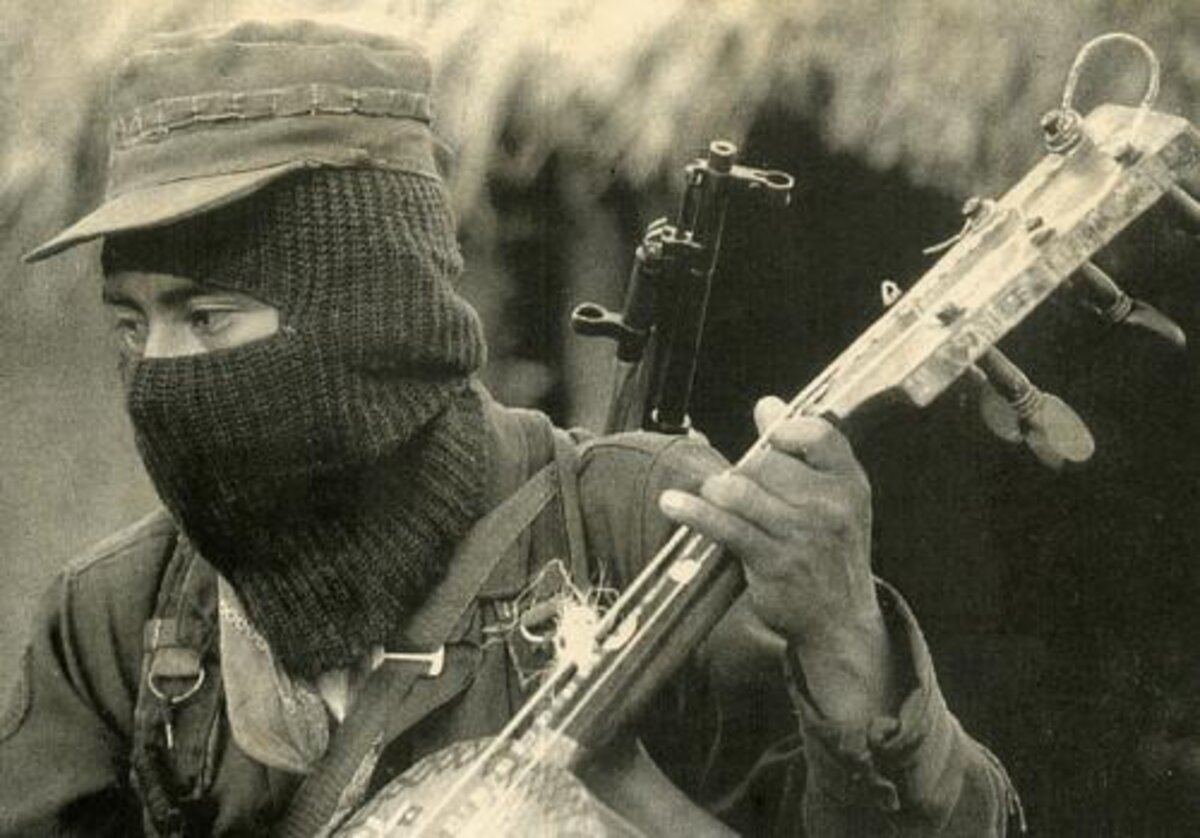

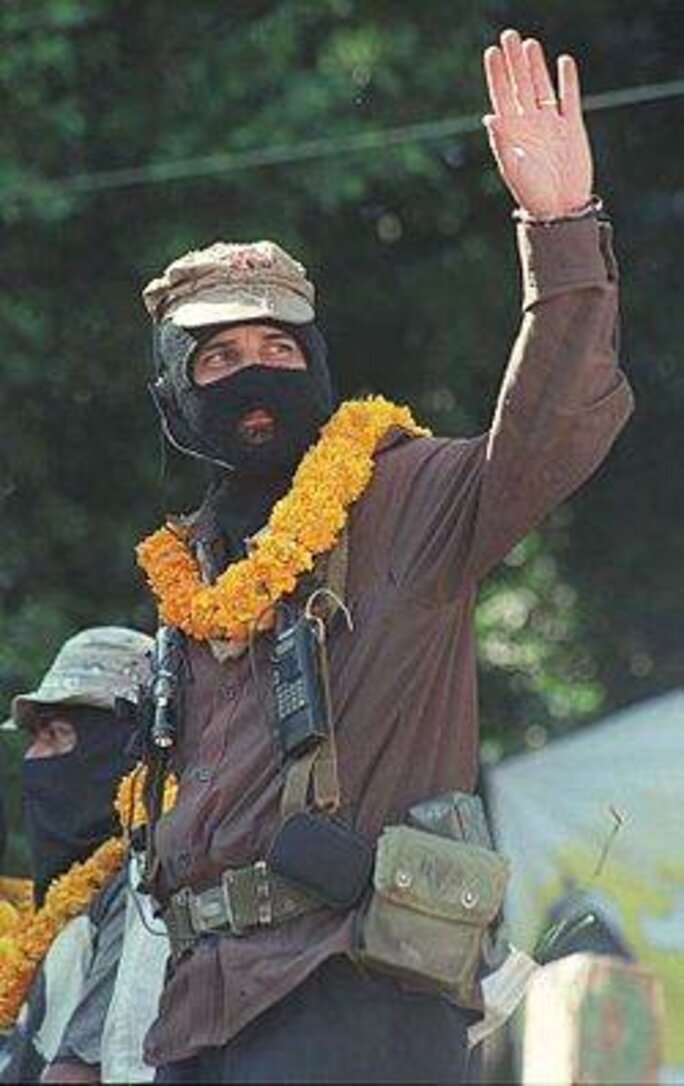

Exactly 20 years ago the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, bringing Mexico into a free-trade bloc with the United States and Canada. In response the Zapatista Army of National Liberation immediately began an uprising in the Chiapas region of southern Mexico against the treaty's abandoning of rules that protected Amerindian land. The organisation, usually just known as the Zapatistas, began life as a guerilla movement before transforming itself into a commune-based political and military group which symbolised resistance to global neoliberalism. This resistance spread and eventually fed into the Alter-Globalisation Movement and the Global Justice Movement, which grew out of protests at the 1999 World Trade Organisation (WTO) summit.

However, across the Atlantic, at the same time as the Zapatista uprising, a rather different theory was taking hold. In 1995 the eminent French historian and former communist François Furet published his seminal work, Le Passé d’une illusion, Essai sur l'idée communiste au XXe siècle ('The History of an Illusion, an essay on the communist ideal in the 20th century', Éditions Robert Laffont). His well-known conclusion became a stick with which to beat the next generation of militants: “The idea of an alternative society has become almost impossible to imagine in today's world, and in fact no one is making progress on this subject, not even on an outline of a novel concept. That leaves us condemned to survive in the world in which we are currently living.”

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis these two opposing camps - those who still see the potential to create a different society on the one hand and devotees of the “end of history” mantra on the other – have come under fresh scrutiny. This re-evaluation has in turn given new impetus to the idea of a post-capitalist world, and not just among researchers who define themselves as Marxists or post-Marxists.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Amongst this new wave of thinkers Jérôme Baschet has a distinctive profile. Though a specialist in medieval history at one of France’s top social science institutes, the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), he has developed a particular interest in the Zapatista movement. The historian is the author of several articles on the Zapatistas and has taught at the Chiapas Autonomous University in Mexico since 1997.

Baschet has also just published an ambitiously-entitled book, Adieux au capitalisme. Autonomie, société du bien vivre et multiplicité des mondes ('Farewell to Capitalism – Autonomy, the Society of Well-Being and a Diversity of Worlds'), which takes the Zapatista movement as a starting point to “increase thinking about alternatives to capitalism and the potential that would be opened up by going beyond it”.

The book has been chosen by Éditions La Découverte to inaugurate a new series of works under the title L’Horizon des possibles ('The Horizon of Possibilities'). The publishers say this collection is a response to the disarray of anti-neoliberals, stating that “neither speculative pamphlets, even brilliant ones, nor explanations of reality, even subtle ones, are sufficient nowadays for social criticism. This requires the setting out of theories and observations, of studies and their subjects, of new ideas and current practices.”

Baschet's book examines in detail the way the Zapatistas set up autonomous communities in Chiapas, which he calls “one of the most remarkable real utopias” to be tried in the world and “a source of inspiration for conceiving a non-state political form based on de-specialisation and a collective re-appropriation of the ability to take part in decision-making”. In this, Baschet echoes a term coined by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano who writes about the “democraship” of the market, a word evoking the twin rule of political democracy and market dictatorship which has failed to prevent rising inequality or unacceptable living conditions.

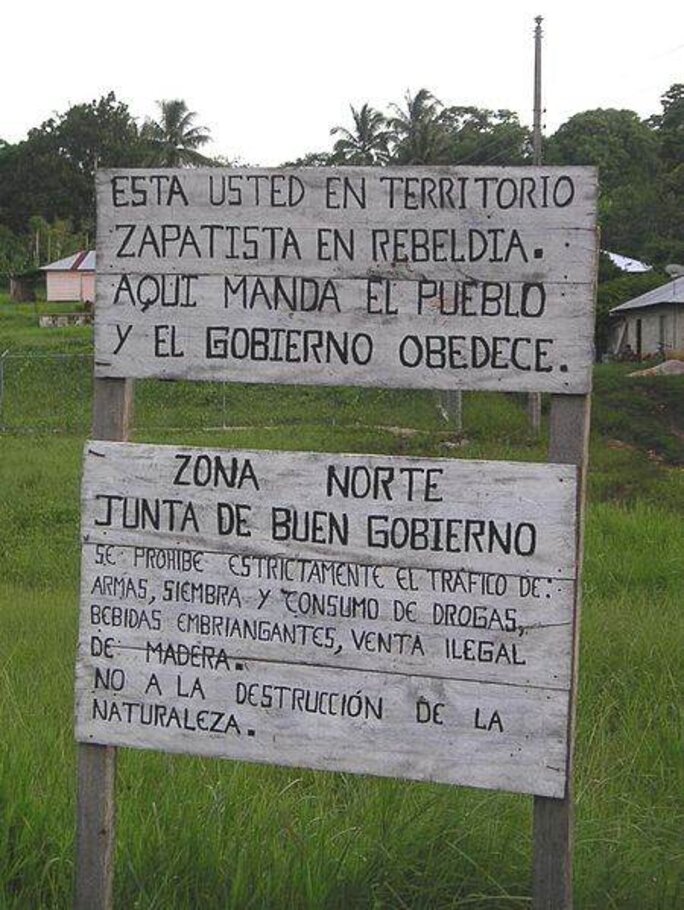

In the wake of the 1996 San Andrés Accords on indigenous rights and culture, which the Mexican government later reneged on, the Zapatistas set up autonomous communes on a land area the size of Belgium that was home to several tens of thousands of Maya and Zoque Amerindians as well as non-indigenous families.

Baschet describes how each community elects representatives to its Council of Good Government for a period of two or three years under mandates that can be revoked at any moment and which are considered as services for which no remuneration is due. Each commune also sends two or three representatives to the Council of Good Government in the neighbouring zone on the same basis.

A 16-hour working week...

The Zapatistas' aim has been to install an institutional framework to “translate into practice a non-specialist conception of governmental tasks”. The communities have set up their own registers of births, deaths and marriages and specific education systems. It is an attempt to put into practice the Zapatista ideology of 'mandar obedecienda' ('leading by obeying'), which does not exclude maintaining some degree of vertical hierarchy for implementing decisions or for dealing with emergencies. But it does seek to avoid a concentration of power and aims to alter the relationship between the government and the people to make it a genuine two-way process.

Baschet recognises the slowness of collective debate and consultation that such a system entails. This can appear disconcerting, he notes, “particularly as it is often necessary to pass [an issue] on to another team that will re-examine it from scratch”. In this he echoes the title of a work by Francesca Polletta, professor at the University of California Irvine, Freedom is an Endless Meeting (see right), a study of various ultra-participative forms of democracy that have been tried during the 20th century in the United States. But, he says, this slowness could become an advantage if people simply adopt a different mindset, albeit one unfamiliar to those whose world-view is shaped by modern Western life.

Baschet uses the Zapatista example to outline “a post-market society” and a “post-capitalist world involving self-government at all levels, radical limits on the demands of production and a de-specialistion of social functions” - even in healthcare, although he concedes that some areas of health still require years of training, solid experience and specially-equipped places to practice them.

He also develops an idea he calls a “revolution of time”, in which he postulates that if work were shared equally between all of a community's members, they could produce most of their food and manufactured goods and provide essential services by working fewer than 12 to 16 hours per week. He backs up this assertion with detailed calculations in an appendix, and even wonders if his sums may still be too conservative.

It would be easy to criticise this book for its political partisanship and sometimes rarefied tone – parts of it seem to be written more as a manifesto than an analysis – or to contest some assertions, such as that in Japan “a quarter of high school girls use prostitution to be able to buy make-up and the latest fashions”. The potential outcomes Baschet envisages are also rather a mixed bag – for example he advocates eliminating all military and police roles, banks and insurance companies, advertising and marketing, and bureaucracy. And it is a shame that his descriptions of the ravages of capitalism are far more numerous than those of convincing alternatives, although he asserts: “We have begun to create the world we dream of.”

Even so, the book has a refreshing realism. Baschet disabuses those who harbour illusions that capitalism is in its death-throes. Yes, he lists at length the many predatory aspects of capitalism, from destruction of the environment and the biosphere in the name of profit to the pressures on social systems created by its reduction of people to isolated individuals. But he also refers to “capitalism's flexibility”, saying that nothing that has taken place since 2008 “suggests that we have entered the sequence of a final crisis of capitalism”.

It is therefore pointless, Baschet contends, to expect that simply highlighting the dysfunctional aspects of neoliberalism will automatically lead to the change of civilisation he advocates. “The traditional strategy of revolution, centred on seizing state power, has fizzled out,” he argues, and recent resistance movements do not seem to present any real threat to the bastions of financial power either.

Too many contradictory scenarios are presented for the end of capitalism, Baschet continues. “Some focus on the ravages of a fetishisation that locks people's minds and bodies into a system that is collapsing, while others envisage the exit from market supremacy as a kind of exodus produced by an act of will, or imagine a post-capitalist society emerging from the technological and productivity transformations promised by capitalism itself.

“Often the transformation of the system is seen in a molecular way, as a multiplication of current micro-initiatives, rather than in the abbreviated form of a future Great Event,” he says. But, argues the historian, in trying to differentiate themselves from the old notion of Revolution with a capital 'R', the proponents of these scenarios run the risk of being trapped inside the mirror image of what they are fighting.

Baschet does not claim to have written a manual for exiting capitalism, but he does advocate three main courses of action to head in that direction: increasing the number of “liberated spaces”, such as in Chiapas; collective resistance and construction, and being able to rely on other forces besides “our own”.

The myth of social mobility

But Baschet's most singular and interesting contribution is probably in his analysis of the creative tension between the South and the North, between culture and nature or between human and non-human. His critique of capitalism is informed by his knowledge of the way Amerindians in Chiapas live, without making indigenism a banner of authenticity or a blueprint of resistance to neo-liberalism.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Given there is no single way to exit capitalism, Baschet says, what is needed is a dialogue between anti-capitalists in the North and their counterparts in the South. Very often, he says, criticism of capitalism in the North is too wrapped up in Western ways of thinking, stuck “in realities specific to a universe that is perhaps still a nerve centre but which is increasingly limited compared with the size of the world population”. In the South, meanwhile, criticism tends to drift from anti-capitalist anti-colonialism to condemning an overblown idea of the West. There is a need for an inter-cultural dialogue “that will be based neither on the relics of Western-centred thinking nor on the denial of the West”.

Baschet goes on to argue that in order to build a post-capitalist civilisation that will exist in a diverse world, we first need to abandon the myth of progress that reduces the struggles and revolts of many peoples around the world to a backward-looking defence of traditions. As counter-examples to this view he holds up the Yellow Turban Rebellion, a peasant insurrection in China in 184 AD, and the Quilombo dos Palmares communities founded by escaped slaves in Brazil that existed for most of the 17th century.

Baschet does not give credence either to the idea that non-Western societies have an essentially “egalitarian” quality or that the West has the monopoly on a “democratic vocation and liberating mission”. Instead he places emphasis on the attachment to well being that “is anchored in the values and traditional practices of Amerindian peoples”. However, at the same time he refuses to reduce this to a cult of Amerindian history or to a fixed idea of the nature of indigenous peoples.

In adopting this approach, Jérôme Baschet promotes the idea of what he calls “inter-cultural pluniversalism”, a new expression meaning that the concept of a common world – a different take on the traditional idea of the “common good” linked to the power of the state – starts from the notion of “self-governing local communities”. This common world is also based on awareness of “belonging to the human community on Earth, which is itself indissociable from the bio-community of humans and non-humans”.

Baschet argues that this approach opens up new opportunities that get away from the problem of growing social inequality that is either hidden “under the cloak of formal equality” or underestimated “thanks to the (somewhat crumbling) myth of social mobility”. These opportunities are arising because there are “other issues at stake, which are becoming more and more pressing, and which concern a growing section of humanity” and not only those who suffer injustice.

For the author, the very uncertainty over “the conditions for survival of the human species” due to the damage already wreaked by capitalism, including to the environment, is fast becoming “one of the most powerful impulses behind anti-capitalism criticism”. The anti-capitalism movement, Baschet says, should be able to “harness humanity's survival instinct in its favour”. As the Zapatista spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos says in Ya Basta!, a collection of his essays and writings: “Everyone is dreaming in this country, it's soon time to wake up...”

---------------------------------------------------------

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter