It is a project of staggering expense. A new road on the French Indian Ocean island of Réunion linking two towns just 12 kilometres apart is set to cost at least 1.6 billion euros. That works out as around 130 million euros per kilometre of road, compared with the standard cost of building a motorway which is about 2 million euros per kilometre. But the reason for the huge discrepancy in price is simple: this new road is being built not on the land but on the ocean.

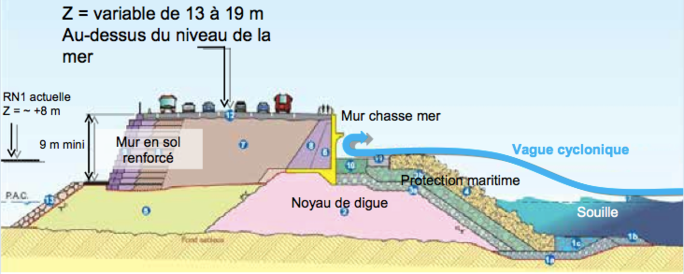

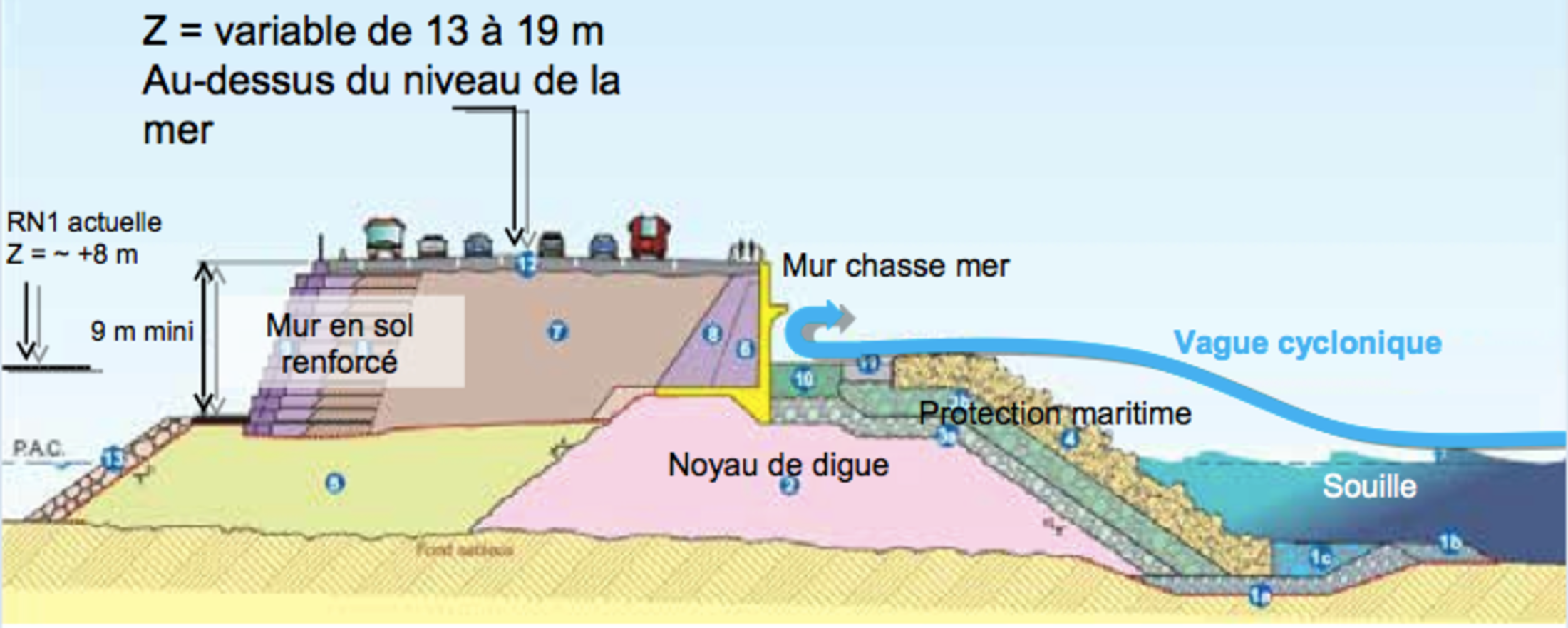

The so-called nouvelle route du littoral (NRL) road between Réunion's capital Saint-Denis and the small town of La Possession is designed to replace the existing busy but dangerous route that passes along the bottom of the island's cliffs. The aim is to avoid the dangers of regular rockfalls by building much of the new road on a massive viaduct just off the island's shore, with the rest of the highway being built on huge seawalls or dykes. However, the scale and design of the project, which is due to be completed in 2020, does not come cheap; hence the price tag which puts it on a par with some of the biggest construction projects in Europe, alongside the building of high-speed railways in France and motorways in Greece.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Apart from the massive headline cost, the project, which was awarded to major public works firms Bouygues and Vinci two years ago, is already beset by a number of problems. Last year a preliminary legal investigation was opened by the prosecution authorities in Saint-Denis into possible “corruption” and “favouritism” in relation to the scheme. As a sign of the potential seriousness of the affair, in April 2015 the investigation was handed over to France's new financial prosecution authority, which deals with the most sensitive probes into political-financial affairs.

The initial enquiries made by detectives from the gendarmerie in Saint-Denis have focussed on the award of all the public contracts involved with the road construction. Detectives have searched the headquarters of the Réunion regional council authority on the island and interviewed the council's president, Didier Robert, of the right-wing Les Républicains, who has strongly supported the building project since he was elected in 2010. Dominique Fournel, the councillor in charge of overseeing the scheme, has also been interviewed.

According to Mediapart's information, the financial prosecution unit is investigating to see if any commissions were paid to the entourage of councillors involved in the signing of contracts. In particular investigators are examining a suspect flow of money towards countries known for their opacity in financial matters, in particular the Seychelles. This archipelago, one of the largest tax havens in the Indian Ocean, is on a European Union black list of the “top 30 non-co-operative jurisdictions” when it comes to financial transparency.

Just weeks away from December's regional elections in France, the affair certainly looks set to be politically embarrassing for council chairman Didier Robert. Veteran opposition politician and communist senator Paul Vergès, 87, describes it as “Réunion's biggest political-financial scandal”. Robert, however, has said he will sue his political opponent for defamation and has threatened to do the same with any media outlet that reports his accusations. The council's executive has also sought to downplay the legal probe into the project. “The investigations carried out up to now are concerned solely with a framework agreement on the supply of materials,” says a council spokesman.

On top of the suspicions of corruption, the justice system is also examining whether the contracts were awarded according to the strict rules on public contracts, and in particular the workings of the council's tenders committee in October 2013. “I have never seen a committee held in such circumstances,” says Yasmina Penchbaya, a regional councillor for the opposition Alliance party, who was present at the vote for the two largest contracts. “I only had access for a handful of minutes to the documents, a huge tome of several hundred pages,” she says. “When I asked [someone] why we had not been sent the documents earlier, he told me 'it's confidential'. Thereafter, no member of the opposition was able to have access to the tender documents.” Nor, indeed, to the analytical reports either. This is despite the fact that the official rules on public contracts make it obligatory for such documents to be made public.

The council itself denies it impeded access to the documents. “All the reports as well as all the procedural documents were made available to be consulted by elected representatives, at the Department of legal affairs and contracts, and were done so well in advance of the meeting. On a broader level, the councillors were included in the major steps of the analysis of the bids.”

But opposition councillors are not the only ones to have complained about anomalies in the bidding procedure. The public works group Eiffage, the unlucky firm who lost out to the Vinci-Bouygues bids, has lodged several appeals before the administrative courts. Having failed to win an injunction, the company is now taking action on the substantive issues involved. Eiffage's appeal, a copy of which has been obtained by Mediapart, criticises the way in which the different sections of the proposed scheme were divided up, the very short time given to examining bids and the lack of reasons given for rejecting the unsuccessful ones. Finally, Eiffage states that some letters from the council seemed to have been “written in advance”.

However, this appeal will not be heard for at least a year, well after December's elections. If Didier Robert is re-elected as chairman of the regional council he is expected to maintain his full backing for the project, work on which has already begun.

Rocks pose serious threat to the environment

The regional council's stated aim for the road project is to make safe a route that is as economically important for the island as it is currently dangerous for motorists. The existing road, which is at the foot of a cliff that juts out into the ocean, is regularly hit by falling rocks, which has led to several victims over the last ten years. The new road will instead be built on the ocean itself, both on a viaduct and a seawall, requiring a great deal of construction work and huge quantities of rocks.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

This is where the other main problem with the project arises: its impact on the environment. “For cost reasons the region discarded the possibility of a road entirely on a viaduct, which would have had fewer environmental consequences,” explains Jean-Pierre Marchau, a town councillor for the green alliance Europe Écologie-Les Verts (EELV) in Saint-Denis. “Now, to build the two seawall sections will require 18 million tons of rocks. From the start, the environmental authority, which is part of the environment ministry, warned the region's president that the supply of rocks would pose a problem.”

In fact the issue of the rocks is dogging the whole project. For the region approved the scheme without knowing where it would find them. Having changed its mind several times the island's regional executive has recently decided that the rocks will be imported from the neighbouring island of Madagascar. This is despite the unfavourable verdict given by the nature protection council, the Conseil National de Protection de la Nature, which in a report commissioned by the ministry of the environment said that “in any case this would have been the option to prohibit, in particular because of the major risk of introducing invasive exotic spaces”.

The regional executive is also trying to exploit quarries in the west of Réunion itself. But this would involve digging out millions of tons of rocks in areas close to areas of habitation, in zones classified as sensitive in terms of biodiversity. Opponents of these plans – mostly local residents associations – criticise the “900 lorries day and night, the dust and nuisance” that they say would result and which would disrupt normal life.

Moreover, it seems impossible that enough rocks can be extracted from Réunion alone for the massive construction project. “The requests to exploit a quarry will be examined case by case,” says the prefecture – the local state representative body – which handles quarrying permits. The process will be slowed even further by appeals against changes to the local quarries plan which are currently being heard in the administrative court at Saint-Denis and at the Conseil d'État, the highest administrative court in France.

The rocks are just one problem as far as environmental opponents are concerned, for they consider the entire 1.6 billion euro road project is bad for the environment. “This plan for a new coastal road is part of the car culture, an approach that is catastrophic for La Réunion which needs a different approach altogether,” says Pascale David, the local representative of the alternative transport users' association ATR-Fnaut.

Ironically, the new road will be financed with public money that had originally been earmarked for the construction of a projected tram-train public transport system. However that project, backed by most opposition politicians on the island, was scrapped by Didier Robert in 2010 with the blessing of the central government in Paris. Just a few months after Robert came into office a protocol was signed with the prime minister's office guaranteeing the transfer of the tram-train funds to the new road plan. This involved 515 million euros from the European Union and 532 million from the French state, with the rest of the money coming from the region.

However, the regional executive authority has taken a major financial risk in abandoning the railway scheme. In a report in 2012 the regional watchdog authority, the Chambre régionale des comptes, forecast a “major financial slippage” in the event that the firms who had won the contract for the abandoned tram-train project brought successful legal action. And that is precisely what could occur, with legal action over the scrapped scheme currently before the administrative court of appeal in Bordeaux.

A final absurdity of this whole affair is that the litigant in that case in Bordeaux is none other than Bouygues. In other words, the same construction company that, along with Vinci, was awarded the 1.6 billion euro road project is also claiming 169 million euros from the regional authority on Réunion for having abandoned the railway project, for which Bouygues had also been a contractor. The claim is for “losses arising from from the carrying out of numerous studies and the use of numerous architects”, says the giant construction firm.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter