The Bettencourt affair, one of the greatest political-financial scandals of France’s Fifth Republic, is thus reduced to nothing more than just another human interest story: the tale of an old lady fleeced by several smart conmen. Illegal financing of politics; the handing out of sinecures and honours; pressure on the justice system; political scandal: the judges have come along with their red pens and none of that now remains. The double acquittal of Éric Woerth on Thursday May 28th – despite some harsh judicial comments in the judgement – just like the case being dropped against Nicolas Sarkozy in the same affair in 2013 – once again amid some tough judicial language - shows us once again that the justice system in France is in the same state as our democracy. In other words, it is suffering from a deep malaise.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Some legal experts will splutter at this claim and find a mass of procedural arguments and judicial quibbles to explain to us the lofty impartiality of a great justice system whose main concern is for individuals' rights and freedoms. Other legal experts could argue the opposite with the same aptitude. Let us steer clear of this debate among “indisputable” experts, one which is incomprehensible to citizens. The essential point remains. Having been profoundly reshaped over the last 20 years, from the code on criminal procedure to the renewed influence of politicians, from the supervision of careers to the submission of the prosecution to the executive, what should be our system of justice instead works like a machine designed to acquit the powerful.

It's not a question here of dusting down the old slogans from demonstrations of the past – 'Justice nowhere, police everywhere' – or to start a crusade against 'class justice' as was done, and with good cause, in years gone by. It is simply a question of acknowledging that in a democracy that is ailing, hesitant and monopolised by an oligarchy, and in a country where inequalities of all kinds are deepening amid general indifference, the justice system also forms part of this decline in values, ethics and public virtue.

Let's judge the truth of this, if one can say that in the circumstances. In the space of two weeks, several judicial decisions have increased the mistrust and anger felt towards the justice system. On May 18th, the criminal court of Paris decided to abandon all proceedings in the EADS affair in which, since 2006, executives at this aeronautical group, at French media firm Lagardère and car-makers Daimler, have been suspected of insider trading on a large scale. Now that the justice system has stopped the proceedings there will be no trial. On the same day revelations by Mediapart showed how the French bank Société Générale had managed to manipulate the investigation process, with the active support of the prosecution authorities, in the Kerviel affair. Now Parliamentarians are demanding that they should themselves look into this malfunctioning of the system and want a new trial as well as a commission of inquiry.

On the same day, too, the justice system acquitted two police officers implicated in the deaths of two teenagers at Clichy-sous-Bois on the outskirts of Paris in 2005, and who had faced charges of failing to help persons in danger. The system also removed from the victims' families any possibility of compensation, denying them the status of civil parties; under French law victims or their families can be a civil party or 'partie civile' to criminal proceedings. After ten years of legal process and incessant battling by the families against the prosecution authorities so that a trial could take place and that those responsible be punished, the justice system concluded the affair with a glacial “move on, there's nothing to see here” after simply accepting the word of police officers.

Does one also have to cite the new trial in the Outreau affair, another staggering illustration of the poor state of the justice system, which is being held this month at Rennes in western France because of judicial juggling which heaps catastrophe on top of catastrophe? Must one recall, too, the stubbornness of the prosecution authorities in Paris over the three people under investigation in the Tarnac affair, the obstinacy of its magistrates who, despite the police fiasco in the case, are demanding a criminal trial for alleged terrorism, basing themselves principally on the contents of a book? And is it also necessary to go through the many prison sentences meted out to activists who protested against the Sivens dam in south-west France, and at Nantes and at Toulouse in recent months?

The Bettencourt affair incorporates all the malfunctions, the pettiness, the dependence upon the executive and the conservatism seen in those cases. However, a common theme emerges from all of them: that of crushing the weak and saving the powerful. The Bettencourt affair started in spite of efforts to stifle it by a prosecutor under the orders of the Sarkozy government: Philippe Courroye. He was then prosecutor at Nanterre, west of Paris, having been nominated to this position in March 2007 against the advice of the judges' body the Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature. Philippe Courroye used all the procedural weapons at his disposal to keep this unexploded bomb under lock and key and out of harm's way. It was only Mediapart's revelations in June 2010, of the secret recordings made by Liliane Bettencourt's butler, Pascal Bonnefoy, that allowed details of the political stakes of this unprecedented scandal to emerge.

There then began a series of wide-ranging procedural battles accompanied by various pressures and manoeuvrings. From this long saga let us simply recall two episodes. The first is the shattered life of Claire Thibout, Liliane Bettencourt's accountant. For having talked to Mediapart and then the justice system about illegal political funding, this whistleblower has been methodically cut to shreds. Today she finds herself under formal investigation for “false testimony and untruthful statements” in proceedings that were launched by François-Marie Banier and Patrice de Maistre, both jailed on Thursday for their role in the Bettencourt affair.

Unprecedented censorship

Enlargement : Illustration 2

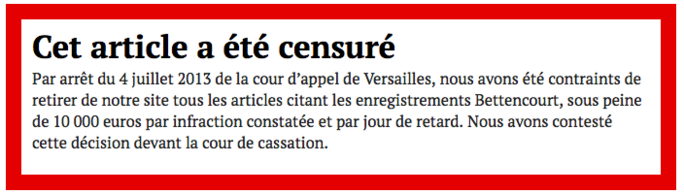

The second episode is no less important as it concerns freedom of information and the citizens' right to know. It involves the censorship of more than 70 Mediapart articles (see the list here) that was ordered by the court of appeal in Versailles. In a judgement on July 4th, 2013, the judges of this august court ordered us to withdraw from our site all the articles that quoted from the Bettencourt recordings, or face a fine of 10,000 euros per offence, per day.

We have since taken the case to the European Court of Human Rights in a bid to overturn this freedom-killing decision that put in place censorship on a scale never before seen under France's Fifth Republic. Everyone could see the absurdity of this judgement during the Bettencourt court proceedings. The recordings were used at length and in detail during the hearings, and could even be quoted from in reports of those proceedings. Fundamental principles - the freedom of information - were put at risk to help organise the defence of powerful people. And the justice system yielded to this masquerade.

— Eric Woerth (@ericwoerth) May 28, 2015

Éric Woerth will therefore do the rounds of the television studios to boast about how he has restored his honour. The acquittal will be akin to an absolution as no one will spend time reading the full judgement, even though it is extremely instructive. Through this former budget minister, treasurer of the right-wing UMP and loyal Sarkozy supporter an entire system has been validated, with the fate of the individual himself of no great importance. The Sarkozy system, which today is under formal judicial investigation (in total some 25 people close to the former president are under investigation in various affairs), will use this outcome to claim a little louder that it has been unfairly attacked, as it did so ceaselessly in 2010 and 2011. There is no doubt, either, that Nicolas Sarkozy himself, still encircled by numerous other judicial affairs, will brandish this acquittal like a hunting trophy at his UMP party's extraordinary conference on Saturday May 30th.

The chatter will make a lot of noise. But this political din will scarcely mask the profound crisis of a judicial institution in complete disarray and which the government cares little about except when it is a question of trimming its budget. Of all the reforms promised by François Hollande for a justice system that is first of all independent, and then modernised and attentive to the citizens' needs, not a single one has been carried out. At her ministry at Place Vendôme in Paris, the justice minister Christiane Taubira presides over successive crises in her private office (three chiefs of staff in three years). Meanwhile nothing changes. Meanwhile nothing is done to raise up and reinforce the rule of law in this country.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be read here.

English version by Michael Streeter