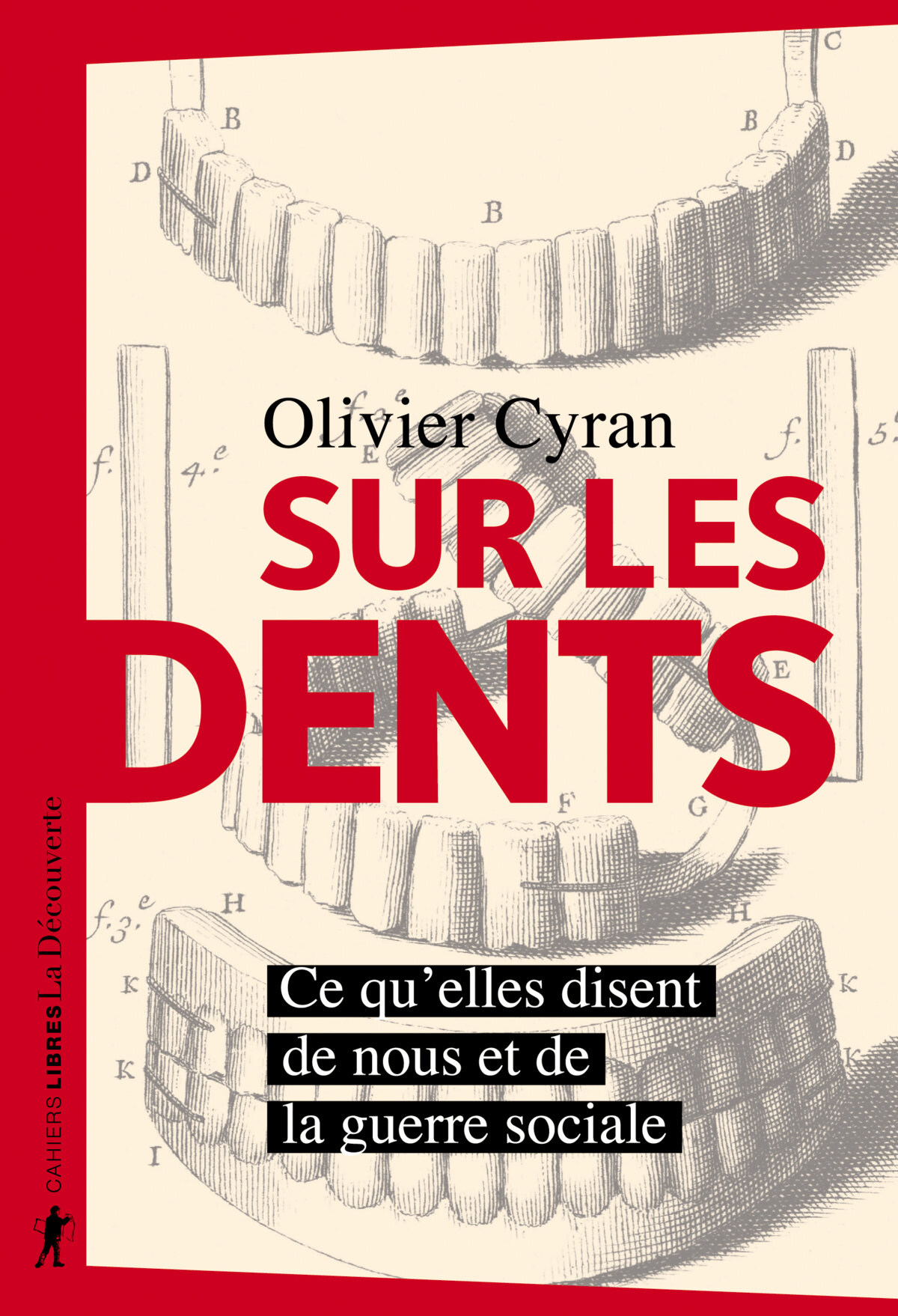

In his book Sur les dents – Ce qu’elles disent de nous et de la guerre sociale (roughly translatable as ‘What teeth tell us about ourselves and the social war’), French journalist Olivier Cyran examines the issues around the exclusion the worst-off in society from access to proper dental care, who often cannot afford even basic treatment, and whose lives are blighted by their situation.

Cyran, who admits to “stomatophobia – a fear of the dentist – writes in a lively and engaging style, dissecting a dental care system that is unequal and in which some professionals are only drilling for gold. Along the way he presents some chaotic dental experiences with all the suffering that failed interventions, and trickery, can lead to. But above all, it probes the subject of teeth and dental care as a study of society, a metaphor where the class struggle is still played out, and to which racial, social and conjugal violence is joined. “It’s an organ that materialises the balances of power that exist in society,” says Cyran.

Indeed, in France, the independent ‘observatory of inequalities’ estimated in a 2019 study that almost a quarter of children of blue-collar workers have untreated dental caries, compared with less than 4% of the children of senior management professionals. Indeed, teeth are often regarded as reflecting someone’s social situation, as illustrated by the controversy surrounding former French socialist president François Hollande when he was alleged to describe the poorest in society as “the toothless”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Beyond the clichés, however, Cyran offers a panoramic, humane and informed view of the subject. The roots of his project grew from his experiences as a reporter when interviewing people from working-class environments and became aware of the troubled relationship they often had with their teeth.

“I am interested in them as an extremely strong and painful indicator of a social status in which the intimate, the social, the political and the domestic are mixed, and for me it was worth unravelling these threads and extricating their driving forces,” Cyran told Mediapart.

While a French health ministry study estimated that 45% of manual workers declared that they had at least one tooth missing, compared with 29% of those in managerial jobs, dentists and official dental health campaigns claim that maintaining a healthy set of teeth is easy. “There are perhaps people who have a less healthy base, more to do with gums than teeth in fact, but as of the moment that from early childhood you have good buccal-dental hygiene and a balanced diet, there’s no problem,” commented one dentist, cited in the book, who carries out voluntary work for a mobile dental care centre. But as Cyran points out, “in the world we live in, the possibility of leading such a virtuous and protected life is not equally shared”.

It was during his reporting years ago that Cyran met Bader, who is quoted at length in the book about the consequences of having a toothless mouth. Bader is today aged 53, and it was when he was 23 that his teeth began loosening, after visiting a dentist to have them scaled. He developed gum disease, periodontitis, and discovered that the tartar, the calcified deposit removed by the dentist, had been holding his teeth in place. This led to all his teeth being removed and replaced with dentures. He recounts the traumatism in Cyran’s book: “You are not given preparation for anything. There was no warning, no psychological support. I had to deal with the shock on my own. It was very violent. It took me eight years before being able to kiss my daughter. I lived with dentures like it was an absolute disgrace.”

Bader says he still today has great difficulty living with this foreign body in his mouth. “When you feel diminished, you can’t help feeling shame. That’s how it is. You can domesticate your shame a bit, but it never leaves you, it’s your companion for life,” he told Cyran.

Cyran cites another case, that of Nordy, who lost her teeth after she was repeatedly beaten by the father of her children, which she said involved punches, head-butting “and even the barrel of a shotgun”. She had to reconstruct her life, in every manner. Cyran writes: “The rebuilt teeth of Nordy don’t only tell of a long series of hurt and brutality, they also concretise the process of physical, psychological and political reconstruction that she imposed on herself to become the fighter that she is today. These are teeth on which you can count, as ready for biting as they are for laughing.”

Nordy told Cyran how, when a schoolgirl, she left her rural surrounds in the Auvergne region of central France to complete her final years of secondary education in the lycée of a town. “What’s funny is that the social group of each person was evident from their mouths,” she said. “Those from the town had impeccable teeth, while those from the country recognised each other by their damaged stumps or the holes left by those which had fallen out. You had those who gave a full-teeth smile and you had the others who didn’t smile, or did with care, head bowed and masking their teeth with a hand.”

Later, as an adult, after years of suffering and the impossibility of smiling, Nordy managed to separate from her violent her partner and attempted to get her life back on track. “I managed to put a bit of money aside and have my teeth reconstructed, with implants, one by one,” she told Cyran. “It costs a crazy amount of dosh, but I’m getting there by staggering payment over five years. For that, I first had to obtain the lifting of my bank account ban and hunt down a dentist who accepts to be paid in instalments.”

The dentists who illegally refuse to treat the poorest

Suffering and pain run through Olivier Cyran’s book, as do also the financial barriers to dental health. The worst-off are unable to pay the exorbitant cost of some dental operations. With the help of a “Marxist” dentist, who he gives the name Paul Lafargue, the author analyses the behind-the-scenes world of a profession in which some are driven solely by the lure of money-making.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The social security system’s criteria for partial refunding of treatment establishes a sort of heirarchy between the different forms of dental care, making routine maintenance less lucrative for dentists than, for example, carrying out implants. Which encourages some to place a priority on the latter.

The dentist behind the pseudonym of Paul Lafargue says that the imbalance is exasperated by increased demand. “This overload prevents us from taking the time needed to properly treat each patient,” he tells Cyran. “If you come to see me for a buccal-dental check-up the fee is 23 euros, meaning peanuts. So, either I’ll skip through the thing in a quarter of an hour, or I decide to do my work seriously and I’ll spend three-quarters of an hour. If I do that several times during the day, I’ll soon find myself stony broke.”

The French government put in place a reform, in January 2020, which entitles some to free dental care. Mutual insurance companies, for example, must now provide the full top up for the implants of the most basic protheses – such as those in metal for the back teeth. For Cyran, it is still too complicated, notably because of the Covid-19 epidemic, to evaluate the efficacy of the reform, which he argues is “above all a possibility given to the [insurance] mutuals to increase their already high prices, with the risk for the worst-off of losing their mutual [insurance contract] if they can no longer pay for it. The dentist will always be encouraged to propose non-refunded treatment”.

In 2009, the then French health minister, Roselyne Bachelot, introduced a measure allowing the establishment of “low-cost” dentistry centres to open up in France in order to democratise dental treatment, for better or worse. It led to the creation of chains of private dental centres with same-sounding names like Dentego, Dentimad, Dentifree, Dentalvie, Dentymed, Dentasmile and Dentaxia.

The latter went bankrupt in 2016 after causing damage to the teeth and gums of an estimated 3,000 patients who had paid the fees for their treatment in advance. “Hundreds of patients came away not only mutilated, infected or toothless, but also financially ruined because the ‘care’, payable in advance, had already been paid for, often following a loan that they obviously had to continue to pay off,” writes Cyran. “In fact, in general, the loan had been taken out under the amicable pressure of Dentexia’s sales staff, who pulled out their magic [loan application] forms as soon as they saw you go pale at the amount on the estimate.”

Cyran details at length the story of Dentexia and interviews victims of the disaster, and who are still waiting for their cases to come to court. The judicial probe is ongoing, and some individuals have been formally placed under investigation (one step short of charges being brought). One of those seeking reparation for the company’s mistreatment is Abdel Aouacheria, who developed an inflammation of the pulp of his teeth, the pain of which is difficult to treat. He established a victims’ collective group to fight their claims over the Dentexia fiasco. “This army of handicapped mouths spiked with wires, bits of metal and defective apparatuses threw themselves into action against the public authorities to force them to no longer ignore their torture and to fund dental reconstruction work which they urgently needed,” writes Cyran. “It took them two years of dogged mobilisation to win their case.” If Abdel Aouacheria and his collective finally found relief from their “torture”, others are still waiting for justice while crippled with pain.

There are many cases of dentists who refuse to repair the damage caused by others in their profession. “Dentists are not held responsible with regard to their badly performed actions and gestures,” says Cyran. “They are not obliged to repair their mistakes, they are exempted from any requirement, unlike doctors.”

He also recounts how some dentists illegally refuse to treat the very poorest. “It has become normalised to refuse to care for those who are beneficiaries of the CMU [a universal medical care fund for lowest income earners, now renamed PUMa] or the AME [state medical aid available to foreign nationals without legal residence status]. Some even notify this on websites for booking medical appointments, whereas the practice is illegal.”

Cyran concludes that to overcome the problems there should be a public dental service, along the lines of the public hospital system, or alternatively the establishment of dental care centres which have a social vocation, “freed from the necessity of margins and making profit”.

-------------------------

Olivier Cyran’s book Sur les dents – Ce qu’elles disent de nous et de la guerre sociale, is published by La Découverte, priced 20 euros (14.99 euros in e-book format).

- The French version of this article, lightly abridged in this English version, can be found here.