In an interview published on Wednesday, Sir Richard Dearlove, the former head of British foreign intelligence agency MI6, said he had seen an “important” recent scientific report which suggested the Covid-19 virus was produced by Chinese scientists, and that the pandemic that has spread across the globe was the result of an accidental leakage of the coronavirus strain from a research laboratory in the city of Wuhan, in China's Wubei province.

Dearlove’s comments to British daily The Telegraph, in which he also raised the possibility of China facing a demand for reparations on behalf of the victims (including more than 368,000 dead worldwide in a June 4th count by Johns Hopkins University) and for economic damage caused by the virus, were swiftly dismissed by Yuan Zhiming, the director of the high-security lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. "We have never participated in designing and making a new virus and will not do that ever," he was quoted as saying by state-run news agency Xinhua.

The allegations that the virus pandemic which began in the city of Wuhan was the result of a leakage from the lab have previously been dismissed by a number of scientific reports which have concluded that it began from contact with infected host animals, and most likely pangolins, sold at so-called “wet” markets, although the exact origins have not yet been established.

But the comments by the former MI6 boss have served to highlight suspicions over the nature of the operations conducted at the Wuhan lab, which is a French-designed facility inaugurated in 2017 at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in the presence of then French prime minister Bernard Cazeneuve. As Mediapart has previously detailed in the first of this two-part investigation into its history, since the lab's inauguration France has been kept at a distance from its activities despite planned cooperation with French researchers.

The lab was the result of agreements signed in 2004 between France and China for cooperation in research into emerging diseases, inked by then French president Jacques Chirac and his Chinese counterpart Hu Jintao.

The first of the two agreements, signed in January 2004, was for France to supply China with four mobile biosafety level-3 laboratories – more often abbreviated as BSL-3, or P3 – for biological research. But already, 16 years ago, the deal got off to a stuttering start.

The French P3 labs, designed to operate in a tightly controlled environment adapted for the study of a wide range of virus types, including coronavirus, were blocked for four months in late 2004 at the northern French port of Le Havre. This was officially to allow for technical verifications of the equipment, but behind the move was the DST domestic intelligence agency, the General Secretariat for National Defence (SGDN) and the customs administration, in a clear indication of their reticence over the cooperation deal, which was to lead to the transfer to China of the P4 laboratory, which meets the highest biosafety level, and which is now the centre of controversy.

At the time, about only a dozen P4 – or BSL-4 – labs, equipped to handle Class 4 pathogens, which include deadly viruses such as Ebola, existed in the world, and it was common knowledge that the Chinese military were closely involved with the activities of the country’s civilian biotechnology research institutions.

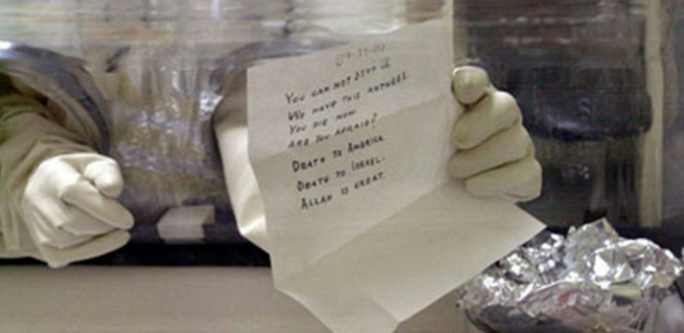

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Bernard Connes, founder of French laboratory equipment supplier Labover, which manufactured the initial P3 labs destined for China, recalled that the contract for the supply of the P3s was signed jointly “by the Chinese ministries of health and [that] of defence”. The fears that the labs were intended for both civilian and military research purposes appeared founded.

Alongside these concerns of proliferation, as the term applies to biological arms as well as nuclear and chemical weapons, there was a European-wide embargo on the sale to China of offensive weapons, a move introduced in 1989 in response to the repression of the so-called Beijing Spring pro-democracy movements and notably the Tiananmen Square massacre. The then French prime minister, Jean-Pierre Raffarin, had declared his government “in favour of lifting this embargo, at the highest level, with no ambiguity”, adding that the embargo was “anachronistic” and “unjustly discriminating”.

The scientific cooperation with China led necessarily to the involvement of the Chinese military. Following the 2002-2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) virus epidemic, the Chinese army created a unit dedicated to researching emerging virus diseases, with a specific headquarters and a network of local agencies in every military region.

Illustrating this was the management of the coronavirus crisis in Wuhan. On January 30th this year, as the Covid-19 pandemic spread across the world from its epicentre in the Chinese city, Chen Wei, an epidemiologist with the rank of major general in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), was appointed to take over the operations to contain the epidemic in Wuhan, leading a team composed of members of China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences, the academy’s Institute of Biotechnology and researchers from Chinese vaccine-making firm CanSino Biologics. Their official task was to develop an experimental vaccine. Chen Wei was overnight the subject of glowing Chinese official media reports, which even described her as a “goddess of war”, whereas her military grade and role as one of China’s leading experts in biochemical weapons had never previously been communicated in public.

Jean-Claude Mallet, Francis Delon and Louis Gautier, the successive heads of France’s General Secretariat for National Defence (SGDN) – an inter-ministerial body now renamed General Secretariat for National Security and Defence (SGDSN), which directly advises the prime minister’s office – have all expressed serious doubts about the French bio-lab technology cooperation deal with China. They were notably concerned about the legal issues facing France given it had signed up to international agreements limiting the exportation of such sensitive know-how and equipment, and which the US state department also repeatedly raised in its attempts to block the 2004 deal.

The SGDN carried out a major study of the legal issues. For apart from the construction plans for creating the labs, exports of equipment to be used in them (such as autoclaves and confinement blocks) are also subject to strict conditions as set out in so-called “multilateral export control regimes” such as the Wassenar Arrangement, the Australia Group and a December 1994 European Union (EU) agreement on the control of exports that are potentially of dual use.

France’s inter-ministerial commission with responsibility for dual-use exports, the CIBDU, intervened to block the export of some of the equipment ordered by China in the period 2015-2016. This concerned the request for a batch of positive pressure suits designed for staff working in the P4 lab in Wuhan, and which followed an earlier delivery of similar suits in 2010. The CIBDU refused to authorize the delivery of the suits, on the basis that quantity requested was greater than required for the facility. “That order clearly raised fears over the use of the suits at undeclared sites,” explained a senior French civil servant, speaking on condition his name was withheld.

In 2005, the French parties involved in providing China with the P4 lab handed over the construction plans, via the China Academy of Building Research, to local firms including the IPPR Design Institute and the Wafangdian Engineering Company.

Some expert China watchers, as relayed on the Taiwanese website Bearpost, an outlet for confidential reports from within China, have claimed – although without providing the proof – that one, or possibly two, P4 labs have been built in China based on the model exported by France.

Informed sources have told Mediapart that France’s foreign intelligence agency, the DGSE, which like those elsewhere is attempting to determine the exact origins of the epidemic in Wuhan, has since January this year made investigating the possible existence of the copied labs one of its priorities. If the P4 lab in Wuhan was duplicated, it would be a clear breach of the terms of the cooperation deal between France and China.

Chinese general sees biology as 'a new domain of warfare'

While the international community has largely succeeded in protecting itself from the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the difficulties in placing controls on the development of biological weapons leaves it largely exposed to their dangers, whether they be deliberate or accidental.

The revelations in the early 1990s of the Soviet Union's biological warfare programme Biopreparat confirmed the reality of the threat. Disguised as a civilian operation under the auspices of the Soviet Ministry of the Medical and Microbiological Industry, Biopreparat, which at its height employed more than 70,000 people, was a vast network of laboratories with activities ranging from biological research to the industrial production of weapons tested in the Aral Sea, a vast lake now largely dried up. It was the defection of Soviet biologist Vladimir Pasechnik, a leading scientist in the programme who ran the Leningrad-based Institute of Ultra Pure Biochemical Preparations, who sought asylum in 1989 at the British embassy in Paris, that brought an end to the secrecy of the bioweapons network.

In 1999, the independent Center for Nonproliferation Studies (now renamed as the John Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies), based at Monterey in California and one of the largest NGOs dedicated to research on mass-destruction weapons, identified 19 countries as having been possibly involved in developing biological weapons during the previous decade. These included China, Egypt, Iran, India, Iraq, Israel, Libya, North Korea, Russia, Taiwan and the US. As of 1995, following the First Gulf War of 1990-91, the discovery of the size of the Iraqi biological weapons programme – which was completely dismantled – revealed the gravity of the phenomenon.

At that time, China, despite signing up to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC) in 1984, was suspected of having continued to maintain the offensive biological weapons programme it created on the Soviet model during the 1950-53 Korean War, and which notably included the use of anthrax, glanders, botulinum toxin, typhus and cholera.

In 1999, Kanatjan Alibekov, a former senior director of the Soviet Union’s Biopreparat programme, who adopted the name Ken Alibek after gaining asylum in the US, published a book in which he claimed that, in the late 1980s, Soviet satellite pictures had identified what was believed to be a bioweapons plant in north-east China, when he also speculated that an outbreak of haemorrhagic fever in the same region may have come from the site.

In an August 2019 report entitled ‘Adherence to and compliance with arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament agreements and commitments’, the US state department noted: “China continues to develop its biotechnology infrastructure and pursue scientific cooperation with countries of concern. Available information on studies from researchers at Chinese military medical institutions often identify biological activities of a possibly anomalous nature since presentations discuss identifying, characterizing and testing numerous toxins with potential dual-use applications.”

The latter concern about ten sites that are connected to the Chinese state-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), a body with multiple responsibilities, including R&D for defence equipment, and which collaborates on bio-medical research projects with the science and technology ministry and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The China National Biotech Group, managed by the SASAC, instigates and supervises the activities of a section of the vaccine-producing industry. These interconnected interests are not unique to China; in France, the defence procurement administration, the DGA, funds civil research projects, including some undertaken by the Pasteur Institute, without there being any suggestion that they contravene international law.

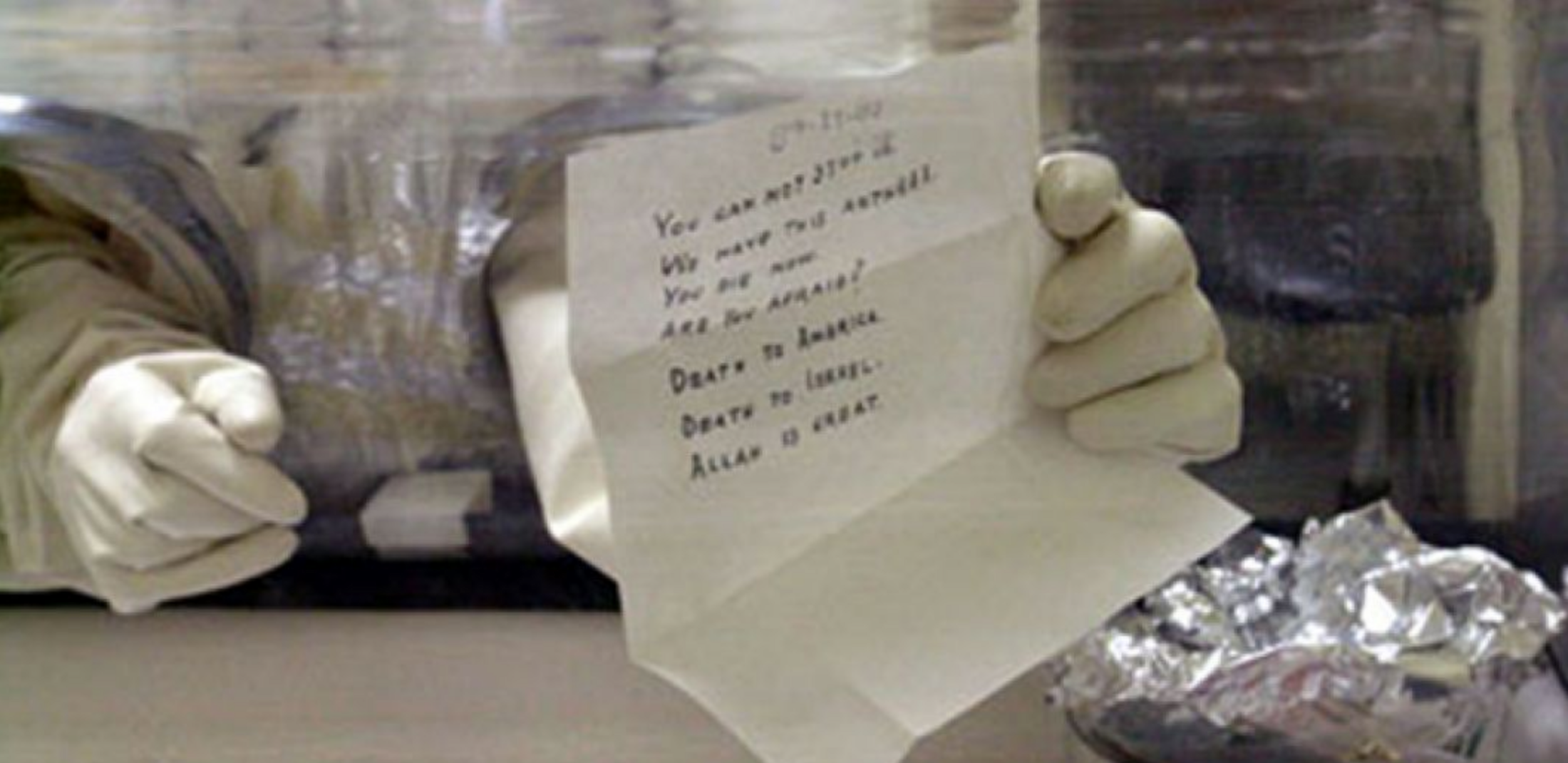

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Biotechnology sites linked to the SASAC are found at Lanzhou, Changchun and Wuhan – where, along with the French-built P4 lab, there are five P3 labs, most of them designed by China. Writing in the April-June 2015 edition of the Journal of Defence Studies, published by the Indian Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Israeli researcher and former military intelligence officer Dany Shoham cited Taiwanese sources as identifying four sites which are involved in research activities that may have dual civilian and military purposes. These are located at the southern city of Kunming, the south-west city of Chungking, the north-east city of Changchun and also Wuhan, in central China.

In New Highland of War, a 2017 book published by China’s National Defense University Press, retired general and former president of the PLA’s National Defence University, Zhang Shibo, described biology as one of seven “new domains of warfare”. The US magazine Defense One translated an extract from the book in which Zhang argued that “modern biotechnology development” was “gradually showing strong signs of an offensive capability”, including the possibility of “specific ethnic genetic attacks”, meaning the targeting of genetic particularities of an enemy. That view is also shared by Western military strategists, and once again illustrates how medical research crosses into weapons research.

China is one of the few countries that have been the target of biological weapons. Between 1933 and 1945, Japan made massive use of them against the Chinese population, notably in Manchuria.

After signing up to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and On Their Destruction, (BWC), in 1984, China has been active in publicly defending it. In the text of the French-Chinese cooperation agreement for research into emerging diseases, which was the framework for France’s supply of the P4 lab in Wuhan, there is a specific reference to the requirement to respect the BWC. China has also highlighted that it is the US which has blocked the adoption by the BWC of a programme of verification that signatories abide by the terms of the convention. But the reality of China’s stand on biosecurity has at times appeared little more than posturing.

The 'Variant U' virus taken from dead lab doctor

The French-designed P4 lab in Wuhan is a replica of that built in the south-east city of Lyon by the Mérieux Foundation, named after the Mérieux family behind the holding company Institut Mérieux, which in turn owns the French pharma giant bioMérieux. The man at the head of the Lyon-based family business today is the billionaire and former local conservative politician Alain Mérieux.

But already, during the late 1990s, before the epidemics of SARS and avian flu which the Chinese authorities had difficulty containing due to the country’s lack of appropriate technical resources, Mérieux had wanted to supply China with equipment duplicated from his pharma plants in Lyon.

Mérieux had the backing of advisors to then French president Jacques Chirac but met with opposition from the then socialist defence minister Alain Richard and also the national defence general secretariat, the SGDN. They were notably concerned about the crossed boundaries between civilian and military research, and China’s record in the proliferation of weapons, notably its supplies of equipment to North Korea.

Complicating matters further was that the conservative Chirac was sharing power at the time with a socialist government, led by prime minister Lionel Jospin, who was wary of the president’s active, high-placed networks of influence.

Within the socialist government, which was in power until general elections in 2002, the defence ministry maintained its opposition to the project, with the support of the SGDN. The ministry’s “delegation for strategic affairs” (now renamed as the directorate for international relations and strategic affairs, or DGRIS) was in charge of closely monitoring the affair, in conjunction with the defence procurement agency, the DGA.

Also involved was the foreign intelligence service, the DGSE, which was tasked with tracing the sources of components used in weapons of mass destruction, from nuclear matter to chemical and biological ingredients. This was in tandem with France’s military intelligence agency, the DRM, which focused on the equipment used for launching the weapons.

“In our internal discussions, the issue of the treatment of health risks, [which was] very important in China where some regions remain proper medical deserts, prevailed over the military sector,” said a former foreign intelligence official with close knowledge of the events, speaking on condition his name was withheld. “In the end, that was what founded our position over the P4 […] The more so given that the Chinese case had nothing in common with the Soviet Biopreparat programme. Then also, there is always a gap between the intention of developing a biological weapon of mass destruction, the capacity for proliferation, and that of developing an operational framework. What’s more, this kind of clandestine activity sooner or later ends up being revealed, which encourages a country like China to be prudent.”

But what must also be taken into account is the difficulty for Western intelligence agencies to operate in China, where opportunities on the ground to gain key sources for information are rare. By excluding any outside cooperation with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the Chinese authorities made sure that such agencies were unable to use foreign staff, and notably French scientists, on detachment there to garner details about research programmes and the use of the labs.

However, the DGSE’s counter-proliferation intelligence gathering proved successful elsewhere, such as in the case of Iraq. The French agency was able to determine that the US and British claims at the end of 2002 that the Saddam Hussein regime had built up an arsenal of nuclear, chemical and biological weaponry was untrue, and that contributed to Jacques Chirac’s refusal to join the 2003 invasion of the country.

Interviewed by Mediapart, a former member of France’s national intelligence council (Conseil national du renseignement, or CNR), a coordinating body for all of the country’s spy agencies, said the reservations by the DGSE and others over the supply of the P4 lab to China – part of the scientific cooperation agreement which Chirac had finally signed in 2004 – were above all motivated by the necessity “to guard against the risk of a reproduction of the technology of the French lab at a time when Chinese companies were more and more active on a scale of entire continents, like in Africa”. In short, the caution over the export of the lab was, according to him, as much a question of protecting French economic interests as an issue of security.

The danger of accidents in laboratories researching potentially deadly pathogenic or infectious agents constitute a threat as great as that of a deliberate biological attack. On the basis of recorded incidents at biological research institutes, the risk of an accidental or deliberate hazard from biotech laboratories is, relative to their numbers, estimated by the World Health Organization to be 0.03% per laboratory per year.

What might be called “near-miss” incidents include an explosion and subsequent fire which occurred in September 2019 at a Russian virology and biotechnology research plant called Vector, situated near the city of Novosibirsk in south-west Siberia. Vector, also known as the Vector Institute, used to be part of the Soviet Biopreparat network. According to Russia’s federal agency for consumer rights and human wellbeing, Rospotrebnadzor, the blast was caused by an exploding gas cylinder, and officially no dangerous substances were leaked.

The same plant was the scene of an accident in 1988, as recounted by former senior Biopreparat director Ken Alibek. He has detailed how in April that year a researcher at Vector, Doctor Nikolai Ustinov, accidentally pricked himself with a needle he was using, inside a P4-category lab, to infect guinea pigs with the Marburg virus, which is closely related to the Ebola virus. His experiments were part of Soviet research to develop biological weapons. According to Alibek, the strain of the virus that killed Ustinov within weeks was removed from samples taken from his corpse and further research was carried out for its use as a weapon. The particularly infectious strain, Alibek said, was named “Variant U” after the doctor’s name.

In April 1979, at another Soviet research site near the city of Sverdlovsk, close to the Ural Mountains, anthrax spores were accidentally released. The precise number of deaths caused by the leak is uncertain, but estimated to number several hundred. It was that accident that provided the first clear evidence of the secret Soviet programme to develop biological weapons.

Deliberate poisoning by anthrax occurred in the US in September 2001, shortly after the World Trade Center terrorist attacks, when a series of letters containing anthrax spores were posted to news media and senators Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy. Five people were killed and several others infected. After several years of investigation, Bruce Ivins, a scientist at the US army’s Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases based at Fort Detrick in Maryland was identified by the FBI as being the prime suspect. Ivins, 62, was found dead in July 2008 in an apparent suicide before charges were brought against him.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The same Fort Detrick research centre, which apart from anthrax handles dozens of other toxins and infectious agents, including the Ebola virus and the plague bacterium, was temporarily closed down in July last year after it was discovered that its system for decontaminating wastewater from the labs was insufficient.

Also in the US, in 2014, a laboratory in Atlanta, part of the network of US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was closed down after a series of safety failings, including the sending of potentially infectious samples of anthrax bacteria to laboratories unequipped to handle them.

In September that same year, at a GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) polio vaccine research plant in Rixensart in Belgium, located about 20 kilometres from the capital Brussels, 45 litres of liquid contaminated with poliovirus were released from the site into the local sewage treatment plant and subsequently into the Lasne River following an error by one of its staff. A GSK spokesman said that the incident involved "an accidental discharge of cleaning solution that had been used to sanitize equipment used in the manufacture of polio vaccine".

Meanwhile, in France, the Pasteur Institute, also in 2014, revealed that 2,349 vials containing fragments of the SARS virus had disappeared, unaccounted for, from one of its P3 labs. It said the lost vials represented no danger to the public because they could not have left the lab without being sterilised.

During the 1990s in France, the national institute of research and safety (l’Institut national de recherche et de sécurité), an association composed of trades unions’ and employers’ representatives which reports on work safety issues to the social security administration, set about identifying how to reduce accidental dangers to staff working in biotech environments where they manipulate infectious agents. As a result of their consultations, a series of safety measures were introduced which led to a significant improvement; in 1996, according to a study of workplace doctors, there were five recorded cases of staff contaminated by infectious diseases as a result of their professional activities, but with the implementation of the new safety regulations shortly after, no further cases of contamination in France have since been recorded.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------