Benoît Puga. The name reverberates like an overstretched rubber band. Or, if one prefers to use a military metaphor, like the muffled sound of a submachine gun. Behind his impeccable demeanour and faintly ironic smile, Benoît Puga is one of the most powerful men in the French Republic but also one of the most secret. A general with five stars notched on his képi, the highest rank in the French army, his title is Chef d’État-Major particulier du Président (CEMP), or chief of the president's military staff. In other words he is the French head of state's military advisor and his principal consultant on all defence issues.

But in one important respect General Puga is different from all his predecessors in this key post in France's Fifth Republic: having been a surprise nomination under Nicolas Sarkozy in March 2010, he is still in position today, more than two years into François Hollande's term of office. This ability to survive the transition from one political persuasion to another – Right to Left - is unique, and says a great deal about the man himself. But it also speaks volumes about the way that President Hollande manages power at the Elysée. In addition, his longevity in the post and the way in which the general makes use of his influence is starting to irritate a large number of socialists.

As the military know and often point out, in a country such as France there is never really “peacetime”. Between its participation in United Nations peacekeeping operations, maintaining France's nuclear deterrent and conventional capability and various foreign interventions – which can vary from dealing with piracy to hostage situations - the government can never ignore the military agenda. This is especially true when, since 2011, France has actually gone to war on three occasions: in Libya, Mali and the Central African Republic.

If there is one thing that no one disputes about the current presidential military advisor it is his formidable military qualities. “He's a very good soldier who knows operations very well. He's a great professional,” says retired general Vincent Desportes. One of his predecessors in the post of presidential advisor, General Henri Bentégeat, notes: “He has formidable operational knowledge and when he's really in charge of an operation, it all goes well.” And the man who used to be Puga's superior officer adds: “He has a power I have rarely encountered: that of being able to reassure his bosses. When you have a man like that at your side, whether you're Nicolas Sarkozy or François Hollande, it's a great comfort.”

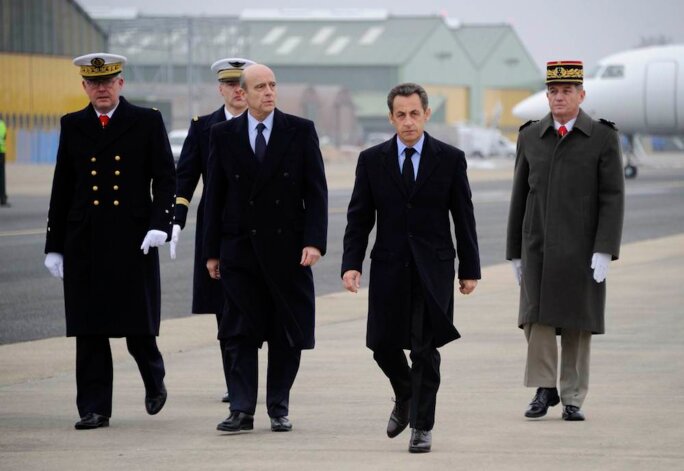

Enlargement : Illustration 1

After graduating from the elite French military academy Saint-Cyr in 1975, Benoît Puga spent time as a tank troop commander before quickly joining the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (known as 2e REP) of the French Foreign Legion. There he took part in the famous 1978 airborne operation at Kolwezi in Zaire – now the Democratic Republic of the Congo - to free local and European hostages held by the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo. It was one of his most famous armed exploits, and one which is cited in all biographies of him, even if for some of his detractors in the army the incident “is starting to get a bit dated”. Puga was subsequently involved in the majority of overseas interventions carried out by the French army at the end of the 1970s and the start of the 1980s; in the Gabon, Djibouti, the Lebanon, the Central African Republic and Chad.

Afterwards Puga's career as a senior officer took off, reaching the rank of general in 2002, as he alternated between positions of command in France and abroad. In particular he was military advisor in the former Yugoslavia to Carl Bildt, the European negotiator for the Dayton peace agreement who became the United Nations' special envoy for the Balkans. Between these positions, in 1996, he commanded the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment, leading them during two French operations, in the Central African Republic and in the Congo.

In 2004, at the age of 41, Puga began the next and final stage of his career which would see him become Commandement des opérations spéciales - in charge of France's special operations - and then officer in command of military operations at the army general staff. Finally, in 2008, he was appointed head of military intelligence. His career was marked by two main themes – Africa, and “operational” command. This means that today he knows personally a number of French-speaking African leaders and their military staff, chief among them the long-serving president of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, and the Chad president Idriss Déby.

Many of his military colleagues consider Puga to be something of an old-fashioned “colonial officer”; a man of action, operating out in the field. One of his former underlings, who is no great fan of Puga and who asked not to be named, believes moreover that the general’s subsequent elevation to the post of presidential military advisor is an “anomaly”. He says: “Puga is above all a guy who runs operations. He should never have been reached this position which is made for senior officers who have had a more 'political' career, in the sense that they have taken on responsibilities involving greater reflection, management or giving advice to civilians.”

So how, then, did Puga reach this position of presidential military advisor? And how has he been able to hold onto it despite a background markedly of the Right, and despite the growing unease that he causes among socialists who take an interest in defence issues and who mistrust him? In essence it is for two reasons: his image and his network of contacts.

'He used his position as director of military intelligence as a springboard to enter Sarkozy's world

The most noteworthy aspect of General Puga's personal background is his membership of the Catholic fundamentalist movement, something which he has never hidden. He is the son of Colonel Hubert Puga who joined the so-called Algiers putsch, a failed attempt to overthrow President Charles de Gaulle in April 1961. Colonel Puga was jailed for five years for his role in the plot and thrown out of the French army. He died in 2010. One of Benoît Puga's brothers, Denis, is a priest at Saint-Nicolas du Chardonnet in Paris, a church which is affiliated to the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Pius X. Usually known in English simply as the Society of St. Pius X, this organisation describes itself as “traditionalist” but is commonly referred to as “fundamentalist”, and rejects the teachings of the Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s. Nearly all of Benoît Puga's children – he has eleven – have attended private schools linked to the Society of St. Pius X, in particular Saint-Bernard school at Courbevoie, a wealthy area on the outskirts of central Paris. Their christenings and marriages have been held at Saint-Nicolas du Chardonnet church.

A close friend of the Puga family is another military figure, General Bruno Dary, who ended his career in 2012 as military governor of Paris. Once he had left uniform Dary supported activists for the Le Manif Pour Tous collective of groups opposed to same-sex marriage and homosexual parenting. It was, meanwhile, no accident that when in June 2013 an extreme right-wing group called Lys noir ('Black Lily') called for a coup d'état to overthrow the current government, they put forward the names of three soldiers to lead the country: Generals Puga and Dary plus General Pierre de Villiers, the current chief of the defence staff for the French armed forces.

Even if these officers had absolutely nothing to do with this appeal, which they denounced without equivocation, and though their republication convictions have never been questioned, their names did not appear at the top of this junta by chance.

“Today a large section of French military leaders belong to the fundamentalist Catholic movement,” says Puga's former assistant, who thinks that as an atheist and divorcé he suffered as a result of this. “As the military lost a lot of its prestige as an institution after the Second World War, recruitment to Saint-Cyr has become extremely limited and has come disproportionately from very traditionalist families.”

A reserve officer who is an expert on defence issues plays down this line, though he also confirms certain aspects of the claims. “Those with a fundamentalist Catholic profile are a very small minority, not more than 10% and they're not looked on kindly in the army, contrary to what people think, because they're the type of people who annoy everyone and give the institution a bad image,” he says. “But it's true that they are over-represented at the top because they know all the tricks, in particular because they come from military families.”

Everyone who has worked with Benoît Puga agrees that he is a great networker. “A good officer always promotes alongside him soldiers who have served at his side, it's a military tradition,” says the defence expert. “But the problem with Puga is that he operates in a clannish way – he promotes those loyal to him, whatever their abilities, and removes those who don't agree with him or who stand in his way.” Among the first group is retired general Bruno Dary, the current chief of the general staff of the French army, Bertrand Ract-Madoux, and the Beth brothers. Emmanuel Beth, a former general in charge of paratroopers, was French ambassador to Burkina Faso until 2013, and Frédéric Beth, who is also a general, used to be in charge of French special forces and is now number two at the French external intelligence agency the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE).

Among those who are not part of Puga's 'clan' are a number of junior officers who “because at some time or other they've opened their mouth now find themselves shunned”, in the words of more than one soldier who has served with him. But those not in favour with the general also include several major figures in the military firmament such as General Didier Castres. He was the commander of Operation Serval in Mali and enjoys the support of the ministry of defence, but according to one advisor at the Elysée “Puga is looking to marginalise him”. And then there is the story of General Pierre de Villiers.

To tell this story, which says a great deal about Puga and the way he operates, one has to go back four years to 2010. At the time the Chef d’État-Major particulier du Président or CEMP was Admiral Édouard Guillaud, who had been chosen by President Jacques Chirac and kept on by President Nicolas Sarkozy. Guillaud had just been promoted to the top military post, Chef d'État-Major des Armées or Chief of the Defence Staff, and so there was now a vacancy for his old job. As with each occasion on which the post of presidential advisor came up, there were a number of candidates – usually there are at least two, never more than four or five.

One of the candidates at the time was Benoît Puga who was in charge of military intelligence. But the favourite was Pierre de Villiers, brother of right-wing politician Philippe de Villiers, whom the majority of military and civilian staff at the ministry of defence hold in high esteem. He is the youngest peacetime five-star general in the French army and has extensive experience, from Kosovo to Afghanistan, and from working with the prime minister's office and handling financial issues at the ministry of defence. He was both the perfect candidate and the one being pushed by the military general staff.

President Sarkozy received him at the Elysée and confirmed his appointment to the position. As he left the soldier, the president told him: “See you Monday!” De Villiers duly arranged his leaving party from his current position and told his peers of his new appointment. But several days later the news dropped: in the end the presidential military advisor was to be Puga, not de Villiers. According to several sources at the Elysée and the National Assembly, it was Claude Guéant, Sarkozy's right-hand man who was then secretary-general of the Elysée, and Bernard Squarcini, head of the domestic intelligence agency the Direction Centrale du Renseignement Intérieur (DCRI), who persuaded the president to change his mind. On a trip abroad the two men had apparently said of Puga: “He's a very good guy who renders lots of services as head of military intelligence.”

One Mediapart source says of the abrupt turnaround: “This kind of thing never happens! In terms of military culture, what happened was huge. Being the head of military intelligence should have been Puga's last post before his retirement.” Another source says: “[Puga] used his position as director of military intelligence as a springboard to enter Sarkozy's world. He drew on civilian networks and, which was the most unhealthy part, on the very heart of the Sarkozy machine, to remove de Villiers and get himself nominated! It was Salieri taking the place of Mozart...”

'Puga is one of two guys to get rid of... '

Once he was in position Puga became close to Sarkozy and, in line with the excessive centralisation that took place at the Elysée in all domains, the general gained the upper hand over all the other cogs in the military machine: the minister of the defence, the minister's private office, the chief of the defence staff and the heads of the different branches of the armed forces. “It was Puga and Sarkozy who conducted the war in Libya, both in perfect harmony. Puga called the units on the ground directly and he adored that,” recalls one observer, who was in the inner circle at the time. As a result, when socialists who take an interest in defence issues prepared François Hollande's election campaign in 2012, they identified “two guys to get rid of”, recalls one of the behind-the-scenes advisors. “Guillaud [editor's note, the Chief of the Defence Staff] because he was rubbish and Puga because he was a scoundrel.” However, this was clearly not what subsequently happened.

There were several reasons why Benoît Puga was kept on as official military advisor by the new socialist president. The first is that Hollande did not want a witch-hunt on his arrival. “It's republican continuity,” agrees Jean-Pierre Jouyet, secretary-general at the Elysée – in effect Hollande's chief of staff - and a close personal friend of the president. “Moreover, Hollande has always said to me: 'Puga is loyal to me and he is very effective on an operational level'.” The former general Vincent Desportes says the same thing. “Puga's ideas aren't important, it's the republican aspect of our armed services that matters. We are first and foremost the nation's soldiers.”

The former Chief of the Defence Staff Henri Bentégeat explains the situation from a military and political point of view. “When a president takes office there is always a field of operations where something is happening and problems in one part or other of the globe and, very quickly, the chief of the president's military staff must reassure the head of state. And Puga is solid and he knows how to reassure.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

All of which is true, but accepting just this explanation would ignore another important side of the story. A former senior official, who is very well acquainted with the situation, says that Puga and Hollande got on well because of a common link in their pasts; both their fathers associated with the Organisation de l'armée secrète (OAS), the paramilitary organisation violently opposed to Algerian independence from France. Hollande’s father Georges Gustave Hollande, a doctor, stood on an extreme-right ticket in local elections in north-west France in 1959 and 1965 and sympathised with the OAS. There is undoubtedly a link there, but above all it illustrates the propensity of Benoit Puga to be a “courtier”, to use the expression regularly employed by the majority of people who speak about the general. “He's a court priest, he's very obsequious,” says someone familiar with events at the Elysée. “He's the type of person who'll wait in front of his office for the president to pass and then go and join him as if it were a chance encounter.” Another Elysée official says with a smile: “He stays very close, he's always there. He practices court politics.” A third official, who knew Puga before he worked with Hollande and found him an austere and buttoned-up character, says of him now: “He's jovial, he makes jokes.”

When Hollande's team took over the reins of government in May 2012, Puga thought his term of office at the Élysée was over. The new socialist president had nominated one of his own closest political friends, Jean-Yves Le Drian, as defence minister and had expressed the wish to re-establish the institutional order Sarkozy had overturned. So the president's chief military advisor once again became an advisor like any other, not the all-powerful war chief he had been.

When the possibility of an intervention in Mali was on the horizon, Puga adopted a position radically opposed to the one he had held with Sarkozy. “He said to himself, 'I'm dealing with a socialist president and a staff that does not like war and wants to change relationships with Africa', so he sided with those who were opposed to the intervention, like a courtesan trying to please,” says one observer who is very well informed on defence matters.

“While the army and the defence ministry were arguing for armed intervention, he was sending ambiguous orders, saying 'Prepare for action' while simultaneously imposing difficult conditions on the intervention, such as that it had to be a 'clear-cut offensive', a particularly vague term. The army felt Puga was not the right person for it at the Élysée,” this observer adds.

Hollande finally decided to launch Operation Serval with the defence ministry's backing, but Puga bounced thanks to his expertise in managing an external operation – his speciality. Many people say he was influential in the parachute drop by the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment into Timbuktu on January 28th, 2013, seeing it as a way of adding an extra chapter to his former regiment's battle honours and, moreover, doing so at a crucial period when budget cuts threaten various units.

Not everyone agrees on this, however. “People say it was him, but it was François Hollande who imposed [the parachute drop] because he wanted to move quickly,” claims the observer of defence matters. Nevertheless, Puga is back in the fray, even if he must now share decision-making with the defence ministry. The sending of French troops into the conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) in Operation Sangaris completed his return to the saddle.

But the outcome of these two operations in Africa are not entirely positive from a political-military point of view, since the interventions in Mali and CAR, sold as being only of short duration, are being extended ad infinitum. “For the past 15 years or so we have tended to militarise our reactions to every problem. That is due to the weight the chief military advisor carries and the assurance systematically given by the military to the head of state that the intervention will be of short duration,” a presidential advisor says. “Even if politicians are not always taken in, it reinforces their decisions and the military aspect wins the day.”

'He has regained power and is now flying high'

Puga is criticised over the African interventions for two reasons. Firstly, “he does not want to be the bearer of bad tidings and he is constantly trying to anticipate Hollande's opinion, so he is not fulfilling his role as an advisor,” according to an expert in defence matters who occasionally has dealings with him. Secondly, he has been able to establish himself as an Africa specialist at the Élysée, not only because of his military record there but also because of the weaknesses of Hollande's team on the subject. But “his vision of Africa is that of the colonial period from 1880 to 1960. To him, it is enough to be on friendly terms with African heads of state and their military chiefs of staff to be able to solve all the problems,” says one of his former colleagues, who stressed that he lacks the long-term vision to deal with the rapid development and upheavals the continent is undergoing.

“You can't criticise Puga for only thinking in military terms over Mali and the Central African Republic because that's his role,” says a university specialist on Africa with contacts at the Élysée. “The problem is that the civilians are not up to scratch. Puga's rise is the consequence of this weakness in Hollande's inner circle.” A person familiar with the Élysée confirmed this observation, saying that Hollande no longer has faith in many of his Africa advisors, “but he continues to listen to Puga”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

It is natural that all the president's advisors want to have his ear, and there is inevitably tension when there is more than one of them. But the ministry of defence is currently particularly irritated at the importance Puga has acquired, and his apparent ambition to become Hollande's only defence advisor.

“He has regained power over the past two years and now he's flying high,” says a senior civil servant at the defence ministry. “He truncates the information he passes to the president, he selects the dossiers he passes on to him, and that's unacceptable! He's taking control of the president's brain. He intends to run his own defence policy.”

There are two main grievances against Puga. Firstly, on budget matters, while the ministry of defence is constantly proclaiming that the government must halt defence cutbacks, saying they risk undermining France's deterrent capacity, its ability to intervene and the morale of its troops, Puga is playing the opposite card. “When the minister explains to the president that it is imperative to maintain the defence budget because things are going very badly, Puga goes behind his back, saying it's just posturing, that he knows the army well and that it's not doing as badly as all that,” says the senior civil servant.

The current Élysée secretary general, Jean-Pierre Jouyet, implicitly admits this is the case. “He is one of those who keeps the greatest distance from the military lobby when it comes to budgetary questions,” he told Mediapart. And an Élysée advisor adds: “He's not really at ease with this kind of conflict and has adopted the very singular attitude of saying, 'we will find a solution', while minimising concerns over the malaise in the armed forces.” And here again, Puga is criticised for not fulfilling his advisory role properly and of instead seeking to preserve his own career and personal interests.

Another cited example of this is his backing for the 'regionalisation' of troops in the budget debate, which means pre-positioning forces in Africa. That is costly, and it favours the Foreign Legion, the parachute regiments and the navy, described by a former intelligence officer as “Puga’s gang”, and who welcome such deployments as they offer scope for bonuses and promotions.

The second grievance is that Puga has sought to take over cases involving defence contracts and military-industrial issues, and tried to favour his own networks, though apparently without much success. The presidency is the fulcrum through which all decisions concerning the French armaments industry, and the dovetailing of them with national and diplomatic interests, must pass, with hundreds of millions of euros and personal contacts at stake.

Going back to the Sarkozy era, the chief military advisor was charged with managing a major arms contract under the aegis of the then Élysée general secretary, Claude Guéant, bypassing the defence and industry ministries. But, according to a specialist in this type of negotiation, “that can't work unless everyone is on board and inter-ministerial relations function properly. When you give the task to one man, he stays inside his own networks and does not go further. The result is that Puga did not sign a single arms contract.”

'He has the paratrooper's obsession with finding somewhere to land'

Under Hollande, Puga nonetheless continues to handle this sensitive area of defence contracts, one in which the president's intervention is constantly being sought. And unlike the defence and industry ministers, the president’s chief military advisor is always at the head of state's side, particularly during foreign visits. But in this area, too, Puga is accused of only doing part of his job. “He's only interested in prestigious contracts, missiles and Rafales [editor's note, jet fighters], because it is rewarding, there's a lot of money involved and the industrialists speak directly to the president,” says the senior civil servant at the defence ministry quoted earlier.

For the rest, he selects dossiers on the basis of his own criteria, which annoys the industrialists and they are now trying to circumvent him. According to an advisor at the Élysée, Puga has also on several occasions avoided taking a decision over armament programmes that directly concern the French armed forces. “He expressed no preference for such or such a programme. Yet it's imperative that the military buy into these [programmes] as they are the oens who stand to benefit from them, or not, as the case may be, particularly in this period of budgetary restrictions. Civilians cannot make the choice of armaments for French regiments by themselves!”

For the past two years socialists who work on defence questions have held their tongues. “Puga benefits from a code of silence at the Élysée,” one of them told Mediapart. But this no longer holds. Some of them have become fed up with what they call “François Mitterrand-style management, which imagines that protecting people from the opposing political camp confers grandeur”. Others simply believe that the job of chief military advisor is an eminently political job, and that it is not acceptable that someone with such right-wing ideas and sycophantic manners should occupy the post. On top of that, Puga has passed the usual retirement age for the military – in 2014 soldiers born in 1956 were eligible for retirement; Puga was born in 1953.

But yet another group see Puga as a real problem, an advisor who is not fulfilling his role and who, after the president's reshuffle of his staff following socialist defeats at the municipal and European elections, may well consolidate his influence even more. “[Defence minister] Jean-Yves Le Drian has to go round him to present his cases to the president, and he recently said to his face during a meeting with Hollande that [Puga] was not fulfilling his role,” says one socialist. “He is playing the role of a selective filter and the problem is that Hollande does not realise this.”

It is by no means rare to see presidential advisors under the Fifth Republic carving out significant fiefdoms and provoking jealousy or irritation from others. But Puga's position, given that he is not a close ally of Hollande, given that France is involved in at least two major military operations and because he remains a secretive person who reports to no one but the president, remains questionable. One lawyer who specialises in African questions says with irony: “He has bewitched Hollande.”

One thing is certain: Puga is hanging on to his position and, according to people who know him, he “wants to stay right until the end” of this five-year presidency. Other, less generous, observers say he suffers from “the paratrooper's obsession, that is, of finding somewhere to land”. One defence expert who mixes with him says that he “has a taste for power and prestige, and it is out of the question for him to leave without having another job to go to. But, in doing this, he blocks the entire top military hierarchy to satisfy his ambitions”.

Puga missed the opportunity to become chief of staff of the Armed Forces in a reshuffle in February this year – that went to de Villiers – and he might have wanted to go to ODAS, the company that manages major arms contracts for the state, but de Villiers' predecessor, Admiral Édouard Guillaud, was appointed to that job and does not intend to forego one of the French Republic's juiciest salaries. Puga could become grand chancellor of the Légion d’honneur, but he would have to wait until 2016 for that and the post is essentially honorific.

“At the moment he's thinking of becoming an ambassador like his friend Emmanuel Beth,”says a socialist who specialises in defence issues and does not particularly like Puga. “He has been very careful to build an image of himself as a war leader and a warrior monk, but he is self-serving and a profiteer. In that, he is the incarnation of the Sarkozy-ism that got him this job: always needing to have more, to try something more.”

On this, as on so much else, François Hollande has neglected to make a clear break from his predecessor.

--------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article is available here.

English version by Sue Landau and Michael Streeter