Several short videos posted on Twitter on January 12th by supporters of the ‘yellow vest’ movement show CRS crowd-control police officers, deployed that day on the avenues that lead to the Arc de Triomphe in central Paris, armed with G36 assault rifles.

The military weapon, manufactured by German firm Heckler & Koch, has been issued to several special police units since the string of terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015, but is not a weapon destined for crowd-control operations like those during the January 12th yellow vest protests.

Questioned by French daily Libération, the Paris police prefecture confirmed that “several police services as well as the CRS were carrying HKG36 rifles” in Paris that Saturday as the yellow vest demonstrators arrived at their rallying points. “In the context of a terrorist threat that remains very high, the police services could not ignore this risk by carrying unsuitable equipment,” added the prefecture.

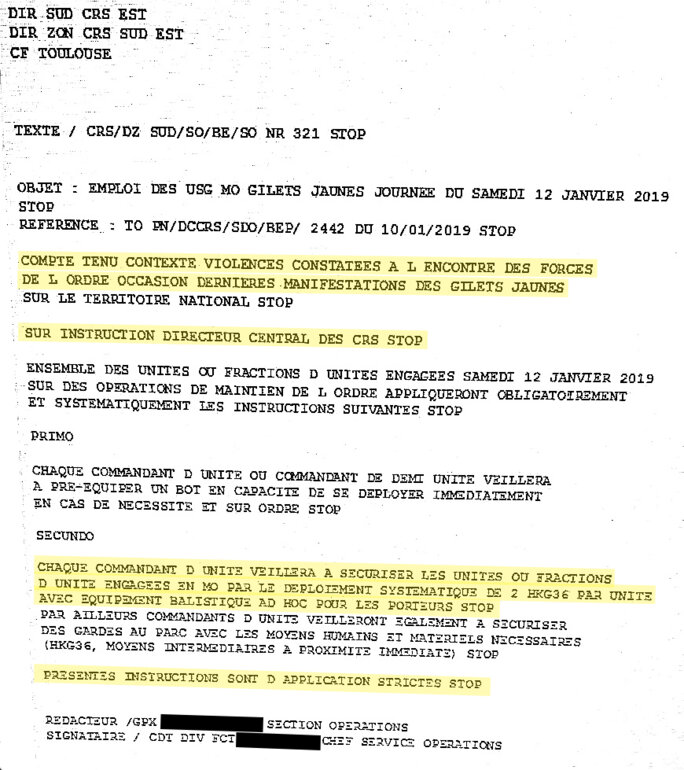

But according to a document obtained by Mediapart, the war weapons were explicitly deployed by the CRS central command “given the context of violence against the forces of law and order” during “the last yellow vest demonstrations in the country”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In a note sent to all of the regional CRS command units on January 10th, the national director of the CRS, Philippe Klayman, ordered all units engaged in crowd-control operations on January 12th to have, readied and equipped for action, an “observer-shooter” (a “binôme observateur tireur” in French, or “Bot”) “able to immediately be deployed in case of necessity and upon orders”.

“Each commander will ensure of securing the units engaged in MO [maintaining order] with the systematic deployment of 2 HKG 36 per unit with ad hoc ballistic equipment for the carriers,” Klayman wrote (see document immediately below). Contacted by Mediapart about the reasons for the deployment of such unusual weaponry in the context of the demonstrations, the French interior did not respond to our questions.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Klayman, a former reservist with France’s marine commando services, who was in charge of security for both of former French conservative president Jacques Chirac’s election campaigns in 1995 and 2002 (and who served in two ministerial cabinets under Chirac – those of then-interior minister Jean-Louis Debré from 1996-1997, and then-prime minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin, from 2002-2006), is known as an enthusiastic proponent for a more military-like organisation of the CRS.

In the backdrop to his move, interior minister Christophe Castaner, reacting to the continuing mobilisation of the yellow vests and the violent incidents that have marred their recurrent Saturday demonstrations, had already chosen to adopt a hardline policing strategy. This was illustrated by tactics that included the deployment in December of armoured gendarmerie vehicles in the neighbourhood of the Arc de Triomphe, and the engagement of “mobile” police units, which are in principal dedicated to carrying out arrests during disturbances, in crowd-dispersal operations. They do so armed with GLI-F4 “instant” stun grenades, which contain TNT, and weapons firing rubber bullets – Flash-Ball guns and the more powerful, increasingly used so-called “defence ball launchers”, or LBDs – which have caused numerous serious injuries to protestors and bystanders since the yellow vest demonstrations began in earnest on November 24th.

In early December, the French interior ministry announced that during the Saturday nationwide demonstrations on December 1st, a total of 1,193 rubber projectiles were fired by police, along with 1,040 crowd dispersal grenades and 339 GLI-F4 stun grenades. Since then, however, the ministry has halted the release of such statistics in public.

In an interview with French media outlet Brut on January 11th – the eve of the ninth successive yellow vest Saturday protests – interior minister Castaner warned: “Those who call for demonstrations tomorrow know that there will be violence and therefore have their share of responsibility.” He added that those taking part in the demonstrations at locations where “vandalism” is predicted would be regarded by him as “accomplices” in the events.

Castaner above all recognised his responsibility in the evolution of crowd control strategies in Paris compared to those of his predecessors. Previously, policing of demonstrations was largely static, but when pockets of violence erupted these would be surrounded and contained until they lost energy. The methods employed by the present government towards the yellow vest rallies include a more aggressive, broad confrontation with demonstrators, to disperse them and carry out arrests.

While Castaner last week claimed he had “never seen a policeman or gendarme attacking a protester”, he is now the target of a formal complaint lodged by Antoine Boudinet, a 26-year-old who lost his hand in the explosion of a GLI-F4 grenade during a demonstration in the south-west city of Bordeaux. The interior minister faces the possibility of further lawsuits from others seriously wounded by the grenades and LBD rubber bullet guns.

French daily Libération has estimated the number of yellow vest demonstrators who have suffered serious injuries caused by police weapons at 94, of which 69 were the result of LBD ammunition, and 14 of who lost the use of an eye. The toll of the past six weeks is already more than the total number of serious injuries caused by Flash-Ball and LBD ammunition recorded over the past ten years in France. The director-general of France’s national police force, Éric Morvan, revealed on January 11th that the police’s internal investigation service, the IGPN, which investigates alleged wrongdoing by police officers, has received 200 complaints from the public relating to incidents over the previous six weeks, and 78 cases had been referred to it by the public prosecution services.

Contacted by Mediapart, Jacques Toubon, the head of France’s official civil rights’ watchdog, “le Défenseur des droits”, said that his office was studying 25 complaints it had received, of which some included the joint complaints by groups of people, and that “among these complaints, 12 involve shots fired by defence ball launchers”.

Meanwhile, Toubon’s press office said “his position, regarding the current events, remains unchanged one year after the publication of his report on policing [street demonstrations] which underlined the evolutions of policing strategies and its dangers, and which underlined the difficulties relative to the training and use of intermediary weapons”.

That report, completed in December 2017, recommended “the prohibition of the use of defence ball launchers in operations of crowd policing”, and also that a study be launched into the use of so-called “intermediary weapons” which include the supposedly non-lethal LBD guns and GLI-F4 grenades used for crowd dispersal.

The toll so far of the injured in the yellow vest protests, and which is obviously provisional, illustrates the imprecisions of the police’s use of weaponry. On November 24th, five people were seriously wounded by LBDs, and three others by GLI-F4 grenades. On December 1st, 15 people were seriously wounded from LBD projectiles, and another three by the exploding grenades.

During the following week, five secondary school pupils were hit by rubber bullets during demonstrations close to their schools. On December 8th, 20 people were seriously wounded by rubber projectiles, of whom three lost an eye. On December 15th, three more individuals were seriously wounded, followed the next Saturday, December 29th, by another seven. On January 5th, six more people were seriously wounded by the weapons, and another ten on January 12th. An unknown number of others among or close to the demonstrations have been less seriously wounded by the use of Flash-balls and LBDs.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“It is a real problem,” said a senior civil servant, who has been involved in observing the Paris demonstrations, speaking on condition his name is withheld. “The police, above all the plain clothes branch, intervene with ‘intermediary weapons’ on a completely individual basis. There is no control over what they do.”

France’s national police force director-general, Éric Morvan, issued a notice to police units across the country on January 15th, as revealed by public broadcaster France 3, in which he called on officers on crowd control duties at the demonstrations to “rigorously ensure a respect for the operational conditions” for use of the LBD 40 rubber bullet launcher.

In December 2017, when Jacques Toubon’s report was published, Paris police chief Michel Delpuech wrote to Toubon announcing that he had “taken the decision to ban the use of the LBD 40 in crowd-control operations, given its dangerousness and its inappropriate nature in such contexts”. Delpuech banned use of the weapon by the police department in charge of maintaining public order in the capital, the DOPC, although he authorised its use by the department responsible for security in specific local situations in the Paris region (the DSPAP).

In 2013, two types of rubber bullet guns, or “launchers” as they are also called, were used by French security and police services. One was the LBD 40, manufactured by the Swiss firm Brügger & Thomet and commercialised under the name GL06, and the other was the Flash-Ball Superpro, made by French armoury firm Verney-Carron.

At the time, the police and gendarmerie were equipped with 3,215 Flash-Ball weapons, and 3,083 LBD 40s. Since then, the LBD 40s have overtaken the number of Flash-Balls, although the French interior ministry refuses to detail the exact numbers of each. Flash-Ball manufacturer Verney-Carron says that around 4,000 of its weapons are currently still in service with both the police and gendarmerie, and also the municipal police, which has more restrained powers.

Contacted by Mediapart, Karü Brügger, whose company makes the LBD gun, described the weapon as “ideal” for “police confronted with riots”, insisting that “technically, we are the best”.

He claimed that “our great advantage” is the simplicity in training officers to use the weapon. “In three minutes, you’ve done it, and the use is very simple,” he added. His firm, Brügger & Thomet, has recently won a contract to equip US border control guards with the weapon.

The Flash-Ball and the LBD differ in both their fire power and intended usage. “The range of the Flash-Ball doesn’t exceed ten metres,” said Fabien Jobard, a research director with the France’s CNRS scientific research body and a specialist in crowd control issues. “Its firepower is less strong, its shot is less precise, but it is a weapon destined to deal with situations of legitimate self-defence, or truly imminent threats. The LBD has a paradox, in that it compensates imprecision by a greater firepower, and at short distance it has a formidable power.”

The LBD officially has a range of between ten and 50 metres. It has a rifled cannon for accuracy and a sight called an “electronic target designator”, and comes under the classification of “first category” weapons, which refers to battle weapons – unlike the Flash-Ball. The projectiles used in the LBD are also different; whereas the Flash-Ball, which is also responsible for causing serious injuries, uses wholly rubber projectiles, the LDB ammunition is a projectile made up of two half-spheres of rubber attached to a plastic base.

Despite that, its Swiss manufacturer claims that the projectiles are “entirely safe even at close distance” and that “there is no penetration of the skin, no broken ribs nor internal injuries”. Which appears to be a clear untruth given the gravity of the injuries sustained during demonstrations. Indeed, the French interior ministry warns that there is a “risk of more important injuries at less than ten metres”.

Guillaume Verney, director of Flash-Ball manufacturer Verney-Carron, is unhappy that the weapon’s name, first patented in the 1990s, is used as a generic term for rubber projectile guns, including LBDs, especially in the context of the serious injuries they cause. “The Flash-Ball is above all not used for crowd policing,” he said. “In its usage guide, it has never been recommended for management of crowds. Indeed, the CRS were never equipped with Flash-Balls. The problem with firing into a crowd is that people move.”

The fact of that observation was underlined by Toubon in his December 2017 report. “During a demonstration, where by definition those people targeted are generally in groups and mobile, the point aimed at will not necessarily be the point that is hit, and the person targeted might not be the one who is hit,” wrote France’s defender of rights.

The instruction manual for the LBD notes that, while the weapon can be used “during a mob gathering”, “the person shooting must ensure that eventual third parties present are out of the field of fire” and take into account the mobility of the person targeted. It also states that it is necessary to give priority to targeting “the torso and the superior or lower limbs”, and that “the head is not targeted”.

But during the yellow vest protests over recent weeks, around 75% of those hit by LBD ammunition were struck in the head.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.