An estimated eight million people in France live in cold habitations which they cannot afford to heat, causing them to suffer significantly more illnesses than the wider population and which further exacerbate the suffering caused by economic poverty alone.

That is the conclusion of the first-ever methodical and large-scale study of the problem in France, presented in October in a report by a leading French charitable association for the poor, the Abbé Pierre Foundation. Its alarming findings closely mirror those of previous studies of the issue in other countries.

The Abbé Pierre Foundation’s research used a definition of cold living conditions as those where the temperature was inferior to 16° Celsius. Many of these were found in insalubrious lodgings which had aggravating problems, like damp, poor ventilation and mould.

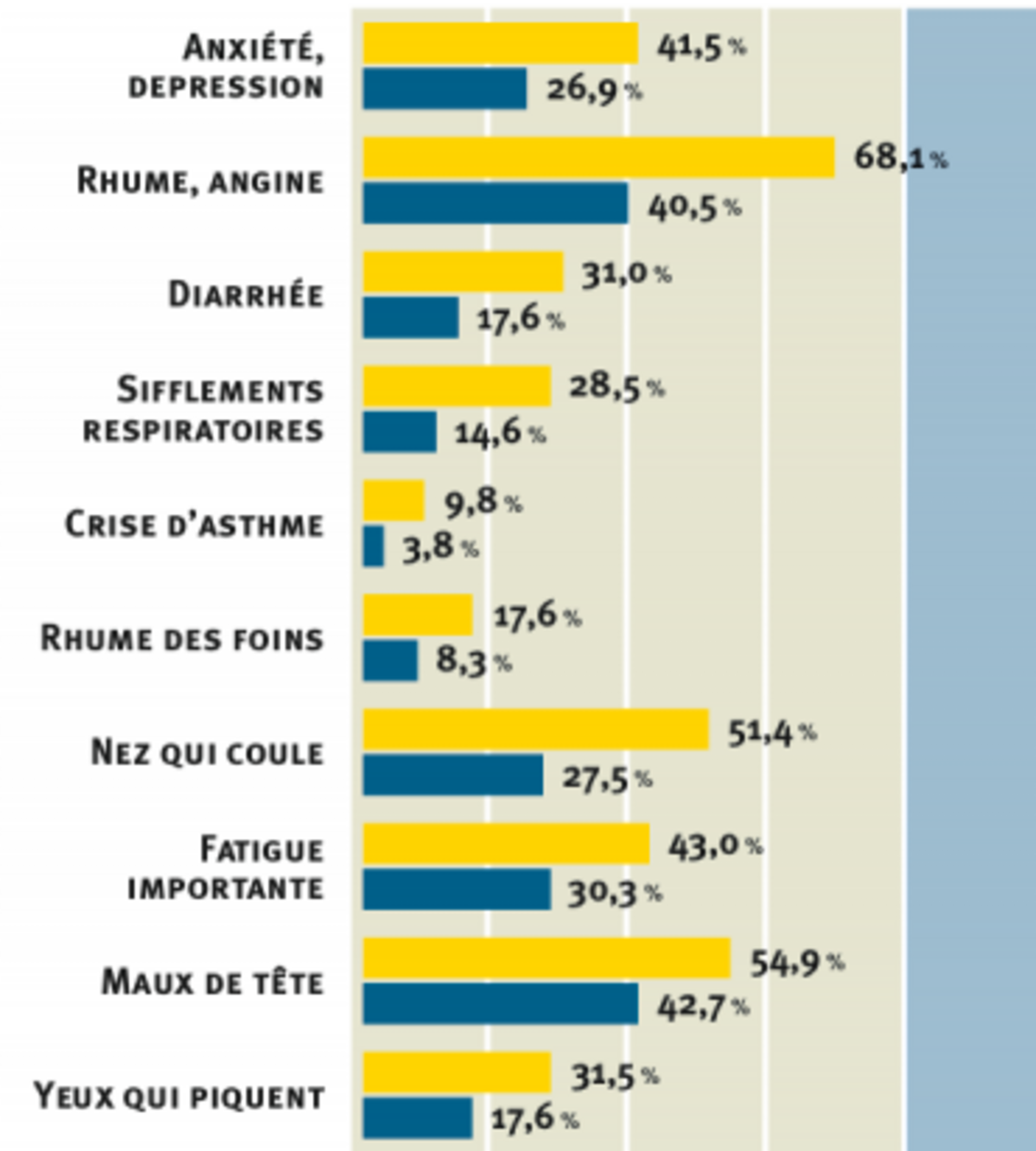

The study compared health complaints among those living in none- or poorly-heated homes and among those whose homes were comfortably heated. The higher rate of illnesses (see chart below) ranged from those of depression and anxiety, chest and throat infections to allergies, eye irritations, diarrhea and headaches.

The comparisons showed major differences: complaints of colds and tonsillitis were common to 68.1% of those in cold living conditions, against 40.5% for those in comfortably heated homes. Complaints of anxiety and depression were common to 41.5% of those in cold homes, compared to 26.9% among comfortably heated homes. Other comparisons showed significantly more cases of asthma (respectively, 9.8% against 3.8%), headaches (respectively, 54.9% against 42.7%), diarrhea (respectively, 31% against 17.6%) and major fatigue (respectively, 43% against 30.3%).

“The cold affects blood circulation, which can lead to heart attacks, strokes, and also acts against the defence system, which can have a role in allergies,” commented Bernard Ledésert, the study’s technical director.

The survey was carried out in two distinct regions with contrasting weather conditions, in partnership with two local charitable associations concerned with living conditions among the poor; the PACT, in the northern Douaisis region close to Lille, and the CREAI-ORS, in the southern Languédoc-Roussillon region.

The associations’ aid workers questioned families whose situations they were already familiar with, using a standard questionnaire, completed in the Languédoc in 2012 and earlier this year in the Douaisis. “This survey permitted an objective presentation of what professionals have for several years witnessed on the ground intuitively,” said Patrick Cornille, chairman of the PACT.

Almost 300,000 households in the northern Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, of which a large part is made up of the Douaisis, are estimated to be affected by energy poverty. The survey in the Douaisis involved 195 households (representing 280 people above the age of 16) of which 146 were affected by energy poverty. More than four out of five people affected by energy poverty lived below the economic poverty line.

A first step of recognition

The conclusions of the study now begs wider national studies like those carried out in Britain, the US, New Zealand and by the World Health Organisation. “The links between health and bad housing are badly strung together,” said Véronique Stella, the project director for PACT, underlining that until now there had been little attempt in France to approach the issue of improving poor housing conditions through the consideration of the illnesses they cause.

A study in Britain in 2011, commissioned by Friends of the Earth and led by Professor Sir Michael Marmot of the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at University College London, resumed its findings on the direct repercussions on health of "cold housing and fuel poverty" as follows: “Countries which have more energy-efficient housing have lower Excess Winter Deaths (EWDs). There is a relationship between EWDs, low thermal efficiency of housing and low indoor temperature. EWDs are almost three times higher in the coldest quarter of housing than in the warmest quarter (21.5% of all EWDs are attributable to the coldest quarter of housing, because of it being colder than other housing).”

“Around 40% of EWDs are attributable to cardiovascular diseases,” it continued. “Around 33% of EWDs are attributable to respiratory diseases. There is a strong relationship between cold temperatures and cardio-vascular and respiratorydiseases. Children living in cold homes are more than twice as likely to suffer from a variety of respiratory problems than children living in warm homes. Mental health is negatively affected by fuel poverty and cold housing for any age group. More than 1 in 4 adolescents living in cold housing are at risk of multiple mental health problems compared to 1 in 20 adolescents who have always lived in warm housing. Cold housing increases the level of minor illnesses such as colds and flu and exacerbates existing conditions such as arthritis and rheumatism.”

The Abbé Pierre Foundation first began exploring the problems following reports during the last decade by social services and the energy suppliers of increasing numbers of households that were unable to pay energy bills. Since the so-called ‘Grenelle de l’environnement’, a government-led consultation process in 2007 aimed at limiting damage to the environment caused by industrial, economic and social practices, the Foundation has worked closely with NGOs concerned with ecological issues, including the Fondation Nicolas Hulot, France nature environnement and the Réseau Action Climat.

In 2012, the Foundation was the coordinating body for a joint appeal with 34 organisations concerned with social deprivation and environmental matters, from the French Red Cross to Greenpeace, entitled ‘For an end to energy poverty’ (En finir avec la précarité énergétique).

It called for the introduction of an ‘energy shield’ that would allow every home to receive essential utility services, estimating that some four million homes in France were in a condition of dire thermal inefficiency. Just 7% of these households would benefit from recent government programmes to encourage property owners to improve the energy efficiency of their premises, it argued, stressing the urgency for both social and environmental interests in creating a vigorous national policy to address the problem.

A law introduced in March this year, broadly aimed at encouraging more efficient use of energy, included measures to extend, to 4.2 million, the number of households entitled to lower, publicly-subsidized energy bills, estimated to include a total of eight million people. But there have been delays in putting the measures into effect, as highlighted by the official ombudsman for energy issues. Meanwhile, a national plan launched earlier this year to encourage the renovation of thermal insulation of properties, which includes lower VAT rates on work commissioned, has come under criticism for including obsolete norms and for benefitting above all middle-income households rather than the poor.

Following up on the study, which represents one of the first steps in France towards a public recognition of the importance of the issue, a conference is to be held in December in Paris which will bring together specialized researchers from the academic world and activists from associations involved with poverty issues. Representatives of the ministries of health and ecology have not yet confirmed their participation, raising serious doubts that the issue of energy poverty will be absent from the priorities in a bill of law on energy transition due before parliament in 2014.

The Abbé Pierre study further illustrates that the process of the transition of energy supply and usage cannot be limited to questions of kilowatt consumption, attempts to kick-start the construction industry and easier access to credit from banks. Beginning in the 1970s, environmental groups in the US and Britain have placed the issue of social inequality on the agenda of environmental policy making, highlighting the particular and unequal vulnerability of the poor to situations of pollution and noxious environments.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse