On Sunday June 26th the voters of the Loire-Atlantique département or county in west France – where some 967,500 people are on the electoral roll – were asked to say yes or no to plans for a new airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes. It was the first time in France that citizens have been able to vote in this way on an infrastructure project that affects the environment, plans that have already been declared a public utility by the state. The outcome was a victory for backers of the scheme, with 55.17 % of people who voted supporting the building of the new airport.

However, this historic consultation process certainly had some shortcomings and in-built bias. For one thing, the area from which voters could take part in the referendum was too restricted, and did not give a say to inhabitants in nearby local authorities who must also help pay for the new airport. The question people voted on, “Are you in favour of the plan to transfer Nantes Atlantic Airport [editor's note, the existing airport just outside the city of Nantes] to the commune of Notre-Dame-des-Landes?”, was too simplistic and provided no alternative. In addition the information given to the public was insufficient, for example on how much abandoning the project would cost, and there are serious questions over how the state can claim that it would cost more to improve the existing airport than build a new one.

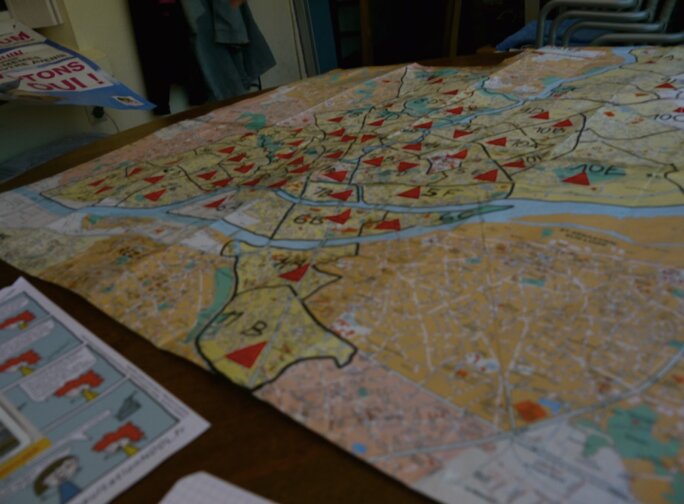

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Yet this referendum – which has no binding authority, even though the state said it will abide by the outcome – is more important than the scant national coverage it has received would suggest. In reality what was at stake in this vote was not local at all: the issue is not just about an airport and was not restricted simply to one environmental question. It is a battle over what represents the general interest.

For the referendum posed a question that is both fundamental and completely absent from the the traditional world of politics: what relationship are we building with our environment? Does living on a particular plot of land mean yielding to the rules of economic utility or respecting its natural functions such as the free circulation of water, the species who live there, the absorption of carbon dioxide, the resilience of the soil faced with the risk of floods and so on? What air do we want to breath, what water do we want to drink? When will we stop looking at grasslands, forests and fields as empty spaces of no value?

Each year development for commercial projects, transport infrastructure and housing destroys between 50,000 and 100,000 hectares of land and agricultural areas in France. Artificial surfaces, that is to say ground which has lost its natural state, now cover 9.3% of mainland France. They have increased in area by nearly 70% in 30 years, which is much faster than the rise in population. The equivalent of a département or county disappears under concrete every ten years. More than one half of the land devoured is used for individual homes.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

This destruction of our land is also a climate bomb. The concreting of French land emits 100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. That represents a fifth of all the country's carbon dioxide emissions. It is huge. It is almost as much as all the annual emissions that come from transport in France. The movement to stop the airport from being built at Notre-Dame-des-Landes is perhaps one of the first genuine social movements against climate disruption in our country, after the mobilisation against shale gas. It raises the alarm about the catastrophe represented by the irreversible destruction of land that has been protected for 40 years from the impacts of intensive farming.

Who decides on land use, and what interests does it serve? The local prefects or state officials are both the decisive decision makers on the development of local areas and the representatives of state support for these projects. They both sign off on the consultative opinions of the environmental authorities and deliver the authorisations to carry out the work. The state is judge and jury in the Notre-Dame-des-Landes project and has been clearly caught acting in collusion over the affair. For example, Bernard Hagelsteen, the former prefect for the Loire-Atlantique and for the Loire region from 2007 to 2009, today works for the huge French construction firm planning to build the new airport, Vinci. Loïc Rocard, who is today advisor to prime minister Manuel Valls on energy and transport issues, worked for Vinci in charge of its high-speed railway projects. Nicolas Notebaert, a directer at Vinci Concessions, recently promoted to Vinci's executive committee, was a member of the private office of Jean-Claude Gayssot, the communist minister under the 1997-2002 Lionel Jospin government who relaunched the Notre-Dame-des-Landes project, one that has been under discussion now for some 50 years.

According to André Vallini, the current junior minister for local government reform, “for France to remain France, we have to continue building airports, dams, motorways, high-speed railway lines, tourism infrastructure”. This government confuses the interests of the large construction firms with that of national identity.

But this decision-making decision dates from another age. At a time of climate disruption, any new major source of greenhouse gas heats the planet that belongs to us all. One can no longer aim at influencing a particular region without it having a connection with the rest of the world. The devastation of the climate, the impoverishment of biodiversity, the massive polluting of soil and water has forced a rethink on society's needs. For the local councils in the Pays de la Loire region, their area has more need of a new airport than 1,600 hectares of wetland. But for the dozens of pilots, architects, accountants, naturalists, historians and farmers who have contributed to an incredibly full second opinion, it is the opposite decision that corresponds to the reality of the current world. They have scarcely been taken seriously by the decision makers, who for their part have not made all their calculation methods public. Officialdom claims to have a monopoly on the legitimacy of expert assessments. That is deeply debatable and is an attack on the workings of democracy.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The battle against the airport has created a radical and rural dream world, represented by the cabins perched in the tops of trees in the proposed development area or 'ZAD' that the authorities have wanted to pull down with diggers since 2009. This new world is “Against the airport and its world” but above all it stands for something else: life in the countryside far from the rush towards profits and the hell of the jobs market, with no leader, no rent to fork out, but instead people living together, sharing their means and their know-how.

When the occupiers of the site rechristened it an “area of definitive independence” it was partly a pious wish but partly, too, a reality. They have come to the fields and forests to live there for a few months or few years. The “illegal constructions” that the local prefect wants to destroy are not mere fortifications. There are bedrooms, a kitchen, a meeting room, a bar, a hospital, a radio studio. People mix together there every day, working, arguing, discovering, appreciating and helping each other.

“You don't prepare for the future by building huts,” the former socialist president of the Pays de la Loire region and strong backer of the airport project Jacques Auxiette said in 2012. Yet in many people's eyes a laboratory of ideas of the Left is taking shape amid the bustle of Europe's biggest open-air squat. What outlook for emancipation in a world without growth where the majority of politicians, even progressives, seem so dependent on the financial markets? What about the devaluing of materialism and consumerism, independence, the idea of doing things yourself, the slowing down of the pace of life? Or the role of deliberate democracy and direct action? The refusal to have a relationship with authority, the importance of hospitality and friendliness? For example, there is the depersonalisation of power, even symbolic, of the spokespeople for the site occupiers, who all choose to be called “Camille”, a transgender name.

For all these reasons the battle for or against the airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes goes beyond the local scale and the technical case for the project. It concerns us all, all citizens who want action on political issues towards a society where the particular needs of some do not count for more than the protection of all our interests.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be read here.

English version by Michael Streeter