Death often brings about consensus, sometimes to the point of forgetfulness. That is all the more so when the life of the person who has disappeared imposes itself upon their denigrators by its coherence and rectitude. That is the case with Robert Badinter, who even received the stereotyped homages – “an outstanding figure of the intellectual and legal sphere” who “all his life championed his ideals, with steadfastness and eloquence” – from the two principal figures of the French far-right – Marine Le Pen, who already sees herself becoming head of state in the presidential elections due in 2027, and Jordan Bardella, head of her party, the Rassemblement national (the former Front national).

The political family whose ideas Badinter had, throughout his life, fiercely fought against, showed no hesitation in paying public tribute to his memory. But instead of these homages – made with hypocritical decorum and as a political tactic –, it is rather by way of the intensity and the constancy of the many attacks against him from the far-right that one can measure the sound nature of the combat that animated Badinter’s life.

In October 1983, when I was a young journalist with French daily Le Monde – I was 31 – I found myself, together with a colleague, a rare outside witness to a meeting in a Paris conference centre of far-right groups. Entitled “Journée d’amitié française” (Day of French friendship), the regular refrain at the meeting (see more on my blog) was one of hatred, hatred of Jews above all and, in particular, hatred of Robert Badinter, then justice minister since the 1981 election of François Mitterrand as president.

Every militant French far-right group was represented, in communion around the Maurrassian credo of the “four superpowers [which] colonise France”, namely “the Marxist, the Masonic, the Jew, the Protestant”. Antisemitism was expressed without reserve and in the most hackneyed terms: “The Jews are at the two poles of contemporary society: founders of financial capital and the most vehement critics.”

Among those taking part was Marine Le Pen’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the Front national and who, beginning with the European Parliament elections the following year, would begin his electoral ascension and the de-marginalisation of his political family’s ideology. It would serve as a revenge over his double defeat, in 1944 – the liberation of France –, and in 1962, when Algeria won its independence from France.

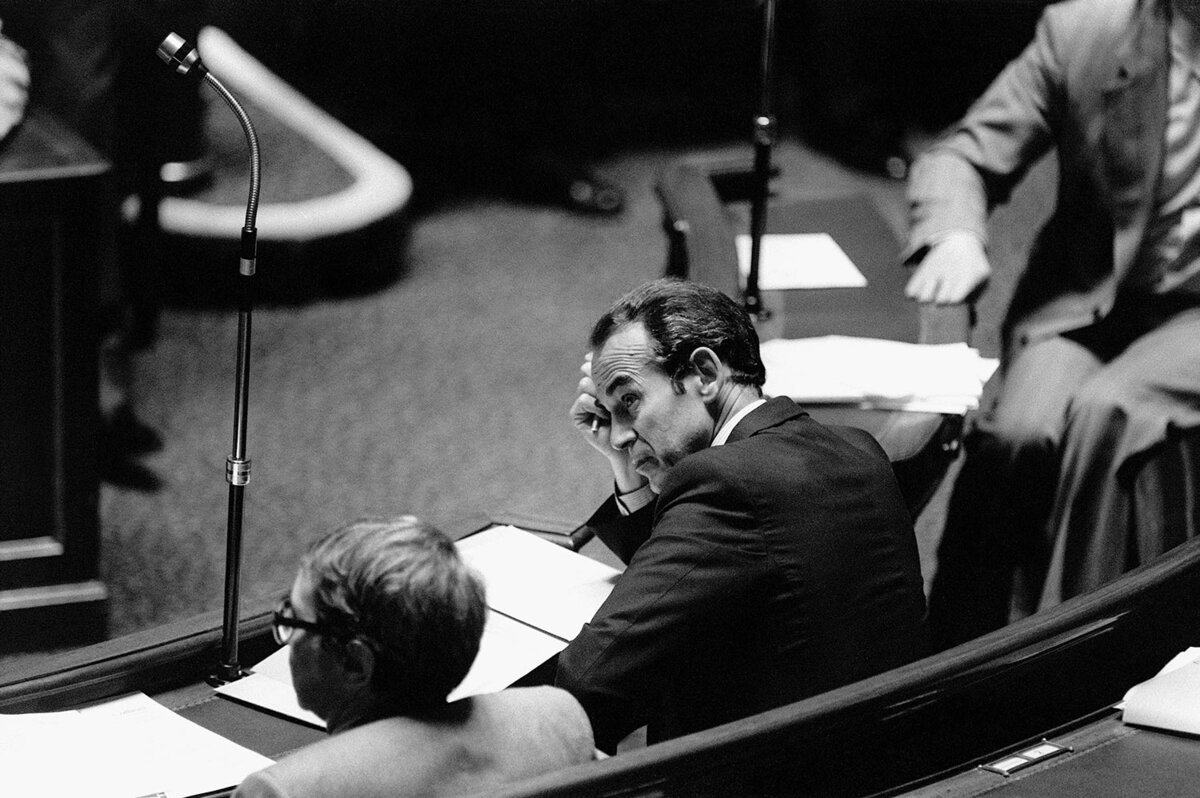

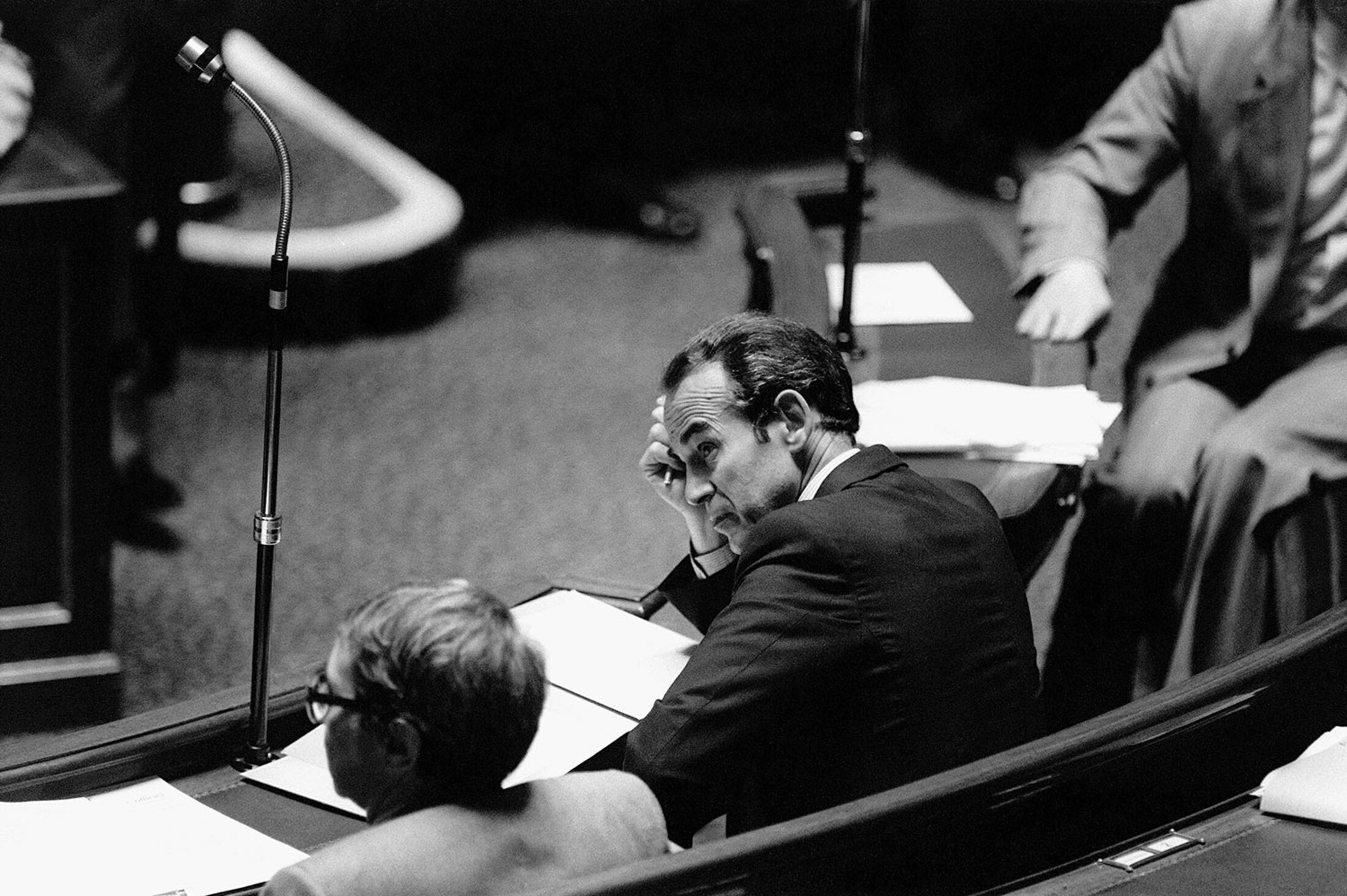

Enlargement : Illustration 1

A few months before that far-right meeting of October 1983, which was a day of hatred and not “friendship”, several thousand police officers marched unobstructed in a protest through Paris (video available here) which ended under the windows of the justice ministry. There, they demanded the resignation of Robert Badinter, calling him the “minister for delinquency”. Another slogan, “Badinter to the execution post”, could be heard in the seditious march organised by police staff unions and the far-right. The protest followed a funeral ceremony, in the courtyard of the Paris police prefecture, of two police officers murdered on the capital’s avenue Trudaine by the terrorist group Action Directe. Among the protestors present that June 3rd was Jean-Marie Le Pen, who visibly felt at home amid the procession.

Robert Badinter represented everything that the far-right fought against; radical democratic requirements of France’s republic, and the uncompromising defence of equal rights. Beyond the historic symbol of the abolition of capital punishment in France in 1981, which he led with panache, he represented a politically liberal conception of a constitutional state which protects its citizens from abuse by the powers that be, public administrations, the police and the justice system – contrary to the stunted vision that circulates today, that of the almost absolute right of an authoritarian and repressive state.

Badinter drove the abolition of certain courts of “exceptional” jurisdiction (such as armed forces’ courts sitting in peacetime), brought an end to the criminalisation of homosexuality, concerned himself with the conditions of the prison population, and rose against the excessive jailing of offenders. He attacked attempts to make political gain from criminal cases, argued the need for the social reinsertion of delinquents, urged greater deontological standards within the police, and fought against racism. All the judicial and political philosophy of his actions would see his enemies pass him off as a dangerous laxist and harmful purveyor for minorities.

Hatred of people always ends up resembling Russian dolls; from the anti-Semitic declarations of that meeting in October 1983, when Robert Badinter was made the special target, other forms of hatred were introduced, and which have since proliferated into open public expression. One of the speakers at that meeting, author of a pamphlet entitled Ce canaille de Dreyfus, declared that immigrants “breed like rabbits” to the point whereby a “Muslim president” lay in wait for France.

Staggered by what I heard that day, and which to me did not appear anecdotal but instead prophetic of the rot to come in our public life, I wanted to meet with Robert Badinter to talk to him about my concerns. I found myself before a man who had chosen to face this ignominy with nobleness and uprightness in equal measure, and as silent as firm.

Rather than giving them the gift of lowering himself into entering the arena, riposting and arguing, he preferred to follow his path at the service of the law, indissociable from the aesthetic of rectitude that inhabited the personage.

While they may be laudatory, the portraits of him published since his death underline his haughty character, his individualistic career, his status as a grand bourgeois, his reformist approach that had little in common with a revolutionary shake-up, and, of course, his passion for issues of justice ever since he entered the profession of lawyer.

Jewish and republican, republican and Jewish

But there is another dimension. To better understand what type of man Robert Badinter was, and what is his legacy, it is well worth delving back to French historian and sociologist Pierre Birnbaum’s 1992 book Les Fous de la République (published by Fayard). It is a story of emancipation at the heart of the French republic, thanks to it and, sometimes, despite it. It is the story of what Birnbaum calls the “Jews of State” who, under the 1870-1940 Third Republic, were able to lead a public existence as senior civil servants, in all the state’s administrations, while in their private lives remaining loyal to their Jewish traditions, without hiding them. Jews and republicans, republicans and Jews, both, and not one without the other.

In the same way, numerous other servants of the republic, when in its early years, were Protestants, demonstrating how much it is that minorities continuously reinvent its promise, unlike the conformism of the majority. Which is why conservativisms will always demonize them, in the manner of the Maurrassian theories cited above.

With that in mind, a homage posted on X (the former Twitter) by Emmanuel Macron was nonsensical: Robert Badinter, concluded the French president, represented “the French spirit”, as if France had a rooted identity, immobile and unique. Whereas its promise of emancipation has always advanced thanks to movements from afar and, notably, men and women from, or with origins from, elsewhere.

Born in Paris in 1928 to parents who had fled the pogroms in Bessarabia (which lay in modern-day Moldova), Robert Badinter was of the generation that survived the Shoah – unlike his father and other members of his family who were murdered in death camps – and who as a result was lucid about the fragility of the promise of the French republic (whose motto is “Liberty, Fraternity, Equality”). But also he was all the more convinced, with the same zeal of his predecessors, that that promise should be given life. A total zeal without concessions, to the point of rigidity, which in later life was illustrated in his intellectual reticence to evolve alongside the pressure of new demands – regionalist, feminist, anti-racist and internationalist.

For as much, it would be unjust to characterize him by his later, more conservative, positions. In 2011, before public debate in France had enduringly slipped into obsessional tensions over the subject of Islam, Robert Badinter, speaking on radio station France Inter, and with his trademark cold anger, deplored the treatment of Muslims in France, taking up their cause in the name of an authentic French republic, that of equality for all without distinction of a person’s origin, faith or appearance. It was remindful of his commitment, far too unrecognised, to the anti-colonial cause.

Examine this pair of scales: all the pleasures in the scale of the rich, all the miseries in the scale of the poor. The two parts, are they not unequal?

The real truth about Robert Badinter lies in the 1980s, when he displayed what he was capable of, and during which he became a statesman –presiding over the council of state, France’s highest administrative court, between 1986 and 1995, after which he was elected to the French senate (1995-2011). To look back on those years is to take measure of what we now miss with his disappearance. He was undoubtedly not beyond criticism, but he was assuredly a man of high standards, notably in comparison with what today is our public life and its media representation, in their dominant expressions.

Towards the end of his life, Robert Badinter was inspired to adapt a short and admirable 1834 novel by Victor Hugo, Claude Gueux, into an opera. Hugo, whose republican universalism was profoundly shared by Badinter, used the theme of the workings of the judicial system to illustrate social issues, inequalities and injustices. “Examine this pair of scales,” wrote Hugo at the end of the novel. “All the pleasures in the scale of the rich, all the miseries in the scale of the poor. Are not the two parts unequal?” Certainly, there is nothing revolutionary in that, but for the author, like for the lawyer, who both took on the stature of “righteous” in the pantheon of France’s republic, there is in that the expression of a scruple or a remorse.

Scruple and remorse. In contrast they would appear to be totally missing from current French presidential policies, which echo this extract from Claude Gueux: “Obstinacy without intelligence is folly soldered on to stupidity, and serving to prolong it. That goes a great way. Generally, when a private or public catastrophe has befallen us, if, after examining the ruins which strew the ground, we inquire how the building was put together, we find nearly always that it was blindly constructed by an inferior and stubborn man who had faith in, and who admired, himself. There are in the world a number of these head-strong fatalities who believe themselves to be providences.”*

I’ll leave readers to meditate on that warning, while thinking of the principal actors of our mediocre French political scene, they who now survive Robert Badinter, he who was of a very different calibre.

* An 1869 translation into English of 'Claude Gueux' by C.E. Wilbour for publishing house Carleton.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse