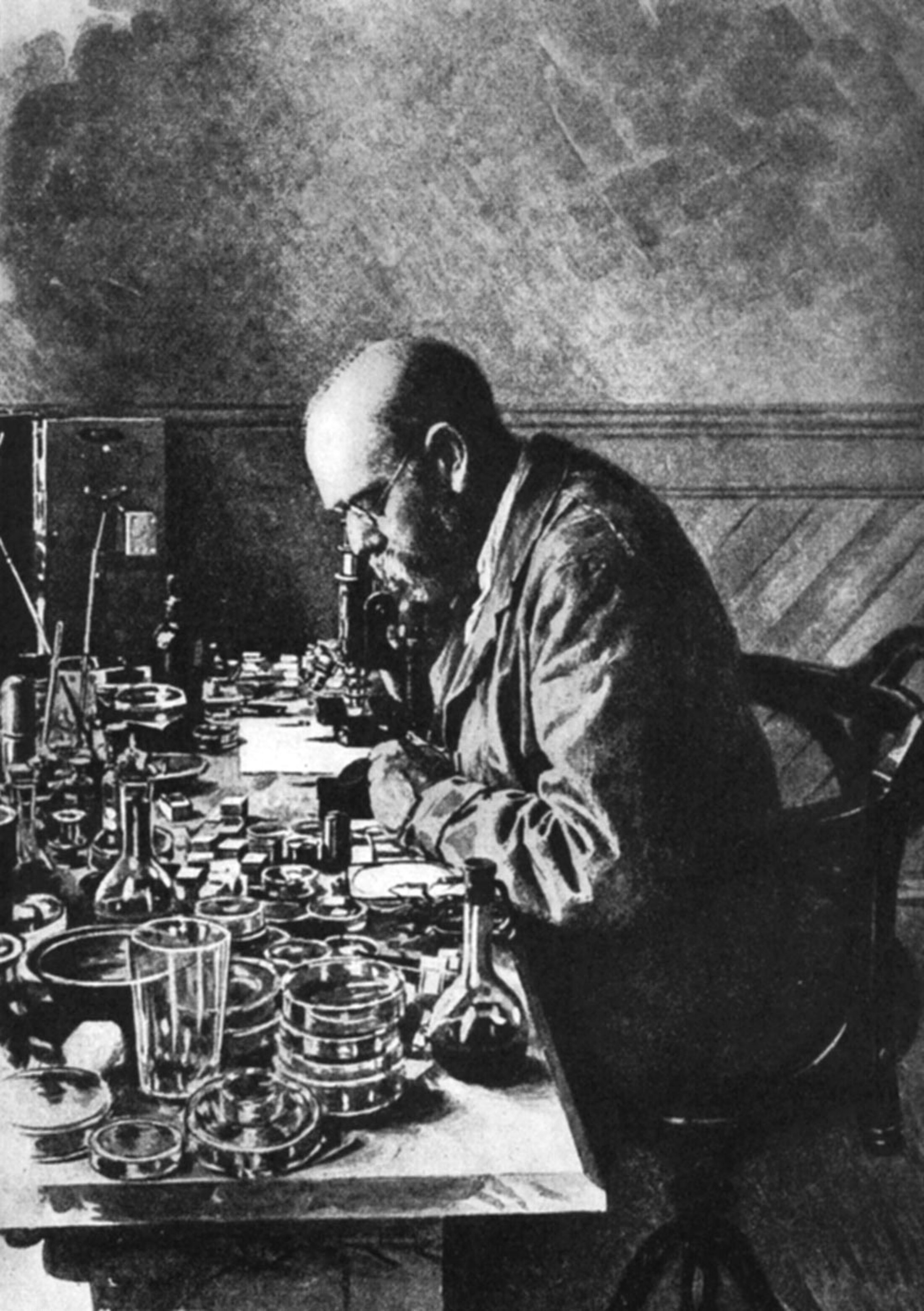

Microbiology had been growing fast at the time that Pasteur made his breakthrough. This fledgling branch of science was looking at the micro-organisms that scientists had been observing under microscopes for two centuries but which they had only recently successfully isolated, named and cultivated. The greater understanding of these microbes led both to good outcomes – the fermentation process that would play a key role in preserving food for example – and bad ones, in the form of the illnesses they sometimes caused.

The discovery of the world of microbes was one of the main breakthroughs of the late 19th century, a period marked by a confidence in the progress of science that bordered on faith. Two key figures emerged from it: the French chemist Louis Pasteur and the German rural doctor Robert Koch. The two scientists met only once, at a conference in London in 1881, and were aware that they were in competition with each other.

The former demonstrated on numerous sick animals than an injection of microbes that had been 'attenuated' or weakened protected against disease. The latter won fame for identifying pathogenic microbes, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes tuberculosis and which is sometimes still referred to as 'Koch's bacillus'.

In geopolitical terms, Pasteur's crucial breakthrough came fifteen years after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, at a time when the French Republic and the German Reich were rivals across all domains. The latter had developed a clear advantage because it had managed to transform its medieval universities into modern research centres. Louis Pasteur, meanwhile, was a fervent nationalist, a conservative who had been close to the deposed emperor Napoleon III, and he was well aware that his scientific rivalry with Robert Koch, who was 21 years his junior, also had a political dimension.

In 1884 a cholera epidemic had ravaged Egypt, exacerbated by growing globalisation linked to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The weak government in Egypt, under the influence of European colonial powers, asked for help.

Too old to go himself, Louis Pasteur arranged for members of his team to help on behalf of France.

Robert Koch, meanwhile, went to Egypt in person, tasked by the authorities in Berlin. The German mission became the first to identify the bacteria responsible for the disease. The health impact of this discovery was in fact modest, as the inactivated vaccines created from the bacteria were found to be pretty ineffective against cholera. But the political impact of the discovery was striking.

As for the French, they were hit by the death of one of their mission's main members, Louis Thullier, a victim of cholera at the age of 26.

At that very same time an international conference, held in Berlin from 1884 to 1885 and organised by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, was presiding over the carve-up of Africa between the European colonial powers. And Germany had now gained an advantage over its arch rival France by showing itself to be at the cutting edge of the new technology, one which held out the promise to worried colonists of them being able to survive in a tropical world that was supposedly infested with noxious air.

There is no evidence to show whether it was a sense of nationalistic revenge that then led Louis Pasteur – who was not a medical doctor – to start experimenting on humans. But the fact is that he took this step in July 1885, just one year after the French mission's setback in Egypt.

A great deal of flattering literature was devoted to the case of Joseph Meister, a nine-year-old boy originally from Alsace, which coincidentally had been annexed by Germany from France in 1871. Bitten by a dog that was thought to have had rabies, the boy's life was saved by Pasteur after the scientist had him injected with rabbit spinal cord tissue containing the disease.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Close examination of his laboratory notebooks show that other children who had been treated in the past by Pasteur's method were not so fortunate and had gone on to die from rabies. But at the time medical experiments were not encumbered by ethical committees. No doctor today would start experiments as dangerous as those that Pasteur carried out on those children. As he said himself: “...chance favours only the prepared mind.”

Gradually refining his methods, and using his therapeutic vaccinations (the rabies virus, whose existence was not known at the time because it could not be isolated, has such a long incubation period that a vaccination can have an impact even after contamination), Pasteur managed to save several patients bitten by rabid dogs.

For both Pasteur and France's Third Republic it was a triumph. For the first time, microbiology had succeeded not just in understanding the origins of diseases and preventing them by hygiene measures, but had also managed to cure them. Rabies vaccination was the main achievement of the new science pioneered by Pasteur. This breakthrough went on to spread to the whole of the world, profiting from the fact that rabies is a rare illness but one which is present just about everywhere on the planet.

Within two years of these crucial experiments in Paris, 14 centres around the world were carrying them out, from Odessa to New York, and including countries in Latin America. Despite the rivalry between Koch and Pasteur, Germany also followed suit.

The Pasteur Institute in Paris was officially opened on November 14th 1888 by the French president Sadi Carnot. It had been set up thanks to a public subscription to which the Tsar of Russia, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the emperor of Brazil all contributed. It was a private institute that was dedicated, as its founding statutes stipulated, to being a “dispensary for the treatment of rabies, a research centre for infectious diseases and a teaching centre”.

Other Pasteur Institutes quickly followed around the French empire, in Saigon (1891), Tunis (1893), Nha Trang on the coast of Vietnam(1895), Dakar (1896) and Antananarivo in Madagascar, all with the same main mission of providing the anti-rabies vaccination. But these offshoots were not limited to the growing French Empire. Other Pasteur Institutes were set up in Sydney (1888), Constantinople, now Istanbul (1893), Bangkok (1913), Brussels (1920) and other centres.

These institutes were for the most part run by scientists who had trained in Paris under Pasteur (who died in 1895). They were, in the words of the science historian Anne-Marie Moulin, the “apostles of Saint Pasteur”, spreading the new Pasteur law around the world like members of some monastic order.

In practice these institutes were very independent from the original institute in Paris, especially financially. The 'Pasteur Institute' label was a form of franchise, which was granted according to the wishes of Émile Roux, Pasteur's loyal chief assistant, who took over as head of the institute in Paris after the founder's death. The foreign institutes received virtually no subsidies from Paris and had to live from their own resources: through selling vaccines or from grants raised from local governments, including colonial ones.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

There is a striking contrast here with the institutes run in Germany by Pasteur's great rival, Robert Koch. These were all wholly funded by the German state. Research there was carried out in the public sector, though the production of vaccines and then therapeutic serums (which in France were carried out by the Pasteur Institute which got most of its income from this up until World War II) was overseen by private firms. These were often set up by former colleagues of Koch, such as Emil Adolf von Behring, who established the Behringwerke site at Marbourg which still exists today.

Up until his death in 1910 Robert Koch travelled the world spreading his views and advice on microbiology and its importance in fighting epidemics, but did not create any research centres overseas. It was from within German universities that the 'Tropeninstitut' – research centres into tropical diseases – developed.

As proof that they were not simply a tool of the French Empire, the network of Pasteur Institutes around the world to a great extent survived the decolonisation process of the post-war period. Today they are part of an international network of 32 establishments spread across five continents.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 the German Chancellor Bismarck had wanted to channel France's desire for vengeance over defeat at the hands of the Prussians in 1870 into colonial expansion in Africa. And while the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) is still at the centre of public health in Germany, the network of Pasteur Institutes has remained an instrument of 'soft power' for French diplomacy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter