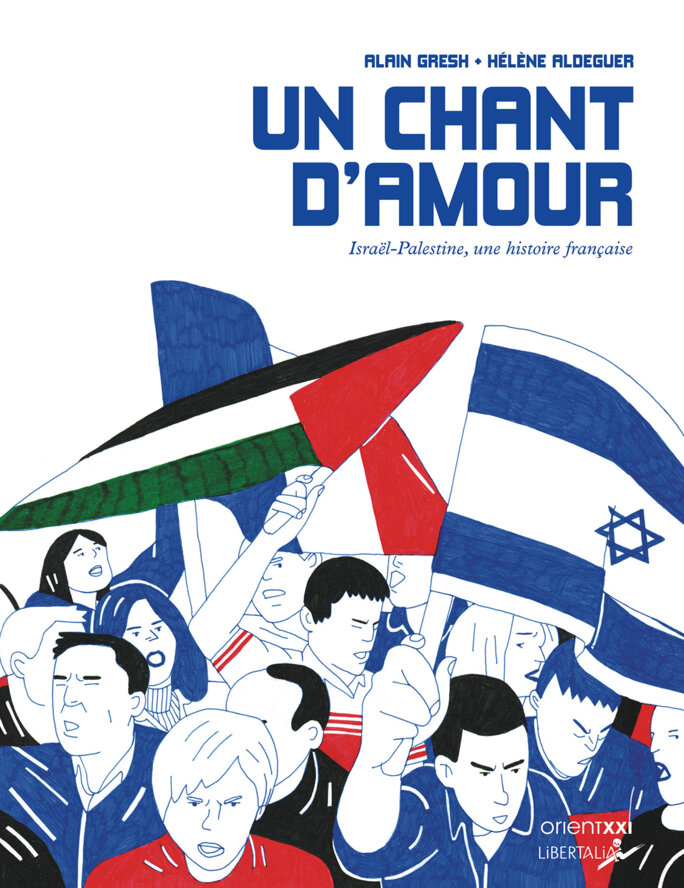

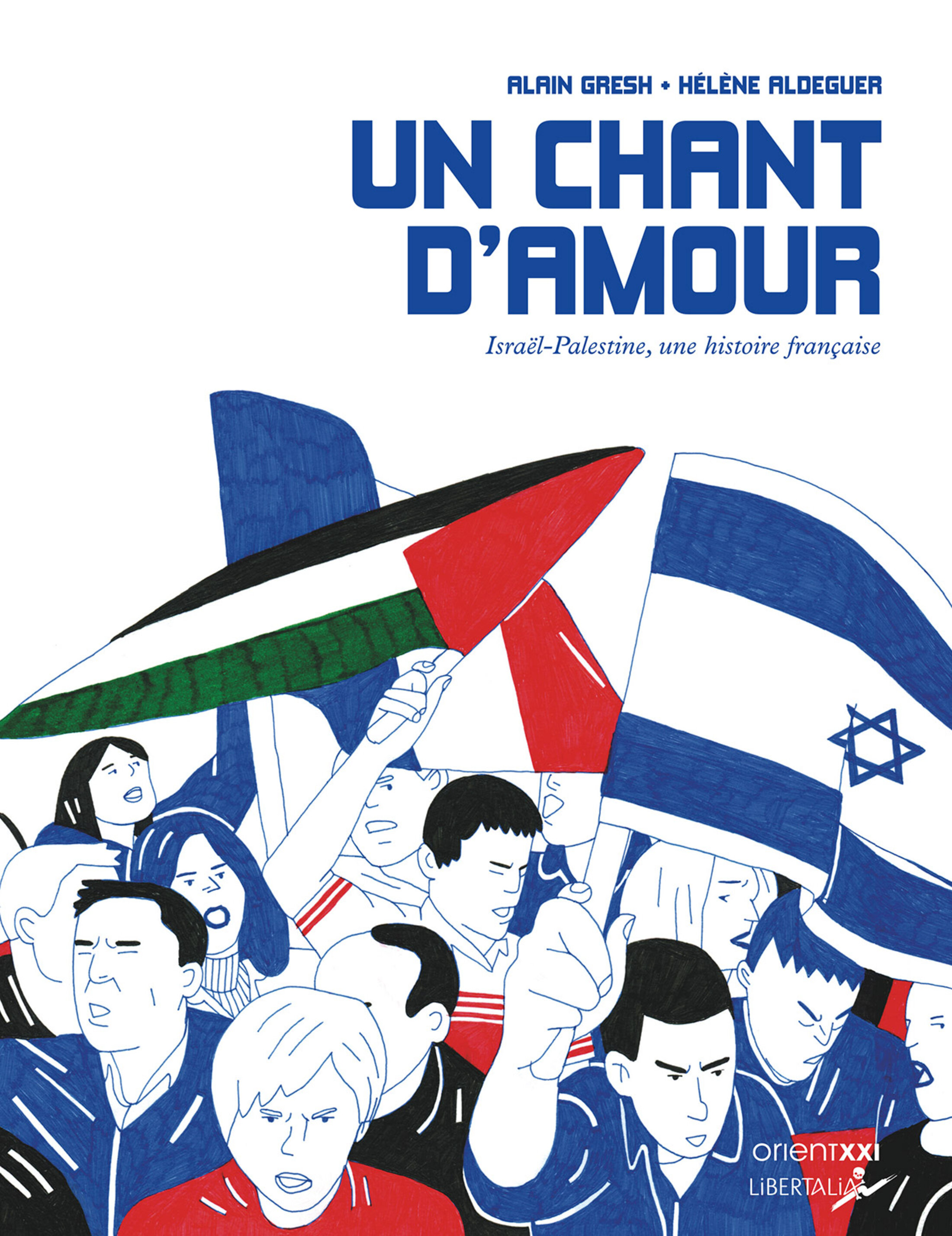

French journalist Alain Gresh is a veteran specialist in Middle East affairs, a former editor of the monthly review Le Monde diplomatique and now editor-in-chief of Orient XXI, an online magazine focussing on the Arab world. He is the author of a graphic book, illustrated by Hélène Aldeguer, about the history of France’s diplomatic strategy towards the Israel-Palestine conflict over the past 50 years.

First published in 2017 and entitled Un chant d’amour. Israël-Palestine, une histoire française (A love song. Israel-Palestine, a French story), it has been updated for its republication this month by Les éditions Libertalia, a timely release amid the spiralling crisis in the Middle East. Gresh recounts, in detail and with insightful anecdotes, the evolution of France’s independent, non-aligned approach towards Arab countries and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as initiated by Charles de Gaulle, and what he calls “a silent turning point” after which, he argues, French diplomatic clout in the region has become significantly weakened.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the interview below with Mediapart’s international affairs editor François Bougon, Gresh outlines the history of France’s rise and decline on the scene of Middle East politics, its realignment with the US approach to the region after decades as an independent broker, and warns of a now widening gulf between France and the Arab world.

-------------------------

Mediapart: What is the sense of the “love story” you refer to in the title of your book?

Alain Gresh: During a visit to Israel by [then French president] François Hollande in 2013, [Israeli] prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu organised a private dinner which was filmed and circulated without the knowledge of the French president. A local artist had struck up the song by Mike Brant [the late Israeli singer songwriter who found fame in France] Laisse-moi t’aimer (‘Let me love you’). Benjamin Netanyahu then asked the French president to break into song. Hollande refused, explaining that he was a bad singer but that, if he could have, he would sing “a love song, a love song for Israel and its leaders”.

For me, those words by a French socialist president illustrate the special relationship that was established between France and Israel, to such a degree that a socialist president could express himself in that way to one of the most rightwing prime ministers of his country, a prime minister who obstinately refuses any idea of a Palestinian state which Paris, nevertheless, is in favour of. It seemed to me representative of the evolution of French policy over some 15 years, what I call in our graphic account “a silent turning point” with regard to France’s traditional policy.

Mediapart: We’ll come back to that but, firstly, why had it taken until March 3rd 1982 for the first visit by a French president to Israel, a state created 34 years earlier?

AG: One must wind back to June 1967. At the time, general [Charles] de Gaulle explained that he would condemn the country which would start the war, and so he went on to condemn Israel. From that moment, French policy was founded on the idea that one couldn’t have “normal” relations with Israel as long as it continued to occupy Arab territories – the Sinai and the Golan, but also the West Bank and Gaza. In October 1973, when the Egyptian and Syrian armies attacked Israel, the French foreign affairs minister, Michel Jobert, declared: “Does trying to step back into one’s home constitute an aggression?” One understands that during all this period, French-Israeli relations were tense.

François Mitterrand, was instead rather Israelophile, alive to Jewish culture, a reader of the Bible. He tried in a certain way to shift this [previous] policy. But in fact, despite a trip made in March 1982, he found himself faced with [Israeli] prime minister Menachem Begin, an intransigent man of the Right, who refused to budge. There we find in Mitterrand this idea, which we would subsequently see in other French leaders, according to which it suffices to be more “understanding” towards the Israelis in order to succeed in changing their policies, notably those concerning the Palestinians.

In 1982, not only did François Mitterrand obtain nothing in exchange for his visit, but, a few months later, the Israelis launched Operation Peace for Galilee [the 1982 Lebanon War] and invaded Lebanon, mounting the siege of Beirut and hunting Yasser Arafat.

Nevertheless, even if there were changes since de Gaulle, French diplomacy kept to the same line: it is not possible to have normal relations with a state that occupies Arab territories and which does not want to settle the Palestinian issue. That fundamental line of French diplomacy would change with the arrival of [Nicolas] Sarkozy at the Élysée [in presidential elections] in 2007.

Mediapart: Since when has the Israeli-Palestinian question been an issue in [French] internal politics?

AG: One must go back to well before 1967. Over the period 1947-1949, a consensus emerged from within the whole of the French political class – which can seem incredible – in favour of the creation of the state of Israel. Jewish emigrants left French ports with the support of the government. This [political] alliance spanned from the Communist Party – the Soviet Union supported the creation of the state of Israel – to the republican [mainstream] Right. Very few discordant voices were raised to point out that Palestinians lived on the spot and that this creation [of the state of Israel] led to the expulsion and departure of 800,000 Palestinians.

At the time of the Suez Canal crisis in 1956, when the French, British and Israelis were allied together to attack Egypt after it decided to nationalise the canal company, the divides were different, because the Communist Party opposed the [military] intervention decided by the socialists with the support of the Right. But, apart from the CP, support for Israel was very wide.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But it was really as of 1967 that the question would become a red-hot domestic issue. In France there is both a large Jewish community, which was made bigger by the arrival of the pieds-noirs of Algeria [editor’s note, the settlers who fled the North African country during and after the Algerian war of independence], and a large Muslim community, for reasons of our colonial past. There is also the will of general de Gaulle to take a major Arab and Mediterranean policy stand at the end of the Algerian war. He began a political rapprochement with numerous Arab countries, like Egypt and Syria. That strategy would be continued by his successors, [Georges] Pompidou and [Valérie] Giscard d’Estaing. Nevertheless, upon his arrival as president in 1974, the latter, who was not from the Gaullist party, was regarded as pro-Israeli.

But Giscard would accept the opening of an office [in France] of the Palestine Liberation Organisation. In the book, we illustrated this anecdote: it was when shaving in front of the mirror in his bathroom that the prime minister at the time, Jacques Chirac, learnt of Giscard d’Estaing’s decision, on the radio. He was mad with anger, hostile at the time to such relations with the PLO and not at all pro-Palestinian.

This French policy was conveyed in the Venice Declaration of June 1980. The French president [Giscard d’Estaing] rallied together the nine members of the European Economic Community [editor’s note, the EEC, predecessor of the European Union] around a text which set out the bases of what should be a political solution – the right of all states in the region, including Israel, to live in peace and security, the right of Palestinians to self-determination, and the necessity to negotiate with the PLO.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

This political line, strongly criticised by Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, who claimed that France wanted to negotiate with “the Arab Nazis”, and by the Americans, who denounced the PLO as being a “terrorist organisation”, would triumph in the end with the signing on September 13th 1993 of the Oslo Accords between the Israeli government and the PLO.

During all this period, which spans from 1967 to the 2000s, French leaders are convinced that an independent voice must be made heard, and that they promote the only realist solution. France and Europe will succeed in changing the order of things. A whole series of events would make the PLO into a legitimate interlocutor. Already recognised by the USSR and its allies, by the non-aligned, the PLO would [also] be so by Europe, which would contribute to reinforcing its choice of a political solution. That is how the conditions for the opening of negotiations with Israel, and the signing of the Oslo Accords, were created.

Mediapart: You underline that the Americans reaped the media benefits; there was the photo of the handshake between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat at the White House, under the gaze of Bill Clinton, whereas they had not done very much.

AG: Not only had the United States not done very much, but when prime minister Rabin informed Clinton about the secret discussions going on with the PLO, the American president advised him against continuing with them. Finally, the United States cashed in on the process. From then on, we enter into an ‘intermediary period’ during which France still had a role, but a declining one.

Both the Israelis and the Palestinians considered that the Unites States is the essential arbiter, and the role of France and the European Union is limited to financing the Palestinian Authority. And during this post-Oslo period, which coincides also with the end of the Cold War, the idea that the problems of the world will be solved was dominant, and Europe [the EU] was essentially preoccupied by its enlargement.

Mediapart: So 1993 marked the beginning of the effacement of French diplomacy?

AG: Yes, Oslo is one of the elements that will accelerate this effacement. Jacques Chirac attempted, for a while, to weigh on the negotiations. But if one follows the history of these negotiations between Israel and the PLO, what is striking is that the Americans are on the Israeli side and that the Europeans, because they want to see a success and know that the Israelis would not give way, put pressure on the weak side, the Palestinians, to make more concessions, emptying the accords of all substance.

In the end, that would provoke a growing opposition in Palestine and culminate with the Second Intifada [Palestinian uprising] in 2000. The Palestinian Authority, which had bet on the creation of a Palestinian state through negotiation, failed, and it is Hamas that would reap the benefits of that failure.

Mediapart: What are the policies led by Emmanuel Macron?

AG: He is following the policy inaugurated by Nicolas Sarkozy and followed up by François Hollande. That is what I describe as a “silent turning point”, because it is a true political change but which is not acknowledged – shameful, I would say. Successive French governments claim to remain favourable to a two-state solution but do nothing to make it happen, which would require bringing pressure on the side that refuses this solution: Israel. Whereas, on the contrary, France develops bilateral relations with Israel at an unprecedented level, supports the exceptional status that Israel has with the European Union – privileges that no other non-European country has, in terms of trade rights, of scientific cooperation, of strategic consultation and so on.

The continuation of [the Israeli] settlements does nothing to impede this support, even if Paris regularly publishes statements to condemn it. The Israeli authorities pay hardly any attention to these declarations, in as far as bilateral relations between France and Israel, and with the European Union, are not impacted.

Another reason contributing to this change in French policy is the place taken up by “the war on terrorism” since the September 11th 2001 attacks on American soil. There came about a vision of the world in which the West, of which France is a part, faces a worldwide Islamist threat, and in this context Israel is an ally. All the more so in that Hamas has gained an increasingly important weight over the past 20 years.

It is not understood that the weight of Hamas is the result of the failure of the Palestinian Authority to create a Palestinian state. It is the failure of the Oslo Accords, on which the Palestinian Authority and Palestinian moderates had placed all their bets; which is why, as in any country, people transferred votes to their opponents – Hamas. That is how they won the 2006 elections.

Mediapart: Do you see in the French political field individuals who continue, despite everything, to try and carry this independent voice that you speak of?

AG: There are not many remaining at a political level. They are mostly the “old” elements, like Dominique de Villepin [editor’s note, a former French prime minister and who notably, when foreign minister in 2003, gave a speech at the UN setting out French opposition to the US-led invasion of Iraq]. This tradition, not only on the Israeli-Palestinian question, of an independent French policy with regard to the United States has largely disappeared. It has disappeared both from the senior branches of the French administration and from political parties.

Dissonant voices are rather presented among a small section of the Left and also the far-left, but are rare and often “cautious” because today it is easy to disqualify someone from public debate by accusing them of supporting terrorism, or of being anti-Semitic. One has only to listen to the agitation in the media over each statement emitting doubts about Israeli policies towards Gaza. The media have an aggressiveness that I had not seen since a long time, undoubtedly since the 1967 war.

There is, finally, one aspect that I would like to insist upon. It is the gulf that has widened between France and the Arab world with the occasion of this crisis. France has never been so criticised [in the Arab world] by all the political circles, every current, from the Islamists to the liberals and including the Left. There is unanimity.

Take Tunisia, where for the past ten years the political scene is very divided over the Islamists, about their place and so on. There exists within it today a large front of support of the Palestinians and to denounce, with virulence, French policies. I don’t know if our leaders are conscious of this. France will pay a heavy price for it, in the short- and medium-term across all the Middle East and the Maghreb. Following the French fiasco in Africa, that should preoccupy our leaders.

-------------------------

- The original text of this interview, held in French, can be found here.

English version, lightly abridged, by Graham Tearse