The Syrian regime made plans to use poison gas, including the deadly nerve agent sarin, against potential internal opposition in 2009, two years before the start of the civil war, Mediapart can reveal. Mediapart has spoken to Syrian scientists involved in the country's chemical weapons programme who say that at the end of 2009 the order was given to equip seven military air bases with storage facilities for the chemicals or 'precursors' used to create sarin gas plus facilities to fill bombs or other chemical-bearing munitions.

The same scientists, who are now in exile, also say that in July 2011, just after the start of the civil war and immediately after the first defection of a senior officer from the regular Syrian army, the regime ordered those in charge of chemical weapon production to create small weapons – artillery shells, grenades, rocket warheads – adapted to tactical use as quickly as possible.

The evidence provided by these scientists now makes clear that the Syrian president Bashar al-Assad came up with secret plans to gas his fellow Syrians and equipped the military to do so well before the civil war began. Subsequent events have shown that Assad went through with these plans, even though the use and possession of sarin and other chemical weapons is banned under the 1993 United Nations Chemical Weapons Convention. Syria only became a signatory to this when forced to do so in September 2013.

Even so, despite signing the convention and despite its repeated denials, Damascus regime has carried on using its arsenal of chemical weapons, and in particular sarin gas. A largely odourless and colourless product, which makes it hard to detect, this poison gas can cause death in just a few minutes by paralysing the nervous and respiratory systems. Those who survive exposure to this toxic cloud can be left with serious and permanent damage to the brain. Out of the 300,000 people who have died in the Syrian civil war up to now, chemical gas attacks from the Damascus regime have killed 2,000, with several thousand left injured, according to humanitarian groups on the ground.

The premeditated nature of these war crimes carried out by the Syrian dictator is one of the key revelations obtained by Mediapart from interviews with several Syrian scientists, experts and engineers who were involved in the design and manufacture of chemical weapons, and who are today in exile in Europe or the Middle East. Speaking anonymously, these defectors – some of whom have joined the ranks of the opposition whom they are helping to protect against chemical attacks – have handed over to Mediapart a wealth of new information on the Syrian 'scientific-military complex'. They have given details of the nature and quantity of the chemical weapons still kept by Damascus today, on the origin of the raw materials and the establishments used to produce them, the location of the main sites of research and production, the weapons carriers available to the Syrian military and the methods used to deceive inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the UN.

Some of these experts have explained to Mediapart why they worked for Bashar al-Assad or his father Hafez al-Assad in the first place, and why they later decided to flee their own country. They have also divulged several “manufacturing secrets” which allow other experts to confirm with certainty the Syrian origin of certain gases used by the dictatorship for the last five years. This information could one day be used to help the indictment against Bashar al-Assad and his clan in front of an international court.

For the time being, though, their evidence and their experience are a source of irreplaceable information as to the true nature of the Syrian dictatorship, the character of its leaders and the barbarity of which they are capable. In particular it is thanks to the information handed over by some of these defectors that two months ago French experts were able to identify with certainty the traces of sarin found on the victims of the bombing of the village of Khan Sheikhoun in the province of Idlip in north-west Syria. This latest chemical attack, carried out by the Syrian air force on April 4th, left 88 dead, including 31 children.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Sarin has been manufactured by the Assad family's regime for 30 years and the Syrian version is made according to a standard formula but with a few local adaptations. When the gas is spread in the atmosphere these adaptations result in the presence of two products, diisopropyl methylphosphonate (DIMP) and hexamine. The first of these is a 'secondary product' of producing the gas. The second is a substance used by Syrian chemists to help in the production of the sarin. The presence of the two constitutes the characteristic signature of Syrian sarin. This signature is made easier to detect by the fact that both products remain in the soil for a long time, and also on weapon fragments and in the blood, urine and tissue of victims, where it can be measured in laboratories by electrophoresis or other sophisticated methods of analysis.

It is thanks to this irrefutable evidence, collected on the ground by rescue workers and doctors, and analysed by experts from the French intelligence services guided by information from some of the exiled Syrian scientists, that the foreign minister under the last government, Jean-Marc Ayrault, was able to make public a 'national evaluation' three weeks after the attack on Khan Sheikhoun. This openly accused Syria of having “carried out a chemical attack against civilians on April 4th, 2017”.

Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father Hafez al-Assad in June 2000 and had a reputation of being a modern president who was in favour of opening up political dialogue; the then-president of France Nicolas Sarkozy even invited him to the Bastille Day parade in July 2008. So why in 2009, just a year after that invitation, did Assad decide to turn against his own people the chemical weapons capability that his father had built up and which was officially developed so that Syria could have a deterrent against neighbouring Israel, which has long had nuclear capability?

Assad rattled by Iranian 'green revolution'

“Because he was afraid,” explains one of the Syrian scientists who spoke to Mediapart. “The timing of the eruption of the 'green revolution' in Iran in June 2009 and the orders given to the [Syrian research organisation] Scientific Studies and Research Centre (SSRC) to miniaturise gas munitions as a matter of urgency and to equip seven specially-chosen air bases with storage facilities for sarin precursors [editor's note, i.e. the chemicals used to produce the gas] and with devices to fill munitions clearly shows that he was worried about facing the same kind of popular revolt as [Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad, whose re-election to the presidency of the Islamic Republic, considered fraudulent by his opponents, had brought students and a section of the population onto the streets. Bashar al-Assad knew that social networks had played a major role in this 'Twitter revolution'; perhaps he sensed what was to come two years later? But he was determined to break a popular revolt by any means.”

“The best proof of his panic faced with possible opposition to his regime,” notes one engineer, who also worked for Syria's SSRC, “is that he simultaneously ordered 10,000 tear-gas grenades from Iran and ordered a report on a network of gantries equipped with cameras over the main traffic routes linked to a surveillance centre by high-speed fibre optic cable, and their installation as quickly as possible. If, as the regime said at the time, this was simply to monitor and regulate the traffic, it wouldn't have been necessary to invest in a network with high-definition cameras which allow you not only to monitor vehicles and passers-by but also to recognise faces. And store the data. From the specifications sheet alone some technicians understood the precise nature of the project: to give the regime unprecedented crowd surveillance. Especially as at the same time other departments were receiving the order to draw up and put in place a programme of monitoring all telecom networks.”

The SSRC has been well looked after and closely monitored by both Hafez and Bashar al-Assad and is not, despite what the regime spokespeople sometimes claim, a “Syrian version” of France's National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). Instead, it is a vast scientific-military complex that was created at the start of the 1970s. In theory its purpose is the study and advance of science, but it is much better funded than university science departments, is directly attached to the presidency rather than the education ministry and most of its activity is devoted to the research and development of armaments.

The Syrian army and especially the mukhabarat or intelligence agency keep a tight watch on the recruitment and behaviour of personnel, both inside the institution and outside. The SSRC, which is organised on almost military lines and based around staff with Western training, is divided into five departments. Four of these are identified by numbers: department 1000 (electronics), department 2000 (mechanical), department 3000 (chemical) and department 4000 (aviation and flying machines). The fifth department is the Higher Institute for Applied Science and Technology (HIAST), which is the civilian 'façade' of what is essentially a military complex.

Meanwhile, and independent of the five departments, there is the discreet “Project 99” which controls the concealed offices and production sites of the Syrian Scud missile programme, which are in addition to the liquid-propellant Scuds supplied by North Korea. Each department has its own research centres and testing and production facilities, which are spread around the country and often disguised as civilian installations. Several of these SSRC sites have been identified and located by former staff who have spoken to Mediapart.

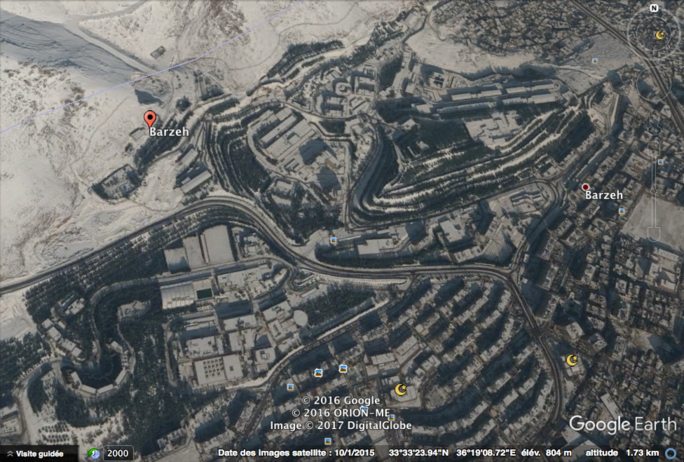

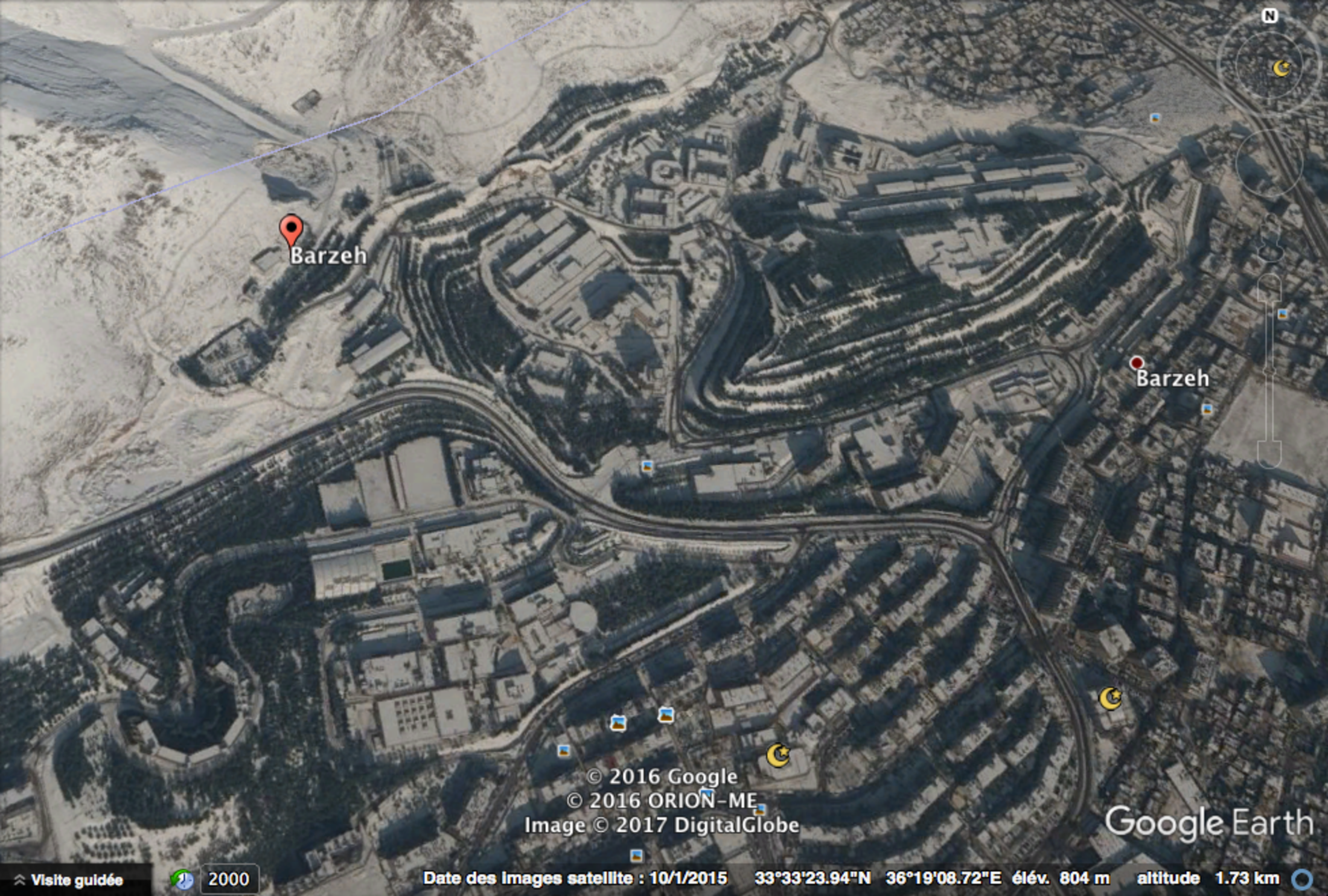

Enlargement : Illustration 2

According to estimates by former staff, out of a total of around 9,000 some 5,500 of the employes at SSRC today work in the aviation, electronics and mechanical departments, developing and producing missiles, bombs and rockets. Departments 1000 and 2000 make electronic items, guidance systems and the heavy launching equipment used for missiles and rockets which are installed on lorries or armoured vehicles. More than 350 people have been assigned to the chemical department which is divided into two branches.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

One of them, 3100, handles research and development into biological and toxicological subjects, polymers and paint with military applications. Inside this section is a unit numbered 3110 which is devoted exclusively to ways to produce chemical weapons and their antidotes, as well as ways to detect them and decontaminate affected areas. Several of the scientists met by Mediapart have worked and/or had senior positions inside this unit.

'I told the head of intelligence we had received an absurd order'

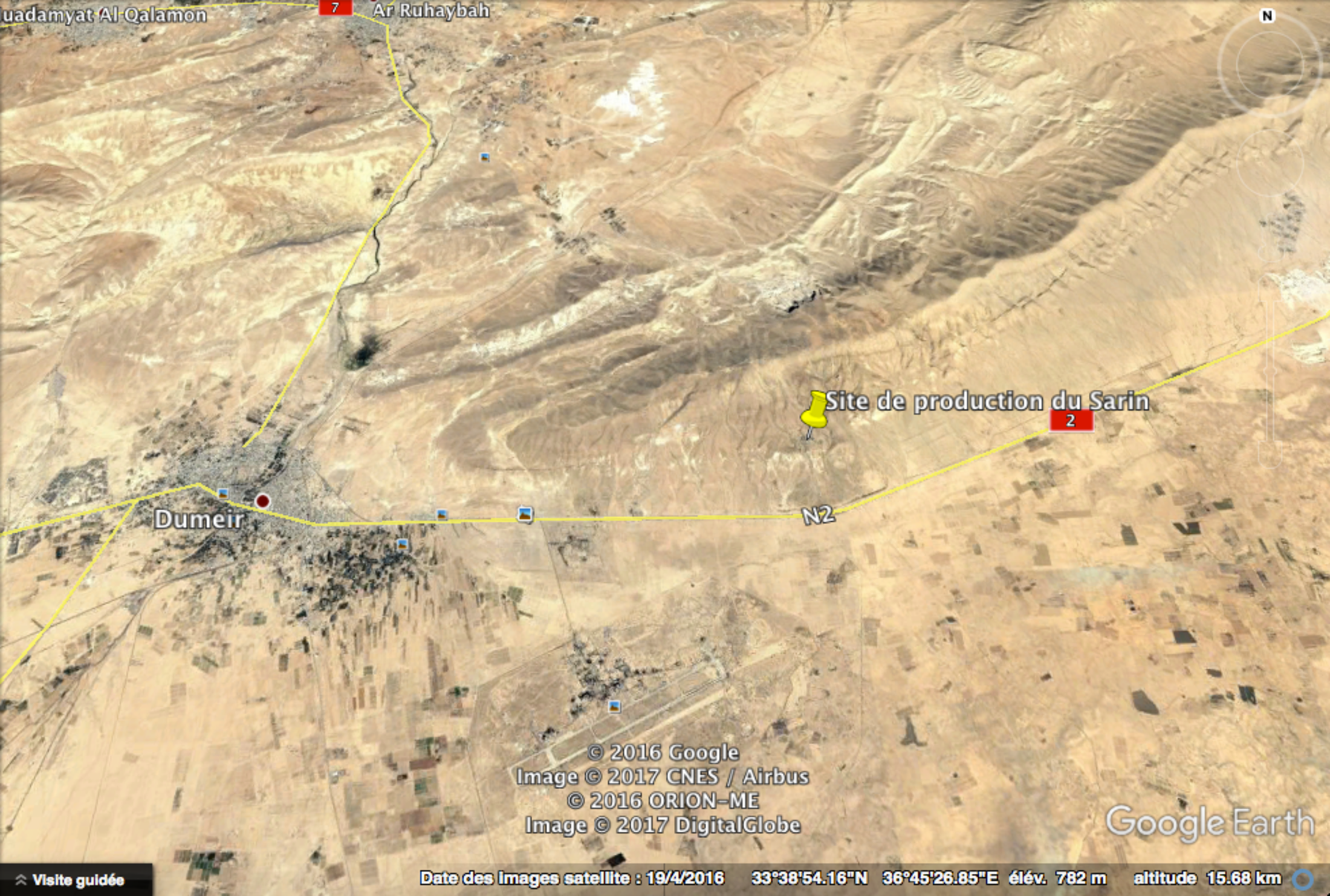

The other branch of the chemicals department, 3600, was in charge of the production of chemical weapons. It had several sites located in the middle of the desert, between 60km and 100km to the east of Damascus, including the historic site of Al Dumayr serviced by route number 2. This site was partially destroyed by the United Nations following the Russian-American agreement on the elimination of Syrian chemical weapons in 2013.

The current director of department 3000 – which to confuse matters was recently renamed 5000 – is called Zohair Fadhloun. Another department 3000 site, at Jamraya on the slopes of Mount Qasioun north-east of Damascus, which assembled and stocked missiles, was attacked twice by the Israeli air force, in January and May 2013. The apparent aim was to destroy devices judged dangerous by the Israeli military or which were on the point of being transferred to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Enlargement : Illustration 5

“Many of the middle managers at the SSRC were, like me, recruited after taking their baccalauréat because of their scientific marks and invited to continue their studies in Syria and then abroad thanks to grants from the SSRC, with the aim of becoming defenders of Syria, on the same level as soldiers, through their contribution to the modernisation of military techniques,” recalls the former manager of a branch within department 3000. “In my view, contributing to providing my country with a strategic asset in the form of chemical weapons meant sheltering it from an attack from Israel, a danger that was presented as – and for many of my compatriots felt to be – a recurring one in Syria. It also allowed the country to negotiate on something more of an equal footing with Israel over recovering Golan.”

The former manager continues: “I knew that a war wouldn't enable us to achieve this objective. I'm not an Alawite [editor's note, an offshoot of Shia Islam to which the Assad family belongs], I had no attachment to the Hafez al-Assad regime, but I considered the president to be a good enough operator to obtain that from Israel, in the framework of a peace agreement or otherwise. So working on the production of strategic chemical weapons, and on a tool of credible dissuasion, with the aeroplanes and missiles capable of delivering our chemical munitions, wasn't a particular problem for me.”

He goes on: “Doubts and problems with it only came when they designated the seven air bases to be equipped, and gave orders to come up with miniaturised gas munitions. The runways of the chosen airports were not long enough to allow a Sukhoi 22 fighter-bomber or Mig 23 fighter from our air force to take off. So they didn't lend themselves to a strategic use of chemical weapons. One of the bases in fact just had helicopters. Another, the one at As-Suwayda, in the south of the country, was so close to the Israeli border that the Israelis could have destroyed it with cannon fire, if they'd noticed it was becoming a threat to them. To give these bases storage systems for sarin precursors and the equipment needed to put it in bombs didn't stack up. There was only one conclusion to be drawn: the government wanted to use this weapon on home soil. In other words, against a potential revolt. I expressed my doubts to my superior. I also warned the head of the intelligence services, Ali Mamlouk, that we had received an absurd order. What I didn't know was that the idea of using sarin against the opposition came from him.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

When, for the first time, chemical weapons were used inside the country, at Kafar Takharim in October 2012, those SSRC employees who had shown doubt, reservations or been reticent, and who had all been relieved of their functions, thought that an international scandal was about to break. They thought that, at the least, the regime would be forced to explain itself and, perhaps, obliged to abandon this strategy. They were wrong. The attack was of a limited scale and the majority of the first victims were opposition fighters. The diplomatic repercussions were derisory. And Bashar al-Assad understood that by taking a few precautions, which in the end and over time he was able to get away with, he was able to continue with his decision to gas his opponents. But the witnesses to the premeditated nature of his crime, especially those who had produced the weapons and voiced their disagreement, had become a problem.

It was around this time, in September 2012, that one of the heads of the chemical weapons programme, Bashar Hamwi, was bundled away by the intelligence services from in front of his office at the SSRC. 'Since then there's been no sign of life,” says one of his former colleagues. “But the miniaturised weapons on which he was working have been made and used on many occasions since his disappearance. It's not impossible that he is, still today, being held prisoner and forced to continue his work in secret in exchange for the safety of his family who have been taken hostage.”

Scientist's name leaked onto the web

At about the same time as Hamwi's disappearance, another executive from department 3000, who had been relieved of his duties after indicating his disagreement with the regime's orders, discovered that his name had appeared in online forums which were denouncing the makers of poison gas and calling for them to be eliminated. “Rather than dispose of me, the regime made my name public, doubtless hoping that I would be eliminated by the opposition,” the executive says today. “I realised that it was better, for me and my family, to leave the country. I had friends in the opposition and relatives in the Gulf and Europe. I left.”

Despite several defections the chemical weapons department of the SSRC, which does not report to the army but the aviation branch of the mukhabarat, has continued to work on adapting sarin for use on home soil, and coming up with miniaturised munitions adapted to this task and delivering them to the air force.

Until 2008 the chemical weapon ingredients or precursors were stored by two units of the aviation branch of the mukhabarat, unit 417 and unit 418. After an accident linked to a group of soldiers who embezzled part of the budget earmarked for storage security, an officer called Gaith Ali and around 20 other soldiers were transferred.

These units were then directly attached to the SSRC and became “branch 450”, and given responsibility for stockpiling the chemical weapons, with that task split between branches 451 and 452. In doing so the government thought it could reduce the level of corruption that was rife in the army, but from which the SSRC was largely spared. The monitoring of the institute responsible for chemical weapons and the secrecy around their use on home soil was stepped up still further. The senior officer who was formerly in charge of chemical weapons in the 5th Army Division, General Zaher al-Saket, later told Al Jazeera news that his candidacy for the post of commandant of unit 451 had been rejected in favour of Colonel Mohammad Ali Wannous, who is an Alawite and thus judged a safer candidate than a Sunni.

In July 2011, just as the Free Syrian Army was being established by senior officers who had defected, the regime's unit 450 started filling the storage tanks on the designated air bases and helicopter squadrons began to receive their first sarin grenades. In October 2012, as the uprising became more militarised, observers said there was a “strong presumption” that sarin had been used by the Syrian army at Kafar Takharim and and Salqin, 60km west of Aleppo. It was a similar story in November at Harasta, near Damascus, and at Homs in December. According to an inventory in “Allégations d'emploi d'armes chimiques” ('Allegations of chemical weapons use'), a report compiled by the French external intelligence agency the DGSE which was annexed to the French Foreign Ministry's 'National Evaluation' this April, poison gas has reportedly been used 130 times in Syria between October 2012 and April 2017, against targets controlled by the opposition. They have involved attacks both on positions held by fighters and civilian targets.

Around 20 of these chemical weapon attacks took place before the Russian-American agreement in September 2013 on the destruction of Syrian chemical weapons, and before Syria signed up in the same month to the United Nations Chemical Weapons Convention. All the other attacks have taken place afterwards. This not only confirms its clear contempt for the law, but above all the Damascus regime's utter cynicism. This contempt and cynicism were first bolstered by the inaction of the international commitment, then by the decisive military and diplomatic support of Syria's ally Russia.

According to the DGSE document three quarters of the allegations of chemical weapons use by the Syrian regime could not be characterised as “greatly reliable” by the French intelligence services, but in two cases there was a “strong presumptions” that sarin had indeed been used, while in 22 cases there was “strong presumption of the use of chlorine”. In five other cases, which occurred at Aleppo, Jobar, Saraqeb in April 2013, at Damascus in August 2-13 and then at Khan Shaykhun on April 4th, 2017, the “use of sarin was proven by France”. In the same period three mustard gas attacks, at al-Hasakah in June 2015, then at Marea in August and September 2015, have been blamed on Islamic State which retrieved old stocks of poison gas from the Iraqi army, especially in Mosul.

During one of the sarin attacks proven by the French intelligence services, at Saraqeb, a Syrian army helicopter dropped three grenades of the same type on districts in the east of the town. The first exploded and released its load of sarin gas without harming anyone, the second one caused one death and injured about 20 people. The third, which did not explode, was retrieved by the French intelligence services. Analysis showed that it contained “a solid and liquid mixture of around 100 millilitres of sarin of a purity estimated at 60%. Hexamine, DF [editor's note, for Methylphosphonyl difluoride], DIMP have also bern identified”: the chemical signature of department 3000.

The use of a helicopter, the nature of the munitions and the analysis of the recovered chemical components all clearly point, beyond any doubt, to the Syrian regime. The “red line” drawn in August 2012 by US president Barack Obama had already clearly been violated. And this without provoking any major reaction. Four months later the massacre at Ghouta near Damascus took place in which many hundreds died as a result of a chemical attack.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter