During seven days beginning on May 21st 1871, the Paris Commune, the revolutionary regime which had managed the French capital in an insurrection since March 18th that year, was put down in a massacre that became known as “the Bloody Week”.

The Commune arose in the aftermath of France’s defeat in a war against Prussia and subsequent parliamentary elections which returned a large pro-monarchy conservative majority. Paris, which had resisted a long siege by the Prussians, rebelled against the national government and set up its own autonomous, radical-left authority – the Commune – which, during its 70-day existence, decreed an end to capital punishment, announced the separation of church and state, and the abolition of military conscription among many revolutionary measures that also included the prohibition of fines imposed on workmen by their employers and a ban on nightwork in some professions.

The national government, which had fled Paris and sat in Versailles, ordered the regular army into Paris on May 21st, and by May 28th, after fierce fighting, it had regained control of the capital. Around 15,000 of the city’s population died in the ferocious battles. “Every neighbourhood taken by Versailles was transformed into a slaughterhouse,” wrote the Commune militant and feminist Louise Michel. Around 40,000 people were arrested by the army and about 13,000 were brought to trial by military courts.

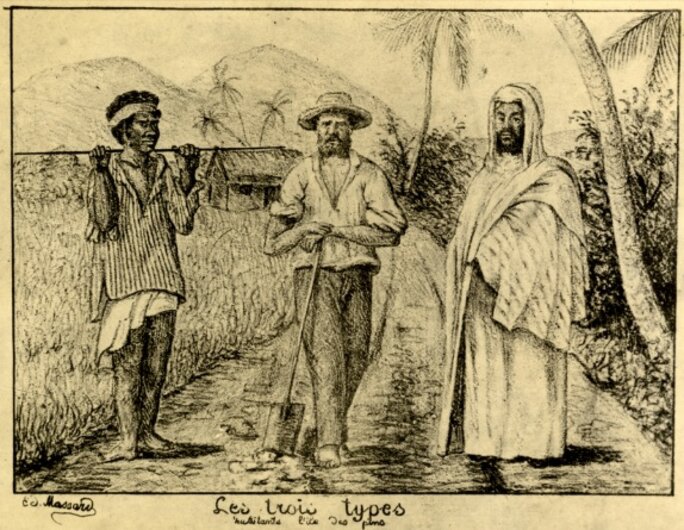

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But despite putting an end to the insurrection, the government in Versailles, led by Adolphe Thiers, was concerned that the revolutionary ideas of the Commune would spread to other cities (as actively encouraged by the Commune itself) and, because execution for political crimes had been abolished in 1848, decided to send thousands of the arrested insurgents to the other side of the world – to the penal colonies on the French territory of New Caledonia in the Pacific Ocean, some 18,000 kilometres away.

During the summary trials, many of the high-profile figures of the Commune, like Louise Michel and the journalist Henri Rochefort, were sentenced to be deported to fortified prison camps, some to hard labour, and others still simply to deportation. Like for the common criminals deported before them, the French authorities hoped that the deported political prisoners of the Commune would also eventually, once having served their punishment, help to build the colony, which had been annexed by France in 1853. For that purpose the deportees were allowed to take with them their spouses and children.

A total of 22,000 people were deported to New Caledonia up until the programme was ended in 1897. The colonial plan was that a large number of those deported would eventually help build up the economy of the islands, primarily with the cultivation of land that the indigenous Kanak population had, it was suggested, been incapable of exploiting. While France rivalled Britain in establishing a vast global empire, New Caledonia, unlike most other new possessions, had attracted few voluntary European settlers.

In the early years of French rule, the archipelago was administered by the navy, whose officials were holed up in the capital of Nouméa. The Kanaks resisted French military operations and incursions on their territories by Europeans with ferocious counter-attacks, leading to a self-perpetuating series of repression and revolts. In April 1858, a report to the French Ministry of Algeria and the Colonies by the French military commander in Nouméa complained that, “There has still been no serious settler to have presented themselves in New Caledonia, there exists only shopkeepers and innkeepers,” adding: “Just one man is an exception, and I have the regret to tell you that he is an Englishman.”

In 1861, French naval officer Charles Guillain, who was appointed governor of New Caledonia one year later, wrote a study proposing to establish penal colonies in the archipelago, in which he argued that without establishing deportations of convicts to the islands “our oceanic possession will have no serious utility”. What were euphemistically called “transportations” to New Caledonia began in 1864.

More than 4,000 former Commune militants were sentenced to deportation, but many spent up to two years languishing in jails in the southern French port of Toulon, on the western islands of Île de Ré and Oléron, and at Quélern near the port of Brest in Brittany, waiting to be sent on the four- to six-month boat journey to the South Pacific.

Some of those temporarily held in the French jails were to discover unexpected fellow prisoners. “We have here around 40 Arabs dressed in their [national] costume,” wrote a young imprisoned former Communard militant, Henri Messager, in a letter to his mother dated May 17th 1872. “I can assure you that we have here quite beautiful men and we appear like not very much beside them […] Among them are several dignitaries who are richly dressed […] Neither the ones nor the others want to believe that they are destined to leave for New Caledonia, they all make out that they would die before arriving.”

The “Arabs” in question had taken part in a revolt in Kabylia in 1871, one of the most important insurrections against French rule in its North African colony of Algeria which it had began occupying in 1830. Among the principal causes of the revolt was the dispossession of many Kabyles from their land and the failure of recent agricultural crops. Some have argued that it was also fuelled by resentment at the automatic granting, in a decree in France in October 1870, of French nationality to the native Jewish population in Algeria, to the exclusion of the Muslim and Berber populations, although the claim is disputed.

The revolt in March 1871 was led by the Mokrani family of aristocrats from the east of the country, allied with their former enemies, the Rahmaniyya religious fraternity led by Sheik El-Haddad. In the subsequent French repression of the rebellion, Sheik Mohamed El-Mokrani was killed in May 1871, while his brother Bou Mezrag and Sheik El-Haddad and his son, were captured. Like some of the Commune militants, a number of the rebels were tried like common criminals and Bou Mezrag, who assumed the mantle of his dead brother, was sentenced to death. Others were sentenced to deportation.

In July 1871, Paris Commune militant Jean Allemane, jailed in Toulon awaiting deportation to New Caledonia, recorded the arrival of the Algerians. “I have learnt that those arriving were, like me, defeated and were treated in the same manner,” he wrote. “The war councils in Algeria competed in zealousness with those of Versailles […] Night approached: sombre and silent, the defeated from Algeria and the defeated of the Commune, sitting side-by-side with each other, thought about those they loved, about the collapse of their existence, about the destruction of their dream of freedom.”

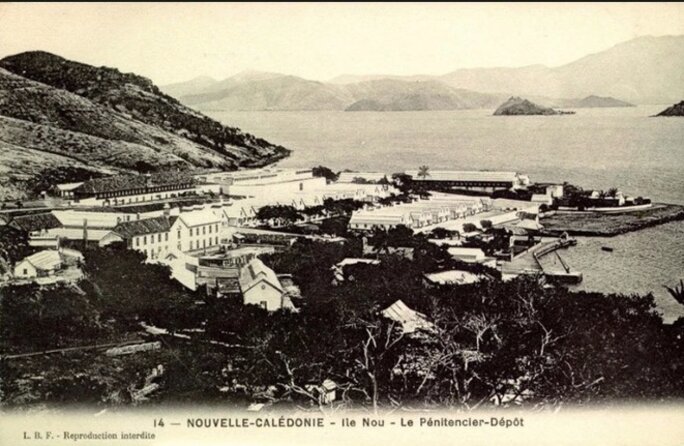

Enlargement : Illustration 2

During his long political career after returning home from the Pacific Ocean colony, Allemane served as a Member of Parliament (MP) and helped to found the CGT union (now one of the largest cross-trades unions in France), and also the French Section of the Workers’ International, the SFIO.

Another imprisoned Commune militant was journalist Henri Rochefort, who would later become a supporter of ardent nationalist French general and politician Georges Boulanger, and who also took a public stand against the cause of French Jewish artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly accused of treason in an anti-Semitic smear campaign. Some of the Algerian insurgents were imprisoned with Rochefort on the island of Oléron, in western France while awaiting, like him, deportation to New Caledonia. He wrote of his discussions with them, and their fear about the lengthy sea voyage which they believed would be their last.

Rochefort, keenly patriotic and in support of French colonisation around the world, found his perceptions challenged by the discussions with the Algerians. “What they told me on the subject of the abuses and thefts which they constantly fell victim to distraught me with indignation and shame for our country,” he wrote. Rochefort struck up a friendship in jail with Ahmed ben Ali S’rir, a “young Moor” who he described an excellent draughts’ player, and who would die as a result of the dreadful prison conditions before his expected departure to the Pacific.

The deportations of the Communards to New Caledonia were carried out in successive waves between 1872 and 1878. Louise Michel and Henri Rochefort were placed aboard the vessel La Virginie in August 1873. The first boats to carry the Algerian rebels, placed aboard in cages, were La Loire and Le Calvados, which respectively arrived in the Pacific Ocean archipelago in October 1874 and January 1875.

'New Caledonia is a slaughterhouse for men'

A number of women were sent with the male Communards to New Caledonia either, like Louise Michel, as militants sentenced to deportation, or as wives who agreed to accompany their convicted husbands. In the first category were also Marie Cailleux, who had been accused of taking part in the murder in May 1871 of four clerics at the Paris square, place de la Roquette, and Nathalie Lemel, who was one of the organisers of the Commune’s “Womens’ Union for the Defence of Paris”. The arrival of the women was fiercely opposed by Father Montrouzier, the chaplain of the fortified prison camp on New Caledonia where some of the Commune veterans were placed, who denounced “the incompatibility of the presence of a priest in face of real prostitutes”.

Unlike the Commune militants, the deported Algerian rebels were not allowed to take their families with them to New Caledonia – the French government did not view them as having a settler's role to play in the archipelago’s colonial future. When the first of them arrived on the Loire in October 1874, they debarked at the harbour in Nouméa, the capital town situated on the main island, Grande Terre. Joannès Caton had been deported to New Caledonia for his part in attempting to establish a Commune in the town of Saint-Etienne in south-east France, and witnessed their arrival in his Journal d’un déporté de la Commune à l'île des Pins (Diary of a deportee of the Commune on Pine Island). Caton was at the time detained in a camp close to Nouméa, before he was later sent to an easier environment on one of the smallest islands in the archipelago, the Île des Pins.

“All of a sudden, the guards appeared at the bend,” he wrote. “They were followed by about 40 people in white robes; at first we thought they were the women of our comrades, but the uniformity of their dress announced that they were convent sisters […] Arriving at the prison, they were suddenly recognised and a single cry went out: the Arabs! They are the Arabs!”

While the group were the first Algerian “political” deportees, whose transportation organised under the terms of a March 23rd 1872 law established in France to deport the insurgents of the Commune, they were in fact not the first Algerians to be deported to New Caledonia. Before them were members of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh tribes in Algeria had in 1864, who led a rebellion against the French military conquest of the North African country when they briefly blocking the expansion of French occupation to the south before they were defeated in 1865. Some of those who took part in the revolt were sent, with common criminals, to hard labour camps in New Caledonia.

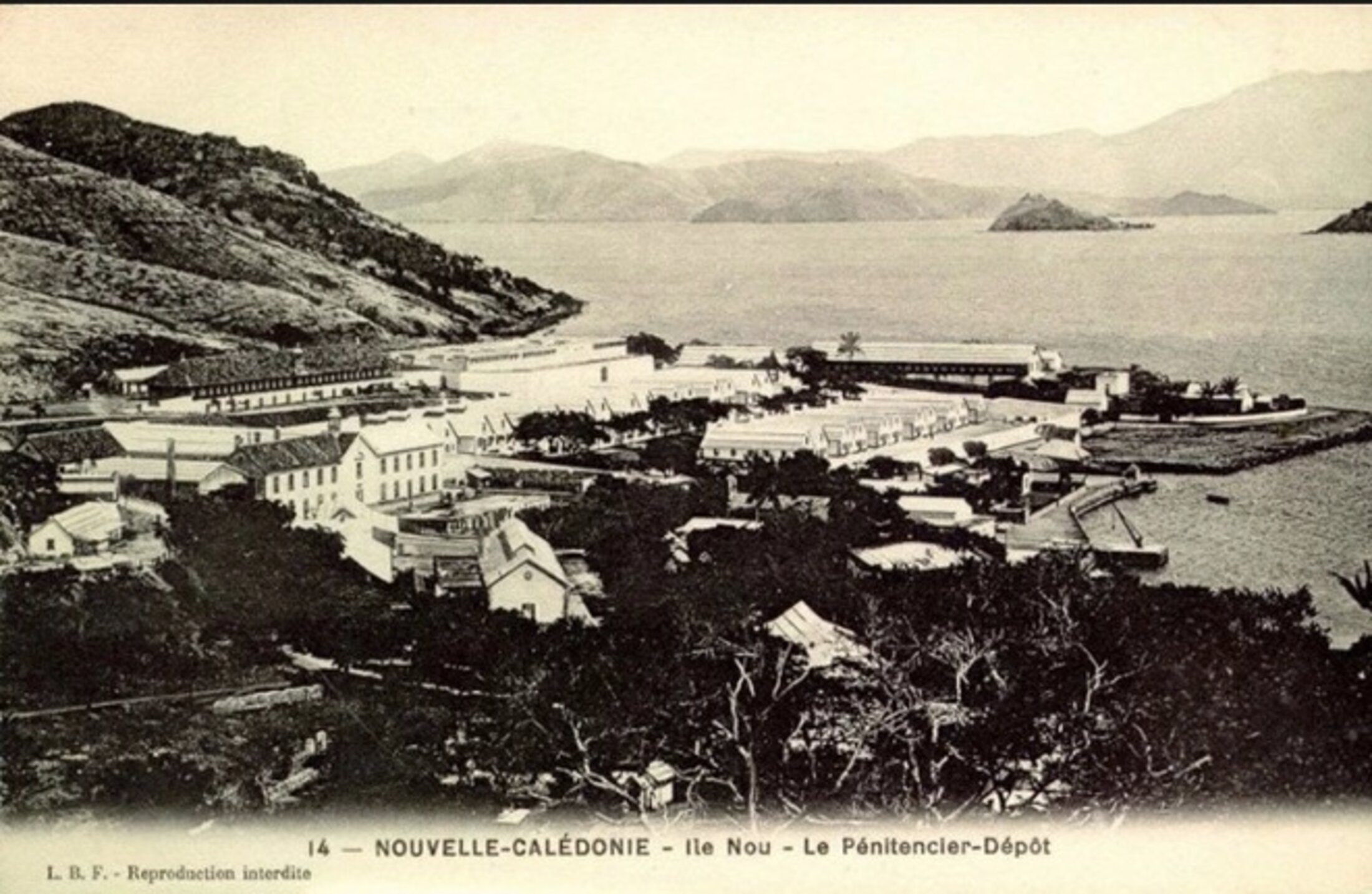

Meanwhile, some of the French deportees later wrote of their wonderment, on arriving in the South Pacific colony, at the beauty of landscape and vegetation, their awe heightened after a journey of several months in harsh conditions. But like the common criminals first sent to the archipelago ten years earlier, the reality of their lives was not be a life in a “tropical paradise” as it had been described by some French MPs who objected to their supposedly clement fate.

Many of the deportees were allocated to penal colonies on the Île Nou, beside Nouméa, on the nearby Ducos peninsula and on the Île des Pins, a small island to the south-east of Grande Terre. Those at the camp at Île Nou were submitted to notably tough conditions. One of them was Henry Bauër, who as a 20-year-old had taken an active part in the Commune, becoming an officer in the insurgent defence force and participating in the fierce fighting during “the Bloody Week” which ended in its defeat. Bauër was the illegitimate son of French novelist and playwright Alexandre Dumas père, whose works include The Count of Monte Christo and The Three Musketeers. Bauër, who became an author and journalist, detailed in numerous articles the hellish conditions of the penal colony, where he became close friends with Louise Michel with whom he regularly corresponded.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

It was the Communard deportees who would be the first to reveal the dreadful conditions and cruelty inmates were subjected to, a reality far from the picture presented in France when the first deportations were organised: what were called “transportations” were also described as a “humanist” move to offer convicts redemption, a new beginning and regeneration through the healthy force of work. But instead, inmates were shackled in balls and chains, sometimes chained together, tortured with thumbscrews, and humiliated with soup served up in shoes. In the centre of the camps were what were known as “the boulevard of crime”, where a guillotine was installed and punishments were delivered.

An anonymous letter written by one of the Communards and which somehow escaped being censored recounted: “New Caledonia is a slaughterhouse for men. It was put there, on the other side of the world, to protect your delicateness, so that you do not sense the smell of crime and that you do not hear the cudgel beating down on the heads of the captives.”

There were many skilled professionals among the Communards who were sentenced to hard labour, and they mostly came off better than the common criminals in the penal colonies because they were requisitioned for special jobs. Jean Allemane, for example, began his working life as a typographer and was sent to work in the government's local printshop. Gaston Da Costa, a young magistrate in the commune whose later death sentence was commuted to a life sentence of hard labour, was given a storekeeper’s job while mostly serving as a private teacher for the daughter of an accountant.

Most of them were assigned sooner or later to the Île des Pins, where they were allowed a large freedom of movement. Some of them, after a period of several years, were allowed to live in Nouméa.

As for the conditions of the Algerians during the early years of deportation, there remain hardly any direct records by them of their daily lives after landing in New Caledonia. The only indications are terse accounts by the military or those of the Communards – sometimes notes expressing fascination about them and often peppered with prejudices. Louis Barron, who was captured fighting with the Commune’s defence forces during “the Bloody Week”, and who later became a writer, was deported to the Île des Pins, where he was the editor of a journal called Le Parisien Illustré, which was one of several produced for the local community of Communard deportees. In September 1878 he wrote an article entitled, “Our neighbours, the Arabs” in which he stated: “The Arab in New Caledonia finds himself in his natural environment. The trees and the plants of this inter-tropical island are more or less the trees and plants of his country.” Barron wrote of how he was certain that “no longer having a horse” was “the biggest sorrow for the deported Arab” and that in face of the “the bitterness of captivity” having “a fatalistic religion softens their sufferings”.

Meanwhile, the deported Communards and the deported Algerians thought only of returning to their countries, and were watching for the slightest sign from Paris to allow it. An amnesty for the Communards would be pronounced in 1880, while the Algerians would receive their own only in 1895.

-------------------------

- This article is based on the French version here, and contains extracts from another in the series which can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse