For Christophe Sauvé, “one must always put life there where there is death”. Sauvé is a Catholic priest and chaplain for the gypsy community, into which he was born, in the diocese of Nantes, in north-west France. For the past ten years he has painstakingly researched through the diocesan archives to create a register of the names of those from the community who died in the region where one of France’s shameful wartime secrets was, in 2016, finally officially recognised.

In one of the wings of the vast and imposing old building that houses the diocesan archives, situated in the centre of the town of Nantes, are kept the parish registers of Moisdon-la-Rivière and other villages in the Pays de Châteaubriant, a largely rural area, in the north-east of the local Loire-Atlantique département (county), and which surrounds the small town of Châteaubriant.

Between November 1940 and May 1942, during the German occupation of France, 567 adults and children from the Romany gypsy population were held at a concentration camp at Moisdon-la-Rivière, known as the “camp de la Forge”. Rounded up by French police under the orders of the collaborationist Vichy puppet regime led by Marshal Philippe Pétain, the “nomads”, the term applied to them and other itinerant groups, were kept in dreadful conditions of insalubrity. A small plaque at the site records that the interned families lived “in deplorable sanitary conditions, causing the deaths of several children”.

Between 1940 and 1946, around 6,500 nomads were interned in more than 40 camps in France, most of them in the German-occupied zone.

Until recently, the horror of the camp de la Forge remained largely forgotten after the end of the Second World War, and even unknown to future generations in the region, which is forever marked by another tragedy in the sad history of occupied France; in a quarry close to Châteaubriant in October 1941, in reprisal for the killing of the local commander of the German forces, 49 members of the French Resistance, most of them detained communists and who included 17-year-old Guy Moquet, who remains a celebrated example of the heroism of the Resistance movement, were executed by firing squad. They were chosen from a list of detainees recommended to the Germans for execution by the Vichy regime.

It was while researching newly released public archive documents about the executions as part of her history studies at Nantes university that Émilie Jouand, who comes from the region, first discovered the existence of the camp de la Forge in Moisdon-la-Rivière. She chose to write a memoir on the subject, which was published in 2006 under the title La Concentration des nomades en Loire-Inférieure – ‘The concentration of nomads in the Lower-Loire’, the former name of the département.

For Jouand, the fate of the gypsies became obscured due to prejudices that continue today. “The history of this population in particular was made forgotten, because of their way of life, because of the absence of academics among them, and because they are victims of prejudices which still exist,” she told Mediapart in an interview last year (sound extract below).

“That’s to say, who is interested in the lives of French ‘travellers’ today? […] Who is interested in their history? And then, it can sometimes cause fear, because they are not the only groups who fell victim to that […] You can find front pages of [former wide selling French daily] Le Petit Journal from the beginning of the 20th century where they are treated as petty thieves, the children as robbing chickens, prejudices which are well rooted since way back in French memory and mentality, and which continued after the war.”

“To properly understand how things came to such extremes,” said Jouand of the camp de la Forge and the other internment sites for “nomads” across France, “one must see the context of a French state which took advantage of the reigning tensions with Germany to create a vast system of control of populations which circulated on its territory.”

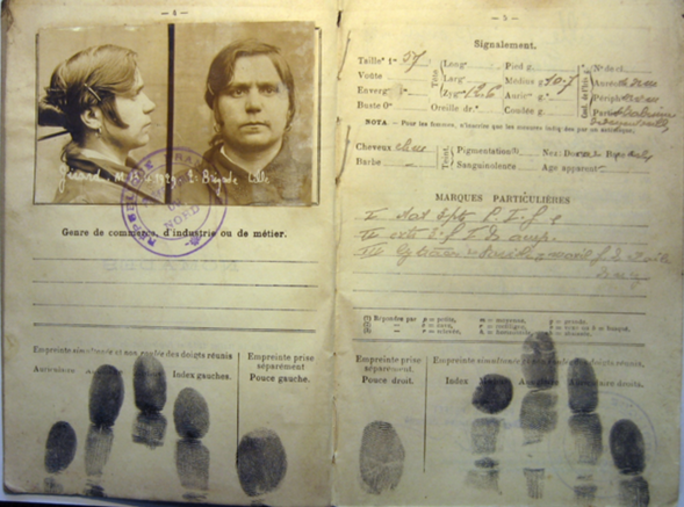

A law regulating the “exercise of ambulant professions and the circulation of nomads”, adopted by French parliament on July 16th 1912, defined three categories of population which were to be issued with anthropometric identity cards that carried frontal and side-on mugshots. These concerned travelling salesmen, whether French nationals or not, and fairground people and stallholders, and “nomads”. The latter were foreigners who were in France to find work or people with no fixed abode, travelling from job to job in industry or agriculture, but also Romany families, many of whose members had been present in France over several generations.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Marcel Laisis, a gypsy in his eighties and a great-grandfather several times over, is a survivor of the camp de la Forge where he was interned with his family when he was four-years-old. He now lives on the “aire d’accueil de la Fardière” in Nantes, a dedicated site for travellers maintained by the town authorities. He recalled the period of the special ID cards. “My family came directly from Italy and I remember very well my grandfather telling me about these collective cards,” he said, to the thrumming backdrop of traffic crossing the bridge above. “Inside, you had to note down the colour of the horse, of the carriage, the vaccinations and a photo of each member of the family, including the children as of five-years-old. It was obligatory, and you had to check in with it to the gendarmerie every day. Every time you arrived and when you left, otherwise – watch out – it’d be an infraction. My father, he did two months in prison for that, for one day when he forgot to show the family ID card. Two months in prison!”

As the outbreak of the Second World War approached, to the sound of marching boots from the east, many families with names that sounded Italian or German fell under increasing suspicion. “Among the Romany, you find different groups who changed their names according to where they lived,” said Emilie Jouand. “The Manouches were in the west of France, the gypsies in the south, the Romanichels in the north-west. The Sinti came from Italy, the Roma from Bulgaria.”

Fearing a “Fifth Column”, the French authorities used the powers of the July 1912 law to move nomad groups from the Paris region into rural areas in the autumn of 1939, shortly after the outbreak of war. It was much like a sort of house arrest on a regional scale. Then, a decree introduced on April 6th 1940, two months before the fall of France to invading German (and Italian) forces, ordered a halt to the circulation of “nomads” on a national scale.

“At a time of war, the circulation of nomads, erring individuals, generally homeless, belonging to no state and without any effective profession, represent, for national defence and the safeguarding of secrecy, a danger that must be excluded,” read the decree. Citing the risk that they could discover French army positions which they would be “susceptible to communicate to enemy agents”, the travellers were to be henceforth placed in “forced residence” under police surveillance.

After the French defeat, and under the collaborationist regime of Vichy, the decree used by the German occupying forces. “This logic of making use of already existing internal laws was practiced very often by Nazi Germany,” commented Jouand. “This had the advantage of getting the local population to more easily accept what were in reality discriminatory measures. In October 1940, the prefects [regional administrative chiefs] in the occupied zone were asked to organise the creation of camps in which to lock up the nomads.”

The prefect of what was then the Loire-Inférieure département (the unfortunate choice of name referred to the “lower” part of the Loire river where it reaches the Atlantic Ocean a short distance from Nantes) requisitioned the camp de la Forge in Moisdon-la-Rivière. The site already existed, having been used between 1937 and 1939 as a detention centre for Republican refugees arriving from Spain in their flight from the advance of General Francisco Franco’s fascist forces during the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War.

The camp de la Forge opened on November 11th 1940. Encircled by the River Don, surrounded by forestland and set within a rock face, this former industrial site was anything but hospitable. Some of the internees were allowed to live in overcrowded wagon-trailors they owned, but many others were confined to unheated dormitories. There was no drinking water nor showers. Food rations were inadequate, just as were medical supplies. Between the end of January and the beginning of February 1941, six infants, all aged less than two-years-old, died in the camp.

'Victory will be when families can complete their grieving'

At the “aire d’accueil de la Fardière” in Nantes, Marcel Laisis, who lives on the campsite with his family for a part of the year, recounted the harrowing conditions of the camp in Moisdon-la-Rivière. In a cruel twist, the modern Fardière campsite for travellers, from where he was interviwed here, which was reopened by Nantes town council in 2014 after renovations to its facilities, was exactly the same site where travellers from around the Nantes region were rounded up in 1940, before they were divided into three groups and sent to separate camps; that of la Forge in Moisdon-la-Rivière, another in nearby Châteaubriant (camp de Choisel), and a more distant concentration camp at Montreuil-Bellay, south of Saumur. All were run by the French gendarmerie, under orders of the Vichy regime.

“When I was in the camp I was four-years-old,” Laisis recalled (play audio above, in French) of his time at the camp de la Forge. “It [the memory of that] is like it was today. The miserable poverty that was mine! We didn’t eat, for entire days. My sister, she was two and a half. We lived in the camp like dogs. My mother was at the camp kitchen collecting the peelings from potatoes, to cook them on the stove so that we could eat – not potatoes, the peeled skins of potatoes. She grilled them on the stove. And for the coffee, it was barley [grass] that she’d pick to cut off the barley [grains]. She’d roast it to make coffee. See the life we had? Do you know what we had for a mattress? The things, you know, for maize. That’s what was in the mattresses. Permission every week to collect wood, with a guard, to light a fire in the forest. With guards, guarded like dogs. The French, ha-ha, the French!”

Annette Fourny still lives in the village of Moisdon-la-Rivière, where she grew up. She remembers seeing the horrors of the camp, from the outside, as a young child. She has never visited the site since it closed, such are the disturbing memories she has. But she accepted to go there with Mediapart, where she spoke emotionally of the scenes she witnessed (audio recording below, in French).

“I can see them all, behind the wire fencing, waiting for us to give them something,” she said, clearly moved to return to the site. “Maybe an egg, but maybe also a word, or a smile, I don’t know. But, a little girl of eight- or nine-years old, I didn’t react as I do today. I can see again what I lived through. To see those children there…whereas we were free, and happy, and above all we had enough to eat. And to see those children who were waiting for something, ouff… It’s hard. These are peculiar memories. Those who haven’t experienced that are not capable of knowing… It’s not possible. I say that you need to have lived through it to…to say it.”

Mediapart caught up with Father Christophe Sauvé as he carried out his research in the Nantes Diocesan historic archives centre. “What was the conscience at those times?” he asked. “Still today, it’s very difficult to answer that question. It points me towards what we are living through now with the migrants. On that question, like others, how will we be judged in relation to our acts? Just look, it’s now 70 years [since the end of the internments], but this story remains so very sensitive.”

The camp de la Forge was closed down in May 1942, but the detention of “nomads” in the more than 40 camps around France only finally ended in on June 1st 1946.

“Once the Vichy regime had fallen, these people remained locked up, simply because they didn’t know what to do with them, and because it suited a lot of people,” said Émilie Jouand. “One could simplify the story by saying 'Vichy was responsible'. In reality, the first concentration [camp] measures on French territory were put in place under the Third Republic [1870-1940] and continued well after the liberation [of occupied France].”

It was not until January 3rd 1960 that the 1912 law that set the grounds for the discriminatory measures was finally repealed. While the anthropometric identity cards were ended, they were replaced by a circulation document. This was a specific ID card, which was issued to those with the administrative description of “travelling people” (in French, gens du voyage). The documents, explained Dominique Raimbourg, president of the travellers’ national consultative commission in France, the CNCGDV, (a body which involves representatives of both the community and government), were aimed at “registering just as much the populations present in France since the 15th century as also those who arrived in successive waves from Germany, Spain, Italy or, today, from Romania.”

The new document was also discriminatory, requiring that “travellers” with French nationality prove they had resided in a locality for a minimum of three years to be able to register on an electoral list, whereas other French nationals are required to live in one place for just six months before registering.

“This designation of 'travelling people' is uniquely Francophone,” argued Bernard Pluchon, a sociologist and administrator of France’s Federation of associations in solidarity with gypsy-travellers (FNASAT). “Whereas other countries make a distinction between groups of Romany, gypsies, in France, not only is there no distinction made but there is a reinforcement of the link made between the practice of a culture of travelling and an ethnic origin.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

On October 29th 2016, then French president François Hollande, during a visit to the camp de la Forge at Moisdon-la-Rivière, officially recognised the role and responsibility of France in the internment of nomads. In January 2017, after a campaign initiated by Dominique Raimbourg, who served for ten years as a Member of Parliament for a Nantes constituency, the requirement for “travellers” to carry the special ID documents was finally overturned by a law, entitled “equality and citizenship”, adopted in January 2017.

Marcel Laisis was present during Hollande’s visit to the camp in October 2016, and briefly spoke with the president. “I told him that beyond the words, we must, in acts, be treated on an equal basis with the gadjé [a gypsy word for non-gypsies], like fully French citizens,” recalled the old man. “I hope he would have heard me. That my sons could be able to live that. In any case, as for me, now, I will be able to find rest.”

“When one talks of internment, of death, there is no victory,” said Christophe Sauvé. “There will be victory when the families are given help to complete their grieving, to integrate their story. I like this phrase from an old ‘traveller’ who told me, ‘The locks must be bust open to hitch up the lives of the sedentary with those of itinerants’. We must connect together to live again, all together, in peace.”

A move in that direction will be the sense of a ceremony at the camp de la forge on April 27th, when a stele will be erected at the site in homage to the 567 nomads and 857 Spanish republican refugees who were interned there.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse