Culture minister Aurélie Filippetti has come under fire from her own political allies for allegedly turning down the chance to visit a former internment camp that will soon become a major memorial site. Christian Bourquin, a socialist senator and president of the regional council of Languedoc-Roussillon in the south of France, is furious that the minister did not take time to visit the Rivesaltes camp while she attended the 'Visa pour l'image' photojournalism festival in nearby Perpignan earlier this month.

Bourquin, who has been a major driving force behind the development of Riversaltes, which is due to open as a memorial in June 2015, did not pull his punches on his blog, with an entry entitled: “Why Madame Filippetti is a walking political disaster.” The ministry of culture hit back at the minister's socialist critics – critics whom it dismisses privately as “embittered provincials” - stating: “The memorial significance of the Camp de Rivesaltes entirely justifies the interest shown by the regional and national governments, but it is unseemly to make it a subject of cheap controversy.”

Filippetti herself strongly denied any suggestion that she turned down the chance to go to the site.

“I have never refused to go to Rivesaltes. I went to Perpignan for the photojournalism festival, which is a normal and important thing to do in a period of crisis for the profession and for the economic situation of the press and photojournalism,” she told Mediapart. “That was the object of my visit and it required time.” The minister insisted that Rivesaltes was being used as a pretext to attack her for other reasons, and said it was “absurd” to suggest she was uninterested in the memorial project.

Filippetti added: “You should know that the Rivesaltes camp dossier is being handled with care by officials at the Ministry of Culture, for as my career shows I attach great importance to the passing on of the memory of those tragic years.”

But beyond the political squabble, the question arises: does the historic interest of the site justify making it a subject of shared understanding, touching on history, living memory and politics? To find out, Mediapart spoke to historian Denis Peschanski - see interview below - an expert on the history of France's internment camps, the author of La France des camps (Gallimard, 2002) and chairman of the scientific board and vice-president of the steering committee - chaired by Christian Bourquin - of the future 104-acre (42-hectare) Rivesaltes memorial site.

--------------------------------------

Mediapart: What do you think of Aurelie Filippetti’s faux pas?

DENIS PESCHANSKI: It seems astonishing to me that she failed to grasp what a symbolic issue she was turning her back on. And yet Christian Bourquin had brought the matter to the minister’s attention. “Doesn’t have the time” was the official explanation. Is Aurélie Filippetti insensitive to memorial issues, to museums and archives? Is she following the regionalist rationale of an elected representative from Lorraine [editor's note, she is MP for the département of Moselle in the Lorraine region of north-east France] by showing less interest in a project far from her circumscription? I can only air hypotheses, noting just one factor, and it’s a big one at that: she’s not the one who has ultimate control over such a project.

Mediapart: Isn’t Christian Bourquin’s outburst just a pointless rant?

D.P.: Christian Bourquin has been behind the project since 1998. First as president of the Pyrénées-Orientales département's general council, then from 2010 when he succeeded Georges Frèche as president of the Languedoc-Roussillon regional council. He has always had to fight to get the national government to carry out its responsibilities, whilst coming up against financial and, above all, political stonewalling. Under [presidents] Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy, the Right, who were dreaming of conquering the Pyrénées-Orientales for themselves, made sure there was no sign of support from the national government for Bourquin, who had to be weakened with an eye to the cantonal elections held every three years. So despite the lip service sometimes paid by the top tiers of the national government, there was no end to the back-pedalling on this project. Especially as one of the main parties involved, the department for war veterans [editor's note, which is in the defence ministry], was probably the one that changed its minister the most frequently. Jean-Marie Bockel, for instance, a socialist won over to Sarkozy’s overtures to the Left [Editor’s note: to join his government], showed a keen interest in the Rivesaltes memorial, but he only remained in office for a year [from March 2008 to June 2009].

Mediapart: But now the set-up is ideal...

D.P.: It’s true that the president of the Senate, Jean-Pierre Bel, is an elected official from the neighbouring department of Ariège, where Camp Vernet was located by the way. It’s also true that the president of the National Assembly, Claude Bartolone, was head of the departmental council of Seine-Saint-Denis and backed the Camp Drancy Memorial that was inaugurated by François Hollande in September 2012. As he showed this month in Oradour [Oradour-sur-Glane,a village in west-central France whose inhabitants were massacred by the Waffen-SS in 1944], the French president is attuned to these memorial issues. This comes after the policy reversal of the Chirac-[Lionel] Jospin era [the French state admitting its share of the blame for official French acts committed during Nazi occupation] as against the line epitomized by [Charles] de Gaulle and then [François] Mitterrand [that the French Republic, Vichy’s first victim, need not apologize for the Vichy government’s decision to collaborate].

I would add, in this institutional set-up, the support for the Rivesaltes memorial provided by the current minister for war veterans, Kader Arif, who was born in Algeria in 1959, the son of a Harki [editor's note, Algerians who fought for the French in the Algerian War of Independence]. So Arif spent a few months at the Rivesaltes camp in his early childhood when his family was ‘repatriated’ to France after 1962.

Mediapart: Rivesaltes seems to have an incredibly multi-layered history.

D.P.: About half of this 600-hectare [1500-acre] military camp, which was dubbed Camp Joffre [editor's note, after General Joseph Joffre who was born in Riversaltes], served as a ‘relocation camp’ for Spanish Republicans who’d fled Francoism from 1938 onwards. In 1940 there were Germans who’d escaped from Nazism. Beginning in 1941, foreign Jews were put here. And the Gypsies who’d been driven out of Alsace-Moselle. After the Liberation, collaborators and black marketeers were incarcerated here, followed by German prisoners of war. The camp didn’t close till 1948, and even then its history continued. At the end of the Franco-Algerian War – this is a recent discovery the archives have just brought to light – hundreds of FLN [National Liberation Front] prisoners were penned up at Rivesaltes, followed by a large number of Harkis between 1962 and 1964, ten thousand of them in all. This was as many as the Jews and Spaniards who were there previously. A TV report put together by Jean-Claude Bringuier in 1963 for the show Cinq colonnes à la une depicts the living conditions at the time for those rural and for the most part illiterate populations. The last Harki families, a few dozen, left Rivesaltes in the early 1970s to be housed in Perpignan.

Deportation and extermination

Mediapart: And the story doesn't stop there...

D.P.: One has to beware of drawing facile correlations, but it’s true that in the 1980s, to be able to finish with the detention centre at Roissy Airport, [then interior minister] Pierre Joxe opened a detention centre in a section of the military camp at Rivesaltes, without any genuine legal basis and without any amenities. I remember around 2005 – Nicolas Sarkozy was interior minister then – how the prefect of Pyrénées-Orientales justified such a centre, pointing up its democratic rationale by contrasting it with the policies of Vichy. The socialist officials on the departmental council, on the other hand, stressed how heavily symbolic the place was, making it impossible to detain illegal aliens there.

The detention centre was finally moved in 2007 to a greenfield site next to Perpignan Airport.

Mediapart: The worst chapter in the history of Rivesaltes occurred in 1942, when it went from internment to deportation.

D.P.: In 1941 in this part of the unoccupied zone, the Vichy government practised a policy of exclusion that corresponded to its convictions about France’s decay since 1789, which it blamed on the Jews, communists, foreigners and Freemasons. They were the root cause of the defeat at the hands of Germany (blaming the military was out of the question!). So ‘pure elements’ had to be rallied around Marshall [Philippe] Pétain, and those which were seen as ‘anti-France’ were quarantined.

But in 1942, [prime minister] Pierre Laval agreed to involve Vichy in the Third Reich’s deportation and extermination system. Hence the infamous line from his speech on June 22, 1942: “I wish for a German victory.” He thought a cooperative France would reap benefits from a Nazi Europe.

The Rivesaltes camp played a special part to that end. It was a card that Vichy then played, agreeing to deport foreign Jews, without a single German soldier on hand, from August to November 1942 [when the Germans invaded the southern ‘Free France’ zone]. And when Laval met Carl Oberg [in charge of relations with French police] on September 2th, 1942, the Frenchman begged the Nazi official for ‘agreed formulas of words’, that is, stock answers to give to diplomats, bishops and a section of the public who were asking where the Jewish deportees were being sent. Laval would not be the harbinger of distressing news, he was demanding something to fob them off with! And during those final four months of the so-called ‘free zone’, in nine convoys setting forth from Rivesaltes, he handed over 2,313 Jews, only a few dozen of whom were to return from the extermination camps. To my mind, this is what makes Rivesaltes a permanent stain left by the Vichy regime. On September 5th, 1942, the Rivesaltes camp became interregional [overseeing the camps in Vernet, Les Milles and Gurs]. [Famous Nazi hunter] Serge Klarsfeld called it “the Drancy of the southern zone” [Drancy, a Paris suburb, was the transit camp in the occupied zone where Jews were dispatched to the death camps, mainly Auschwitz].

Mediapart: What should be done with Rivesaltes in the 21st century?

D.P.: France has gone from having camps with no memorials, to memorials with no camps. To remedy this situation, we need to turn our backs on the eruption of scattered little facilities, like those museums of the Resistance that sprouted up just about everywhere in France in the 1960s. We need sites that will encompass the overall history, with the help of major investment. The former camps at Rivesaltes, Orléans, Drancy and Milles will be important and appropriate memorials. These four memorials will have opened between 2012 and 2015, 70 years after the event!

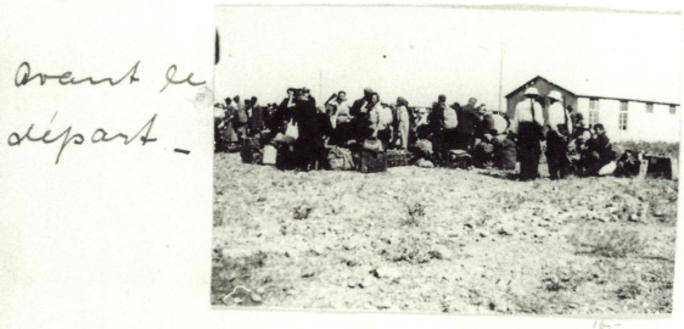

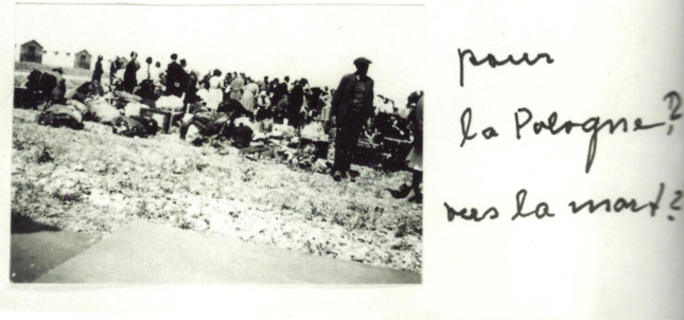

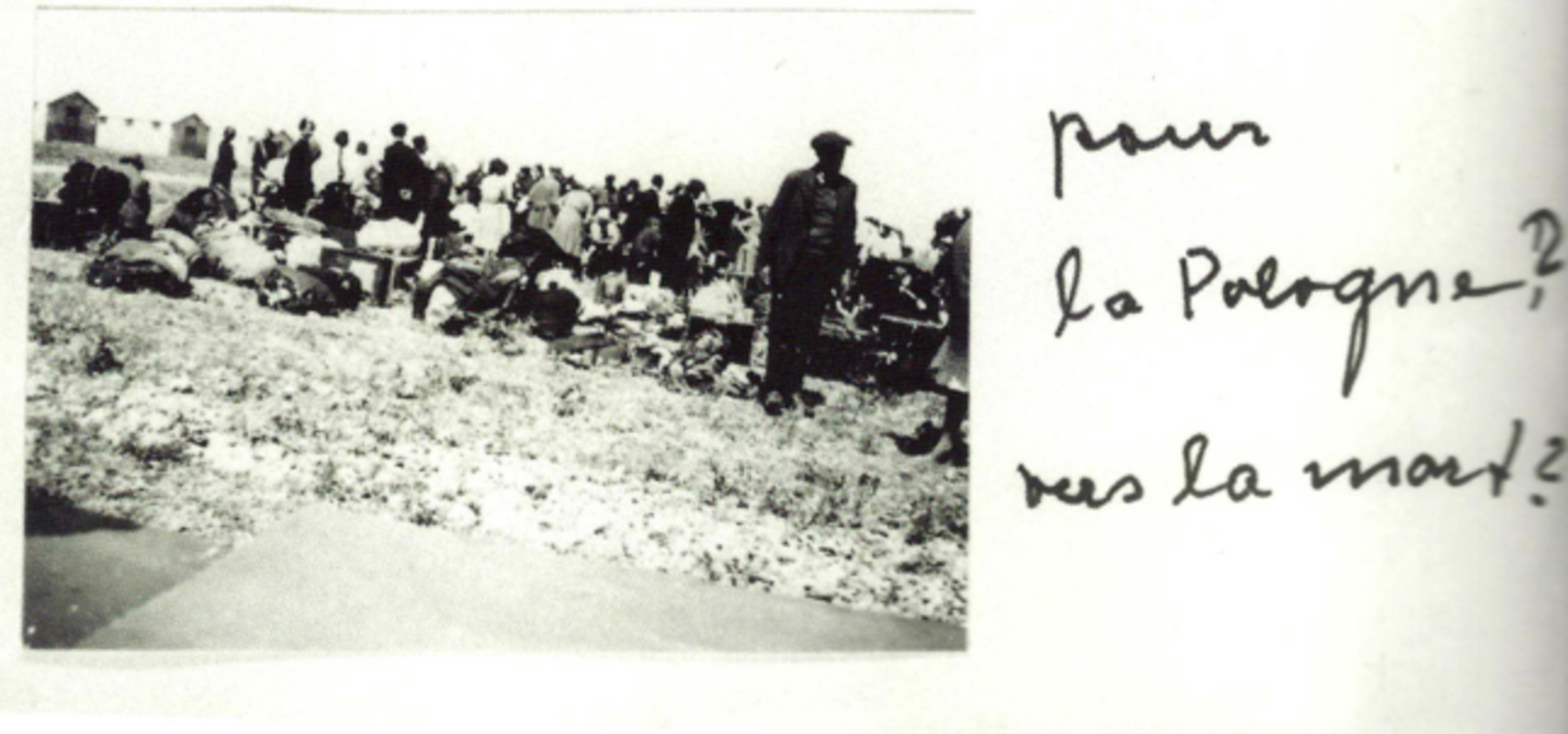

At Rivesaltes, striking photographs will be on display in a building designed by Rudy Ricciotti around barracks that have been salvaged and restored: unique evidence of Jews being rounded up for deportation. These five photographs were taken by the Swiss [Red Cross paediatric] nurse Friedel Bohny-Reiter and [American-born] Tracy Strong [from the European Student Relief Fund].

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart: How do you ensure that there is a close connection between the different memories, and not a form of competition?

D.P.: A few years ago I was invited by the sociologist [and expert on the Harkis] Mohand Hamoumou, who is also a member of my scientific council and who has been the politically independent mayor of Volvic [in eastern France] since 2008, to a Harkis conference to outline the memorial museum project. People were open to the case for a multifaceted history that would attract visitors who had come to find out more about their own past, but who during the trip would at the same time find out about that of others. This shared experience of the rounding up and enforced displacement of peoples seemed to me to be a fundamental, humanist message.

During one meeting the head of an association suggested splitting Rivesaltes into three sections (Spanish, Jews and Harkis). This community-based reasoning, which fortunately was a lone plea, was rejected in favour of what the Rivesaltes memorial is seeking to achieve: the possibility of constructing a common history.

-----------------------------------------

English version by Eric Rosencrantz

Editing by Michael Streeter