In their separate comments about two quite different cases, Emmanuel Macron and his principal political opponent, far-right figurehead Marine Le Pen, both attacked France’s justice system using the very same arguments, and sometimes the very same words.

What they agreed about was that the results of an election are more legitimate than the law, and that from obtaining electoral support comes the privilege of being exempt from the process of justice.

This anti-judicial populism, a sort of French Trumpism, is the result of a political and moral collapse that is not limited to one camp alone. It was illustrated on April 24th by Macron, speaking on the sidelines of a visit to Madagascar, in his comments to reporters.

He was asked about the suggestion that former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, 70, should now be stripped of his Légion d’honneur – France’s highest civil award for merit – after France’s highest appeals court last December upheld his conviction for corruption and influence peddling and the one-year jail sentence he was given (commuted to wearing an electronic tag, which was removed on May 14th after just a few months).

Under the French law governing the Légion d’honneur, Sarkozy should automatically be stripped of the award. But Macron voiced his disapproval of such a move. “Given that he was elected by the sovereign people […] I think he merits respect,” said Macron. “It is quite something to have been president of France. I’m not talking about a judicial decision. It is a question of respect. I think it is very important that former presidents be respected.”

One might add that it is also “quite something” to be convicted of corruption when one has held the office of president – it is even the first such conviction in French history.

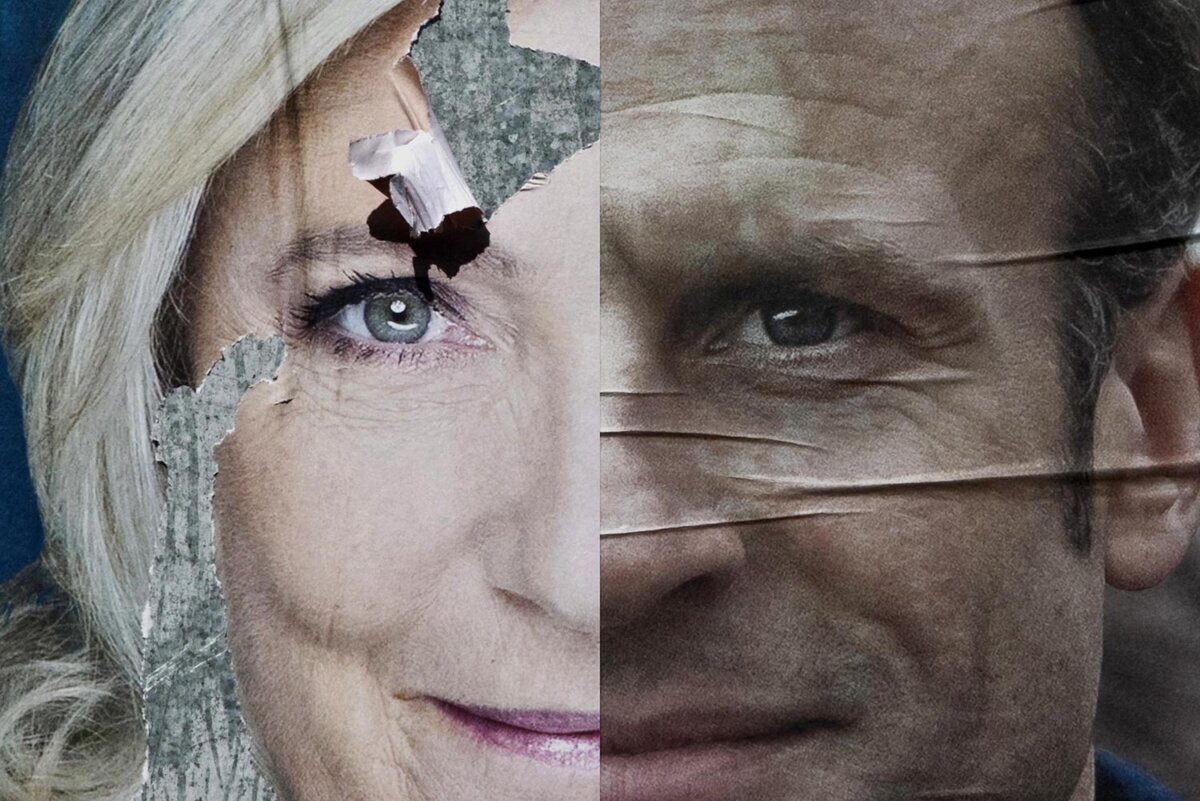

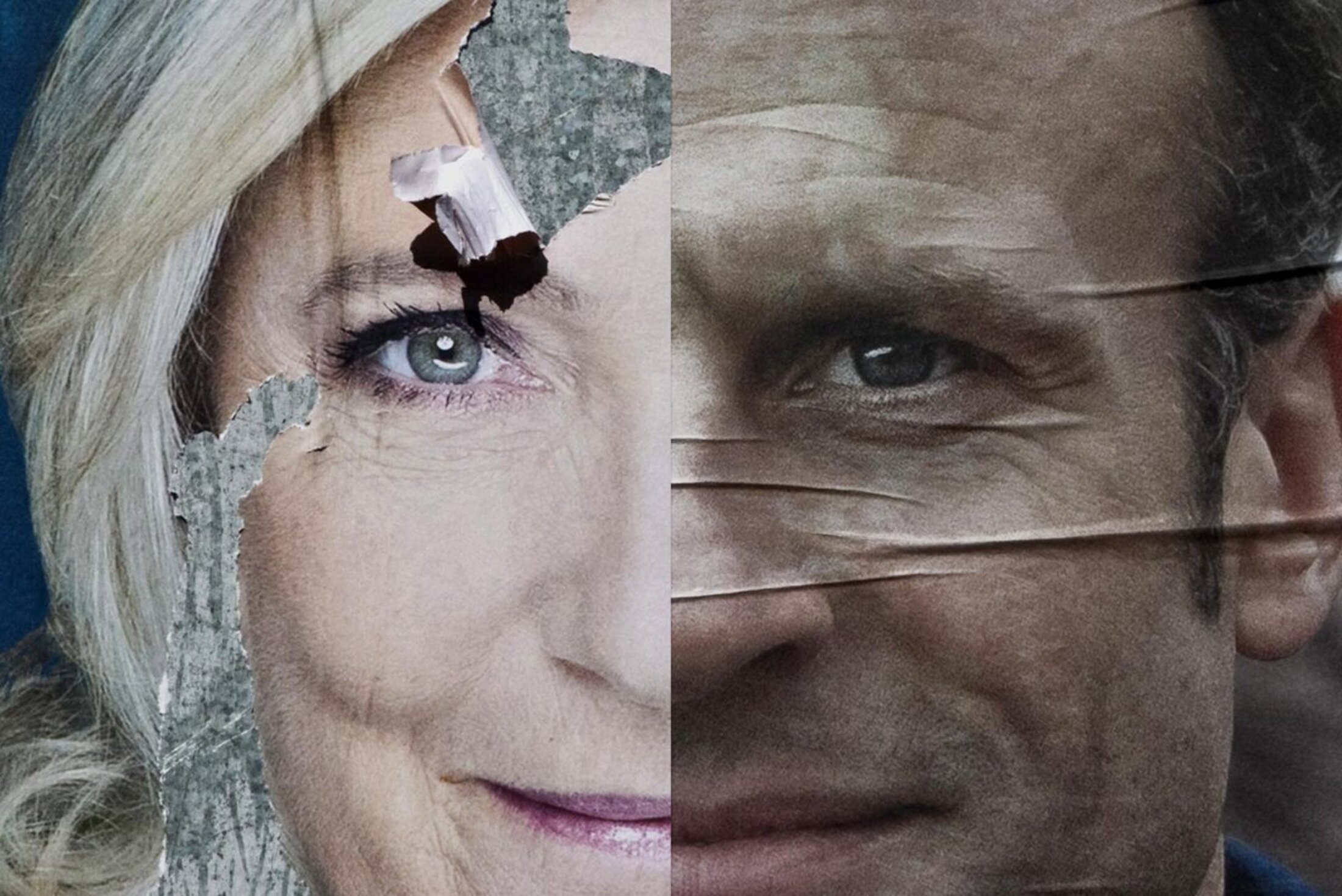

Enlargement : Illustration 1

On April 1st, three weeks before Macron made those comments, Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) group in parliament (and de facto leader of the party, the renamed Front National), addressed a group of RN parliamentarians when she similarly employed the term “the sovereign people” to attack the justice system over her own legal woes. The previous day Le Pen, 56, had been found guilty, along with other party members, of embezzling European Parliament funds. But it was the sentence that caused most hurt; along with four years in prison, two suspended, and a 100,000-euro fine, Le Pen was banned with immediate effect from holding public office.

That meant that she could not run, as planned, in the presidential elections in 2027 which, according to current opinion surveys, she could hope to win. “The system,” she announced, “has brought out the nuclear bomb. If it uses such a powerful weapon against us, it is obviously because we are on the point of winning the elections […] But who is sovereign in our country? Is it the people or the magistrates? It seems to me that it’s the people.”

Le Pen appealed the verdict, but under the usual judicial agenda her appeal was likely to be heard too late for the presidential campaign. In an exceptional move, announced the following day, the appeals court has pledged to rule on her case by the summer of next year, offering the far-right leader a political lifeline.

In the case of Nicolas Sarkozy, Macron’s comments outraged several recipients of the Légion d’honneur and others who are descendants of recipients. They commissioned lawyer Julien Bayou (a former Member of Parliament and national secretary of the Green party EELV) to submit a request before an administrative tribunal for Sarkozy to be stripped of the award.

Bayou, whose grandfather was awarded the Légion d’honneur, formally filed the request on May 6th. “Removing the Légion d’honneur does not weaken the office of president, it respects it,” declared Bayou. “When one tolerates that a former president, a convict, keeps the Légion despite the regulations, both the Légion d’honneur and the office of president are sullied.”

One of the applicants is Bernard Brun, a former senior management figure at French utility giant EDF, who was awarded the Légion d’honneur in 2010 under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy. He released a statement through his lawyer to say that despite his political support for Emmanuel Macron, “I cannot tolerate positions that are so contrary to the most elementary public and civic morals”, adding: “All that for what? For obscure reasons of petit politicking and to keep Mr Sarkozy in his little papers. It’s just not possible. I had thought of sending back my award, but in the end it’s rather for the Order [of the Légion d’honneur] to exclude Mr Sarkozy.”

In the case of the trial of Le Pen and other RN party members over the embezzlement of European Parliament funds estimated to total 4 million euros, centring on the wrongful payment of salaries as parliamentary assistants to RN staff and who in reality worked only for the party, the appeal by Le Pen and her co-accused will be heard in the first half of 2026. In its ensuing judgement, the court will decide whether, in the case it finds the defendants guilty, the sentence should again include a ban on Le Pen from holding public office, and whether that should be given immediate effect.

Democracy is not about elections alone

While awaiting a legal decision – administrative in the case of Sarkozy and under criminal law in the case of Le Pen – the championing by two of France’s prominent political figures of the notion of “popular sovereignty” to override a judicial decision should sound the alarm over the debasement of public debate. It concerns one of the fundamental pillars of democracy, namely that everyone is equal before the law.

There is a cartel with a culture of impunity at work now, and they don’t hide it. The argument employed by both Macron and Le Pen, but also by other politicians (who include the radical-left La France Insoumise party leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon, current prime minister François Bayrou, and the former conservative party leader turned far-right ally Éric Ciotti), is worth studying closer.

Because to see elections as the alpha and omega of democratic functioning, a totem of immunity that can be used against those who are not elected politicians, is one of the most dangerous formulas within the various definitions of populism.

In a small book that is published under the provocative title of Against elections: The case for democracy (published in the UK by The Bodley Head), Belgian historian David Van Reybrouck, who gained worldwide recognition for his work on the colonial history of the Congo (Congo: The Epic History of a People), warned: “We have reduced democracy to a representative democracy, and representative democracy to elections. A valid system thus found itself confronted with serious problems. For the first time since the American and French Revolutions, the next elections weigh more than the previous ones. This is about an astounding transformation. The urns now allow only a very provisional mandate. We are rowing with oars that are forever getting shorter. Democracy is fragile, more fragile than it ever was since the second World War. If we are not careful, it will degenerate little by little into a dictatorship of elections.”

Van Reybrouck ends his stimulating book by voicing concern about the corruption that gangrenes numerous democratic countries around the world, and the sentiment of disgust that it causes among citizens. It is urgent to “democratize democracy” he concludes.

It is also the sense of a 2015 book of reference by French historian and sociologist Pierre Rosanvallon entitled Le Bon Gouvernement. This former lecturer with the prestigious Collège de France underlined “the illiberal potentiality of [French] presidentialism”. We are in the thick of that, and the recurrent scandals in France over the years appear like a laboratory study of the catastrophe.

Rosanvallon argues in his book that the legitimising of democracy simply by the urns, in the name of expressing a “general will” of a nation is a “fiction” that one must not give in to. “As a procedure, the arithmetic dimension of the majority principle is easily stamped on minds, for everyone can agree on the fact that 51 is greater than 49, and its adoption allows for, in an unquestionable manner, the imposition of a choice.”

“But in sociological terms,” he adds, “one cannot say that the majority express [the will] of all the people; it expresses but a fraction of the latter, even if it is dominant […] It is upon this fiction that the performance of the democratic election is founded.” Rosanvallon concludes that it is precisely that fiction “which has led to considering the legitimacy of a [governing] power that was consecrated in this manner to be limited”.

The lessons of history

In other words, democracy is not only about the vote. The legitimacy offered by the vote, which is of course always preferable to the winning of power by force or by trickery, does not validate all the actions of those elected. Quite the contrary. The centuries-long existence of France’s republic has taught us that the first debt that the governing powers have is that of responsibility.

To scorn all the driving forces in a democracy – which for example include, unions, associations, journalists and magistrates – in the name of electoral legitimacy is the stuff of armchair autocrats.

What the justice system has in particular is that it represents the institution that traces a line between what the law allows and does not allow, and the fact is that laws are voted in place by those who are elected.

To want to hide from a judge is the behaviour of criminals. But to argue in favour of it in the name of an electoral victory – as Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen have done in cases where the facts have been perfectly demonstrated, the rights of the defence respected and the trial fair – amounts to no less than championing a form of anti-democratic absolutism, but in the name of democracy. Welcome to a plot from George Orwell.

When the crowd look at the wealthy with eyes like those, it is not thoughts that are in the mind, it is events

There where France’s republic is a combination of fundamental freedoms and the necessary limits to preserve them, some are imposing upon public debate the idea of an aristocracy of elected representatives, who should supposedly be less submitted to common laws than others. That reasoning could become the breeding ground for the worst. During the 1852-1870 Second Empire in France, Napoleon 3rd (1808-1873) justified limiting the freedom of the press because, he argued, the press only expressed the personal ideas of journalists, as if the governing powers were elected.

It is no accident that Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen and others target the anti-corruption services of the justice system, which attack the crimes of their political milieu, where power, money and interests corrode the ones and the others. But they see no problem with the strict application of the law for any other form of delinquency.

Those with an understanding of French history know that a mixture of an economic crisis and outrage at corruption can prompt revolutions. In 1847, when France was shaken by the Teste-Cubières scandal, centred on a case of bribery and illicit profit involving a minister for public works, the novelist, poet, essayist and politician Victor Hugo, author of Les Miserables, warned: “When the crowd look at the wealthy with eyes like those, it is not thoughts that are in the mind, it is events.” He was of course right. One year later, a popular uprising in Paris saw the July Monarchy fall in just three days, leading to the creation of the Second Republic.

In 2017, a man who properly recognised the urgent need to moralise French public life addressed an enthusiastic crowd: “Justice is at the heart of the project that is ours,” he said, “because indecency, privileges, have lasted too long and we want the same rules for everyone. Whatever the statutes, we want responsible, exemplary leaders who account for themselves.”

The man was Emmanuel Macron. But that was before.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this op-ed article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse