The jewel of Kazakh sport is once again taking part in the Tour de France which began in Germany on Saturday July 1st and which will then weaves its way across France until it concludes at Paris on July 23rd. The Astana cycling team – it takes its name from the capital of Kazakhstan – exists to bolster the image of that country's dictatorship. Run by former cyclist Alexander Vinokourov, its team outfit bears the national colours adorned with a badge depicting a steppe eagle beneath an image of the sun.

But behind the turquoise blue of the team jersey there is the reality known to all cycling fans: that while the team is indeed financed by Kazakh sovereign funds, it is in fact based in Luxembourg. It is there that the company Abacanto, which owns the team's professional cycling licence, has its headquarters and pays its riders, and where it has existed in complete legality since its creation in 2007, in a country known for its low taxes. In the world of cycling, they are not alone in having made this choice.

Mediapart has discovered that there is a growing tendency among riders to take advantage of Luxembourg's favourable tax system. A handful of cyclists have established themselves there full time, but most use tax trusts to receive profits from the sale of image rights in an arrangement that is legal as long as the income is declared to the tax authorities.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Alain Gallopin is an important name in French cycling. He was himself a professional rider for just three months before suffering a serious accident in 1982 and has since had a successful career as a trainer. Today he is sporting director of the Trek-Segafredo team (part of the elite World Tour) and in the past he has coached some of the biggest names in cycling such as Jan Ullrich, Fabian Cancellara, the Schleck brothers Andy and Fränk, and Spaniard Alberto Contador.

In 2008, when he was part of Astana, he set up his first company in Luxembourg, called Milnown Lux. “At the time it was the team who suggested this set-up. I'd also heard it spoken about here and there,” he told Mediapart. Gallopin says he received “the equivalent of 30% of my salary in image rights in Luxembourg”. The rest of the money was paid in France. “The arrangement suited everyone,” says Alain Gallopin. The cycling team had to pay less in employer social contributions while the profits on his Luxembourg company were lightly taxed. This is because Luxembourg has opted to exempt from tax 80% of income from intellectual property and from selling intellectual property rights. This means that the effective tax rate on intellectual property rights is less than 6%.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

As a partner and manager of Milnown Lux, Alain Gallopin received around 70,000 euros in dividends and paid just a few hundred euros in tax. What is not clear is what the tax rate was once this money was taken into France. The French cycling trainer says he does not know much about the subject and merely says that “it was all declared to the tax authorities”. He closed the company in 2014. “Today all my business activities are in France, it's much clearer like that. In the end I didn't gain a lot, almost nothing, I think it's mainly worth it for huge salaries,” he says. Then he adds: “It's the firms who deal with all that who profit from it most of all.”

The company involved in Alain Gallopin's tax arrangement was International Tax Consult (ITC). Run by the Flemish accountant Jan Vanden Abeele - who did not respond to Mediapart's questions having asked for them in writing - it describes itself as a “leader” in international tax affairs. “We help clients all over the world solving problems that arise in relation to international taxation in a broad sense,” the firm says on its website. Since 2005 it has helped dozens of sports people reduce their tax payments, starting with Belgian cyclist Johann Bruyneel, one of the first in his sport to use Luxembourg's tax system in this way. Bruyneel, who was sporting director for the later disgraced American cyclist Lance Armstrong at the US Postal Service team (later known as the Discovery Channel team), owned two companies there.

The first of these was 2.IN BVBA & Cie, founded in 2005; the second was Lockdale Lux, set up a year later in 2006. Both were dissolved after Bruyneel retired in 2012. Between them they handled a turnover of close to 10 million euros, allowing Bruyneel – who was resident in Spain then the UK – to pocket significant dividends. Lockdale Lux also benefited from a mysterious shareholder bearing the same name (Lockdale Limited) and based in Cyprus, where ITC have a branch. Mediapart was unable to find out who was behind this additional structure

The same set-up was duplicated for other riders and team managers: the Slovene Janez Brajkovic, Carlos Barredo from Spain, Irishman Philip Deignan, Australian Allan Davis and the Belgian sporting director Lorenzo Lapage. None of them wanted to talk to Mediapart. Even the Belgian mechanic Chris Van Roosbroeck had his own Luxembourg shell company whose business aim was the “utilisation of intellectual property, with a speciality in the technical support of a team of professional racing cyclists”. According to documents seen by Mediapart some 120,000 euros had accumulated in the company up until 2013. Contacted by telephone Van Roosbroeck said: “I've nothing to say about all that.”

The Italian cyclist Ivan Basso, who has twice been on the podium in the Tour de France, also benefited from an identical tax set-up. In 2007 his company Roksper Lux amassed 460,000 euros in revenue but says it paid just 3,820.53 euros in income and business tax. It paid out more than 320,000 euros in dividends that year. Basso declined to speak to Mediapart.

Belgian tax authorities in prusuit of tax fraud

In Belgium, meanwhile, one case has already caused concern in the cycling world. It involved Dirk Demol, a former rider who became a sporting director, who came under the spotlight for alleged tax fraud in 2013. He, too, was an ITC client and had a company in Luxembourg and another in Cyprus. The Belgian newspaper that broke the story, Het Nieuwsblad, mentioned the tax arrangements in broad terms. In fact, Demol became the partner and manager of the company Rivista Lux when he arrived at Astana in 2009. He continued to benefit from it when he took control of the Radio Shack cycling team. Dirk Demol refused to discuss the situation with Mediapart. “I don't want to speak of anything other than sport,” he said. Rivista Lux was abruptly dissolved in 2014. As for his tax affairs, Demol simply said: “Everything's been brought back to Belgium.”

In a separate case Patrick Lefevere, manager of the Quick Step team and also an ITC client, reportedly reached a deal with the tax authorities in Belgium in April this year after they looked into his affairs. “It does not however involve an admission of guilt … there was never an intent to hide,” his lawyers told Belgian journalists, without divulging the amount involved in the deal.

Lefevere acted in order to halt proceedings by the Belgian authorities, who suspected him of not having declared bonuses and revenue from image rights. Several riders in his team had already done deals with the authorities. One was sprinter Tom Boonen – four times winner of the Paris-Roubaix race - and another was twice victor of the Tour des Flandres, Stijn Devolder. As their names do not feature in the ITC documents seen by Mediapart it is possible that they received their bonuses directly and not via a Luxembourg company. Neither they nor Lefevere responded to questions from Mediapart.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

However, the omnipresent tax advisor Jan Vanden Abeele was involved with another leading cyclist, the 2012 world champion Philippe Gilbert whose fame reaches beyond the world of cycling. Elected Belgian sports personality of the year in 2009, 2010 and 2011, Gilbert moved to Monaco at the end of 2008. The cyclist, who was on the way to becoming lead rider at the Lotto team, had at the time praised the topological appeal of the region. The valleys and climate provided him with an ideal training area, he said. But how did his justify his involvement in Luxembourg?

In March 2009 Gilbert set up the Luxembourg-based company Urizal Lux, of which he held a symbolic stake along with the Cypriot company Urizal Limited which held 99%. In December 2010 the cyclist handed the arrangement over to his agent Andrew McQuaid, son of Pat McQuaid who was president of the world cycling governing body Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) between 2005 and 2013. At the time Urizel Lux changed its name to become Trinity Sports, the name of Andrew McQuaid's sports agency. The company has continued to turn over several tens of thousands of euros a year. Dividends are sent to Urizal Limited in Cyprus, though we do not know what the ultimate destination of the money is. Neither Andrew McQuaid nor Philippe Gilbert responded to Mediapart's questions.

It seems that setting up companies abroad is less common practice in French cycling itself. “None of the around sixty French racers whom I advised had a company abroad,” says Michel Gros, a leading agent for cyclists, who has just stood down at the age of 74. This is probably explained by the fact that French riders do not often join foreign teams. However, there are some examples.

Tony Gallopin, nephew of Alain Gallopin and a cyclist with the Belgian Lotto-Belisol team (now the Lotto-Soudal team), has had recourse to tax structures in Luxembourg, involving ITC, Cyprus and Luxembourg itself. Tony Gallopin says: “It was at the time I was with [cycling team RadioShack–] Leopard and the team was from Luxembourg. Like all cyclists we can have a third of our salary via a company. When I started to earn bigger salaries at that time it was advantageous for the team to pay a part of our salary in image rights.”

But today the cyclist – who moved to his current team in 2014 – insists he no longer has a company in Luxembourg. Indeed, Mediapart traced his company Olmitara to Nyon, ITC's Swiss address. “I have a salary contract and a contract for image rights. I'm an employee in Belgium, it's just the image rights that are over there,” says Tony Gallopin, who lives south of Paris and who insists he doesn't know the reason why the company switched country. “Why did we go to Switzerland? That's a good question. Doubtless because it was difficult in Luxembourg and Switzerland simplified something.” His company has since earned tens of thousands of euros. The rider insists that he has not touched the money, which is not declared in France, except for “organising training courses and meetings with journalists”.

Mediapart's investigation has also come across affairs of the past, some of which were shielded from the media and especially tax investigators. For example, one name that cropped up was that of the Festina cycling team which was linked to a doping scandal at the Tour de France in 1998. At the time agent Michel Gros was the deputy sporting director for the team. “The sporting entity was domiciled in Andorra, the sponsor was Spanish and the riders were paid in their country, in relation to their contracts,” he says.

But the riders also earned various bonuses and image rights payments directly in Andorra. “It was called an additional salary but that was all bogus. It was simply about paying lower [social] charges on a part of our salary,” says a former Festina rider who benefited from a system he says he was “offered on my arrival in the team”. In his case this part of his income amounted to around 15% of his net salary. “We didn't declare this money,” he says. For him, using this hidden money in France was straightforward. “I had a bankcard on this account. The advice given in the team was to use it through withdrawals of 300 euros a time. To do the shopping, fill up the car or go to a restaurant.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

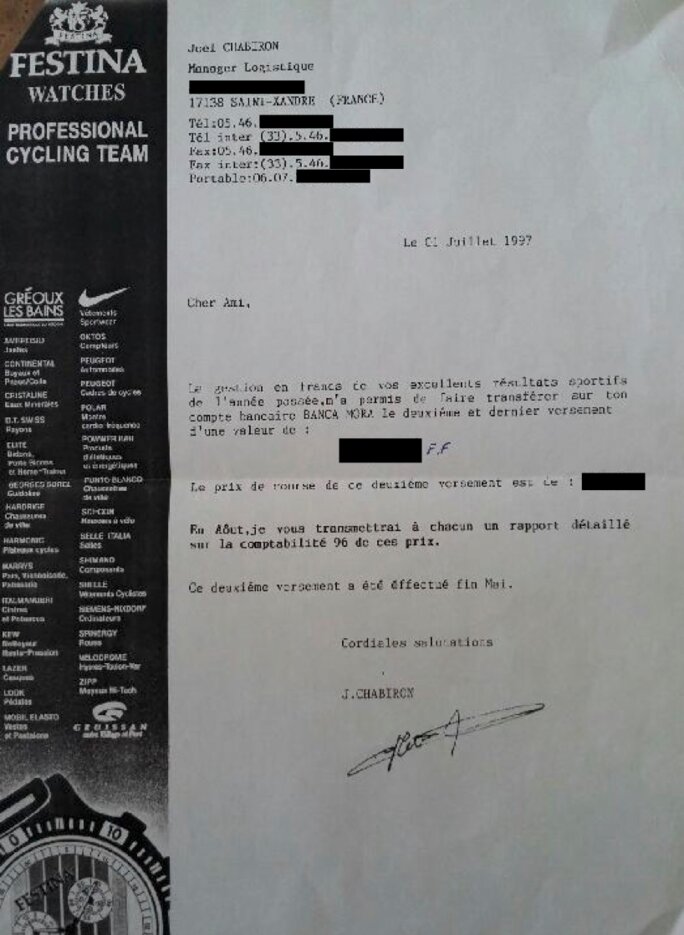

A teammate, who also asked not to be named, says: “In my case I withdrew the money directly in cash from my dedicated account when I went to do the shopping with my wife in Andorra.” As proof this well-known former rider sent Mediapart a letter signed by the late logistics manager at Festina, Joël Chabiron. In this pro-forma letter (see above), which was clearly aimed at several of his riders, the team official announced in July 1997 the transfer of the “second and final annual payment” linked to the “excellent sporting results of the past year”. The money was sent to the rider's account at Banca Mora, the same Andorran bank used for the team's accounts.

Festina's unorthodox practices led its former sporting director, Bruno Roussel, to be convicted of “tax fraud” and “accounting omissions”. On appeal, the court of appeal in Lyon upheld his sentence of a six-month suspended term of imprisonment and a 10,000-euro fine.

In 1998 Roussel also told a judge investigating the discovery of the banned performance-enhancing substance EPO in a car belonging to one of its team members that the money in Andorra allowed banned products to be bought in complete secrecy. “At the request of several riders and with the agreement of the team of which I was a member … we put in place a system which involved distributing and importing doping products,” he said at the time, mentioning the sum of 400,000 francs (just under 61,000 euros) used for buying these products via their Banca Mora accounts. On this evidence it seems that tax havens were used in this case not just to reduce the amount of tax paid, but also helped to hide the purchase of banned substances.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter