Laurent Dias does not have a business card, just bits of paper on which he can scribble his contact details. His message: "Here’s my number. Call me if you want us to look at your pay slip together. You have rights and you should be paid the same as a French worker according to the rate for your qualifications."

Dias, a plumber by training, heads the Auvergne section of the construction branch of the Confédération générale du travail (CGT), one of France’s biggest trade unions. He was born into a Portuguese family who came to France in the 1960s, and now he spends his time criss-crossing the Auvergne region in central France to hunt down abuses of temporary workers employed on building sites, whom he says are "paid like slaves."

He tracks down Polish metal workers, Portuguese bricklayers and Romanian welders, among others, and organises raids of sites not unlike police raids. He targets large and small operators which appear to have plenty of imagination when it comes to paying workers as little as possible, and alerts the official Labour Inspectorate to their practices.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Such workers are sent to France from other European Union countries on temporary postings, but their pay and conditions often fall far short of what they should get under French rules. This is a practice sometimes described as social dumping.

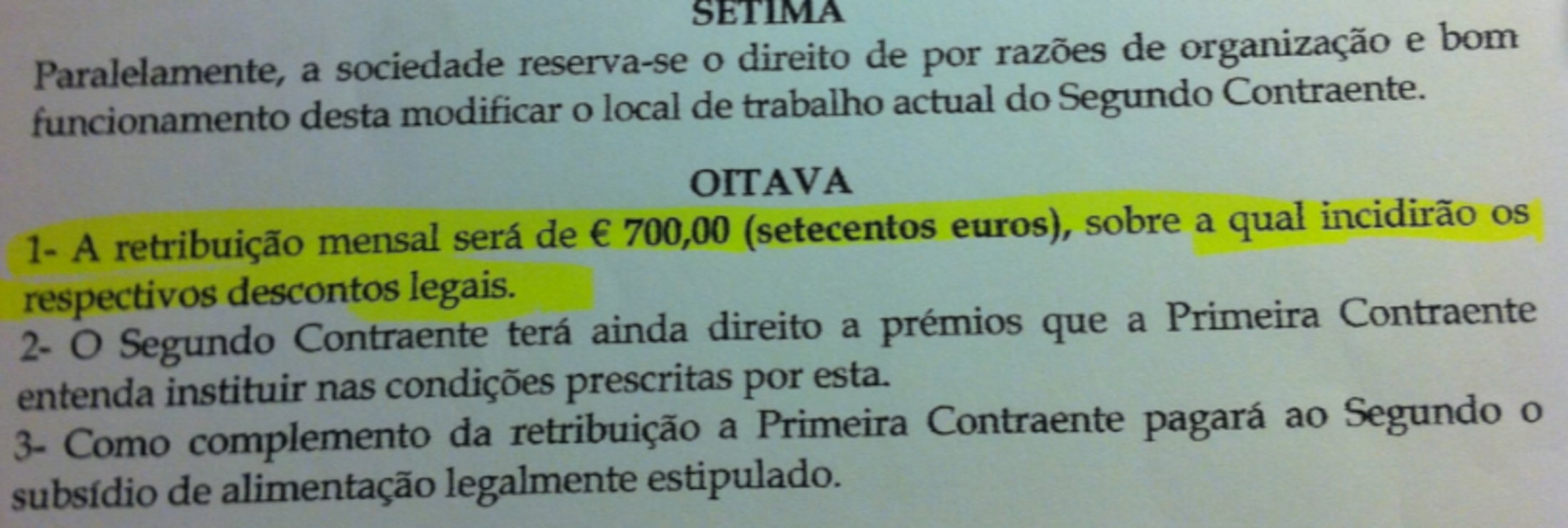

Last week, Dias, the CGT construction section's legal advisor and a law student headed for Cournon, a small town of just under 20,000 inhabitants south-east of the Auvergne's capital Clermont-Ferrand. They were investigating a report that ten Portuguese workers had been posted to a building site there by a Portuguese temporary employment agency and were being paid 700 euros gross a month for 40-hour weeks - or about four euros an hour- which is supposed to cover lodgings, meals and transport costs as well as wages. He had received a copy of their contract the previous day.

Dias was worried about whether the workers would be on the site when he got there. Often he has to visit several times before being able to make contact, as either the workers in question are absent or because they are afraid to talk to him, fearing they will be summarily sent back home if they do.

But not this time. The Portuguese temporary workers, all from Braga, Portugal’s third largest city, are sitting in front of the prefabricated huts that serve as a canteen. Their home region in the north-west of Portugal is suffering from high unemployment and the building industry is particularly hard-hit. They are finishing their lunch, sitting separately from the local workers.

Dias can spot them several yards away by the worn jeans and shoes they wear. "They look like tramps compared with the automatons in blue overalls who get new work clothes every year," he says.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

It takes a few minutes to break the ice. It helps that he speaks Portuguese. Manuel (his name has been changed for this article), a man of about 50, is pleased to see a trade union representative and confirms the pay rate Dias has been told about. Chain-smoking cigarette after cigarette, he repeats: "França, païs de banana" (“France is just a banana republic”).

Manuel is the angriest of the group and has the best grasp of French rules. He is happy to show Dias his pay slips, and says he earned better money in Spain, where he worked for 15 years. "There, the Labour Inspectorate doesn’t waste time. They record the offence directly with bosses who don’t apply the law on building sites."

But the youngest of the group, Roberto (whose name has also been changed for the article), cautions him not to show Dias his pay slips, "or else be sent back to Portugal." Dias is not surprised. "These guys live in fear. They know they are in the firing line. Consulting a trade union means risking being sent home." He gives them his contact details and leaves. He is far from sure they will take the matter further.

Mediapart contacted their employer, who has about 30 employees. He appeared to be astonished when presented with a copy of the contract and assured us he did everything by the book. He promised to look into the practices at his subcontractor and to halt the contract if necessary.

He said he had been unaware of the Portuguese workers' remuneration. "We don’t have much information on their contracts. Everything is done in Portugal according to the law there. We don’t get involved," he said.

It was the first time he had used this type of subcontractor, and had done so on the recommendations of other entrepreneurs who have done so for years, he said. "We're all doing it because the deadlines for finishing a job are getting tighter and tighter. It’s to avoid penalties, not for the money. We're not making money on it, just a small margin," he said, adding that he was only copying the big building firms.

Polish or Portuguese workers going cheap on the web

The number of temporary work assignments has mushroomed in Europe since the Bolkestein Directive was adopted in 2006, creating a single market in services in the European Union. Then, with the economic crisis, the phenomenon has intensified, and not only in frontier regions.

The number of transnational postings declared in France rose to 35,000 in 2009 from just 1,443 in 2000. But this is only the tip of the iceberg, according to a report from the French parliament’s Commission on European affairs presented to the National Assembly (the lower house of Parliament) in February 2011. Only a third of such postings are declared, and the report estimates that over 300,000 people are concerned.

The phenomenon has become commonplace in France and has given rise to all kinds of fraud, from lack of social and health cover to minimising tax liabilities. In labour-intensive sectors such as construction, agriculture or catering, these cheap nomadic workers are increasingly favoured by small and large companies alike. They often cannot find a job in their home country, and their attributes are advertised and vaunted on the internet.

They are brought in via service providers, sub-contractors or foreign temporary employment agencies. These specialists know how to get around even France's complex legislation, for example by ensuring that the posting lasts for fewer than three months, which means the workers are covered by labour law in their own countries, not French labour law.

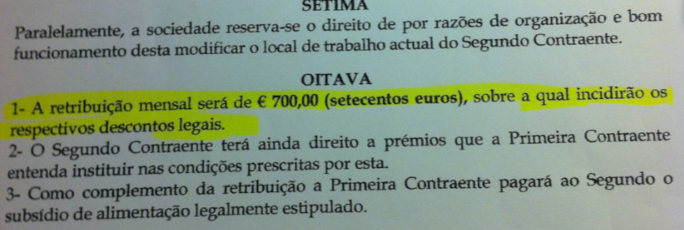

This has become a business in its own right. Temporary agencies and companies carrying out structural building work can easily be found online promising the lowest prices for labour, such as this advert poorly written in French for Portuguese workers in building trades (see below) and this Polish agency.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Often, foreign workers on temporary postings are in the majority on prestigious building projects without anyone seeming to be concerned by the fact that their work, salaries and living conditions go against French law. One senior workplace inspector who is “overwhelmed by the scale and complexity of the phenomenon” told Mediapart that there were many examples of what he called "skullduggery" to bring low-cost labour into the French building trade.

These include shell companies in Luxembourg set up to avoid paying social security contributions, and companies in Eastern Europe with a postal address and no real activity "specially set up to mop up labour at low prices, mostly paying the hourly rate in the home country," he said.

His service is "powerless, overwhelmed, not always backed up by the prosecution authorities despite evidence of the offence of illegal, labour-only subcontracting (1)”, he says, asking to remain anonymous. “Using archaic inspection methods dating from the Cro-Magnon era our officials cannot fight against an opaque system that uses the internet, several countries and more complex legislation,” he says. “It's not through using conventions on cooperation with neighbouring countries that the problem can be sorted. All that takes a ridiculous amount of time compared with the the speed of the real world. Between the time that an inspector inspects a site and him coming back with an official court-approved interpreter, the exploited workers have already left!”

In the local offices of the Directions régionales des entreprises, de la concurrence, de la consommation, du travail et de l'emploi (Direccte) – which are decentralised regional departments covering issues such as industry, employment and tourism as well as work-place conditions – the public sector reforms carried out under President Nicolas Sarkozy have left their mark. There are barely 1,200 workplace inspectors for the whole of France and they say they are helpless faced with the convoluted and time-consuming cases they are confronted with, which are hard to track down and prove.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“I should spend two months on each case, and I should be able to travel to Poland, Switzerland or the Pyrénées, according to where the sub-contractors are based, so I can work out the chain of responsibility, but I am not a police detective,” says one “angry” inspector, who is not allowed to “go outside his area”. He has still not heard any news about evidence in a case he passed on to the judicial authorities a year ago. The inspector says that a sign of his profession's concern is that the subject forms the biggest discussion group on their internal intranet, after the issue of the 35-hour working week.

All over France, according to their branches, the unions Force Ouvrière (FO), the Confédération française démocratique du travail (CFDT) and the CGT are taking up the issue and denouncing these “Mafia-like networks that work like drug traffickers”. This summer the workplace inspectorate stopped work for a while on the building of a new stadium in the Mediterranean city of Nice, which is a public-private partnership, after the death of two Polish workers just a few days apart.

“One of them, aged 54, had a stroke while the second, who was 64 and responsible for safety, had a six-metre fall,” says Miloud Hakimi, the CGT representative on the works committee at building group Vinci. “They were employed by a society called Lambda based in Warsaw, sub-contracting for a businessman from [the French southern city]Avignon, who was himself a service provider for Vinci. They were working there to pay off their mortgages. The Direccte for the Alpes-Maritimes [region] did not let it drop. They forced Vinci to make sure the Polish sub-contractor paid everyone according to the French building industry collective agreement.”

The CGT's construction sector federation has now decided to declare war on unscrupulous sub-contractors. On November 12th it assembled 1,500 delegates at La Plaine Saint-Denis (in the Seine-Saint-Denis department to the north-east of Paris) and raised the issue of foreign sub-contractors. The location was not far from a huge worksite that has itself come under suspicion, the headquarters of mobile phone and internet operator SFR.

With the National Committee on the Fight against Illegal Working (Commission Nationale de Lutte contre le Travail Illégal ) meeting on November 13th under Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, the union's aim was to draw government officials' attention to a problem they say “pushes down wages and exploits the most vulnerable”. The CGT is also holding a national conference on the issue on December 4th.

The union says it has written endlessly to the big players in the construction industry, Vinci, Eiffage and Bouygues to alert them to the situation, but in vain. “They are all against it when they talk, but when it comes to deeds they are all adept at social dumping,” claims Éric Aubin, head of the CGT construction federation. He is calling for a number of measures to be implemented. “French law should be systematically applied to foreign sub-contractors, sub-contracting should be restricted to two levels, the tax and social responsibilities of service providers should be tightened, and work-place inspectors should be given more resources for their inspections,” he says.

--------------------------------------------

1: The French term is 'marchandage' which refers to any sub-contracting of workers which deprives them of their legal rights. It has been an offence since the nineteenth century.

'If you look at the written texts, it's a perfect world, but...'

Laurent Dias, secretary of the CGT construction federation in the Auvergne, will be present at the conference, as his region in the centre of France has its share of frauds. “What is happening in Clermont-Ferrand is what's happening a thousand times greater in the big cities,” he says. The workplace inspectorate there does not have a dedicated “illegal work” section, as do its counterparts on the Côte d'Azur in the south of France and in the Paris region. But it is not short of work.

In the town as in the countryside, businesses affiliated to the main employers' organisation in the construction industry, the French building federation, officially staunchly opposed to 'social dumping', use the services of international providers, mainly from the Iberian peninsula and Eastern Europe.

“If you look at the written texts, it's a perfect world, but no one takes any notice of them,” says an angry Laurent Dias, back in his office in Clermont-Ferrand. He shows the cases that are in the process of ending or will end “marked as no further action, like the others”. The case of Carré Jaude II, ( http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centre_Jaude_2 )a huge commercial and residential complex developed by Eiffage in Clermont-Ferrand, has concerned the union for some months, but they have not been able to prove any breach of the law. However, according to the CGT “Poles were paid by the job, per tonne of metal, and the Portuguese were not paid at all”.

These workers had one thing in common. They were employed by the firms ASTP, since placed under a form of court insolvency protection known as Safeguard Proceedings, and Sendin, two companies involved in construction under the control of brothers. Thierry Julien, the project director of the site for Eiffage denies “such practices”. If there had been any use made of sub-contractors from Portugal and from Poland for limited periods, “the papers were in order”.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Laurent Dias is not convinced. He was never able to locate the employees. “There are those who go back to their country or onto other sites, tumbling into the world of clandestine work,” he says. Dias has come up against another difficult case; that of a firm of plumbers who brought in two Poles “in dubious circumstances” via Commerce and communication Polska, a French recruitment agency with a subsidiary in Warsaw. The union official has been unable to “follow the trail”. The website is still active but the telephone number provided no longer works.

According to the firm's former press officer, whom Dias managed to contact after several attempts, the company filed for bankruptcy four years ago. Yet the union official has in his possession a contract for a Polish worker for a position as a plumber signed by this agency at the start of September 2012.

“The director must have kept the commercial branch in Warsaw,” said the embarrassed former worker, before hanging up on Dias. Well-known in Clermont Ferrand, the young boss of this agency - which has attracted the attention of the workplace inspectorate – could not be contacted. Mediapart has tried several times to reach him but without success. The employer who called on his services attempted to put us in touch with the man's business associate, a woman named Justina, but the trail simply led to an answer machine in Polish.

This employer, who is trying to avoid any trouble, defends himself by saying he “got caught up in the [worker] trafficking”. He adds: “They won't get me a second time. The sub-contracting cost me more than using my own guys, [the foreign workers] don't speak a word of French which creates tensions on site and they scarcely work any better [than French workers].” The businessman says he tried out “foreigners” because he was “pestered by emails and by calls from Polish people” and because “the French no longer want to work, or rather they all want to be on 25 euros an hour”.

Laurent Dias's phone rings. He is told about a new “dubious” worksite. This one concerns a public hospital that is being renovated, with “yet again Poles and Romanians being paid at the minimum wage of their own country”. Dias feels very aggrieved. “When the big construction firms take their French executives on secondment to Portugal, they are not subject to Portuguese minimum wage levels,” he says. “We have a single currency, we should also be able to have a single set of social rights.”

-------------------------------------

English version by Sue Landau and Michael Streeter

Editing by Michael Streeter