Opening its archives and admitting to some of its colonial crimes, as it has done with Algeria, Cameroon and Senegal in recent years and perhaps soon with Madagascar, is something Emmanuel Macron’s France is capable of, to a certain degree at any rate. But not always, and certainly not with just anyone.

An example of its reticence concerns the West African nation of Niger. Members of some communities there are the direct descendants of victims of the French military's 'Central African Mission' - also known as the 'Voulet-Chanoine Mission - which spread terror along the route to Lake Chad in 1899. These communities have approached the French government looking for an acknowledgement of those past wrongs and for compensation, but have so far been met with a flat refusal.

In a response dated June 19th, and sent to several United Nations rapporteurs who had relayed the complaint from Niger in an official letter two months earlier, French diplomats made clear they would not grant the various requests, save for one small concession; the possibility of returning objects looted during that campaign of conquest.

“France remains open to bilateral dialogue with the authorities in Niger, as well as to any collaboration regarding research on provenance or on heritage cooperation,” the letter states in conclusion. But the French authorities make clear they have no intention of responding to other demands: there will be no memorial rehabilitation, no reparations and no financial compensation.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The UN rapporteurs had asked France under the “mandates entrusted to us by the Human Rights Council” to provide information on steps taken by Paris to establish the “truth of the facts”, and also to “issue a public apology”, to offer reparations to victims and to “inform the wider public”. But France responded with vague remarks that barely concealed its inaction, while invoking the non-retroactive nature of international agreements cited by the complainants, which were signed long after 1899. It also referred to the accusations from the communities in Niger simply as “allegations”.

Diplomatic breakdown

“There will be no follow-up, there's no obligation for us to do so,” says a diplomatic source. “On memory issues,” adds the source, “you need a bilateral dialogue.” Yet this dialogue was broken off after an army faction seized power in the Niger capital of Niamey on July 26th 2023. Since then, French soldiers have been expelled from the country, as has the nuclear giant Orano, and France's embassy there is now closed .

At France's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, officials suggest that such dialogue will only be possible again once the ousted president, Mohamed Bazoum, is freed along with his family. This “friend” of France has been held captive by the junta for two years now. Paris also continues to call for a “swift return to constitutional order”.

“Apart from France saying it's open to dialogue, there's nothing satisfactory in this letter,” laments Hosseini Tahirou Amadou, a leading figure in the Groupe de communautés du Niger pour la justice réparatrice de la colonisation, a collective which speaks on behalf several communities from half a dozen towns ravaged by the 1899 military mission. “It doesn't even admit to [France] having committed a crime, even though everything is documented, in particular by French officers!” he says.

Deployed in January 1899, the aim of the Central Africa Mission was to seize territories east of Lake Chad before the British, Germans or Turks could get there. It was led by two officers, Captain Paul Voulet and Lieutenant Julien Chanoine, who had already “distinguished” themselves a few months earlier during the brutal occupation of the Mossi kingdom (in what is now Burkina Faso). These people, Chanoine wrote at the time, were “barbarians who only understand force”.

Massacres

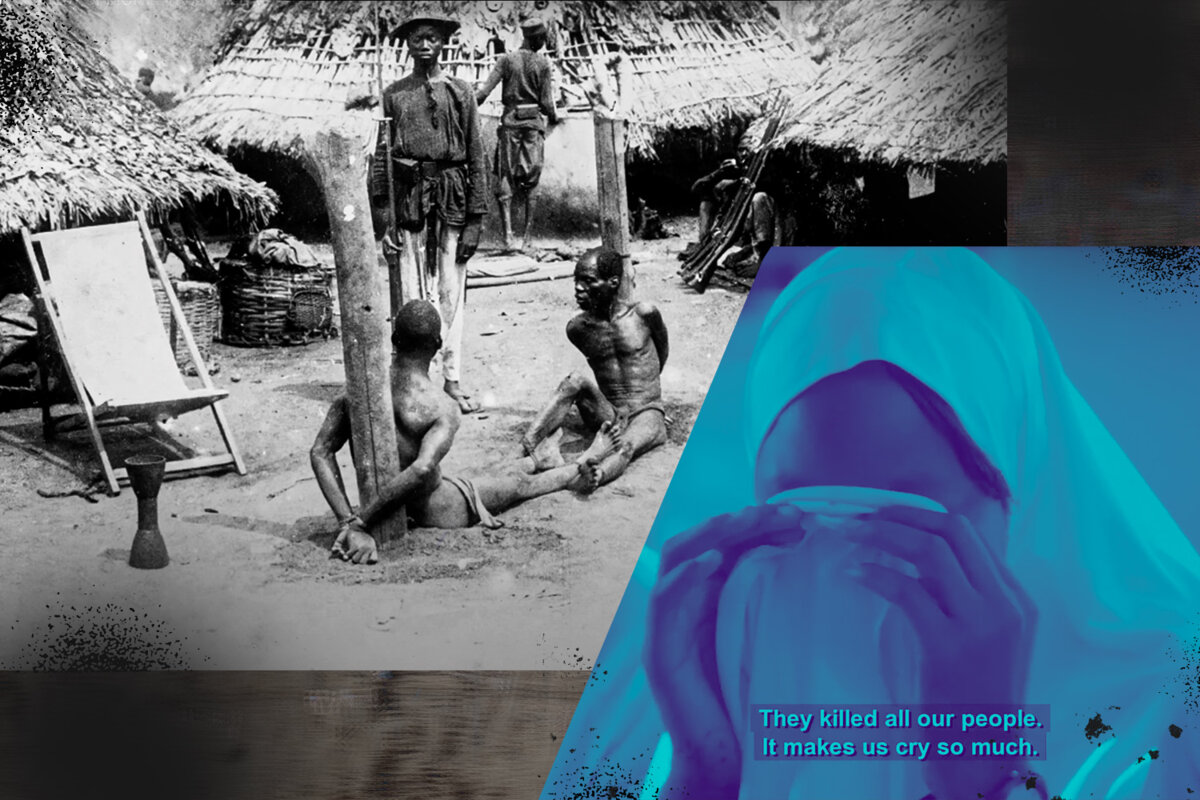

From the moment it began its march in what is now western Niger, this large column, made up of around 1,700 people (including eight Europeans, 600 African riflemen, 800 porters and between 200 and 400 women, some of them enslaved for sex), displayed extreme violence, both to subdue resisting locals and to obtain food, slaves and women. The troops lived “off the land”, in the words of soldiers quoted by historian Camille Lefebvre in her book 'Des pays au crépuscule. Le moment de l’occupation coloniale (Sahara-Sahel)' ('Countries at Dusk: The Moment of Colonial Occupation (Sahara-Sahel)') published by Fayard in 2021.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The massacres followed one after another: on January 9th 1899 at Sansané Haoussa, the 17th at Liboré, the 25th at Hamdallaye... The column left behind burnt-out villages and butchered corpses. By mid-February, in Dioundiou, 300 people were killed and the town razed. In Lougou, resistance led by the local queen Sarraounia Mangou was bloodily put down. On May 9th came the worst slaughter, in Birnon Konni: at least 1,000 dead, and hundreds of women and girls abducted. The killings continued in Libiri in June and in Koran-Kalgo in July.

“The enemy held out despite deadly artillery. A small village of 600 people. The assault cost us 2 killed, 14 wounded. All the inhabitants killed, village torched,” reported the French after the “capture” of this last place.

“Thousands of men, women and children were killed, tortured, forcibly disappeared, raped, mutilated, enslaved, forcibly displaced and dispossessed during the campaign,” says the collective group in Niger, while noting that it is impossible to know the exact number of victims.

But this was nothing unusual, points out Camille Lefebvre. “The violence of the Voulet-Chanoine mission was merely an amplified version of standard practice” at the time, she writes. “Huge columns feeding off the land, abandoning the wounded and sick on the road, shooting deserters, opening fire on civilians, shelling and burning villages, these were all recurring phenomena.”

This time, though, damning reports made it back to Paris and provoked a reaction. In April, Lieutenant-Colonel Jean-François Klobb was ordered to catch up with the column and take command. As he followed their trail, he found destroyed villages and traumatised survivors. “Grim scenes,” he wrote. But when he reached the head of the column, he was executed.

Three days later, Voulet and Chanoine were killed by their own men, who had also been subjected to a reign of terror. The mission continued under new command. And France granted itself impunity: despite the uproar “back home” and the opening of an army probe, no officer was ever tried, and no public apology was ever made.

The “excesses” of the column were blamed on two madmen who had overstepped their orders. This was a way to snuff out any wider row about the systemic violence of colonial conquest, says Camille Lefebvre.

Rediscovery

Like many in Niger, Hosseini Tahirou Amadou knew little about the crimes of the Voulet-Chanoine column when he met the British filmmaker Rob Lemkin in 2014. Amadou was teaching history in Dioundiou, one of the towns ravaged by the French. Lemkin was making a documentary for the BBC, 'African Apocalypse', on the mission. “I learnt a lot of things I hadn’t known, things many people in Niger didn’t know. That’s when the idea for legal action came to us, and we filed it in 2021,” he says.

Yet this colonial episode is extensively documented. Camille Lefebvre points out that the file on the issue in the French national archives runs to over a thousand pages. She adds that several historians, both from France and Niger, have studied the case, and it has long since broken out of the academic domain, with novelists and filmmakers drawing on it.

In France, “this case returns to the spotlight now and then, in 1899, the 1930s, the 1970s… But it vanishes again just as quickly and is forgotten,” says the historian. While it is briefly taught in primary schools in Niger, it is ignored in France. In secondary schools “they teach decolonisation - and even that only briefly - but much less so colonisation, due to a lack of time and crowded curricula,” she laments.

Like Lemkin in his documentary, Lefebvre notes that the violence of the column caused “deep trauma” in the affected regions. “The legacy of the violations suffered has extended beyond the physical and psychological harm done to direct victims, to include serious material damage and intergenerational trauma affecting their descendants,” writes the complainants’ collective.

They say this legacy can only be overcome with bold measures. “We must restore the memory of these crimes by making them known,” insists Hosseini Tahirou Amadou. “But these crimes should also be made amends for, by returning the stolen objects for example, and there must be financial compensation in one form or another.” Despite France’s response, he has not lost hope. “We want the Niger government to raise the issue at the next United Nations General Assembly [editor's note, scheduled for September],” he says.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter