French experts and researchers have no say in the running of the top-level biosafety laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China despite the fact that France helped build the facility and that Paris and Beijing signed an agreement on future cooperation and collaboration, a Mediapart investigation can reveal.

The French-designed laboratory, which is a level 4 biosafety facility equipped to handle Class 4 pathogens (P4) - which include deadly viruses such as Ebola – was opened in 2017 and plans were set in place for continued French involvement in the running of the facility, the first of its type in Asia

The then French prime minister, Bernard Cazeneuve, himself spoke glowingly of the project when on February 23rd 2017 he inaugurated the laboratory in Wuhan. “Ladies and gentlemen, this laboratory that we have built together will be the spearhead of our fight against emerging diseases,” he declared. “It will increase considerably China's ability to carry out cutting edge research and to react effectively to the emergence of infectious diseases which threaten the people of the entire globe.”

But three years later a new Coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 - which causes the disease Covid-19 - emerged in this same city and then spread like wildfire around the world, leaving scientists still unsure to this day as to its precise origins.

The “spearhead” proclaimed by Bernard Cazeneuve had not lived up to its promise. Moreover, since its inauguration in 2017 France has been kept at arm's length from the operations of the Wuhan P4 facility even though Paris was heavily involved in delivering the project to China.

A P4 or biosafety 4 laboratory is a considerable high-tech achievement which requires the maximum level of safety and security. These are the places where researchers kitted out in biohazard suits study micro-organisms from level 4 pathogens that have a high rate of mortality, are easily transmitted and for which there is no current treatment.

Yet contrary to the commitments that had been given, not a single French researcher occupies the 50 or so positions that had initially been earmarked for them at the Wuhan facility. According to Mediapart's investigation, not only was this failure foreseeable, senior French health and defence officials did indeed alert the government in Paris about the risks inherent in transferring this form of technology to China. In particular they warned that China would not abide by the guarantees written into the cooperation agreement for the project signed back in 2004 and which dealt with technical and legal safety standards and the monitoring of the facility.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Indeed, over the years many concerns were expressed about the project. The first was that China would effectively copy this laboratory and put it under the control of the People's Liberation Army for military use. This was the risk of what is known as 'proliferation'.

There were also scientific concerns. Would the P4 lab be a genuine vehicle for mutual cooperation or would it shut itself off under pressure from the Chinese state? But there were security concerns, too, including huge uncertainty around the construction of the facility: would the Chinese health authorities adapt to international standards of security and safety? Could France guarantee the trustworthiness of the facility if the operating rules were not the same as elsewhere and there was a lack of training?

Despite all these fears the project became a top priority for France in its relations with China after President Jacques Chirac gave the green light to it in 2004. But above all it became the pet project of French billionaire businessman and politician Alain Mérieux, president of the Institut Mérieux which is the parent company of the bioMérieux group. The P4 laboratory at Wuhan is in fact a replica of the P4 lab built at Lyon in eastern France by the Mérieux Foundation and which is now run by INSERM, France's Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale ('French National Institute of Health and Medical Research').

In 2008 Mérieux was appointed as co-president of the steering committee overseeing the Franco-Chinese agreement and for fifteen years he effectively became the spokesperson for the Chinese authorities' desire for France to turn a blind eye as much as possible to the legal guarantees that it had set out, and simply get on with building the laboratory.

According to one senior civil servant spoken to by Mediapart, the Chinese pressure on France continued even after the end of the construction work in 2015; Beijing wanted a “transfer of pathogenic [virus] strains” from the Jean Mérieux P4 facility in Lyon to the lab at Wuhan. Both the health and defence authorities in France opposed the move, as they believed that Paris had “completely lost control” over the laboratory after the facility was given its certification solely by the Chinese authorities.

The activities of the P4 lab at Wuhan, which is linked by a walkway at the Institute of Virology to the P3 laboratory which studies coronaviruses, are today the subject of international scrutiny. Two diplomatic cables from the United States Embassy in Beijing, which were revealed in April 2020 by the Washington Post columnist Jogh Rogin, show that there had been contacts two years ago between an American scientific adviser and the heads of the Institute of Virology. According to a cable sent on January 19th 2018 diplomats warned that the “new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory”.

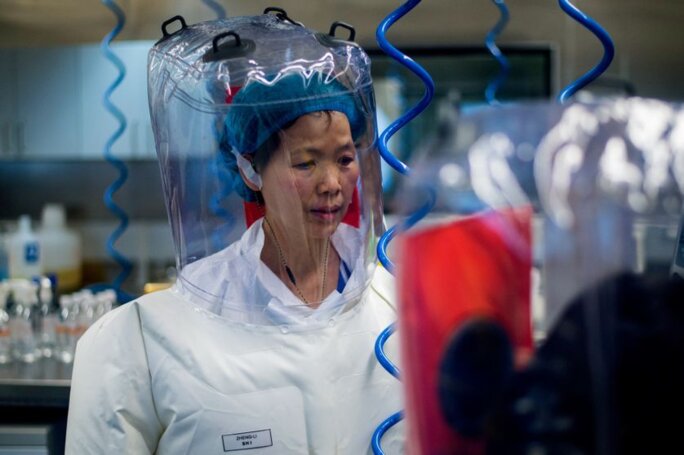

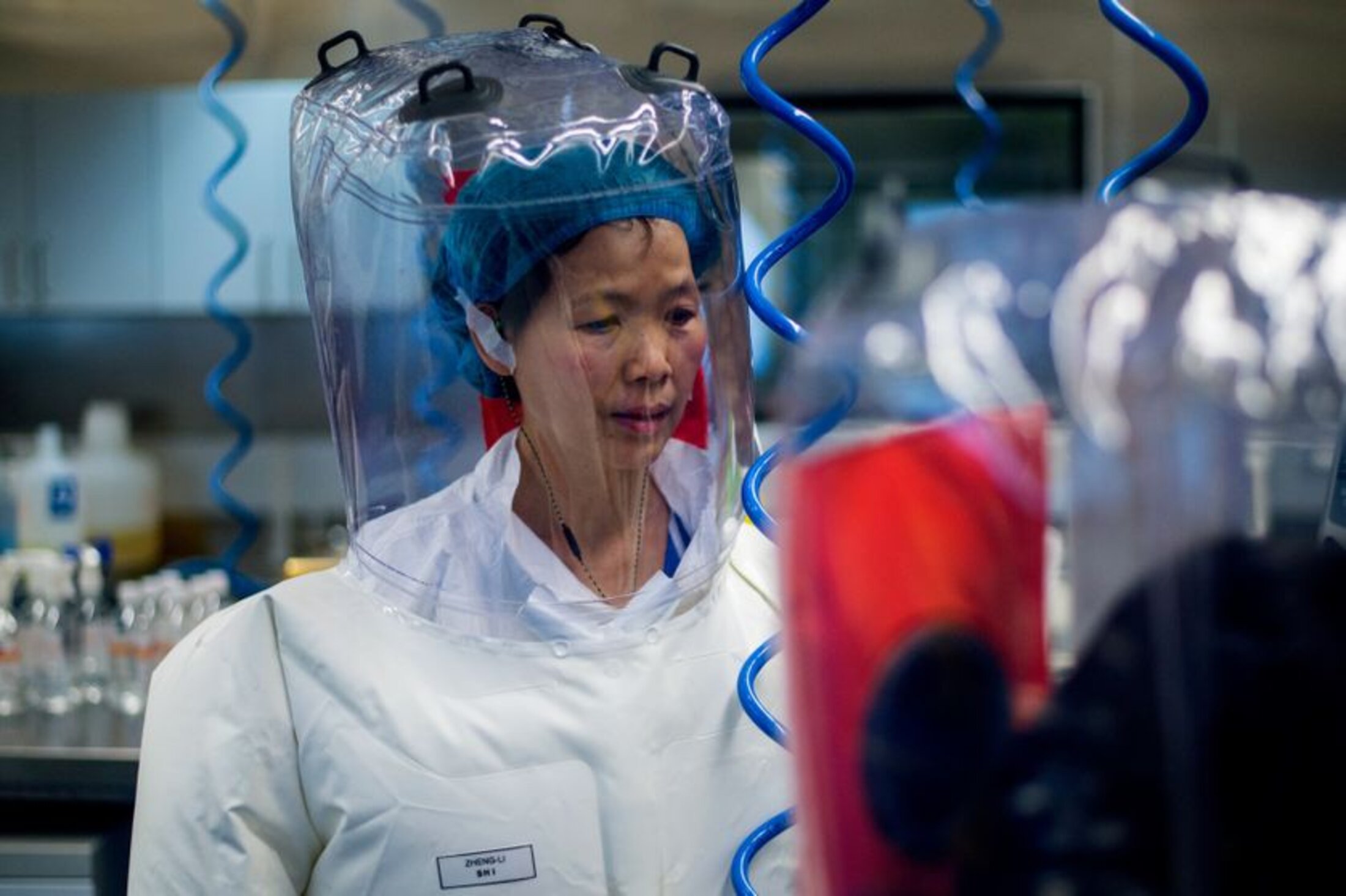

That is clearly insufficient evidence to back the theory that there could have been an accidental leak from the Franco-Chinese P4 laboratory or the four P3 virology laboratories in the city which then led to the pandemic. But the fear of a possible error did initially worry some researchers at Wuhan too. Shi Zhengli, who was trained at the P4 laboratory in Lyon, and who is an expert on coronaviruses having co-authored five articles on the subject for Nature magazine, is the director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). At the end of February she told Scientific American that when it was announced that a new coronavirus has been discovered in patients in Wuhan, she had checked samples from her lab to see if they resembled the new virus and also went back over lab records to see if there could have been any mistakes in the disposal of samples. Fortunately, she said, none of the genome sequences of the new virus matched those of viruses her team had taken as samples from bat caves. “That really took a load off my mind,” she told the magazine. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But though scientists have discounted the possibility that this new deadly virus was created in a laboratory – a conspiracy theory put forward by President Donald Trump on April 20th 2020 – there is still considerable international pressure for clarification about the emergence of the virus in Wuhan and also over Beijing's handling of the crisis.

Wuhan's 'wet market' had originally been singled out as the likely origin for the virus, but this appears no longer to be the case after it emerged that a patient who had no contact with the market had previously succumbed to the disease.

On Saturday May 23rd Yanyi Wang, the director the Wuhan Institute of Virology, to which the P4 laboratory belongs, stated that a “clinical sample” of the SARS-CoV-2 virus had been obtained for analysis on December 30th. She told CGTN, an English-language Chinese state television network, that the institute did not have “any knowledge before that” of the virus. “We had [never] come across, researched or kept the virus,” she said. She continued: “In fact, like everyone else, we didn't even know about the existence of the virus, so how could it be leaked from our lab when we didn't have it?”

At the virtual summit of the World Health Organisation (WHO) held on May 18th, China finally accepted the principle of an international inquiry into the origin of the new coronavirus, even though the parameters of any such investigation are still not clear.

Here Mediapart retraces the steps of the high-risk agreement between France and China to build the new P4 facility in Wuhan.

- The Mérieux project approved despite opposition from defence officials

“I want the truth to be established about what really happened in this laboratory,” former prime minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin told Mediapart. “I'm certain that, along with President Jacques Chirac and Alain Mérieux, we acted in the interests of France as, I think, did the other governments that followed.” While he points out that “four presidents, seven prime ministers, around twenty governments [editor's note, meaning new or reshuffled French governments over that period] and eight ambassadors have shared this project” it was Raffarin as prime minister who was one of the first French politicians to approve the future P4 laboratory project at Wuhan.

Back in April 2003 Jean-Pierre Raffarin had decided to go ahead with a trip to Beijing despite the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic that was raging at the time, and swiftly took the first steps towards “scientific cooperation” with China to fight “against pandemics”. This resulted in the signing of two agreements by President Chirac and his Chinese counterpart President Hu Jintao, on January 27th and October 9th 2004. It was the second agreement which formalised the “authorization to transfer the constituent parts and know-how needed for the development of a high-security facility or facilities, in particular help in developing a level 4 biological security laboratory (NSBC4) at the Wuhan Institute of Virology”. It was accompanied by a number of conditions.

'The Chinese army is clearly interested in P4 labs'

“On the domestic front some legitimate reservations were, as always, put forward in the preliminary stage,” said Jean-Pierre Raffarin, “but the scientific community – INSERM, the Pasteur Institute, the P4 [lab] at Lyon and Alain Mérieux – produced arguments to resolve these and convince the president and the six ministers concerned. I don't recall problems in the inter-ministerial meetings.”

In reality Alain Mérieux had campaigned in favour of the Chinese request for a P4 laboratory since the middle of the 1990s. “The defence world had extreme reservations,” a senior national security official told Mediapart. “The risks linked to secret biological projects by Russia and China were constantly flagged by the intelligence services. But a pro-Chinese steamroller was trying to make one believe that it was a great project. During the period of co-habitation [editor's note, from 1997 to 2002 when there was a government led by a socialist prime minister, Lionel Jospin, under a centre-right president, Jacques Chirac] we had developed a strategy for a stop mechanism, by requiring guarantees in the proposed agreements that kept coming.”

“The government didn't want to obstruct China's request,” said the senior civil servant. As the administration itself was split, it was the Mérieux faction which ended up winning. “And a large number of those guarantees were thrown in the bin,” said the official. “We all knew there was a risk. The question was: is this risk worth the trouble? And also, could we monitor the facility or not? The majority of experts judged, rightly, that we couldn't monitor anything at all. There was considerable naivety in relation to China.”

Alain Mérieux, now aged 81, who inherited the institute funded by his grandfather Marcel in 1897 and who is now ranked as the sixteenth wealthiest person in France, is certainly not naïve. In the past he has described how he first developed links with China via his father-in-law, who was in the car industry and who in the 1960s was already doing business with Beijing. But it was his involvement in Jacques Chirac's Gaullist RPR party which put him in touch with Chinese party officials.

“During my political career with Jacques Chirac I was called on to become first vice-president of the Rhône-Alpes region [of south-east France],” he told the website Chine-Info in April 2019. It was a position he held from 1986 to 1998. “And in 1986, when the region's president signed an agreement with the city council of Shanghai, whose mayor was Mr Jiang Zemin [editor's note, who was later General Secretary of the Communist Party of China after the repression in Tienanmen Square in 1989 until 2002 and President of the People's Republic of China from 1993 to 2003], I was put in charge of relations with Shanghai. This responsibility meant I went to China twice a year, for twelve years, with my university colleagues from Lyon and Grenoble.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Via his public relations company Image 7, Alain Mérieux said that having “ended his activities” on the Franco-Chinese committee on emerging diseases in January 2015, he would not reply to Mediapart's questions about his involvement in getting the P4 laboratory in Wuhan built.

The businessman pointed out that he had “only taken part in a personal capacity in the running of this committee” - whose Chinese co-president was his friend, the former Chinese health minister Chen Zhu – the aim of which was to “help the creation of a P4 laboratory”. Moreover, his presence on the committee did not involve his companies, he insisted. “Neither the Institute Mérieux, nor the companies, nor the Mérieux Foundation took part in the creation of the P4 laboratory at Wuhan and they are not involved in its management,” Mérieux said via the PR agency.

When talking to Chine-Info in 20-19, however, Alain Mérieux had spoken about a “very long collaboration” with the Chinese Ministry of Health and some joint “efforts” which “culminated with the handing over of the keys to the P4 laboratory to the Chinese authorities”. He said: “The P4 laboratory is a major asset because first of all it is the only high-security laboratory in Asia. … it was Jacques Chirac's wish to design and create it when he was in China during the SARS epidemic. When you create something there are always people against it. So obviously some countries who were not that enthusiastic about seeing this laboratory in China had to be convinced.”

When questioned about the risk of military use of this cutting edge technology by China, Mérieux replied: “It all depends on what one does with it and whose hands it is in.”

“Even if one can understand the medical logic after the SARS epidemic, the P4 lab raises questions,” Valérie Niquet, senior research fellow at the strategic research foundation the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique (FRS) and a specialist on Asia, told Mediapart. “You have to ask what degree of cooperation is possible in some sensitive technologies with a country that integrates civil and military industries. The Chinese army is clearly interested in P4 labs. The French security authorities were reticent about supplying this type of lab to China.”

- Mérieux threatens to resign and flags the risk of an accident

The 2004 agreement contained sections that were immediately implemented: the delivery of four mobile P3 laboratories and the setting up of a Pasteur Institute in Shanghai under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Science. The arrangements to build the P4 laboratory were also set in motion. Responsibility for the design of the lab was given to the Lyon architect firm Tourret Jonery who built the Jean Mérieux P4 lab in Lyon. A Chinese firm, IPPR Engineering International, was hired to do the main building work, while a specialist biosecurity French firm Clima Plus took care of the bio-containment at the facility.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Enlargement : Illustration 5

But some of the written guarantees obtained by French defence officials about the P4 were to prove problematic. In the intergovernmental document signed in 2004 China had committed to “enhance its national legislation and regulation, drawing on French regulations” concerning the “authorisation and traceability in relation to the act of possessing, transferring, transporting, importing and exporting certain agents that cause infectious diseases, pathogenic microorganisms and toxins”. These safeguards also included an “inventory of [virus] strains and their inspection”.

In 2006 an addendum to the agreement once again highlighted the “need to bring into line with international norms, recommendations and best practice those Chinese standards” which “will need to apply to the future NSB4 Wuhan laboratory facility” in terms of biosecurity. The Chinese agreed to start the “transposition of international norms into the body of Chinese law” with the help of the French health product safety agency the Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (AFSSAPS) – now the ANSM – and AFNOR, the Association Française de Normalisation, which oversee the standardisation of products.

'There was a kind of plot, a lobby who wanted to stop us building this lab'

However, in 2008 Alain Mérieux took over the commands of the French side of the project and replaced Christian Bréchot, the former boss of INSERM, as the co-president of the Franco-Chinese committee. Bréchot was instead appointed as vice-president of the Institut Mérieux and to the medical and scientific board of BioMérieux. Mérieux had noticed that the Chinese did not like the way French administrative bodies worked and they were becoming impatient.

Indeed, the delay in laying the first stone for the P4 lab – which the Chinese hoped would occur in 2009 – became a point of conflict, leading Alain Mérieux to contact the French government.

According to a note headed “Some points of reply to the letters from Mr Alain Mérieux” written at the start of 2010 by senior Ministry of Foreign Affairs official Hélène Duchêne, Alain Mérieux had attacked the “incompetence” of French civil servants. And he had threatened to resign from the co-presidency of the committee, brandishing the risk of a “serious biological accident”.

From reading the civil servant's response, it appears that Mérieux's accusations concerned, in no particular order, “some acknowledged errors and incompetence coming from the French side”, an “incomplete and unsuitable proposal by AFNOR”, the “poor ordering in terms of priority of the training proposed to the P4's Chinese personnel” and the “still incomplete analysis of the Chinese documentation in terms of biological safety and security”.

Mérieux also considered that the “technical proposals and documents sent to the Chinese side” had been “approved by French personnel with no recognised expertise in the areas in question”.

Finally, the businessman listed some “serious risks” (see document below) linked to the project: “A refusal to certify the P4 laboratory in Wuhan by the competent Chinese authority and the WHO. In case of certification and thus putting the laboratory into service, the danger of a serious biological accident. In both situations there will be questions over France's responsibility.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

In her suggested reply Hélène Duchêne, who was then in charge of overseas development and who is today the ministry's director general of administration, broadly accepted the complaints made by Alain Mérieux and the Chinese.

“Mr Alain Merieux's note to a large extent reflects the reality of the situation,” she wrote. “The failures and the incompetence raised and already reported by staff [editor's note, diplomatic staff] have also been reported by the Chinese side. Certain French participants who have been involved for too long in this dossier are to a large extent contributing to slowing down the project. The Chinese side is still showing a desire to work with France. … The two agencies could be reminded once again, at the highest level, of the political importance of the dossier. In fact they tend to behave like 'free spirits' and not as a source of cooperation.”

Contacted by Mediapart, Bernard Kouchner, who was then France's foreign minster, said that while he was not closely involved in this project with China, he was “strongly in favour” of it. This was despite opposition which “revolved around the Ministry of Defence” and the “DGSE [editor's note, France's external intelligence agency] who said to us, in essence, that you're going to introduce the worm into the fruit, and that a lot of virus is going to come our way”.

Kouchner, a co-founder of the charity Médecins Sans Frontières, said: “On each occasion I gave a positive opinion but it was Alain [editor's note, Mérieux] and not me who was the linchpin of this construction.”

“There was a kind of plot, a lobby who wanted to stop us building this lab,” said the former foreign minister. “It was all a bit vague. It needed a decision and what the director of development [editor's note, Hélène Duchêne] wrote was correct. It needed a decision. And it was a decision that [President] Nicolas Sarkozy took.”

Reassured by this at the time, Alain Mérieux did not resign. And he managed to get the coordinator of the Franco-Chinese committee, who was a scientist, replaced by Jean-Michel Hubert, a top civil servant who had been secretary general of the city authorities in Paris when Jacques Chirac was the capital's mayor. A number of civil servants also left. Mérieux declined to comment to Mediapart about his note to the French government and its aftermath.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The minister of health at the time, Roselyne Bachelot, confirmed to Mediapart that she had “received a warning letter from Mr Mérieux”. She said: “To stop any drift and to ensure perfect collaboration, Mr Hubert was then appointed to deal with the implementation of the 2004 agreement, in fact to take control of the case and ensure close monitoring of those involved (Chinese as much as French...).”

One of the civil servants targeted by Alain Mérieux at the time told Mediapart: “We were under great pressure. It was a very tough period. It was we who spoke about the dangers. We had been asked to upgrade the regulatory section and the Chinese technical standards. The vast majority of the Chinese technical norms were described as obligatory but even so that didn't guarantee more safety.”

The civil servant continued: “What do you do when there is a serious accident in a country with its own norms? The upgrading of these texts involved all safety and security criteria. Unlike us the Chinese did not distinguish between the notion of safety – in case of accident – and that of biological security – in case of a malicious act. For them it was the same thing, for us they are two complementary domains. We also had to take into account the effectiveness of texts and laws. Who applies them and how? Is there a system of liability, of sanctions, and what are they?”

Among all the tough issues, the updating of the contract's legal safeguards was a real headache for those involved. “When we asked what we were going to do if the Chinese didn't comply, our managers acknowledged that they had nothing to put on the table,” recalls one civil servant involved. “We were supposed to implement the 2004 agreement, but they didn't leave us with much. The P4 had to progress. We didn't know what was at stake. Why so insistent? What was the quid pro quo?”

'The Pasteur Institute never knew what went on at the P4 in Wuhan after it was built'

“Agreeing to cooperation in these domains meant thinking that you could control it,” said researcher Valérie Niquet. “Yet China is a country which doesn't have rules. Thinking you can cooperate with China like a normal country is a mistake, it's not a normal country. And that's linked to the absence of rules.”

- Three ceremonies at the P4 lab, then the French disappear from the scene

There was a series of ceremonies at Wuhan. The formal laying of the first stone on the site took place on June 30th 2011, in the presence of France's junior health minister Nora Berra. Then there was an event to mark the end of work on January 30th, 2015 attended by the minister in charge of relations with Parliament, Jean-Marie Le Guen, who was accompanying the then-prime minister Manuel Valls on a trip to China. Finally, the site was formally opened by prime minister Bernard Cazeneuve at the inauguration on February 23rd 2017 after the laboratory was given its certification by the Chinese regulator.

On each occasion a red ribbon was cut and new promises of future cooperation were pledged. There were smiles for the camera, and even some mannequins, too, placed in certain rooms. The François Hollande presidency from 2012 to 2017 does not seem to have affected the Wuhan project. And yet, despite appearances, the inauguration in February 2017 marked a cut-off point.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

At the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the director of the P4 laboratory at INSERM-Jean Mérieux, Hervé Raoul, still features as a member of the scientific council in his role as 'deputy director' of the scientific council at the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases which is part of the institute. “I accepted the request,” Hervé Raoul told Mediapart, “but I never had any official feedback and to my knowledge this council has never met.”

In May 2017, however, the French scientist announced in INSERM's own journal Science et Santé – in an article headlined 'P4 laboratory at Wuhan: a success for Franco-Chinese cooperation' – that he was expecting to “develop a special working relationship” with the P4 lab in Wuhan. He pointed out that the prime minister at the time had announced that a budget of “one million euros over five years” had been set aside to fund this cooperation which was “due to involve around fifty French scientists, under the aegis and control of INSERM”.

Under the 2004 agreement the Franco-Chinese steering committee was in fact supposed to “take part in defining scientific research programmes to carry out within the remit of the Wuhan P4 laboratory”, to “carry out the monitoring and evaluation of these programmes, ensuring the results are published” and, finally, to give an annual appraisal of the programmes.

According to Hervé Raoul's comments in the INSERM article, putting the Wuhan lab into service was going to be done “progressively”, with the “first research projects on lower-level pathogens”. He explained: “That way we will be sure of good protection of the surroundings outside the laboratory and of the personnel with viruses of lower risk. It's absolutely necessary because the health or socio-economic consequences of a safety failure can be considerable, as we saw in 2007 with the escape of a strain of the foot and mouth virus from an English laboratory.”

But the scientist told Mediapart that “at no point” did he “intervene practically” in the process of starting up the Wuhan laboratory. He recently told Le Monde that the P4 laboratory at Wuhan “seemed rather well-designed … but, to be sure, one would had to have seen it in operational mode. I have visited it several times, but I have not seen it in operation.”

Enlargement : Illustration 9

And Hervé Raoul told Mediapart: “Neither INSERM nor its researchers have seen the activities at the P4 in Wuhan since it was put into operation. While the construction of the Wuhan P4 was indeed in the remit of an intergovernmental agreement between France and the Chinese authorities, INSERM did not take part in the construction of the building nor in its regulatory certification.” He said INSERM's role was limited to the “training of several Chinese researchers as to good working practice inside a P4”. There were six such Chinese researchers trained in 2009, then three others in 2015 and 2016, including the vet for the future animal facility at the lab. Each had three weeks of training inside the P4 laboratory at Lyon.

“The project was supposed to continue after the construction of the laboratory through scientific cooperation,” President Sarkozy's former health minister Roselyne Bachelot said. “History seems to prove that this commitment was not kept or not up to the level that had been announced in the 2004 agreement or by Bernard Cazeneuve during the inauguration,” she said. The ex-minister said that it now had to be established who was responsible for this lack of cooperation. “To know whether the Chinese wanted to exclude us or if the disengagement was the result of misguided efforts by the French or of a lack of political interest in international cooperation on health, which alas certain decisions in the years 2012-2017 [editor's note, the presidency of François Hollande] seem to show...” Roselyne Bachelot added that “to be fair to Marisol Touraine [editor's note, Bachelot's successor as health minister when François Hollande became president] … scientific cooperation also came under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Research [editor's note, part of the ministry of education or higher education] and Mérieux”.

Alain Mérieux left the Franco-Chinese steering committee in January 2015 satisfied that he had accomplished his mission. In a curious turn of phrase, he told Radio France in Beijing that the P4 laboratory at Wuhan was a “very Chinese instrument”. One civil servant told Mediapart: “[Mérieux] resigned when we moved on to the delicate phase of handing over the P4 to the Chinese authorities. France completely lost any control when the certification process reverted to the Chinese.” However, the businessman nonetheless continued to keep a close eye on the project via the Franco-Chinese committee coordinator Jean-Michel Hubert, who gave him personal accounts of his trips to China.

The Chinese government has shown its gratitude to the billionaire businessman. In March 2014, on his first state visit to France, President Xi Jinping went to Lyon to meet Alain Mérieux before he even met the French president. The French businessman also received a high honour from the Chinese authorities, when he was given the 'Reform Friendship Award' in 2018 in recognition of his “commitment to public health in China, particularly the fight against infectious diseases”.

The appointment of Yves Lévy, the chief executive at INSERM, to replace Mérieux in the position of co-president of the steering committee, meanwhile caused some friction. In fact this scientist, who had taken part in most of the official visits to Wuhan, had never been in favour of the project. In particular he refused to agree to new technical support for the laboratory because there was no monitoring, which had become impossible under the new Chinese structure. The inter-ministerial General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN), France's health authorities and INSERM had also rejected the Chinese request to transfer pathogenic virus strains to the laboratory in Wuhan. “It was a constant demand,” said one senior French civil servant.

The Institut Pasteur, for whom the creation of a Chinese office formed part of the 2004 agreement, also emphasised the little information they had about the P4 laboratory at Wuhan. “Pasteur never knew what went on at the P4 in Wuhan after its delivery, because of an absence of joint collaboration and of mutual suspicion,” said a senior figure there.

The proclaimed cooperation between the two countries has reached such a standstill that the last meeting of the Franco-Chinese steering committee dates back to June 2016. “To suggest that we've suddenly discovered that the Chinese might not want to cooperate with us inside their research teams is farcical,” a former advisor to Presidemt François Hollande says today. “The real China specialists have always known it would be like that.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter.