Its challenge is how to move from being a movement of fans to a party of activists. As it held its second party conference on October 21st, the ruling La République en Marche (LREM) faced the question of how to progress - to survive even - outside election campaigns. Even though the next major elections, for the European Parliament, take place in May 2019, the party still has to mobilise its registered members – they do not have to pay to join – if it wants to implant itself locally.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“Basically we can now see that what happened in 2017, with the election of Macron, was that a narrative was constructed very quickly, one which rests a little bit on sand,” says political expert and academic Luc Rouban, author of Le Paradoxe du Macronisme, published by Les Presses de Sciences-Po. The party now needs to gather this sand together so that it does not all blow away.

Indeed, following its stunning successes in the presidential and Parliamentary elections in 2017 the LREM finds itself having to take action in order to avoid losing members and seeing its influence at grassroots level evaporate. But this is easier said than done when “three-quarters of 'marchers' (76%) had never been involved in a political organisation before joining LREM”. And when “almost as many (73%) had no experience of trade union involvement, which has sometimes served as an antechamber to political activism in the past,” as stated in a recent study by the think tank Terra Nova, entitled 'La République en marche : anatomie d’un mouvement'.

The LREM leadership is aware of the issue. One of the four priorities the party has established for the coming year is to “do politics differently”, which was the subject of a specific workshop at the recent party conference. Behind this expression is a desire to put in place and strengthen measures to encourage and help members on the ground who are inexperienced in political activism.

A member of LREM's executive bureau, Jean-Marc Borello, does not hide away from the urgent need to act in order to avoid the party's base crumbling away. At the party's conference Borello, the founder of Groupe SOS, which works in the social economy, recognised that training was a “real issue”. The objective given to party members is to “change the world around them” in particular through citizens projects. This requires a “serious diagnosis as to what works and what doesn't work” and to ask the question as to “how can you change things and make sure that things change?”

LREM's spokesperson Laetitia Avia told the conference that members needed to be “participants in public and political life”. To achieve this she asked them to “accentuate and discuss good practice” as well as working with “LREM's collaborative tools”. It is these “tools” that are at the heart of the party's attempts to incite its members to continue to go out and campaign, to relay the views of the ruling party and to try to implant itself locally.

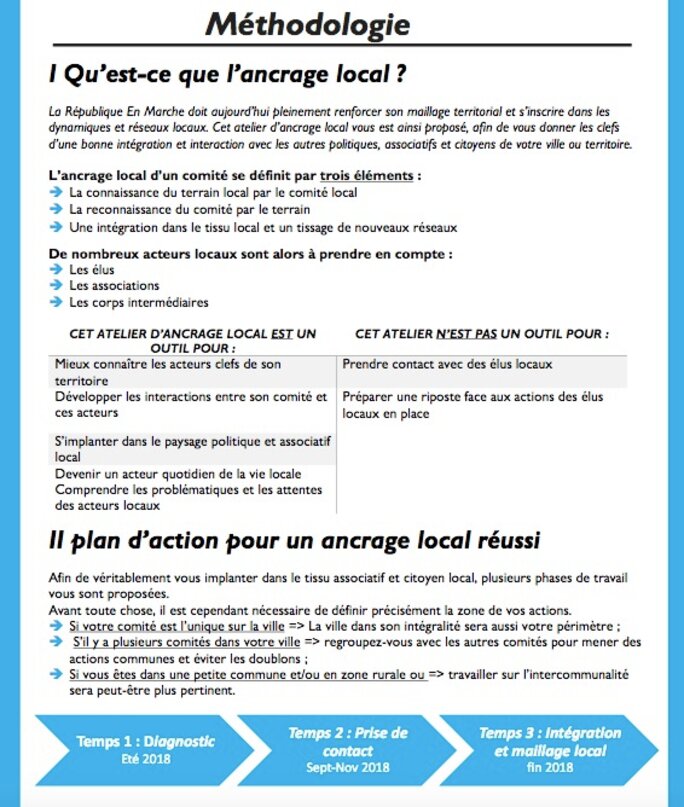

Enlargement : Illustration 2

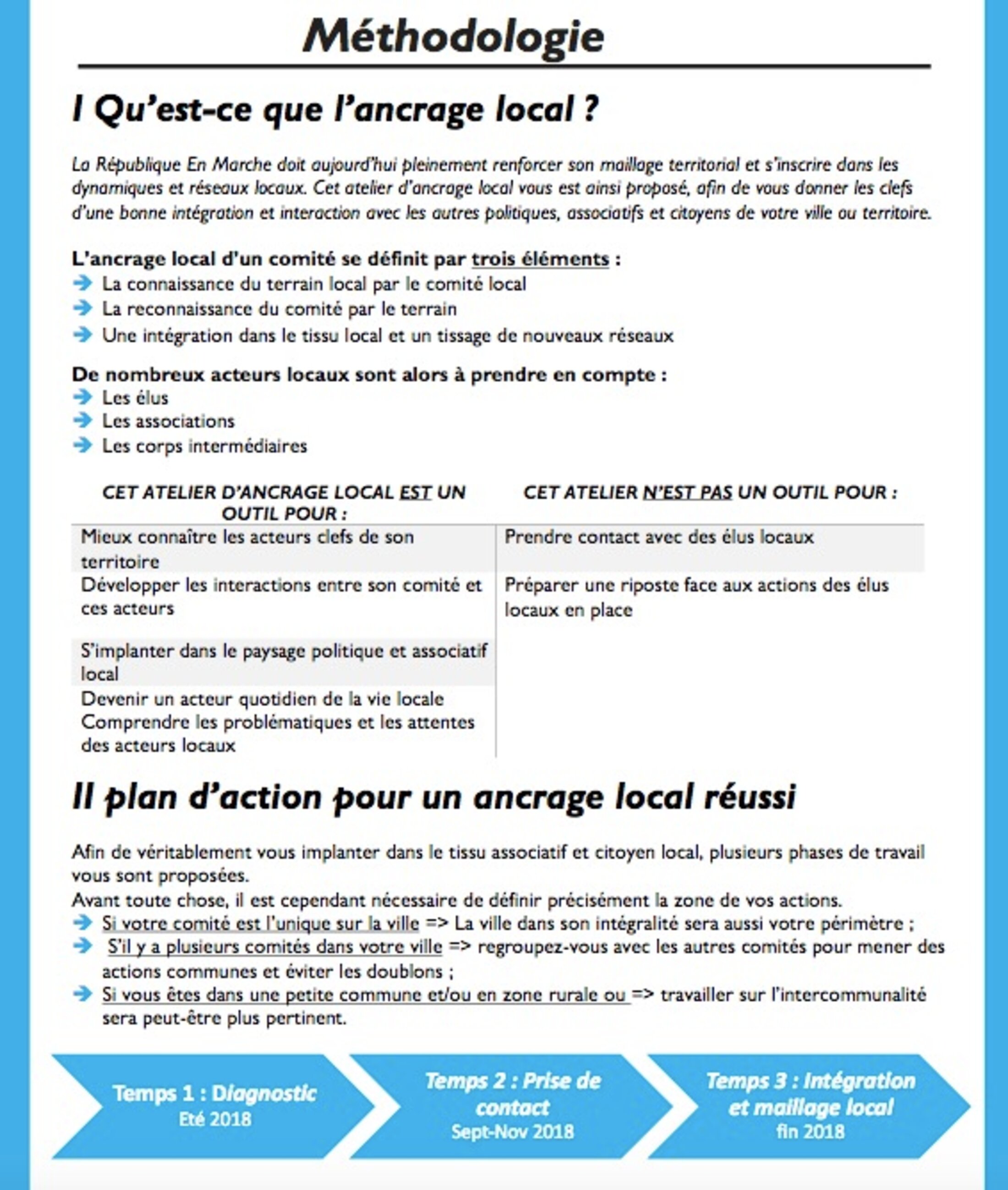

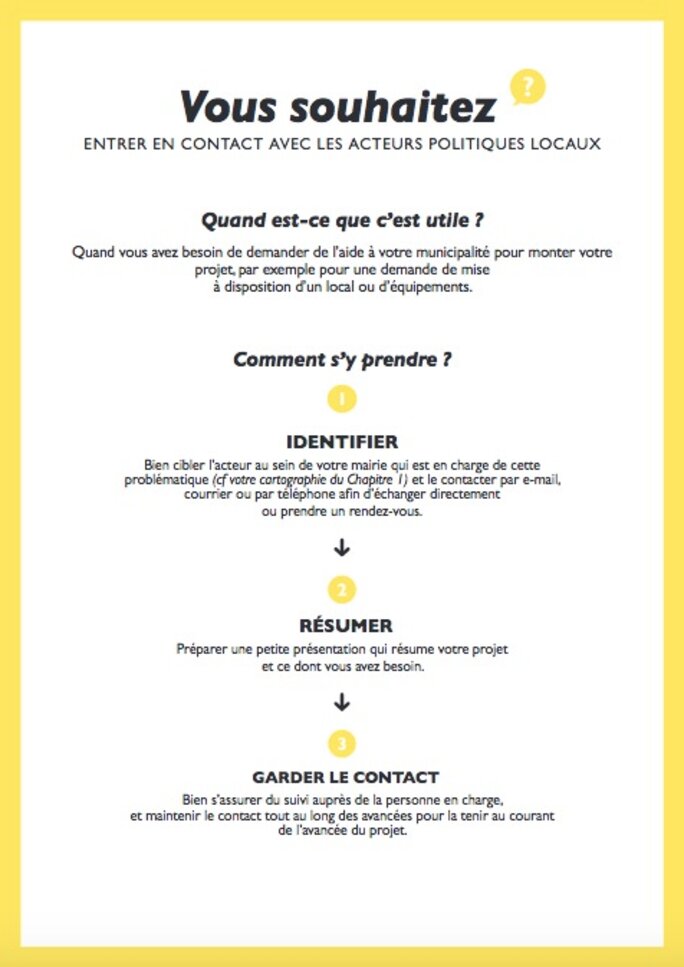

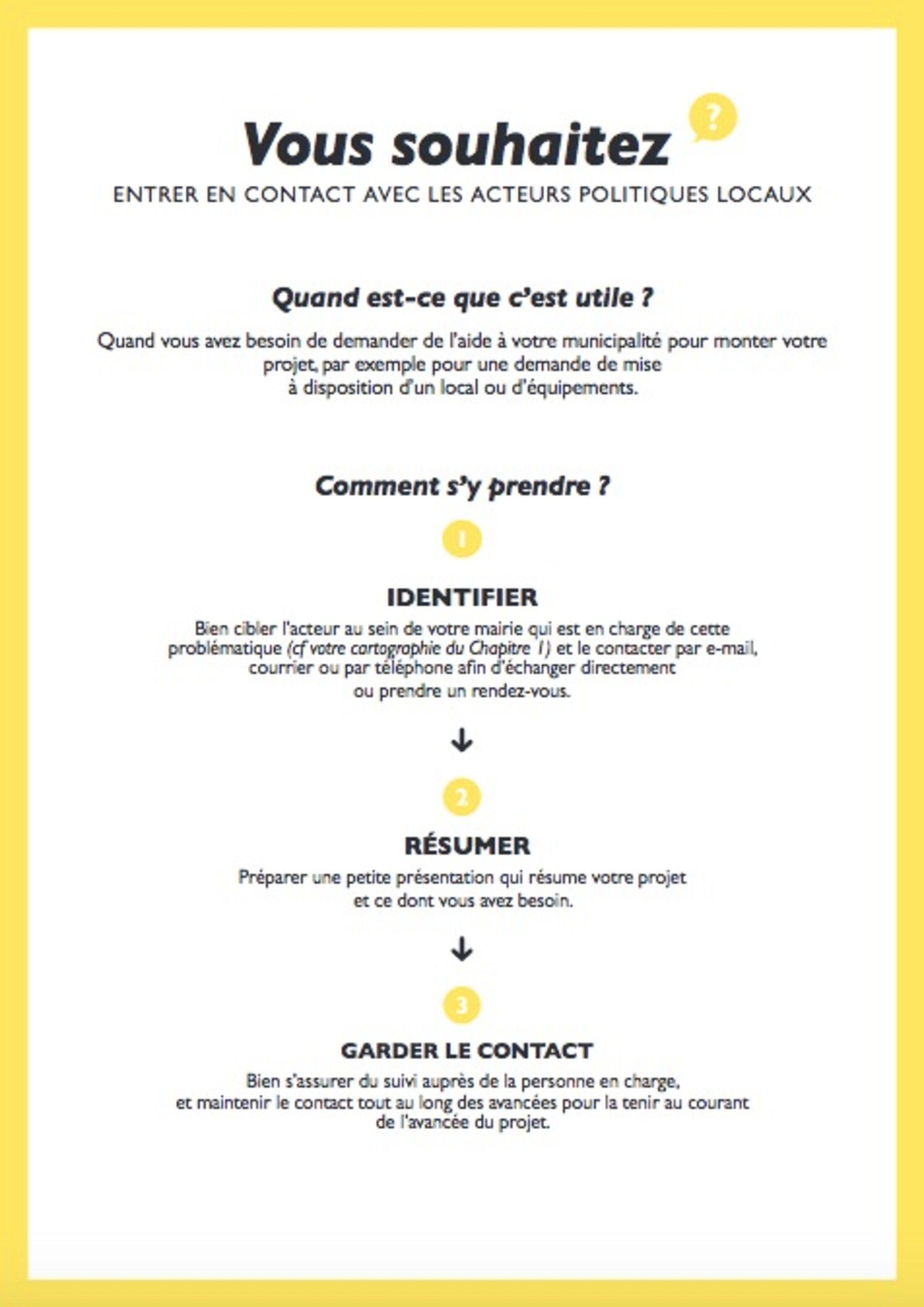

Emmanuel Macron came up with the idea of France becoming a “start-up nation”; now his movement is seeking to act like a “start-up party” to resolve its issues on the ground. Online learning via MOOC, microlearning, turnkey methods to run workshops, the mapping of local areas to help implant themselves; all these trappings of kit-form politics have been put in place and pushed to their limits to keep the activists busy and also to train them.

Mediapart has seen numerous internal LREM documents which show the scale of the strategy with its emphasis on management tools strongly inspired by the world of business. The strategy is laid out, step by step, to guide the activists and lead them towards their goal.

That is the case, for example, with the issue of “local integration”, the term used within the party to describe activists developing political roots on the ground ahead of local and regional elections.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

As is shown in this document above, which explains the organisation of a workshop on the theme of local integration, everything is planned and placed in order, using terms such as “action plans” and “progress points”. It is all very similar to the rolling out of a business or professional programme.

So, for example, the staging of a workshop is minutely laid out: ten minutes for an introduction, 20 minutes for mapping an area, one hour 20 minutes on identifying and prioritising the actions to be carried out, and ten minutes for the summing up. The result is a two-hour meeting which is completely standardised and laid out.

'A rationalisation of activism pushed to the extreme'

The example of citizens projects, a flagship measure of LREM-style activism, is even more telling. Since the spring of 2018 LREM has been urging its members to get as close to the grassroots as possible by launching social, employment, educational or digital access projects, or projects to do with the energy transition to non-fossil fuels. A charter was drawn up to inform interested members. Officially around 500 citizens projects have been launched, though this figure is impossible to check.

However, starting a citizens project is no easy matter, especially when there is no local base or experience of activism. So LREM has set out in simple terms how to carry one out, so that members can indeed “do politics differently” on the ground. In September Christophe Castaner – now interior minister but then director of LREM – announced the launch of “turnkey projects”. These are in effect political kits that are ready to use to make activist life easier. There are videos about them designed to encourage members to get involved.

Just as with the sale of any product, terms and conditions have been written for these activist tools. So members who are interested can find out what a 'Person in charge of Citizen Engagement' ('REC' in French) is through eighteen precise definitions. The party describes the “person carrying out the project” as the “member who presents a citizens project to [LREM]” with a view to it being accepted and put on the party's website of approved projects.

All actions are then channelled, supervised and subject to the rules already set out by headquarters. Should a citizens project fail, then the party has planned for that too. In the terms and conditions it states that anyone running a project can appeal for personalised help but that “in no case does this place an obligation in terms of results” on LREM or the 'Person in charge of Citizen Engagement'.

“Above all, these documents confirm the idea of a desire to reinvigorate activism outside of an electoral campaign. In a young party there's a fear of losing momentum,” says Anaïs Theviot, a lecturer at Angers University in western central France and a specialist in political activism.

The academic says that some of the LREM documents remind her of those the Socialist Party sent to members to train them in door-to-door campaigning during François Hollande's 2012 presidential campaign. But Anaïs Theviot sees LREM's way of going about things as a “a rationalisation of activism pushed to the extreme” with a “start-up mindset” using “management speak”.

Jonathan Bocquet, who has a doctorate in political sciences at Lyon 2 University, highlights the “management aspect of the project” shown in the strategy of developing a grassroots presence. But beyond that, he says the documents indicate “the idea of a brand to be built. To come together around a project which is not fundamentally or not exclusively political. Here again, this is not specific just to LREM but it is without doubt more marked. This is even more the case given that the party has no past and so the links between members have to be built on something other than a mythology or hall of fame [editor's note, of past political figures],” he says.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

But does the party really need to implement this 'kit-form politics'? The content of the Terra Nova report on LREM suggests it does, given that the movement is struggling to train its members. “Two activities, however, seem to have greater success among its members: these are, on the one hand, the passing on to other people of information, files or useful links, and on the other the contribution to LREM's ideas (via Telegram or online consultation),” write the report's authors. The discussion and debate of ideas thus remain the most popular activities for the most active members, who seem to lose interest in the citizens projects or actions to implant the party locally, the issues which are the subject of the tutorials and other 'tools' developed by the party.

“LREM is a UFO, it has to find its place,” says Pénélope, who was involved in the 'projects' unit at the party's headquarters for a year before her short-term contract came to an end. “Everyone can make themselves useful according to what they want to do,” she says, referring to the wide range of options that LREM now offers its members. “For example, we offer a kit method for cleaning the streets,” she says. “Not everyone is the head of a project!”

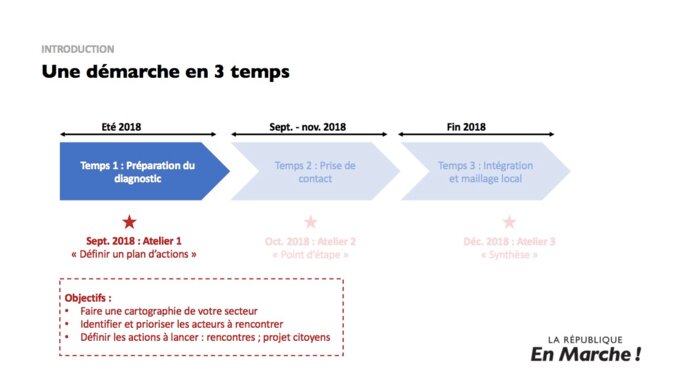

However, in common with some party activists who have spoken to Mediapart about their dismay, Anaïs Theviot points to a “certain infantalisation” in the party's approach. “It is all very supervised, with some rather simplistic fun quizzes as a bonus,” says the academic. She refers to an internal document on the online learning courses MOOC which the party makes available to the public. In a document entitled “MOOC meeting, chapter one, Methodology” one idea is to create a quiz. The proposed examples, on the issue of getting involved in the local area, are rather basic in nature. One asks: “How many regions are there in France?”. Another asks: “Who is in charge of middle schools?”. They highlight how far some activists still have to go in order to know their political surroundings.

One female activist from Paris who left the movement in June 2018 told Mediapart in September: “They treat people like children; anyway, the little Macron supporters have no political culture.” She added ironically: “I learnt managerial newspeak, I learnt to use the tools. But none of that adds up to politics.”

In a confidential document entitled “How to reinvigorate local committees”, written in an independent manner by one of the 'marchers' and based on 3,000 messages from 389 contributors, the authors proposed going further than the “workshops spoon-fed by HQ” which irritate the more active members. The party cannot remain deaf for much longer to the criticisms of its start-up strategy.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter