In the memory of living political journalists, there has never been anything like it. Here is a major figure in the French presidential election race who has become embroiled in a scandal that prevents him from effectively pursuing his bid, and yet who can still win the contest.

François Fillon can no longer get about France, this country he longs to govern as president. He can hardly take a step without meeting people who compare his manifesto with his acts, and who greet him by beating a spoon against a saucepan – called a casserole in French, which is also a colloquial term to describe a scandal that clings to someone.

He is a man who has varied his position since the media disclosures last month that, as an MP and senator, he used public funds to employ his wife and two of his children for jobs allegedly under false pretences – in short, for jobs that were fake – and which prompted, on the day the first revelations, the opening of a preliminary investigation by the public prosecutor’s office. Denying the claims, he began by saying he placed his confidence in the justice system while lauding its swift reaction, before calling into question the rapidity of the move to open the investigation; early on, he pledged he would stand down as presidential candidate if ever he was to be placed under formal investigation over the affair, before then declaring that it is only the judgment of universal suffrage, in the form of the two-round election vote, that he would accept.

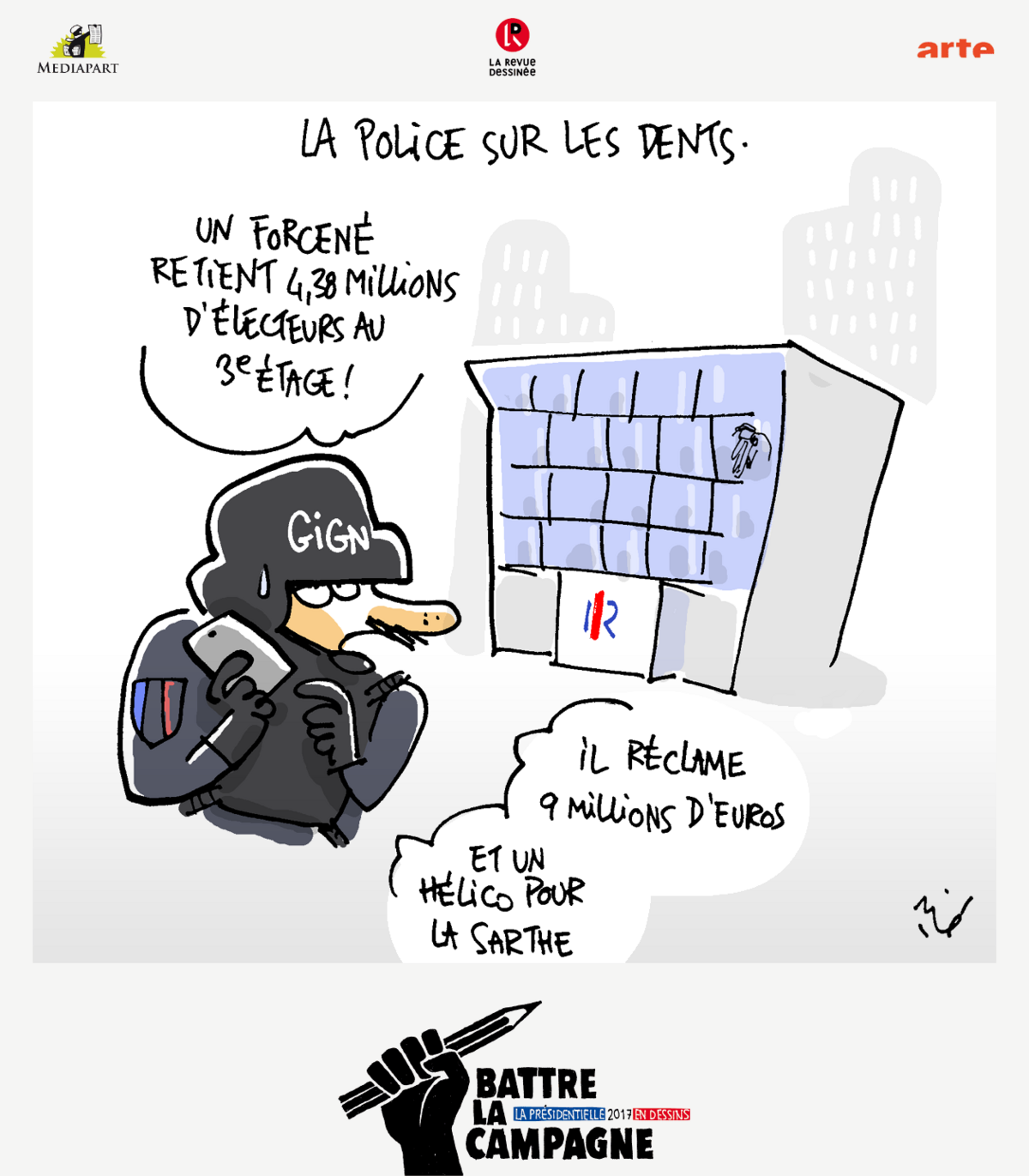

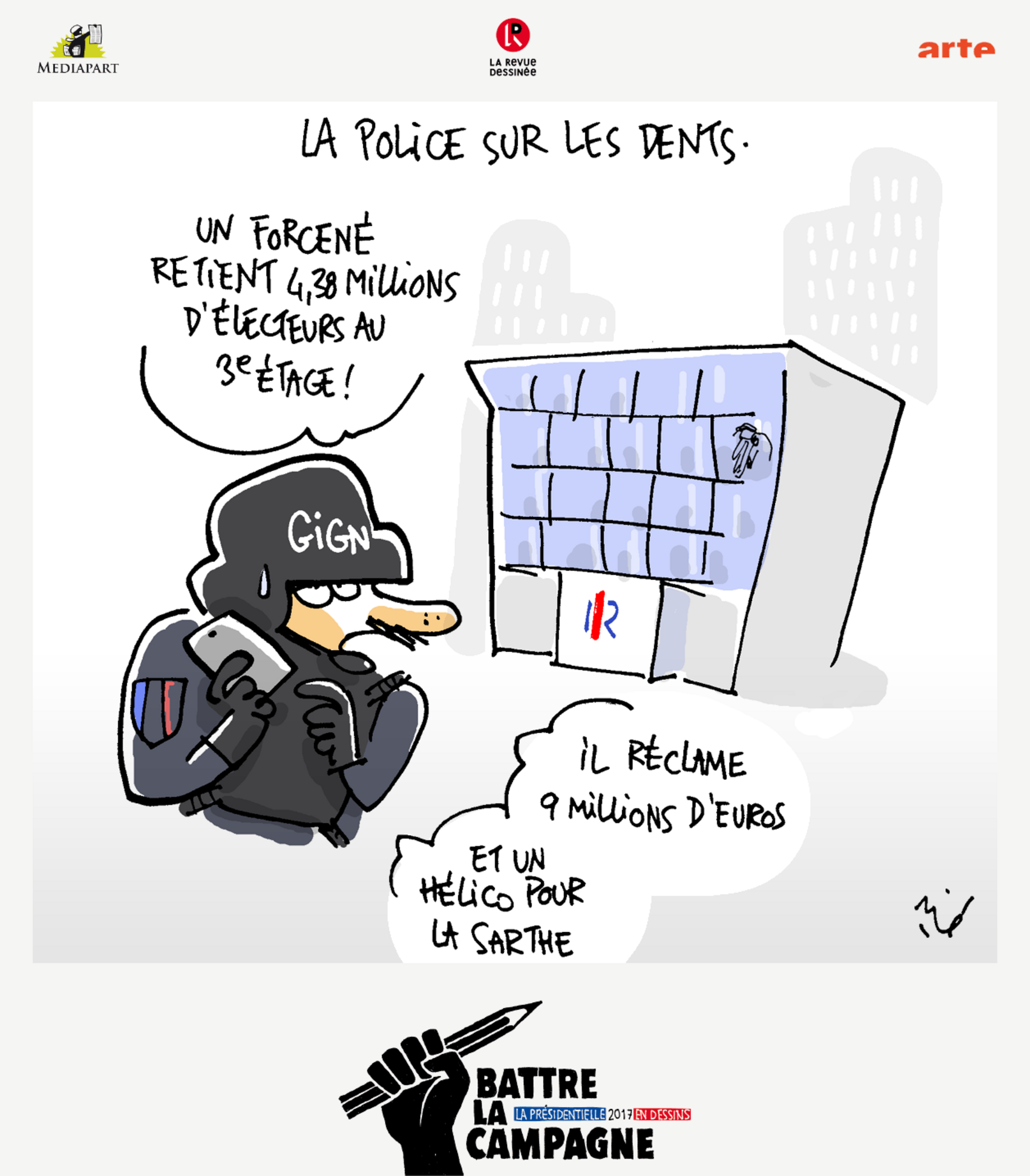

Enlargement : Illustration 1

He has plans to hold press conferences on given issues, but without accepting questions from journalists. He has encountered great difficulties in holding public meetings, cancelling some public events while organizing a closed-door meeting with Nicolas Sarkozy, his defeated rival for the conservative Les Républicains party nomination, and under whose presidency he served as prime minister. As the yearly agricultural fair in Paris looms, a major event in the political calendar when politicians traditionally court the favour of the farming world, his entourage is grappling with the prospect of photo calls with the cows, the calfs and the pigs without some enraged Perrette-the-milkmaid upsetting the pot of his plans, as in the fable by Jean de La Fontaine.

In short, Fillon can adopt all the stances he wishes, and swear that he will resist what he has denounced as a media, judicial and political conspiracy, he remains up against the facts of the case, and those facts are burning his campaign to the ground. His party’s activists are facing this reality almost every time they canvass for him on street markets – the hellish conditions of his campaign is not about others, it is about him. In a fable about the nasty one who attacks the kind one, François Fillon plays both roles. He is the self-tormenting Heauton Timorumenos, that mythological animal which Charles Baudelaire wrote of in his 1857 volume of poetry Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil): “I am the wound and the dagger! / I am the blow and the cheek! / I am the members and the wheel, / Victim and executioner!”

So Fillon has been knocked to the ground, his campaign floundering, and everything that he might say or do should in all logic be worthless. But under France’s Fifth Republic, the current constitution founded by General Charles de Gaulle in 1958, logic has reasons that reason does not recognise. Fillon can no longer be a full-blown, wholehearted candidate, that is an established fact, but he still has a good chance of becoming the eighth French president, and to remain so for the length of the five-year term.

Why is this so? It is for reasons of arithmetic which are proper to French institutions. Ever since this Jansenist of public spending was caught out as being the generous employer of his wife and children, his popularity in opinion polls tumbled to historically low levels for a presidential candidate representing the mainstream Right. Speaking before his party’s Members of Parliament (MPs), he claimed to have stabilised the freefall at between 17%-18%. But one must remember that in March 2007, then-presidential candidate Nicolas Sarkozy scored 31% of voting intentions in opinion polls, and that in February 2012 Sarkozy, then standing for re-election (he was to lose against François Hollande) was on 27%.

The comparison with François Fillon’s current situation places him clearly in the cellar. But he can still rise up to the summit. Without playing at being a soothsayer, it is quite possible, and even probable, that the first round of the elections, on April 23rd, will see the two top-scoring candidates who qualify for the second round playoff on May 7th emerging from a neck-and-neck position of candidates who garner around as little as 20% of the vote. Fillon is not the only one to hope to be among them, but he is nevertheless potentially capable of qualifying. It would suffice to obtain one fifth – or little more – of votes cast in order to become the next French head of state and to dispose of total political power (or what’ is left of it given the functioning of the European Union and the way of the world).

Such is France’s presidential election system, devised by a grand military figure, and which was supposed to rid the country of the schemes of minorities and middleground parties. Instead of establishing an iron-solid majority, so it is that the current French electoral system, almost six decades after it was introduced, favours magical minorities. Former president Jacques Chirac opened the path by twice (in 1995 and 2002) winning the elections after garnering just one in five votes in the first round. Fillon is now clinging on to the branches on the rock face in the hope of clambering back up to the summit of the cliff, and his possible election would be less like reaching the Capitolium from the Tarpeian Rock, than that the Elysée Palace would be facing the doors of the criminal courts.

Before Fillon is the paradoxical perspective of the victory of a knocked-out candidate, and there is something amusing in his claim that “It is a choice between me or chaos”. But his party’s MPs have examined the situation and the conclusion is clear. Fillon may be severely handicapped, but getting rid of him would open up a succession battle that would threaten to decimate the Right just one month before the deadline for election candidatures.

Remaining as a candidate, even with an obstructed campaign, with few public meetings, sheltering from the embarrassment of the clatter of saucepans, and with the justice system and the press on his back, there will always be an incompressible hardcore of rightwing voters to support him. They will sulk, drag their feet, but they will swallow their disillusion in order to avoid the victory of maverick centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron, or that of socialist candidate Benoît Hamon, not to mention the spectre of the radical-left's Jean-Luc Mélenchon. This conservative hardcore is capable of placing in power their party’s laminated nominee, already more weakened than an outgoing president, for the single importance for them is to capture the Elysée. The election of François Fillon would be the ultimate wayward drift of the Fifth Republic, that of an obsession with the presidency, and the impotence of the holder of that office.

Unless, of course, that by the force of such absurdity another political aberration should meet with general agreement: if so, far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, even in her wildest dreams, could never have hoped for such reinforcements.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse