For the French authorities, the problem of what to do with the estimated 6,000 migrants living in Calais in one of Europe’s biggest shanty towns, and who largely have no intention of settling in France, has become acute since the recent security lockdown at the port and Channel Tunnel entrance has seen clandestine crossings to Britain virtually cease.

As a consequence of the beefing up of security, at a cost of millions of euros, those migrants arriving in Calais are no longer replacing others who have left, and their total numbers in the northern Channel port are swelling.

“The minister told us ‘zero crossings’,” said David Skully, head of the French border police, during a visit to London by interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve on November 2nd to meet with his British counterpart Theresa May. “It’s zero crossing. Above all, in the tunnel, the ability to get through like that is virtually nil today.”

Cazeneuve and May signed an agreement to step up cooperation on measures to reduce illegal immigration, and in a statement released on November 9th the French embassy in London said the “coordination is bearing fruit: since October 25th, no illegal migrants have entered the UK via the Channel Tunnel, and attempted intrusions have fallen by some 90% in 10 days”.

In less than a year, the number of migrants living rough in Calais has doubled, and the sanitary conditions in what is dubbed ‘the new jungle’ – the makeshift camp of tents and shacks on wasteground – has become a national shame.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

By transforming himself into a zealous border guard for Britain, Cazeneuve has created what he himself has described as one of the continent’s biggest “fixation points”, as Europe faces up to the biggest flux of refugees since the end of World War II. The French government must now find a way of managing a problem which it is partly responsible for.

On the day of Cazeneuve’s visit to London, November 2nd, the administrative tribunal in nearby Lille, pronouncing judgment on a lawsuit lodged by NGOs and six migrants over the desperate situation within the Calais ‘jungle’, ordered the French state to improve conditions within eight days or face a daily fine. “For reasons of a manifestly inadequate access to water and toilets, and the absence of the disposal of rubbish, the population of the camp is confronted with an insufficient regard of its elementary needs concerning hygiene and drinking water and finds itself exposed to the danger of insalubrity,” read the judgment. “Its right to not be submitted to inhuman and degrading treatment has thus been gravely and manifestly infringed.” The court ordered the State to provide ten more points of access to water on top of the existing three, the creation of 50 latrines, the cleaning of the site and the creation of a regular a system of rubbish clearance, and to provide a permanent access entrance for emergency services.

The move, however welcome, appeared to be a case of too little too late. NGOs providing assistance to the migrants in Calais, including the Secours Catholique and Médécins du Monde, have been warning of the desperate situation there since the massive flux of new arrivals began in the spring. Prime Minister Manuel Valls only visited the site at the end of the summer, when, on August 31st, he announced at last that hard-surface shelters would be provided to house migrants. But again, the project falls short of meeting demand: just 1,500 people will be accommodated in the container-like cabins which will be available as of January 2016.

On October 21st interior minister Cazeneuve visited Calais - one of seven trips he has made since taking up his post in April 2014 – and announced a three-pronged plan to deal with the crisis there. One was a project he said would be “to humanise” the makeshift camp, while another was to deport to their home countries those migrants “who do not have the intention of settling in France”. Finally, the third was to displace a section of the migrant population to other parts of France in order to relieve the crisis locally.

Cazeneuve, who will have been aware of the open letter deploring the conditions of the migrants published in the daily Libération on October 20th and signed by 800 people largely from the world of entertainment, pledged to provide tents for 400 women and children, half of which would have heating resources. Some of these were made available this week.

He also announced that, in coordination with the health ministry, a doctor, a psychologist and a physiotherapist would serve the camp (all three chosen among medics who are reserve volunteers for Eprus, a public agency that provides assistance in major catastrophes in France and abroad). The medics are to help increase the numbers of consultations managed at a medical day-centre opened in January close to the ‘jungle’, where migrants can also seek preventive assistance such as vaccinations and contraceptive supplies.

However, the measures presented by Cazeneuve, who has received several alarming official reports on conditions in Calais (see here, and here) were largely considered by NGOs and volunteers involved daily in bringing assistance to the migrants as insufficient to provide significantly relief of the often overwhelming demands they face.

The interior minister has also ordered an increase in the numbers of police present in Calais specifically to deal with the migrant crisis, bringing the total of gendarmerie and CRS officers to 1,760 (of which 1,125 are in riot police squads), representing a ratio of one officer for every six migrants. Increasing security around the ‘jungle’ is notably in response to thefts and assaults within the camp itself, as well as attacks carried out on migrants by people from outside the camp. But there have also been cases, some caught on camera, of police officers using untoward violence against migrants.

Migrants displaced 'at the cost of their freedom and dignity'

The displacement of part of the migrant population in Calais principally involves those from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Eritrea and the Sudan. Over the past few weeks, several hundred migrants (600 according to one NGO, the CIMADE) have been moved to holding centres at different sites around France in groups of about 50 people. Most of them cannot by law be deported from France because they have fled countries gripped by civil war, instability and repression. But they are placed in the holding centres even though the authorities are well aware that the justification for their restricted freedom should be that they are subject to deportation. It was for that very reason that a magistrate in Nîmes, in southern France, last month ordered the release of 46 migrants being held locally in one such centre to where they had been sent from Calais.

That prompted the French magistrates’ union, the Syndicat de la Magistrature, to issue a strongly-worded statement (available in French here) condemning the government’s improper use of the system, calling the case “revelatory of a cynical management of what can be called the migratory crisis, which leads a government, in order to give credit to its policies and the communications that surround them, to displace women and men by their hundreds, like pawns, at the cost of their freedom and also their dignity”. The statement concluded by urging the government “to adopt the path that is more responsible and respectful of a state of law, which consists of meeting through action its requirement to satisfy the elementary needs of migrants who it prevents from freely circulating”.

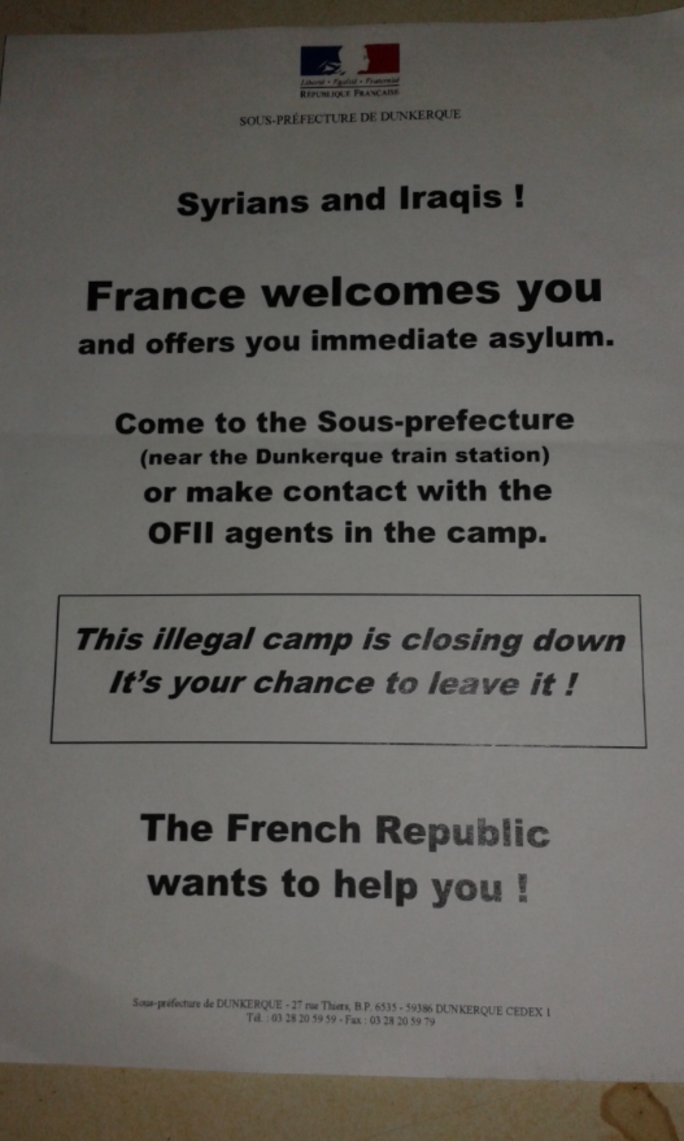

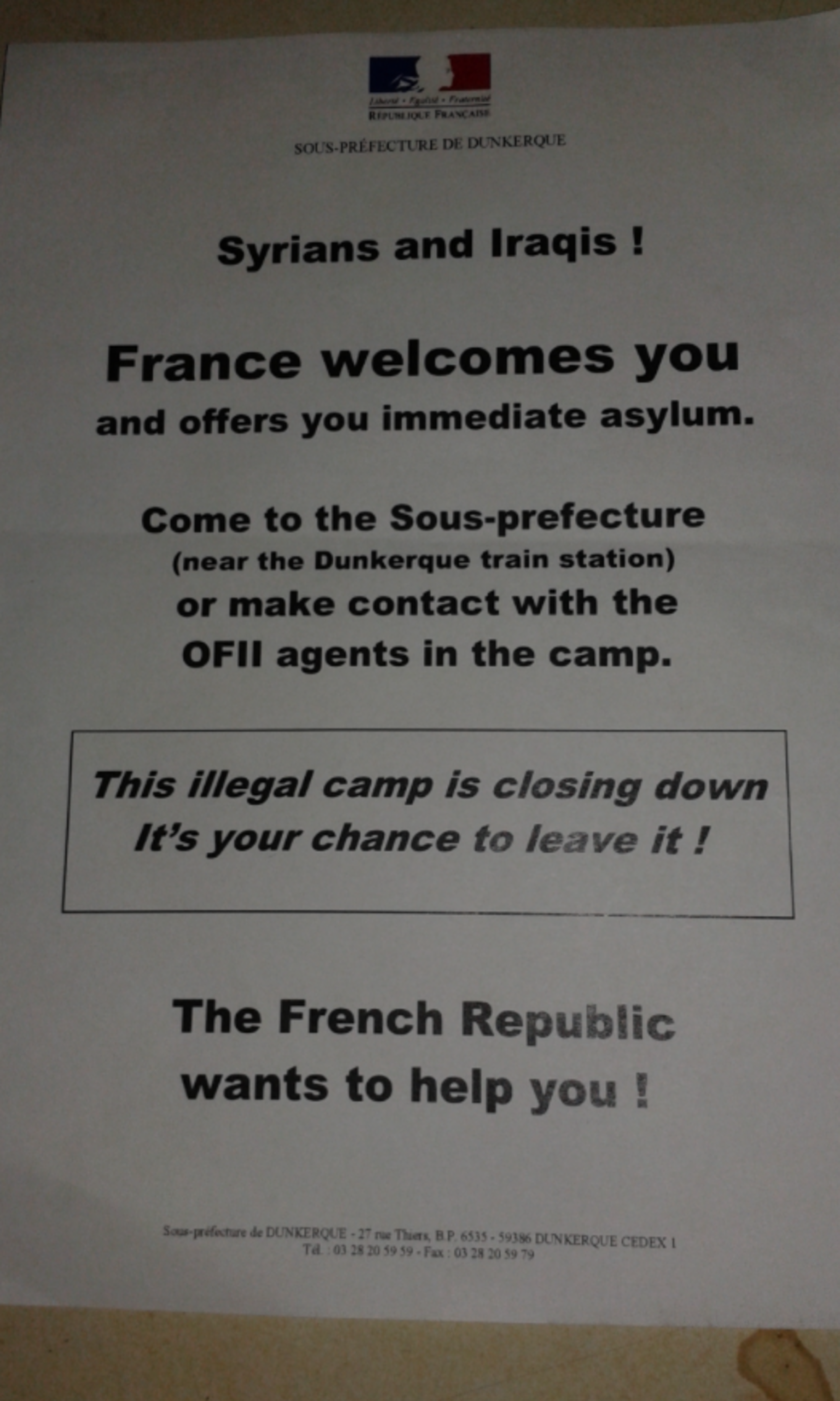

Enlargement : Illustration 2

France is so far down the list of preferred destinations among the flux of migrants entering Europe that it finds itself in the unusual situation of inciting refugees to apply for asylum. On top of the dispersal of groups of migrants to the detention centres, another strategy recently employed is the offer of accommodation for up to 2,000 people in lodgings sited well away from Calais on condition that they agree to apply for asylum in France. The proposal is presented in flyers distributed around the camp (see left). Alongside this, the local prefecture is offering migrants in the ‘jungle’ one month’s free accommodation in other regions on condition they agree to give up with trying to cross into Britain – a commitment that has no legal foundation.

“We want to offer a moment of respite in stable and reassuring conditions, so that each person can reconsider their projects,” said Cazeneuve during his trip to Calais last month. The authorities claim that since October 27th about 850 migrants have agreed to leave Calais for the temporary lodgings financed by the state. Some of them have been housed in Istres, close to Marseille in southern France, while others have been sent to La Guerche-de-Bretagne, close to the Breton capital Rennes in the north-west of the country. All around France, local prefectures – regional centres of state administration – have been lobbying mayors to assist in the project to re-house the Calais migrants. The move follows the government campaign in September to convince mayors to free up accommodation as part of France’s pledge to offer refuge to some 30,000 mostly Syrian and Eritrean migrants currently in European transit centres.

Jean-François Corty is director of French missions for Médecins du Monde (Doctors of the World), a French-based NGO that has long been active in providing medical assistance to the migrants in Calais. He said he considers the dispersal programmes which offer migrants the chance to leave behind the mud and insalubrity of the ‘jungle’ are a positive step. “The state has taken up the idea which we proposed, with other places of initial refuge,” he said. But he cautioned that it remains to be seen what the follow up will be.

For it is unclear what will become of those migrants who have accepted one month’s “respite” accommodation, and whether they will simply return to the streets afterwards. The authorities hope that after their brief recovery they will not want to return to Calais. But it is a fact that migrants often have very fixed ideas about where they intend to settle and it is likely that, after having already endured so much to reach the other side of the Channel, many will continue in their bid to reach Britain where relatives are already settled and where they are more at ease with language. A number of associations offering assistance to the migrants in Calais now report that migrants have begun finding new routes for crossing the Channel, from the nearby port of Dunkerque, and also ports in Belgium and the Netherlands, where small makeshift camps have begun sprouting.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse