In June 2012 Valérie Trierweiler became embroiled in a damaging public row over a Tweet she sent in the lead up to that month's parliamentary elections. Trierweiler publicly backed dissident socialist candidate Olivier Falorni against the official Socialist Party candidate Ségolène Royal in the La Rochelle constituency in south-west France. Royal is the mother of François Hollande's four children and the women whom he left for Valérie Trierweiler. Falorni later went on to win the seat. In October 2012 Trierweiler publicly admitted the Tweet had been a “mistake”. Below is Edwy Plenel's original article on the issue, first published on June 12th, 2012.

-------------------------------------------

The Twitter affair involving Valérie Trierweiler is not just another news story, it has political importance: it shows how the public domain gets privatised when private matters get publicised. The journalist is seeking to intervene in socialist squabbles, by asserting her preferences and dislikes. But being neither an activist nor an elected representative, nor having any known political involvement, she is in absolutely no position to do so, other than through being François Hollande's partner. We did not elect a couple, but a president - and one only - who must re-establish the line between political functions and private lives. Unless, that is, he wants to continue the path followed by the previous president Nicolas Sarkozy, with its conflicts of interest and blurring of functions. And wants to face the same rejection.

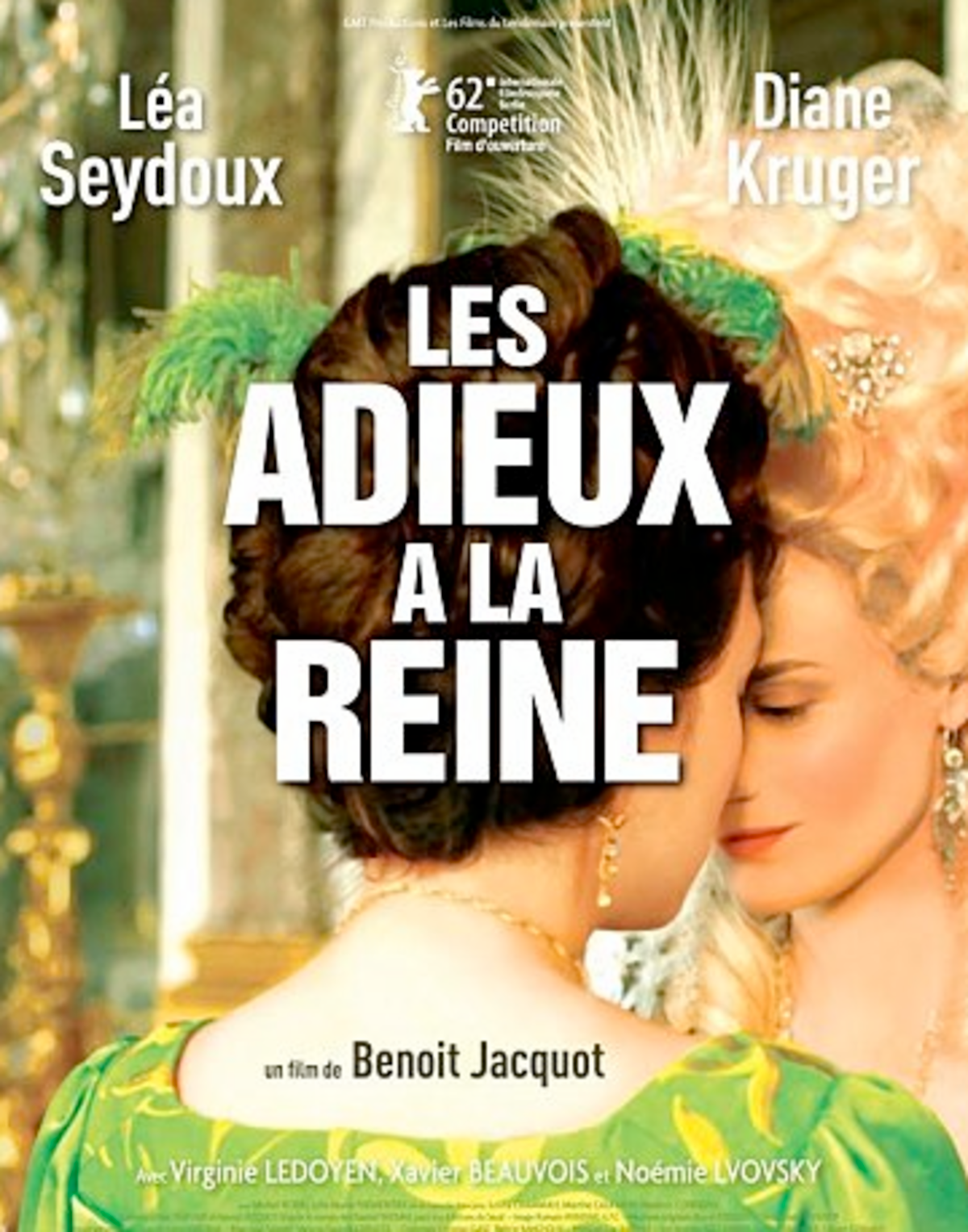

It is time to say our goodbyes to the First Lady, just as the first republicans bade farewell to the queen during the French Revolution. Les Adieux à la reine (' Farewell My Queen' in the English version), the latest film by director Benoît Jacquot, came out in March 2012 just two months before the presidential election. Adapted from the 2002 novel of the same name by academic Chantal Thomas, it portrays the torment of Marie-Antoinette at the dawn of the French Revolution, enclosed as she was in an artificial bubble created by the mingling of power and seduction, with their various duties and desires becoming intertwined. Set in the summer of 1789, at the time when the Bastille was stormed, the novel itself is based on a fine essay written by Chantal Thomas that was published for the bicentenary of the revolution in 1989, La Reine scélérate ('The Wicked Queen' in the English version).

Subtitled Marie-Antoinette dans les pamphlets ('The Origins of the Myth of Marie-Antoinette' in the English version) the essay shows how the fall of the monarchy was accompanied by a wave of popular rejection of a queen who had previously captivated the people with her charm. A foreigner and a woman, Austrian, thus seen as an enemy of France, and beautiful - therefore seen as wicked – she was the target of misogynist and xenophobic cabals that formed during the dynamic process that swept away the Ancien Regime. The essay reveals a lucidity at that time which republicans of today would be well advised to use as inspiration. From as early as 1789 a revolutionary journalist, Camille Desmoulins (1760 – 1794), wanted to stop this profane anger by saving Marie-Antoinette from the status that would, inevitably, lead her to the scaffold.

Desmoulins proposed that the word that caused this terrible outrage - “queen” - should simply be banned. He wrote: “If ever two words should have been astonished to find themselves together it would have been these: 'Queen of the French'.” He then added: “Marie-Antoinette is the king's wife, and nothing more.” This gave rise to his “motion”, which was never taken up, in which it would have been “forbidden in public life to use this word 'queen' of the French” because it “reeks of servitude”. Two years later, in 1791, Olympe de Gouges (1748 to 1793), a forebear of modern feminists, dedicated her famous 'Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen' to Marie-Antoinette, urging her to wed herself to freedom rather than tyranny.

More than two centuries ago these pioneers of republican hope had started to see what our persistent Bonapartism still wants to conceal from us: that unshackled personal power concentrated in a single figure will inevitably lead to the abuse of power, unfettered egoism and irresponsible individualism. They saw, too, how the conferring of a supreme position on just one person ends up extending its corruption of the public individual to those closest to them, making them lose sense of their responsibilities and duties. So there should be no queen of the French people, they warned, before resolving to get rid of the king himself, having been unable to make their demands understood.

To which we can now add that there should no First Lady in the French Republic either, in the certain knowledge that if this warning is not heeded, François Hollande can already say goodbye to the success of the “exemplary presidency” that he promised. For the Twitter affair, in which Valérie Trierweiler admits calling on people to support a dissident socialist against the official Socialist Party candidate who has nothing to do with her - other than the fact that that party candidate happens to be the ex-partner of her partner who has now become the head of state - raises all the old concerns that were present under the monarchy, about arbitrary acts by the king (or the queen), royal whims and the mood of the court.

The privatisation of presidential power

Throughout the presidential campaign in 2012, and with the willing complicity of a press debased by gossip and tales of romance, Valérie Trierweiler endlessly toyed with these two words: First Lady. She used them, repeated them, commented on them and then, at the last minute, on the day her partner was sworn in as president at the Elysée, she judged the title inappropriate (see video here). Yet from an institutional point of view, there is not even a debate to be had: there has never been a 'First lady' in the French Republic. It is neither a status nor a function. In truth it is simply a turn of phrase that the Nicolas Sarkozy presidency, and it alone, tried to make official.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It was after Sarkozy's divorce from his second wife Cécilia and his prompt remarriage to Carla Bruni – a love story that brought vaudeville to the Elysée at the same time as bling-bling arrived there – that this expression (the French words 'Première Dame' are a direct translation of the American term 'First Lady') made an appearance on the official site of the Republic's presidency (see left). At the time we at Mediapart highlighted the extent to which, under the guise of celebrity, this operation concealed the privatisation of the highest public office, for which the model and singer Carla Bruni became the symbol, to the point that she posed on the roof of the Elysée Palace itself for a magazine shoot.

On the evening of May 6th 2012, when François Hollande was elected, we thought we had seen an end to these harmful liberties which damage the common good, pay no heed to the notion of republican equality and dishonour public dignity. Yet, after a promising start that combined a soothing sense of reserve with rigorous uprightness, here we are with the new president stumbling over an obstacle of a similar kind. In fact, the public invitation by Valérie Trierweiler for voters not to elect Ségolène Royal to the National Assembly – an action she has openly admitted – involves the very same transgressions. The president’s partner assumes the right to prerogatives she does not have, other than by claiming that her private link gives her a public privilege.

Trierweiler herself will object that she is a journalist who has been in the political arena for a long time, and that she intends to continue to be so in the editorial team at Paris-Match. But we have no memory of any journalist from this weekly publication – or any other group or press title – ever having taken a position on the internal divisions of any political party. It's the business of the party's activists and its leaders, which one can certainly comment on, but which one should not try to arbitrate on in their place, to the point of telling people which way to vote.

This point is reinforced by the fact that before her relationship with François Hollande, Valérie Trierweiler, an employee of the Lagardère group and, at one time, a television channel owned by the Bolloré group, had never been known for her political commitment, whether in her professional life or as a citizen. No self-proclaimed political activism, party membership or involvement in electoral campaigns. That is her right and perfectly respectable. But if we mention this it is to underline that the equal media coverage afforded to her compared with Ségolène Royal has nothing at all to do with what really matters to us; which is public life and political leaders.

Whatever one thinks of her, her personality or her political career, Ségolène Royal did not get into politics by the back door. She has devoted her life to it for thirty years, received and dished out some blows, accepted her victories and her defeats at the ballot box, defended her positions and fought her battles. Independent of her personal relationships, her political life is her raison d'etre, and it has been an unrelenting assault on what was until recently, throughout history and in all corners of the globe, the place that the historian Michelle Perrot called “the Forbidden City” for women. Namely politics. To claim that what we have here is a duel between women (see for example this example, in French, in Elle magazine ) is to accept the diminishment of our public life through its privatisation.

For it would be hard to say just what the political stakes are for Valérie Trierweiler in this affair, whereas on the contrary what's at stake for Ségolène Royal's campaign is quite explicit – the chance to become an MP and the first female president of France’s National Assembly. If, like all of us, Valérie Trierweiler occasionally has unkind thoughts about people she doesn't like, than that's simply a normal human trait. But for her to act publicly on those thoughts is an error, a lack of common decency and civility, aggravated by the fact she believed she was protected by the authority that had conferred on her the imaginary position of 'First Lady'.

A setback for the women's cause

One can easily imagine the confusion of people on the Left, indeed of anyone, faced with this indecent display with its virulence and ridicule. Establishing the boundary between private and public is at the core of any attempt to build a democratic space that is pluralist, calm and properly regulated, as part of a rational attempt to keep personal passions at bay. We had already learnt, and not without some surprise, that the evident tension that affected the Socialist Party in 2007 - its first secretary and natural candidate for the position, François Hollande, was not standing in the presidential election, while his partner, Ségolène Royal, was – was also concealing a couple's secret rift (1). But this Twitter episode sheds light on a recent comment by Valérie Trierweiler about her attitude to voting in the 2007 presidential election. While describing herself as of the Left, she was unable to bring herself to vote for the socialist candidate Ségolène Royal and preferred to abstain. “As if I felt uninvolved. Or, more precisely, too involved. It was painful,” she said.

In 2012 as in 2007 the ethics of political conviction, every bit as much as the ethics of responsibility, were undermined by emotional reasons that political reason should ignore. But in the meantime François Hollande has become president of the Republic and faces the risk that this office, which in theory belongs not to him but to the nation, might once again be appropriated by 'presidentialism', its court, courtiers, favourites, privileges, its ability to confer favours, its impunity. Yet the “exemplary” presidency proclaimed by the new president, following the disaster of the “irreproachable” presidency promised in 2007 by Nicolas Sarkozy, was supposed to put an immediate stop to all temptations, excesses or losses of control that could lead to such failings.

We therefore have to end this illusion of a First Lady and, as prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault advises, invite the president of the Republic's partner to be discreet from now on and not attempt to play a political role which she has not worked for, campaigned for or been elected to. This is also the best way of providing her with what is clearly so important to her, namely her professional freedom and her economic independence. For in this story the biggest setback has been suffered by the feminist cause, with the journalist herself reduced to helping out in what is seemingly still a man's profession. It is a position whose constraints have been described by Valérie Trierweiler herself during one of the many interviews given by the future 'First Lady'.

“I report to him what I hear and see,” she explained to Libération on April 7th 2012, during the election campaign. “Otherwise I make sure that his coat or scarf are close at hand. I also look after the tea and honey pastels for his throat: little things to bring a little relief in this hard campaign.” One can think of a more attractive portrait for a committed feminist...Reading these various comments one gets the idea that François Hollande's partner was wrestling with conflicting temptations, whether to play a role in power or to remain a professional journalist. Whether to think of herself as 'First Lady' or as a free woman.

Therefore one asked questions about the fact that she was given her own office at the socialist campaign headquarters, about her insistence at indulging in public displays of her affection for the candidate or, during the new president's investiture ceremony, about the way she greeted people after the president, something never seen before in Elysée Palace protocol. Which way was the balance going to tip? The removal of the “First Lady” entry on the presidential site was a promising sign (see the old link to it here), the sign of a sensible step back. Then came this Tweet whose devastating effect shows how much presidentialism, and its apparent power, is always at the mercy of its own excesses. A few days before, in the first article in her new role as an arts and culture journalist at Paris-Match, Valérie Trierweiler had identified herself with Eleanor Roosevelt (1884 – 1962) the “First Lady journalist” who, Trierweiler noted in an apparent hint at what she might herself want, had the privilege of recounting each day in a women's magazine the story of her life at the White House.

Unbalanced and with excessive powers, the French presidency is not like the American example, which is checked by strong counterbalances and by a lasting constitutional stability. And Valérie Trierweiler cannot cite the precedent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's wife, whose commitments long pre-dated his election as president of the United States. As our fellow journalist herself noted in her article, Eleanor Roosevelt supported the International Congress of Working Women, was an activist for the League of Women Voters and was active in women's groups in the Democratic Party. Indeed, no less an achievement than helping to draw up the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 was the crowning glory of a lifetime of commitment and activism.

If François Hollande's partner today wants to fight similar causes, and particularly the cause of women, then we can but encourage her. But it must be pointed out that when it comes to the feminist cause, she has just done it a disservice. Just as she has done the Left a disservice by becoming the symbol of the privatisation of presidential power. In the interests of both causes she must, as a matter of urgency, put an end to her dreams of being a 'First Lady' and become simply a journalist once more, by explicitly making it clear she will not exceed the limits of a role that the Republic never conferred on her.

The wife of President François Mitterrand, Danielle Mitterrand (1924 to 2011), had, with determination and discretion in equal measure, shown how to have untrammelled commitment to causes without ever seeming to abuse power. From this point of view the journalism that Valérie Trierweiler wants to pursue offers a thousand-and-one opportunities, whether it involves reporting on economic realities, social injustices, global imbalances, the financial crisis or unemployment and so on. And these areas are much more interesting than the contest the socialists are engaged in at La Rochelle in the Charente-Maritime, a contest that is as disastrous for the candidates concerned as it is devastating for their collective image.

--------------------------------------------------

1. François Hollande and Ségolène Royal, who have four children together, only announced their split after Royal lost the 2007 presidential election to Nicolas Sarkozy, even though the couple had been leading separate lives for some time, with Hollande having already started his relationship with Valérie Trierweiler.

--------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter