A huge leak of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, was discovered earlier this month by French utilities giant EDF at its nuclear power plant at Tricastin in south-east France, in the latest of a series of accidents at the site, one of the oldest in the country, over recent years.

The vast spill of tritium, which sank into groundwater below the plant, was discovered on December 11th, when a piezometer recorded tritium activity in the water with radioactivity measured at around 8,000 becquerels per litre (Bq/l). The following day, further tests found the radioactivity had soared to 28,900 Bq/l.

By comparison, the normal background levels of tritium radioactivity in non-polluted ground water are between 1 Bq/l and 2 Bq/l, according to a 2020 report commissioned by Greenpeace from the Commission for Independent Research and Information about Radiation, the CRIIRAD, an independent French NGO.

Tricastin, which lies in the valley of the River Rhône close to the town of Bollène, operates four pressurised water reactors (PWRs) which progressively entered service between 1980 and 1981. It has been plagued by several recorded incidents of lesser tritium leaks over the past four years, and a serious uranium spill in 2008 (one side-effect of that was a fall in sales for vineyards in the region, whose wines were sold under the appellation of Coteaux du Tricastin, and in 2010 they gained authorisation to change the AOC to Grignan-Les Adhemar).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

On December 15th, EDF informed France’s nuclear safety watchdog, the ASN, that a “significant event for the environment” – the official terminology of "significant event" is used by the ASN to describe accidents of “particular importance” – had occurred at the plant. The accident was rendered public by EDF in a statement released on December 20th.

In that statement, EDF detailed that the spill had occurred after the overfilling, on November 25th, of a tank that sends radioactive effluent from the plant for storage in reservoirs which are emptied after measurement of pollutants. It said the overfilling of the tank led to 900 litres of the effluent spilling into an area for collecting rainwater and subsequently, after several days, infiltrated the groundwater.

In the statement, EDF said that “this event has no consequences for health” because the groundwater in question is contained within a geotechnically engineered and confined substructure underneath the plant, and which is entirely separated from the wider underground water table, a claim disputed by the CRIIRAD.

The substructure, which lies directly below the surface area of the plant, is lined with 60-centimetre-thick concrete walls which descend 12 metres underneath. At its bottom, it is lined by marl, a sedimentary rock of clay and lime, supposedly impermeable. The groundwater inside it lies lower in the ground than that found elsewhere around the site in order to isolate it.

In its statement published on December 20th, EDF said that the radioactive measurement of the groundwater had “today” fallen to “around 11,000 Bq/l”.

In a statement published on December 23rd, the ASN nuclear safety agency, which sent inspectors to Tricastin on December 21st, said that it was satisfied that the tritium spill was “confined” within the site’s geotechnical substructure, and had therefore recorded the incident as being at “level zero” according to the International Atomic Energy Agency’s criteria as defined in its International Nuclear and Radiologic Event Scale (INES).

The ASN said that its inspection at the plant confirmed that the overspill was caused by “failings in the alarm sensors” that monitor the levels of the effluent tanks, adding that it had asked the EDF to provide it with the results of the daily radioactivity measurements taken from the “internal” groundwater within the substructure. “No contamination of the water table outside the site has been revealed”, it insisted.

But Bruno Chareyron, a nuclear physics engineer who is director of the CRIIRAD’s research laboratory, rejects the notion that the tritium is safely contained in the substructure. Questioned by Mediapart, he said tritium is “particularly mobile”, and “susceptible to seep through 60-centimetre concrete walls”, and that the casing of the geotechnical substructure “therefore cannot be considered impermeable to tritium”.

In a 2018 report, ASN inspectors who had visited the Tricastin plant following a previous leak of tritium noted that EDF “representatives” had indicated to them then that it could not be “totally excluded, given the state of the joints between buildings” that the radioactive discharge had seeped into the ground or the groundwater”. In an emailed reply to questions submitted to it by Mediapart, the ASN insisted that “the joints placed in question in 2017 and 2018 have been repaired”, adding that “a new maintenance procedure was put in place in 2019” to reinforce “control measures”, and that “these joints are not implicated in the event of 25/11/2021”.

Also questioned by Mediapart, EDF said that “the strengthened surveillance put in place allows for the confirmation that the samples taken from the water table by the control wells situated on the outside boundaries of the plant are in accordance with the levels habitually observed, to the order of between 10 and 25 Bq/l”. But that remains very high when compared to the CRIIRAD’s estimation that non-polluted water should contain no more than 2 Bq/l.

Between November and December 2019, during another leak of tritium at the Tricastin plant, the radiation levels in the groundwater within the substructure of the plant reached 5,300 Bq/l , well above the 1,000 Bq/l ceiling above which an incident must be declared, when the ASN was again alerted.

Beyond these recorded incidents within the plant, it regularly tips effluent contaminated with tritium, after it has been mixed with non-polluted water, into the Donzère-Mondragon canal that runs alongside the site, and which ultimately reaches the River Rhône. The river, which runs from the Swiss Alps west into France and then south all the way to the Mediterranean Sea, is systematically contaminated with tritium not only from the Tricastin nuclear power station but also from others; that of Bugey, near the city of Lyon, Saint-Alban and Cruas, all to the north of Tricastin, and also the Orano nuclear retreatment plant close to Tricastin at Pierrelatte.

The contaminated matter is of course diluted by the rate of flow of the Donzère-Mondragon canal and that of the River Rhône, but radioactivity inevitably remains in the alluvial channels, from which nearby villages and towns draw drinking water. The CRIIRAD has warned that because the pollution monitoring of the water is “most often” carried out every three months, “They are therefore susceptible to very strongly under-estimate the effective contamination of the water” ingested by the local communities. That is notably so if the tests are carried out at a moment when the rejected effluent was low in pollutants.

Tritium ingested in the human body through water is usually rapidly eliminated, but if absorbed in food its radiation activity is stronger and longer-lasting. If it binds with a person’s DNA it can lead to mutations of chromosomes and cause cancers. “Tritium radiotoxicity appears to have been largely underestimated and little work exists on the long-term effects, notably genetic, of contamination by this radioelement,” said CRIIRAD laboratory director Bruno Chareyron.

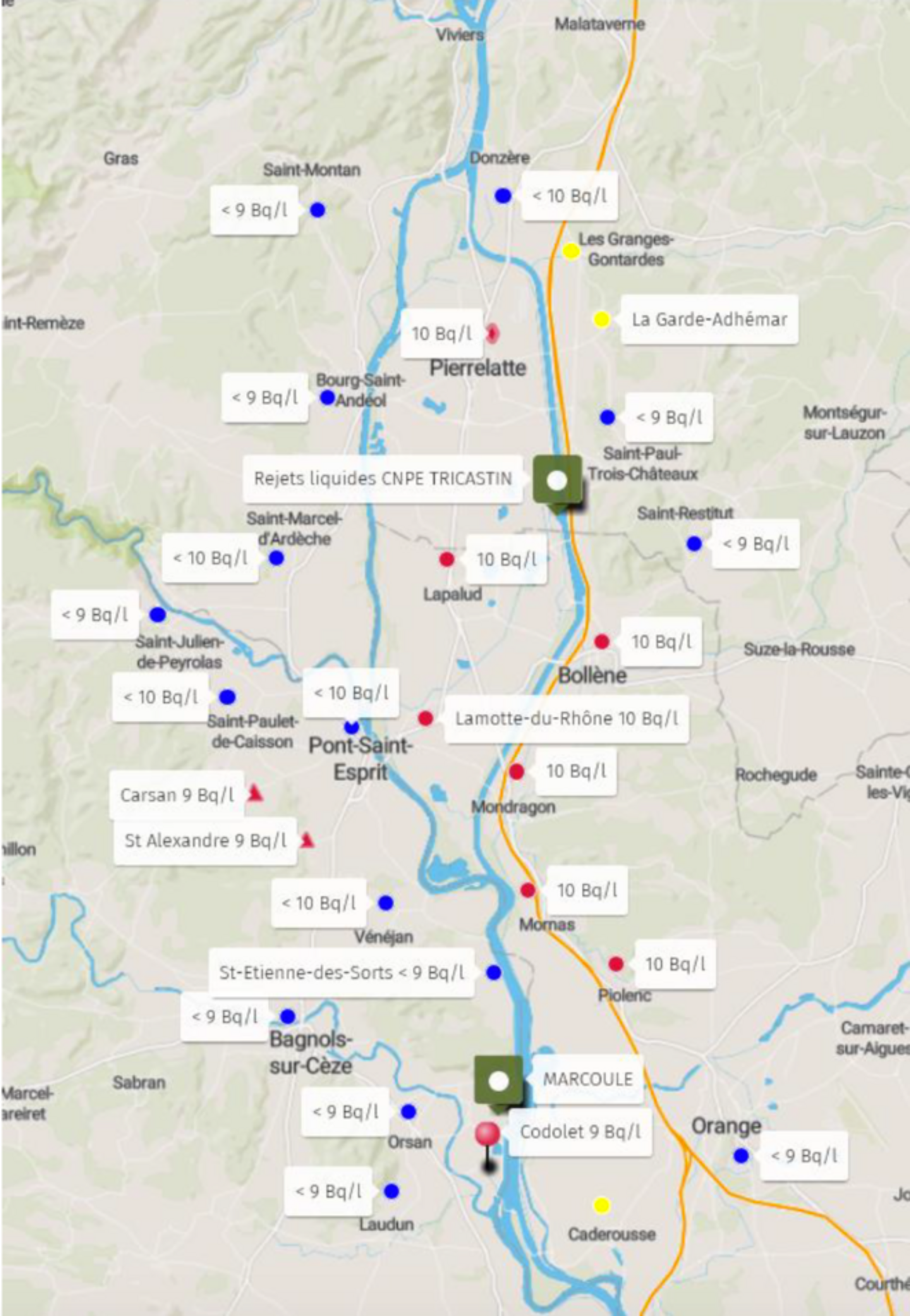

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The presence of tritium in drinking water used by the population close to the Tricastin plant is regularly monitored, usually at three-monthly intervals. Using data from the monitoring tests carried out between 2016 and 2019, sourced from the French heath ministry, the CRIIRAD created a map (see above) indicating the average tritium activity found in the drinking water of towns and villages along a roughly 40-kilometre stretch of the Rhône Valley running downriver from Donzère, about seven kilometres north of Tricastin.

The CRIIRAD observed that “the inhabitants of numerous municipalities situated south of Tricastin regularly drink water contaminated with tritium”. While the contamination of the tap water was well below the safety limit applicable in France, for Chareyron it remains unacceptable. “Is it normal to provide several tens of thousands of people, including young children and pregnant women, drinking water that is contaminated by a radioactive element discharged by a nearby nuclear power station?” he asked.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report is available here.

English version by Graham Tearse