Emmanuel Macron's strategy came back to haunt him. By reducing the political debate simply to his opposition to nationalism, the president allowed that very force to become the only opponent capable of beating him at the European elections held on Sunday May 26th. Meanwhile the Left and the mainstream Republican Right were divided and fragmented.

The official turnout was 50.12%, a significant increase on previous European elections. Marine Le Pen's Rassemblement National (RN) – the former Front National – finished top with 23.3% of the vote, just ahead of President Macron's ruling La République en Marche (LREM) on 22.41%. In third place were the green movement Europe Écologie-Les Verts (EELV) on 13.47% of the vote, well ahead of the conservative Les Républicans – the party of former president Nicolas Sarkozy – on 8.48%. All the other party groups on the Left were well under the 10% level, with radical left La France Insoumise ('France Unbowed') or LFI on 6.31% and the Socialist Party (PS) just a fraction behind on 6.19%. The list headed by former socialist presidential candidate Benoît Hamon received 3.37% of votes while the French Communist party (PCF) were on 2.49%. The list headed by nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, meanwhile, received just 3.51% of the vote.

A defeat for Emmanuel Macron

The communications spin from the Élysée cannot hide the truth. Though the president's party limited the damage by more or less preserving the electoral base he achieved in the first round of the presidential election in 2017 (24%), and while LREM came within a percentage point of Le Pen's RN and was well ahead of all the other parties, this result is a defeat for Emmanuel Macron. LREM had hoped to come first but ended up in second place.

“When you finish second in an election you can't say you've won,” prime minister Édouard Philippe noted after the results. A few minutes earlier a joyful Marine Le Pen had called for the dissolution of France's second chamber the National Assembly.

The setback for the ruling party is all the greater given that, at just over 50%, turnout was up. It was not only around ten points higher than predicted by polling companies, it was also much higher than seen in previous European elections (41% in 2009 and 42% in 2014).

The increased level of voter participation was surprising after an election campaign noted for its dismal nature. It showed itself incapable of tackling key issues of public interest such as the democratic future of the European Union, the neo-liberal shackles imposed by the EU's treaties and the need for environmental and energy transition. The campaign was particularly depressing for voters on the Left, unhappy at the divisions in their own camp faced with the developing duel between the centrist LREM and the far-right RN.

A detailed analysis of the votes based on the regions, ages and socio-professional background of the voters may show otherwise, but at first glance it appears that the increased turnout shows that the call to punish Emmanuel Macron at the ballot box – which originated on the far right but also came from La France Insoumise and the 'yellow vest' protestors – worked. The beneficiary of this appeal was Marine Le Pen's RN. Usually a rise in turnout in France helps other political groups in their appeal to voters to keep out the far right.

Another sign of the weakness of Emmanuel Macron's vote in this election is the fact that it is lower than his party's performance at the 2017 Parliamentary elections, in which the turnout at 49% in the first round was comparable to these European elections. At the time LREM scored 28% of the vote, a figure which rises to 32% if you include its electoral allies, the centrist MoDem party.

The shattering of France's political landscape

However, though this election can be seen as the electorate punishing the president, the result does not undermine his broader strategy: which is to shatter for good the French political landscape which has lasted for more than 40 years.

In Sunday's vote the LREM and RN were far ahead of their nearest rivals, with Yannick Jadot's green list in a distant third spot on 13.47%. So from this point of view the 'polarisation' between the two political groups – which Macron wants so he can contrast his progressive approach with that of the nationalists, and which Le Pen wants so she can highlight her nationalism against the cheerleaders of globalisation – has become established.

The president of the Republic must bear clear responsibility for the success of the far right in this election, given that Marine Le Pen had been extremely weakened by her poor showing in the second round of the presidential election back in 2017. It is down to his policies, his political strategy and his choice of election campaign.

In contrast, the two parties who had dominated French politics up to 2017 once again confirmed that these movements lie in ruins. The Socialist Party (PS), which had scored just 6% in the last presidential election, was simply relieved that it had polled higher than 5% in Sunday's election; meanwhile the conservative Les Républicains (LR) have plunged to 8.48% of the vote share, raising question marks over the survival of their leader Laurent Wauquiez.

LR had hoped to pick up votes and poll over 10% thanks to their young and ultra-conservative candidate François-Xavier Bellamy. The party's worst score up to now was the 12.8% achieved under Nicolas Sarkozy in 1999.

“LR has been carved up by Emmanuel Macron and the RN,” the historian and specialist on the far-right Nicolas Lebourg told Mediapart's election night broadcast. “Laurent Wauquiez has never decided on Les Républicains' political identity,” he said. “The National Front-lite stance is a complete failure,” he said. And as the “liberal centre is occupied, all the Right's [political] stances are occupied by parties other than the party of the Right.” Nicolas Lebourg said that the LR also suffered from its leader's “catastrophic” image, saying he constantly gave the impression of a “lack of sincerity”.

The green surprise

Faced with the domination of RN and LREM, the only other group to have emerged with a strong performance was the green EELV, despite what many saw as a lacklustre campaign. They appear to have benefited from the higher turnout.

“The turnout confounded some of the poll estimates,” the head of the EELV list, Yannick Jadot, said on Sunday evening. “I'm very happy that young people in particular turned out for this vote.” According to some early data it seems as if the EELV picked up more votes from people aged under 34 than anyone else. The strong showing of the EELV confirms a trend seen in much of the rest of Europe - the greens came second in Germany - as part of a wider mobilisation against climate change.

Other parties on the French Left also sought to highlight their green credentials, something which had not happened before in a European election. Most striking in this respect was that of the Socialist Party list led by essayist, director and journalist Raphaël Glucksmann, whose members included the well-known environmental activist Claire Nouvian.

Other environmental groups also achieved some notable scores in this election, for example the Animalist Party which got 2.17% of the vote. This compares, for example, with the 2.49% achieved by the French Communist Party list led by Ian Brossat even though he had a great deal of media exposure and has a widespread network of activists on the ground. Not far behind was the Ecology Crisis list led by Dominique Bourg which attracted 1.82%, rather more than Lutte Ouvrière ('Workers' Struggle') which was on 0.78%.

For EELV, Sunday's result is a significant success. After the presidency of François Hollande it had been written off as dead electorally and had been riven by divisions and defections. These had continued until the last minute with two former EELV elected representatives, Pascal Canfin and Pascal Durand, having joined the ruling LREM list led by former Europe minister Nathalie Loiseau.

This success will also boost those who believe that the environmental movement should follow its own path. Yannick Jadot spent the election campaign restating his desire for the movement to stay clear of the Left/Right divide and to set out a distinctive green approach and pick up voters on the Left disappointed by Macron's presidency. The score achieved by Jadot's list is close to the best ever result by the EELV in a European election, which was 16.9% in 2009. “The decision – attacked by some on the Left – of the EELV to build an autonomous environmental [movement] rather than try to 'reconstruct the Left' paid off,” says political specialist Vanessa Jérome.

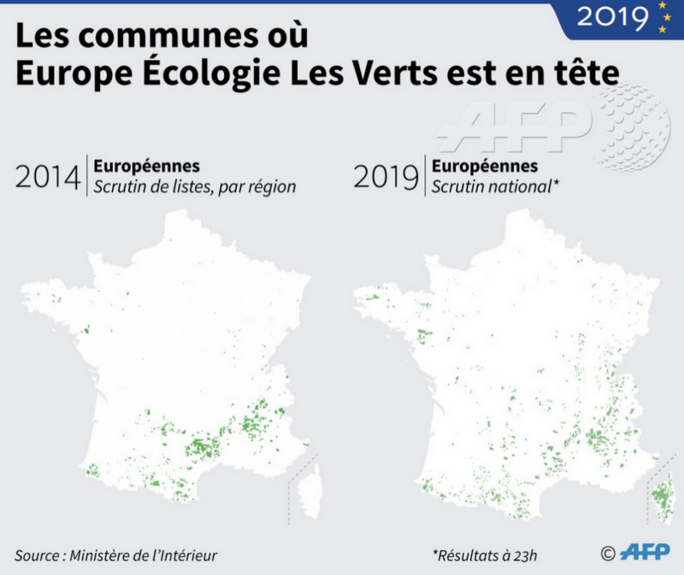

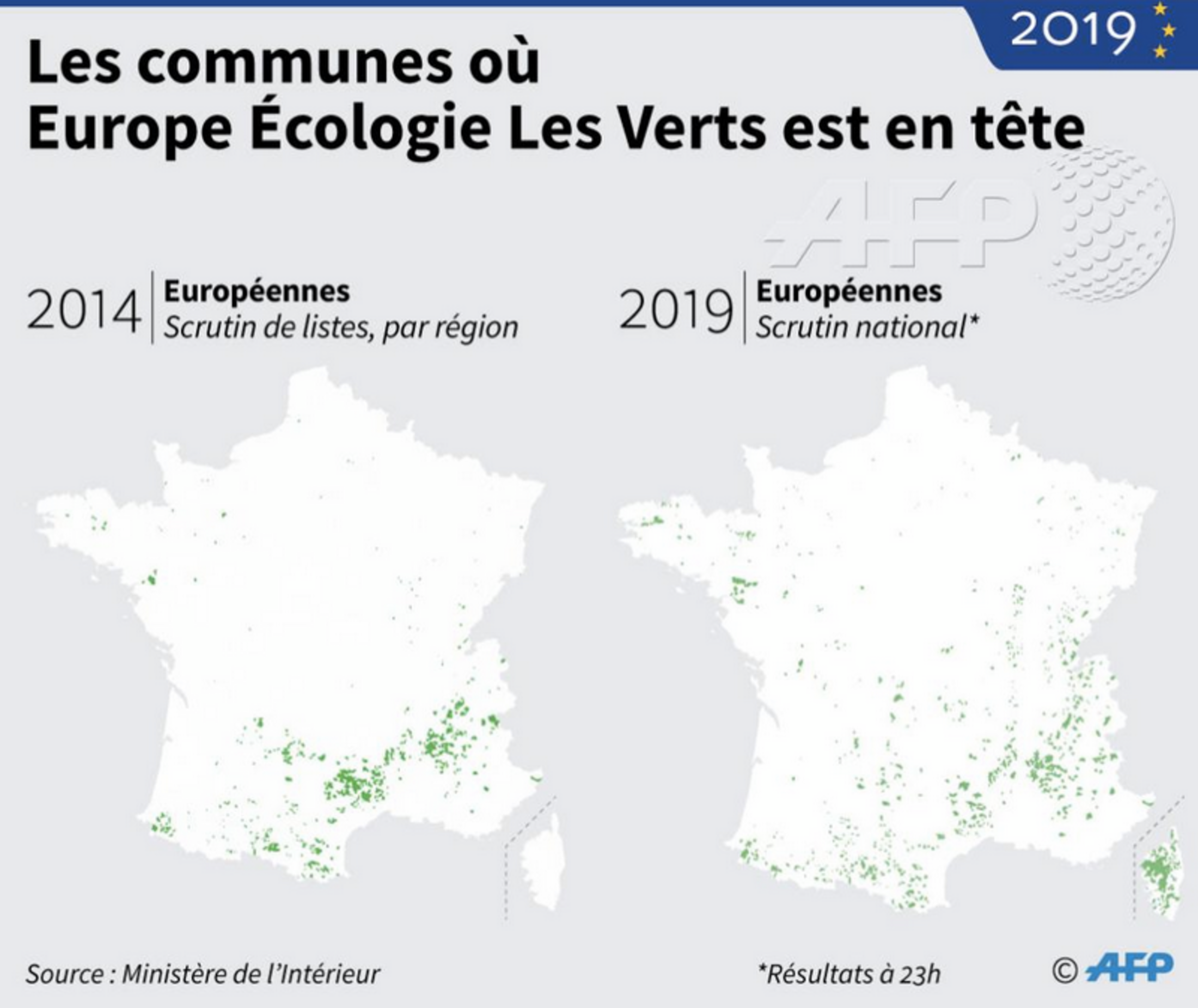

The EELV did particularly well in Corsica, where the nationalist Gilles Simeoni supported them. It also performed strongly in the so-called environmental 'Y' zone which, according to the LREM's Pascal Canfin, stretches from the Hautes-Alpes département or county in south-east France to French Basque country in the south-west on one side and the Périgord in south-west central France on the other, passing via the départements of the Isère, Drôme, Ardèche and the Gers in southern France. In a book he wrote in 2014 Canfin, now an LREM MEP but who served under President François Hollande as a minister, saw the emergence in this area of what he termed a new “environmental society”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The task facing the Left

Apart from the EELV, no other list on the Left got over the 10% threshold. The disaster had been predicted and it duly turned into reality. Indeed, only two left-leaning groups achieved more than 5%, with La France Soumise and the Socialist Party neck and neck on just over 6%. Despite media success in television debates and on social media, Ian Brossat's communist list attracted under 3% of the vote, as some activists on the ground had feared.

The former PS leader Benoît Hamon did slightly better, attracting just over 3% of the vote for his list, but he failed to win any MEPs in what was the first electoral test of his new movement Generation.s. The political future of both it and its founder now seems uncertain.

But it was La France Insoumise, the movement which up to now had been the torch bearer on the Left, which suffered the biggest disappointment among left-wing groups on Sunday. Its leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon had been fourth in the 2017 presidential campaign and he had been the dominant figure on the Left by some margin. But on Sunday the party's list, headed by Manon Aubry, came only just ahead of the PS list.

The fault for this poor performance lies, among other things, in a movement that has been increasingly criticised for a lack of democracy in its methods, a series of departures – including one candidate who left to join the far-right RN - and a campaign strategy that was not always coherent, veering between appeals to a radical left and green audience, in line with the head of the list Manon Aubry, and a more populist-style approach, sticking to the supposed agenda of the 'yellow vest' protest movement. The poor performance is also – and perhaps particularly – due to the personality of leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon himself, who has alienated a part of the electorate.

If one compares LFI's vote on Sunday with recent European elections there is a clear sense of the party going back to where it stared from. In 2014 the movement, then known as the Front de Gauche, polled 6%, more or less the same as it has just achieved. At the time the communists were on the same list. In the 2017 Parliamentary elections, where the turnout was similar to this poll, the LFI scored 11%. This was already far behind the 19% polled by Mélenchon in the first round of the presidential election.

It hasn't all disappeared

However, the shattering of the French Left does not mean that it is completely dead in electoral terms. The dissipation of the vote should not hide the fact that the total proportion of those who supported green or left-wing lists was over 30%. That is more than in both the first round of the 2017 Parliamentary elections and the first round of the presidential election earlier that same year.

As Anne Jadot, a lecturer in political science from the University of Lorraine in the north-east of the country, said on Mediapart's election night programme, the result in fact marked “the halt in relative terms” of the breakdown of the Left. But at the same time it gives few clues as to how the Left can be put back together again.

All that is clear is that, after two years of domination by La France Insoumise, the greens are now in pole position on the Left. To use the expression employed by Christophe Bouillaud, professor of political science at Sciences Po Grenoble university in south-east France, an opportunity for the Left to adopt an “ecological and socialist solution” could now open up.

The academic says that the French Left now needs to undergo a deep examination of its conscience. “Why in the last 30 to 40 years have so many people started on the Left and then finished up on the Right?” he asked on Mediapart's election programme. He pointed to the origins of Emmanuel Macron's policies or 'Macronism' as a form of “Thatcherism which incubated within a party of the Left”, referring to the current president's own past ties with the Socialist Party and his key role in President François Hollande's socialist presidency.

One unifying initiative that may bring the disparate parts of the Left together could be the referendum that is taking place against plans to privatise the organisation that operates the main airports in Paris, Aéroports de Paris (ADP). This will in theory be a chance to combine an environmental and socialist approach, and give the various factions a chance to reinvent themselves ahead of the local elections which take place in France in 2020.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter